In June 2013, the Wall Street Journal asked Republican mega-donor Warren Stephens about the state of small businesses across the nation. The Arkansas banking mogul said they were being squeezed by excessive federal regulation, and singled out one agency in particular: the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

“The stories we hear about that are pretty scary,” the billionaire said.

What went unmentioned: At the time, the same federal watchdog that Stephens was thrashing was investigating the practices of an online payday lender that had been part of his business empire.

Leaked offshore financial records reveal that Stephens had quietly used a set of family trust funds to own a large stake in the parent of the loan company, Integrity Advance, during the time in which the federal agency alleges that the lender ripped off tens of thousands of consumers. The agency says Integrity Advance broke the law by misleading borrowers about the high costs of their loans and aggressively siphoning money out of their bank accounts.

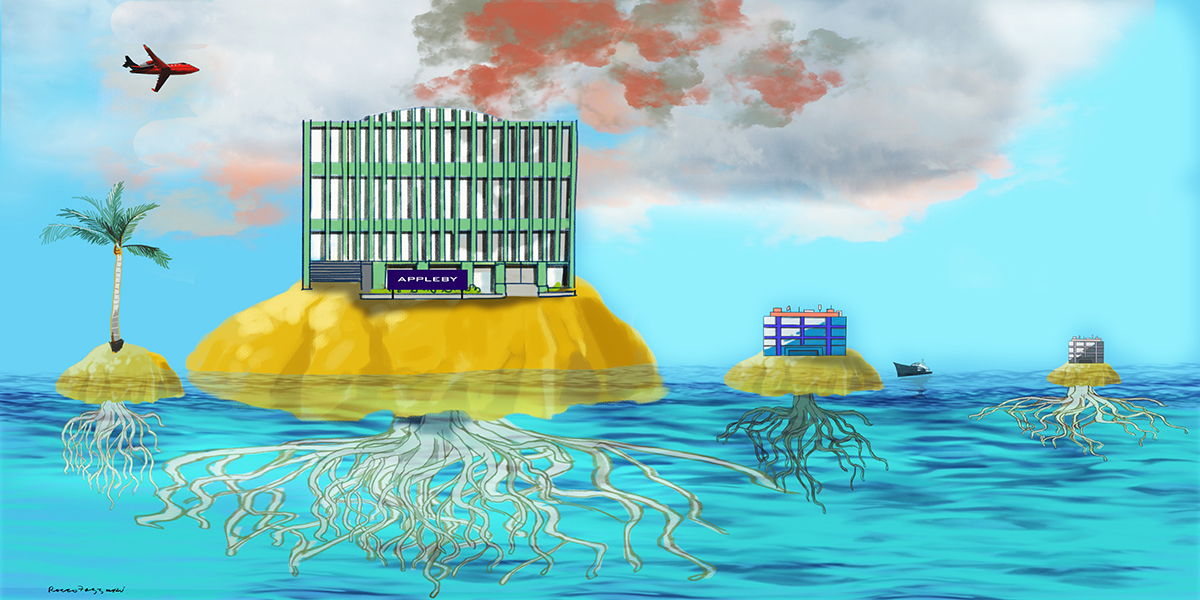

Details of Stephens’ links to the payday lender were uncovered in a joint reporting effort by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and media partners around the world. The reporters drew from a cache of nearly 7 million leaked files from the offshore law firm Appleby and corporate services provider Estera, two businesses that operated together under the Appleby name until Estera became independent in 2016. The records, part of a cache now known as the Paradise Papers, were obtained by German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung.

Through a spokesperson, Stephens declined to provide comment for this story.

Republicans and Democrats

Stephens is one in a constellation of major U.S. political donors connected to offshore holdings that appear in the law firm’s internal files.

This list includes some of President Donald Trump’s foremost donors, who together funneled nearly $60 million to organizations supporting his campaign and transition. They include casino magnate Sheldon Adelson, resort owner Steve Wynn, hedge fund managers Robert Mercer and Paul Singer and private equity investors Tom Barrack, Stephen Schwarzman and Carl Icahn.

Prominent Democratic donors also appear in the law firm’s files.

