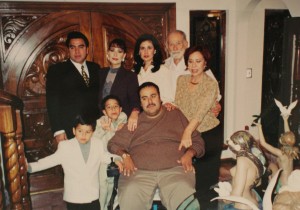

Jorge Abraham sits in his parents’ living room in a single-story rental on a rutted street in El Paso, Texas. His soft, sloping shoulders twitch involuntarily. His head and contorted right hand are the only parts of Abraham’s morbidly obese frame that move by volition — the result of a 1988 motorcycle accident that left him quadriplegic.

Behind him, the living room is stacked nearly to the ceiling with belongings — including three horse saddles — that once decorated Abraham’s former home, an expansive custom-built mansion.

Abraham was the unlikely kingpin of one of America’s biggest ever cigarette smuggling rings — a racket that spanned three continents and six states and moved as many as a half-billion contraband cigarettes across the United States. As lucrative as narcotics, but with far less onerous penalties, tobacco smuggling is booming around the country — and around the world. Abraham, released from federal custody in June, recently talked for the first time publicly about his operation, the cheap, illegal smokes that Americans increasingly crave, and the bungled case against him that led from Chinese counterfeiters and American Indian smoke shops to a chilling Mexican house of death.

“This was an extremely important case,” said John W. Colledge III, former program manager for international tobacco smuggling at U.S. Customs Service. “Very sophisticated… probably one of the two most significant [federal cigarette] cases.”

But Abraham’s case was far from isolated. The trade in illicit tobacco today makes up 11 percent of all tobacco sales, and it has made cigarettes the world’s most widely smuggled legal consumer product, according to the Framework Convention Alliance for Tobacco Control, an initiative under the auspices of the World Health Organization (WHO). The costs of this underground commerce are massive, robbing governments worldwide of an estimated $40 billion to $50 billion annually in tax revenue. The growing trade in contraband cigarettes also helps fuel an addiction estimated to cost America alone more than $167 billion annually in deaths, sickness, and lost productivity, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for 1997-2001. At the same time, the trade has attracted organized crime gangs and even terrorist groups, who find the mild penalties and hefty profits ideal for making money. On October 20 in Geneva, the WHO will bring together 160 nations to strengthen controls against tobacco smuggling, hoping to spark a concerted crackdown against the Jorge Abrahams of the world.

“Must be a doper”

Jorge Abraham was the youngest of three children of a Syrian immigrant father and Mexican mother. As a boy, he performed at rodeos across Mexico and sang in a children’s choir — once sitting on the knee of the popular ranchero singer Vicente Fernández. He dropped out of school after the 11th grade. His parents — Nasser and Gloria — opened first one and then another successful steakhouse in El Paso and across the border in Juarez. Gloria boasts about the clientele, who she said included martial arts action actor Chuck Norris.

Abraham launched an import-export business in Mexico in 1991, supporting his family and himself by importing toys, clothes, and household goods from China into Mexico. He met a woman, fell in love, and married, then built the family a 6-bedroom, 4.5-bath estate complete with elevator and pool in a gated community in nearby Santa Teresa, New Mexico. He bought two properties in Mexico, and opened an import-export business in El Paso.

Abraham’s wife drove a new Jeep Cherokee. His sister drove a new BMW. He had two new handicap-accessible Ford vans at his disposal and a host of bodyguards who traveled with him between Mexico and Texas.

Law enforcement suspected Abraham was smuggling narcotics. But he had a deal that was sweeter than dope.

“When I [would cross the border] . . . I was always surrounded by a lot of people. I attracted a lot of attention,” Abraham said. “The FBI hated that.”

Colledge said it’s a common story. “This is how border law enforcement worked at that time. Mexican-American flashing a lot of wealth — must be a doper.” The FBI conducted surveillance outside Abraham’s warehouse and inspected his trucks before they traveled to Mexico. But they never found drugs, and after a while they stopped coming around, Abraham said.