The documents raise questions about whether Democratic donor Penny Pritzker fully complied with federal ethics rules intended to limit government officials’ participation in matters that could affect their financial holdings. As part of this process, Pritzker pledged to divest her interests in more than 200 firms after she was confirmed as President Barack Obama’s commerce secretary in 2013. The leaked records reviewed by ICIJ show that, in two cases, Pritzker transferred assets to a company owned by her children’s trusts. The documents show the company at the same Chicago mailing address as Pritzker’s investment management firm.

These transfers may not have erased the potential conflicts in question and may have run afoul of federal ethics rules, according to Lawrence Noble, senior director of ethics at the nonprofit and nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center. Public records indicate that one of her children was under 21 when the assets were transferred, meaning the supposedly divested assets may still have been attributable to Pritzker. “Under normal circumstances, if one of the beneficiaries is under 21 and they’re still a dependent child, it doesn’t meet standard of divesting assets,” Noble said.

A spokesperson for Pritzker did not respond to numerous calls and emails asking for comment.

Private equity funds controlled by Democratic mega-donor George Soros used Appleby to help manage a web of offshore entities. One document details the complex ownership structure of a company called S Re Ltd that was involved in reinsurance, or insurance for insurers. The structure, a chart shows, included entities based in the tax havens of Bermuda and the British Virgin Islands.

A spokesperson for Soros — who has donated money to ICIJ and other journalism outlets through his charitable organization, the Open Society Foundations — declined to comment for this story.

The leaked documents’ revelations about the offshore activities of top American political donors underscore concerns about how the global system of tax havens helps the rich and powerful operate in ways that, though often legal, provide advantages not available to average citizens.

In recent years, Warren Stephens has been an increasingly generous political donor. During the last federal election cycle, Stephens gave more than $13 million to conservative groups and candidates, making him the eighth-largest Republican benefactor of the cycle. Stephens opposed Trump in the presidential race, contributing millions to anti-Trump groups.

Stephens also gave to groups that have fought to weaken the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which was created at the urging of the Obama administration in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. During last year’s campaign season, Stephens contributed more than $3 million to the Club for Growth, a conservative advocacy group that has pushed for Congress to strip the CFPB of its rulemaking and enforcement powers. Last year, Stephens was named the campaign finance chair for French Hill, an Arkansas Republican congressman who has been a fierce opponent of the CFPB.

Along with bankrolling political battles in Washington, Stephens has used his investment bank, Stephens Inc., to launch an online video series that seeks to improve millennials’ opinion of free-market economics. The series is intended to inspire viewers to “celebrate capitalism, its inherent social contract, and the good it can do for our society,” according to Stephens. He says his aim is to reverse the growing notion that the free market is “a system that enriches a few at the expense of the many.”

Payday battles

The battle over payday lending began long before Stephens’ under-the-radar involvement in the industry began.

Payday lenders make small loans – often for $500 or less – to borrowers who need money fast. State regulators have accused many payday operators of trapping customers in cycles of overpriced debt. Some payday lenders have tried to sidestep scrutiny from state authorities by enlisting commercial banks and even Native American tribes to act as front organizations for them.

In late 2011, representatives of Stephens and his business partner, James Carnes, contacted Appleby to incorporate two offshore entities for a new venture related to small-dollar lending. The correspondence included documents that detail the pair’s co-ownership of Integrity Advance’s parent company, Hayfield Investment Partners. One of the documents asserts that Stephens had made a “significant investment” in the company in 2008, causing him to own more than a third of Hayfield by 2012.

A separate memo goes on to state that Hayfield’s “main two controllers are Warren Stephens and James Carnes.”

One set of leaked documents shows that Stephens invested in the lending operation primarily through three family trusts, which put more than $13 million into Hayfield. Two investment funds with addresses listed at Stephens Inc.’s headquarters contributed an additional $1.7 million, according to the records.

Documents also show that various Stephens Inc. executives and other acquaintances of Warren Stephens also invested in Hayfield through a company associated with Stephens. These investors included the golf star Phil Mickelson, who chipped in $12,000, according to the documents.

In its legal action against Integrity Advance, the CFPB emphasized Carnes’ 52-percent ownership stake in Hayfield — which derived the bulk of its profits from Integrity Advance — as well as his management of the lender. It appears that neither financial regulators nor the news media have mentioned Stephens’ sizable stake in Hayfield.