“So I knew back then they were checking; they kind of had a hard-on for me,” Abraham said. He smiled and shook his head and was quiet. After a moment he snorted and smiled again as he considered his subsequent decision to smuggle cigarettes.

“What the hell was I thinking? Honestly, I didn’t think it was such a big deal.”

Easy money

It started in 2000 with a woman — not his wife, from whom he had separated the year before.

“I was dating this girl, and her sister introduced me to this guy,” Abraham said. “This guy from Juarez — he was kind of young, involved in bringing in cigarettes and crossing them into Mexico.”

Together they bought Marlboros slated for export from warehouses in Miami and El Paso. That part was legitimate. Legally they could export them, paying taxes to the import country. Instead, Abraham and his partner smuggled them into Mexico, bypassing entrance taxes with the help of a Mexican customs agent.

Not long after they started in 2000, the Mexican customs agent was transferred; Abraham was stuck storing thousands of cigarettes in a bonded warehouse in El Paso. His partner said they had to move the cigarettes, or else the product would go stale.

“I was a very well-known businessman in import-export merchandise,” Abraham said. “So I told the customs broker, ‘clear ‘em, because I’m going to cross ‘em.’ And he did.” But then instead of crossing the cigarettes legally into Mexico, Abraham sold them to a buyer in Los Angeles. In doing so, he avoided paying mandatory state and local taxes, instead pocketing the difference. He had invested $200,000 in the 900 cases — 9 million cigarettes — which he shipped through a cargo mail service.

“We doubled our money just like that,” he mused. “I said, ‘This is easy. It’s cigarettes. It’s not a big deal.’ So we started doing it more and more often, until they seized a load.” Although Abraham cannot remember for certain if he and his partner had used fake names to send the untaxed cases, Abraham said he got scared the first time Customs seized his shipment of cigarettes.

“I said, ‘How are they going to react?’ But nothing happened,” Abraham explained. “So then we waited a little bit and did it again.”

Three months into their new business, Abraham and his partner split. Abraham continued sending cigarettes to California while selling other — legal — imports to buyers in New York. During a discussion about sugar with one of those East Coast buyers — who Abraham simply called “the old man” — Abraham mentioned he could supply cheap cigarettes.

“Got any buyers for cigarettes?” Abraham asked.

“Let me find out,” the old man said.

Soon after, another man called Abraham. “So they tell me you can get duty-frees,” the man said, referring to cigarettes slated for export. “Can you send them to New York?”

Abraham said he could, and they decided on an initial small shipment of one master case — 50 cartons. The shipment went smoothly, with the old man acting as intermediary.

“We doubled our money just like that…I thought, ‘This is easy. It’s cigarettes.’”

— Jorge Abraham

And so it began: Jorge fielded orders over the phone, then placed orders of his own for shipments of export-bound cigarettes from wholesalers in El Paso and Miami. He received those shipments at warehouses in El Paso and had them cleared for export. Instead of exporting the cigarettes, however, Jorge sent them in bulk by cargo mail service to buyers in California and New York, destined for the open market. Most in demand: Marlboros, but Newport Menthols were also popular in black communities and Camels in American Indian communities, he recalls.

The Indians became big business for Jorge. He moved truckloads of the tax-free smokes to the Cattaraugus Indian Reservation in western New York state, the largest reservation of the Seneca Nation — a wealthy tribe known for its sweet-grass woven baskets and elaborate corn husk dolls. The rural 2,400-person, 22,000-acre spread bordering Lake Erie was home to Abraham’s biggest buyers, who, along with other “smoke shops,” peddled millions of under-the-table cigarettes to the general public. Through the old man, Abraham’s shipments went to a colorful trio of distributors there, people whom Abraham’s attorney would later describe as “Broadway types.”

There was Scott Snyder, who had served as police marshal and political party chairman on the Cattaraugus Reservation. Snyder lived on the reservation and ran the Iroquois Tobacco Co. out of his home. Donald “Don” Deland was a one-time professional football player (college All-American, a Buffalo Bill, and a Dallas Cowboy) turned discount cigarette salesman. Based out of the reservation, he operated Internet sites such as smokemcheap.com and dutyfreetaxfree.com, promising to sell “the same cigarettes that you are buying at the store for Outrageous Prices at the lowest Tax Free Prices you will find Anywhere!” And then there was Timothy “Tim” Farnham, with a background in marketing, who boasted that he once worked for Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign. Farnham was the moneyman of the three, providing upfront funds.

From the reservation, the contraband cigarettes flooded into New York City, eventually being sold openly by the city’s bodegas and street vendors. So popular were Abraham’s smokes that he became notorious among local smugglers, who referred to him simply as “the guy in the wheelchair.”

Enter “Lalo”

With the New York connection in place, business boomed. But by early 2001, Customs began routinely seizing shipments of Jorge’s untaxed cigarettes. Officials never seemed to know Abraham was behind the shipments, but just for safe measure, he would lay low for a few weeks after a seizure. Then the cargo shipping company transporting Abraham’s cigarettes refused to handle any more. One of the company drivers “had some trouble” from Customs on his way to the Cattaraugus Reservation. Until he found another way to deliver his goods, Abraham felt he had no choice but to stop the deliveries.

Lalo was a mustachioed Mexican from Durango, south of the California border. Jorge had met him through a well-connected figure in Mexican organized crime, and Lalo quickly became instrumental to Abraham, managing shipments and watching over the business. A former cop in Juarez, Lalo was tall and slightly overweight, with drooping eyes and jowls. He spoke with a slight stutter, Abraham recalled.

Lalo mentioned he knew truckers willing to move drugs. Abraham asked him if they would move cigarettes instead. After settling on a price, Abraham’s men loaded a 53-foot truck with contraband cigarettes and stacked the final 10 feet with boxes of toilet paper. (Later he would use jalapeños — a heavier product, and thus less likely to be moved during routine searches at Customs checkpoints.) Lalo and one of the drivers he had solicited took the loads to New York. They arrived without a glitch.

“They got all excited,” Abraham said. Even before the truckloads arrived, his New York distributors had a line of customers ready to buy. “If I would have sent them 10 containers a week, that wouldn’t be enough.”

Business was great for a while — Abraham was making shipments two or three times a week, each worth about $400,000. He opened off-shore bank accounts to store the cash. But seizures picked up, and soon, Abraham said, they couldn’t get anything through.

When Abraham told Snyder, Deland, and Farnham that they had to stop for a while, the buyers balked. So Abraham tried buying contraband cigarettes from Switzerland. But those shipments were seized, too.

By then, a dozen people in El Paso were helping Abraham buy and ship contraband cigarettes. Five people in California and a half-dozen in New York bought Abraham’s products, reselling the cigarettes in smoke shops and on Internet sites. Abraham says he knew one of them was “a rat.” He never suspected it might be his stuttering sidekick, Lalo.

A house of death

Lalo is the reason Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials have refused to discuss this case. A dozen calls and e-mails to ICE public affairs have gone unanswered, not only because of Lalo’s work as an informant, say former officials with knowledge of the case, but also because of his ties to a murderous Mexican gang and a house out of a horror flick.

When Customs sought approval to tap Abraham’s phones in July 2002, they relied solely on information gleaned from Lalo’s work. It was Lalo who introduced an undercover agent as the drug-smuggling truck driver, who informed Customs agents of Abraham’s shipments, and who recorded his phone calls and meetings with Abraham. For his services, Lalo received almost $225,000 over four years.

In February 2003, Lalo began working on a high-profile case for Customs and the DEA involving Heriberto Santillan-Tabares, one of the leaders of the murderous Vicente Carrillo Fuentes Cartel, which controls billion-dollar drug routes from Mexico into the United States. The syndicate, also known as the Juarez Cartel, was among the hemisphere’s most powerful criminal organizations in the 1990s, responsible for as much as half of all drugs that entered the United States from Mexico. While its power has diminished with the suspicious death of leader Amado Carrillo Fuentes in 1997, the organization is still considered one of Mexico’s four most powerful cartels, with operatives in two-thirds of Mexican states. Lalo was deeply enmeshed, so he made the perfect mole.