Citing pending litigation, a spokesperson for James Carnes declined to comment for this story.

Borrower complaints

As Integrity Advance’s business grew, so did complaints to state regulators from its borrowers across the country. By November 2012, Integrity Advance had received cease-and-desist letters from state regulators in Connecticut, Illinois, Kentucky, Mississippi and South Carolina, according to a federal filing.In May 2013, a Minnesota district court ordered the company to pay nearly $8 million in civil penalties and restitution to victims, asserting that the firm had “targeted some of the State’s most financially vulnerable citizens” with interest rates as high as 1,369 percent.

In ruling against Integrity Advance, the Minnesota court described a process that would become familiar in regulatory filings involving the lender: Borrowers found Integrity Advance online, took out small loans and then would see large withdrawals from their bank accounts for interest and services fees. After several months, such costs alone could far exceed the amount they had originally borrowed.

You’re doing this to people in bad situations, people who can’t afford this to begin with, and you’re taking advantage of them even more?

One borrower, Nils Paul Warren, a broadcast audio technician for NASCAR in Orlando, Florida, complained to the state’s financial regulators that he had been forced to shell out more than $1,300 to repay a short-term $500 online loan he got from Integrity Advance in 2009 — a sum far more than what he had expected or thought legal.

“I think the bulk of their clientele are people who are a paycheck away from being homeless,” Warren told ICIJ in a recent interview.

He recalled asking one Integrity Advance representative: “You’re doing this to people in bad situations, people who can’t afford this to begin with, and you’re taking advantage of them even more?”

Warren said the state never responded to his complaint.

Public records requests that ICIJ submitted to state regulators across the country yielded dozens of consumer complaints about the company’s lending and collections practices.

“I have been devastated by this entire situation and on the verge of eviction because of the illegal fees,” stated a complaint from one Michigan borrower, who alleged that she had been harassed by collectors for Integrity Advance.

“They keep calling me at work,” an Ohio woman wrote in a complaint alleging that she had already paid a total of $956 for a $400 loan. She claimed that collectors for the lender at first “said they were from the FBI.”

Public records show that Integrity Advance responded to the Michigan and Ohio complaints with nearly identical letters categorically denying the allegations and stating that the company “at all times acted properly and in accordance with our contractual commitments and applicable law.”

The Michigan and Ohio letters both stated that “without the obligation to do so” Integrity Advance had “marked her account as ‘paid in full,’ ” with the “understanding that she will not be able to obtain credit from Integrity in the future.”

CFPB steps in

Eventually, Integrity Advance would be pursued nationwide. In January 2013 — just weeks after Stephens and Carnes sold large portions of Hayfield’s assets to a “pawn loan” specialist called EZCORP Inc. — the federal watchdog sent Integrity Advance a letter demanding information about its lending practices.

Such a letter would probably have alarmed any business. This was not a lone, overmatched state regulator. The CFPB represented a new and powerful force in Washington: an agency with nationwide jurisdiction and staffed with attorneys devoted to rooting out abusive practices by financial firms that operate across state lines. The CFPB had been created, in part, because of concerns about the difficulties encountered by state authorities trying to crack down on payday lenders.

Not everyone celebrated the new agency.

In mid-2013, Stephens told an Arkansas business and politics journal that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau was “the most misnamed thing of all time,” adding: “It’s almost like we’re going to deny people credit instead of protect them. We’re going to protect them by not giving them any credit.”

Financial trade groups, enlisting their Republican allies, made the watchdog agency a key target in the push to dismantle the Obama administration’s regulatory legacy. The CFPB has had to defend itself against successive legal challenges based on the assertion that it has no constitutional right to exist. Its court battles have been coupled with attempts to turn public opinion against the agency, with one group running an ad campaign last year that encouraged people to write their members of Congress and urge them to put an end to the CFPB’s “abusive practices.”

During the presidential campaign, Trump pledged to undo provisions of the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reform law, which established the CFPB. With Trump’s ascent to the presidency, the agency’s future has become even more uncertain. In October 2017, the Republican-controlled Senate voted to block a CFPB rule that would have made it easier for customers to join together to sue their banks. The vote was seen as the largest victory so far for banking interests during the Trump administration.