That summer Lalo was arrested near Las Cruces, New Mexico, with 100 pounds of marijuana hidden in the tires of his Chevy pickup. The DEA dropped Lalo as an informant, said then-DEA Special Agent in Charge Sandalio Gonzalez. But ICE kept him on the payroll — even after news arrived of the grisly events at Calle Parsioneros 3633.

The house at Calle Parsioneros 3633 in Juarez is a hodgepodge middle-class cinderblock home near the city’s industrial center. In August, Lalo was at the house where — allegedly on Santillan’s order — he supervised the murder of a Mexican drug trafficker named Fernando Reyes. They tried strangling him with an electric cord, but it broke. So they slipped a plastic bag over his head and, after a few minutes, whacked him on the head with a shovel just for good measure. Lalo recorded the events and took the evidence that evening to his handler at ICE, which was trying to build a case against Santillan, according to court records. News of the murder reached ICE headquarters in D.C. by that night. The next day the agency’s El Paso office received orders from headquarters to continue the Santillan investigation with Lalo as informant.

Yet the murders at Calle Parsioneros continued. Between August 2003 and January 2004, 11 more people were brutally slain at Calle Parsioneros 3633 — some or all of them allegedly on Santillan’s order and under Lalo’s supervision.

“This situation is so bizarre that even as I’m writing to you, it is difficult for me to believe it,” Gonzalez wrote. “I have never before come across such callous behavior by fellow law enforcement officers.”

Three days after Gonzalez sent his February 2004 letter (and long before Santillan was even arrested) ICE would scramble to wrap up their case against Abraham, who still had no idea that Lalo was the rat.

A move to counterfeits

“At the beginning I never had any trouble with him,” Abraham said of Lalo. “But after a while, you know, something inside me said, ‘Something is wrong with this guy.’”

One day while visiting friends at a local tire shop, Abraham said he spotted Lalo driving down from Sunland Park Drive — a road leading from a cluster of federal law enforcement offices — wearing a dress shirt and tie.

“I was inside my van and I said, ‘Is that Lalo?’ Every time I would see him it was boots and jeans and a shirt, just like that,” Abraham said, motioning with his right hand to his own T-shirt. He couldn’t figure out why the Mexican man speaking limited English would be driving away from that section of El Paso. Jorge had one of his young employees dial Lalo’s number.

“Hey, turn back,” Abraham said into the receiver. “I just saw you. Turn back. I’m at the tire store.”

Lalo complied. But when he climbed from his car, Lalo was wearing a sweater.

“Are you hot?” Abraham asked. “It’s kind of hot to have a sweater on.”

Lalo’s face turned a shade of pink, and he mumbled something about being cold.

“Well, take your sweater off,” Abraham ordered. Lalo complied. He wore a dress shirt beneath the sweater, but had removed the tie. Abraham suffered a moment of suspicion. But Lalo seemed too well-connected to be an informant.

From the reservation, Abraham’s cigarettes flooded into New York, to be sold by the city’s bodegas and street vendors.

Abraham, meanwhile, was growing increasingly concerned about the number of shipments being seized. In 2002, he decided to stop trafficking contraband cigarettes altogether. His buyers were frantic, but he felt he had no other choice. One of his West Coast contacts — Giashian “Mike” Lin, a Taiwanese national living in California — then suggested he import counterfeits from China, Abraham recalls. Offered a sample, Abraham was surprised at the quality. The cigarettes appeared authentic. Only when the cigarette was lit, did one realize it was counterfeit — it burned unevenly.

“So I started seeing who was interested,” Abraham said. “Everybody was interested.”

The first containers arrived at the port of Newark, New Jersey, hidden among plastic kitchenware, teapots, and toys. The loads were stashed at Snyder’s home on the Cattaraugus Indian Reservation. Abraham sold his counterfeit Marlboros to the same buyers as his duty-free smokes — in New York, California, and Kentucky.

“At that time the Chinese were so happy,” Abraham said. “They wanted to move 10 to 20 containers a week.” Twenty containers hold 200 million cigarettes. By then, China had emerged as the world’s primary source of counterfeit cigarettes, and Abraham was a good client. So the Chinese suppliers sent California businessman Dean Miller to meet with Abraham in El Paso.

Miller launched Megafood, a successful chain of food stores, in 1987, but the firm ran into financial troubles and went bankrupt in 1994. Miller was sued for fraud in 1997 by a company that loaned him money to keep his failing business afloat. Slapped with a $2.3 million judgment in 1998, Miller filed for personal bankruptcy in 2000. He now wanted to be Abraham’s sole California buyer, exclusively supplying counterfeit Marlboros to West Coast consumers.

Abraham and Miller struck a deal, and Miller agreed to travel to China with a carton each of Marlboro regulars and Lights, so the counterfeiters could update the barcodes on the cartons — because, Abraham explained, Marlboro had started updating the codes every few months to combat counterfeiting. Abraham started ordering regular shipments from China of Marlboro “Reds” and “Whites.”

Abraham’s cell wasn’t the only one importing counterfeits from China. By 2002, bogus Chinese cigarettes were pouring into the United States, attracting a rogue’s gallery of distributors — Chinese smugglers and Russian mobsters joined in, along with Abraham’s Mexican-American gang. There was even a ring of Orthodox Jewish smugglers. Abraham’s New York buyers — Deland, Snyder, and Farnham — were also moving contraband cigarettes from Simon and Michael Moshel, a pair of pious Jewish brothers from New York City. The Moshels started out selling fruits and vegetables when they immigrated to the United States from Israel. After selling their produce business, they launched a plastic bag manufacturing plant, and then, among other ventures, began importing goods such as jeans, counterfeit batteries, and fake Marlboros.

Although tobacco smuggling may seem tame compared to drug trafficking, it is a tough racket, and Jorge could play hard. When Farnham, the moneyman of the New York buyers, owed him $500,000, Abraham stopped shipments, sent his father to settle the account, and called Lalo. “My dad, they leave tomorrow at 6 in the morning to go see that [expletive],” Abraham told Lalo, in a February 2003 conversation recorded by law enforcement agents. “We definitely need to pick him up and take from him whatever we can get from him. . . . And then take him down.”

“Then fix him up?” Lalo asked.

“See how much they want,” Abraham said. “If we can do it this week, let’s do it this week,” quite a bit later adding, “Yes, whack him, because if not, the other guys are going to say, ‘Oh, he . . .’”

Abraham left the sentence unfinished. Abraham didn’t pursue a hit man to carry out the murder, and his attorney said Abraham never seriously entertained the idea.

Around the same time, Abraham sent Miller to Buffalo, New York; containers had arrived at the port in Newark and been transported to a warehouse in Buffalo for dispersal. Miller was to arrange shipment for some of the containers to his warehouse in California. Abraham felt something was wrong, that law enforcement was watching. He suggested they stop shipments for a bit.

“The Chinese didn’t want to stop. Deland didn’t want to stop. Dean Miller didn’t want to stop,” Abraham said. “So I brought in 10 more. But those last shipments, people started complaining they wanted a rebate [because of poor quality]. I had a sample at home. So I told one of the guys to smoke it.” The filter was half the regular size, and people were burning their fingers.

“So I stopped,” Abraham said.

As a federal informant, even after supervising multiple murders, Lalo received almost $225,000.

Meanwhile, Miller told Deland and Snyder that he could bring in containers without Abraham’s help. But what no one knew was exactly how Abraham got his shipments past customs. When he tried on his own, one of Miller’s shipments was seized in California. Another was seized in Newark. During the second seizure, Deland and Snyder were arrested.