Hayfield and Appleby

Stephens’ standing as a billionaire business leader was not only useful for mounting attacks on the new federal finance watchdog. It also came in handy when pitching Hayfield Investment Partners as a client to Appleby. A confidential business plan that Hayfield apparently sent to Appleby in November 2011 boasts that Stephens Inc. is “recognized as one of the foremost authorities” in the U.S. consumer finance industry.

An internal Appleby memo assessing Hayfield dwells on Stephens’ business successes and points to his estimated $2.8 billion personal fortune, stating that he is the “490th richest man in the world.”

Appleby went on to accept Stephens’ business. In 2012, to verify his identity when registering a new offshore Hayfield subsidiary, Stephens provided Appleby with a scanned copy of his passport, a personal reference and his home electric bill. (Appleby helped incorporate offshore firms that amounted to separate Hayfield subsidiaries, but the firm had no role with Integrity Advance.)

Publicly available evidence of Stephens’ links to Hayfield and Integrity Advance is scarce. One clue was a Stephens Inc. representative’s signature that appeared at the bottom of a December 2012 filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission detailing the sale of Hayfield assets to EZCORP.

In Appleby’s files, Stephens’ name appears repeatedly in language that portrays him, in his capacity as an investor, as an important figure in Hayfield’s business ventures — a detail absent from the public narrative surrounding Integrity Advance. The only place Stephens’ name shows up in CFPB’s public case file is in a deposition in which James Carnes refers to a private equity fund named “Stephens” that he said had held a large stake in Integrity Advance since 2008.

In early 2013, the CFPB formally demanded that Integrity Advance turn over the name of anyone who owned more than 5 percent of the lender. In response, the agency received an chart detailing the names of several of Hayfield’s primary owners. There was one notable exception: Warren Stephens.

Strategy shift

A review of financial documents and sworn statements by Carnes regarding his own earnings suggests that Stephens likely profited handsomely from his investment in Hayfield.

Even in the months preceding its sale, Hayfield was quietly contemplating a shift into a new and controversial trend in the payday industry, according to the Appleby firm’s documents.

In 2011 and 2012, the records show, Hayfield communicated with Appleby about incorporating offshore firms intended to provide consulting services to American Indian tribes interested in becoming online lenders. Appleby arranged for the registration of two companies — Black Oak Consulting in the British Virgin Islands and Rustic Hill Advisors in the Isle of Man. The venture was to set up in a way that would provide confidentiality, which was needed because of the “highly competitive nature of the business that the client is involved with,” one memo said.”

Another Appleby memo stated that the initial client would be the Turtle Mountain Band of the Chippewa Indians, which occupies a reservation in northern North Dakota.

It’s unclear from the records whether Hayfield’s plans to work with the Turtle Mountain Band or other Native American groups became a reality. In response to questions about the offshore consultancies, a spokesman for the Turtle Mountain Band said he was unable to locate any record of its having done business with those entities.

Hayfield and its subsidiary, Integrity Advance, soon had other issues to deal with. In November 2015, the CFPB issued a notice of charges against Integrity Advance and Carnes, alleging a systematic effort to deceive borrowers from the time of the lender’s founding in 2008 until it stopped issuing loans in December of 2012.

In 2016, an administrative law judge issued a ruling recommending that Integrity Advance and Carnes pay more than $50 million in civil penalties and restitution to victims. (Such a recommended decision precedes a final determination of penalties by the CFPB’s director.)

Carnes and Integrity Advance are appealing the decision, arguing that “the findings of fact, conclusions of law, and proposed relief are arbitrary, capricious” and an abuse of discretion.

They are also countersuing the CFPB, alleging that the pursuit of Integrity Advance exceeded the agency’s authority because the payday lender is not covered under the agency’s mandate.

The bureau, the countersuit alleges, is pursuing an “unconstitutional retroactive application of the law.” Echoing the financial industry’s broader attacks on the CFPB, the countersuit claims that Obama’s 2012 recess appointment of the financial watchdog’s director, Richard Cordray, was also unconstitutional.

Citing the pending litigation, the CFPB declined to comment for this story.