Abraham’s Chinese contacts urged him to continue ordering shipments in spite of the arrests and his concerns. Smuggler Mike Lin flew in to talk to him. So did another California-based smuggler, Jeffrey Liu. Abraham’s direct contact in China called, trying to convince him to continue the business.

“The Chinese lady would call me almost every day from China, which I didn’t understand jack [expletive] because she hardly spoke any English,” Abraham said, laughing.

Abraham brought in four more containers, but felt law enforcement closing in. His subsequent decision was perhaps not logical, and he smiles today when he considers it.

“I decided, ‘I’m going to see how close they are.’” Abraham said. “So I started moving duty-frees again. They started seizing everything. Nothing, nothing was getting through. I was losing money more and more, containers and containers.” Over time, Customs seized 20 containers of contraband cigarettes, costing Abraham $8 million.

Abraham had ordered his buyers, movers, and sellers to call him from disposable pre-paid phones, and gave them a number for a disposable phone he had purchased.

“Did they listen? No.” Abraham said. “They would call me back from their houses. . . . I guess they didn’t see how bad it was going to be.”

Thank you letter

The noose finally tightened around Abraham’s ring in February 2004. In a SWAT team sweep by ICE and local police, authorities arrested Abraham, his father, and a dozen other men. Because the local jail lacked the proper medical facilities, Jorge spent the next six months in a hospital bed, watching TV and making friends with the U.S. marshals who acted as guards. Abraham faced 92 counts of trafficking in counterfeit cigarettes, as well as wire and mail fraud — enough charges to put him away for 300 years. Abraham initially asked the court to release him pending trial. “They denied my bond, and said I was a flight risk and I was going to leave. And I probably would have,” Abraham said with a grin. “If they had given me a bond, I probably would have left, but then I only got five years. I’m glad they didn’t [give me bond]. I should have written them a thank you letter.”

The real thanks should have gone to Lalo, who by then was about to be exposed in the sordid, high-profile drama at the drug cartel safe house in Juarez. Tainted by the murders, he was no longer a credible witness against Abraham. Unwilling to put Lalo on the stand, prosecutors agreed to settle short of trial. Abraham pleaded guilty in April 2005 to a single count of conspiracy to smuggle cigarettes into the United States and was sentenced to five years in prison. He agreed, along with his father, to pay nearly $6 million in restitution — a seemingly insurmountable sum to the retired restaurateur now in his seventies and his quadriplegic now-unemployed son.

Abraham’s New York distributors — Snyder, Deland , and Farnham — were each sentenced to between 18 and 27 months in prison. Snyder is currently serving again as chairman of the Seneca Nation’s sole political party, while his father hopes to regain the tribe’s presidency. Abraham’s California connection, Dean Miller, received four years and was ordered to pay a $10,000 fine. Abraham’s father was sentenced to 3 years in prison. His wife faithfully visited every week.

Lalo’s fate remains unknown. Seemingly overnight, the former Mexican cop went from a prized informant to an undesirable illegal alien. Lalo claimed in court that ICE had promised him a green card in exchange for his work and said he feared he would be murdered by the far-reaching Juarez Cartel as soon as he returned to Mexico. But Lalo never got the promise of a green card in writing, and ICE swiftly placed him into expedited deportation proceedings. His plea for asylum is still pending in federal court while he remains in a deportation center at an undisclosed location.

Jorge Abraham was formally released from prison in June 2008 — having completed his final months on house arrest. Even before he was officially free, the telephone started to ring. Old friends wanted to know if he was back in business, he explained with a chuckle and a shake of his head.

On a recent Wednesday evening back in El Paso, he sat at his mother’s dining room table. His father Nasser stood beside Abraham’s wheelchair offering steaming spoonfuls of homemade chicken soup to his son. His mother Gloria bustled, roasting corn tortillas over the open burner. The kitchen smelled of jalapeños and cilantro. A string of telephone calls repeatedly broke the calm. Nasser or a young Latino man held the phone to Abraham’s ear, who told each caller to ring again in 15 minutes.

Abraham plans, he said, to start another business someday, importing goods from China to Mexico.