On May 15, 2014, the prime minister of Iceland stood before parliament answering questions about how aggressively his government would sniff out tax cheats and fraudsters who use secret offshore companies. Would Iceland follow Germany’s lead by purchasing revealing data from offshore whistleblowers?

The prime minister, Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, hedged.

It was “extremely important that people work together on this,” he agreed. But whether obtaining the information would be “realistic and useful” was unclear, he said, adding that he trusted the tax officials to make the right decision.

What wasn’t known was that the offshore files Iceland was considering buying included offshore companies linked to him and at least two other top members of his ruling government.

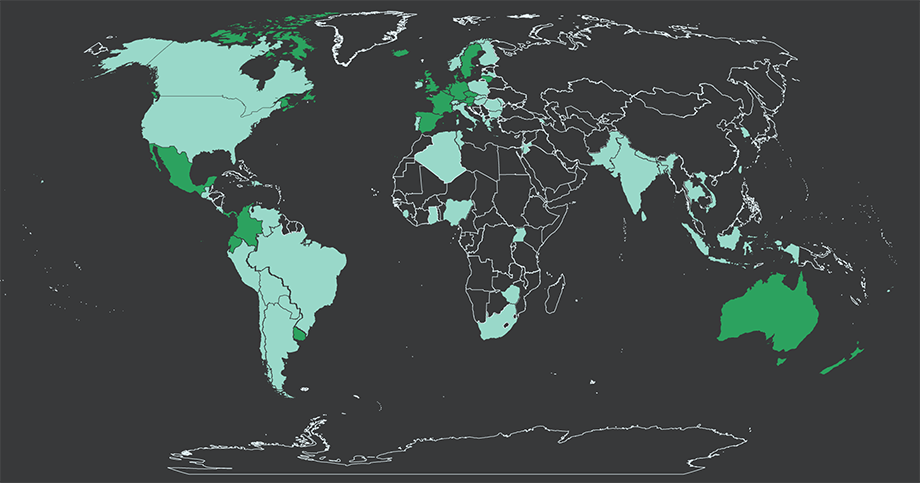

These findings emerge from millions of secret files obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and other media partners. More than 11 million documents — emails, cash transfers and company incorporation details from 1977 to December 2015 — show the inner workings of the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, one of the largest shell-company registration agents in the offshore world. The files reveal confidential information about 214,488 entities registered for individuals and companies in more than 200 countries and territories—including a company created in the British Virgin Islands in 2007 called Wintris Inc.

Gunnlaugsson’s offshore saga

Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson rose to power on a wave of anti-bank anger in the aftermath of the Icelandic financial crisis, which saw the country’s three major banks fail spectacularly over a few days in October 2008 following years of speculation and self-dealing. A journalist and radio-TV personality — he finished third in a sexiest man in Iceland contest in 2004 — an outspoken Gunnlaugsson led a group called InDefence after the crash that campaigned for Iceland to reject bailing out international creditors on billions of dollars in deposits in the banks. In two national referenda, voters sided with InDefence, and the successful campaign helped bring Gunnlaugsson and his party to power.

In January 2009 the Progressive Party elected Gunnlaugsson, a nationalist who once went on an Icelandic-only diet, its chairman to put a fresh young face on a party with roots in Iceland’s agrarian past. At age 38, he would become the youngest prime minister in the country’s history in 2013, promising to play hardball with foreign creditors, offer debt relief to struggling homeowners and end austerity programs. As prime minister, Gunnlaugsson’s government reached an agreement with creditors in 2015 that his old group InDefence criticized as too generous.

The Mossack Fonseca documents show Gunnlaugsson’s family – unbeknownst to Icelanders – had a big personal stake in the outcome for bank creditors.

In December 2007, Gunnlaugsson and his wife, Anna Sigurlaug Pálsdóttir, purchased Wintris Inc. from Mossack Fonseca through the Luxembourg branch of Landsbanki, one of Iceland’s three big banks. The couple used the shell company to invest millions of dollars in inherited money, according to a document signed in 2015 by the prime minister’s wife, the daughter of a wealthy Icelandic Toyota dealer, after she was asked by Mossack Fonseca where she had gotten the money.

“The Icelandic banks formed branches, for example, in Luxembourg and the UK, and what they did there was create offshore companies for their clients to park all sorts of assets,” said Rob Jonatansson, a Reykjavik attorney who led the resolution of a smaller bank that also collapsed, not commenting on Wintris specifically. “The offshore companies afforded the opportunity for tax evasion, which probably some took.”

The Mossack Fonseca files don’t disclose where Wintris invested its money, but court records show that Wintris had significant investments in the bonds of each of the three major Icelandic banks. Those records list the company as a creditor with millions of dollars in claims in the banks’ bankruptcies.

Landsbanki’s winding-up board listed Wintris as a creditor in November 2009 with a claim of 174 million krona — apparently in Landsbanki bonds. Wintris also appeared three times on the bank Kaupthing’s claims list in January 2010, holding bonds with a face value of 221 million krona. And it held Glitnir bonds worth 114 million krona — a claim Wintris sold to an Icelandic investor after the crash, according to a person familiar with the claim (Gunnlaugsson has criticized foreign funds buying up such claims as “vultures”). In all, Wintris claimed nearly $4 million in assets in the banks at current exchange rates and $8 million at pre-crash exchange rates. And Wintris may have held other assets, such as stock, that don’t show up in bankruptcy filings of the banks.

Gunnlaugsson co-owned Wintris with his wife when he entered parliament in April 2009 and has continued to hide it from view as he ascended to the prime minister’s seat, according to the files obtained by ICIJ. Failing to disclose these assets violated Iceland’s ethics rules. The prime minister denies that, saying only companies with “commercial activity” have to be reported. But the parliament’s secretary general says all companies must be disclosed. Wintris’s bonds still have considerable worth, ranging from roughly 15 percent to 30 percent of their face value.

On the last day of 2009, Gunnlaugsson sold his half of Wintris to his wife for one dollar, according to the Mossack Fonseca documents.

On March 15, 2016, Pálsdóttir wrote a Facebook post disclosing the offshore company to the public for the first time. “The presence of the company has never been a secret,” she said. Pálsdóttir wrote that she set up Wintris in 2007 when it was still unclear whether the couple would be living overseas and that it is an investment vehicle for funds she received when her family’s business was sold.

The Facebook post came four days after ICIJ partners Reykjavik Media and SVT (Swedish public television) asked the prime minister about Wintris in a videotaped interview. In that interview, SVT asked Gunnlaugsson if he had ever owned an offshore company.

“Myself? No. Well, the Icelandic companies I have worked with had connections with offshore companies, even the — what’s it called? The worker’s unions. So it would have been through such arrangements, but I have always given all of my assets and that of my family up for taxes. So there has never been any, any of me, my assets hidden anywhere. It’s an unusual question for an Icelandic politician to get. It’s almost like being accused of something, but I can confirm I have never hidden any of my assets.”

When asked what he knew about Wintris, Gunnlaugson said, “Well, It’s a company — if I recall correctly — which is associated with one of the companies that I was on the board of and it had an account, which as I’ve mentioned, has been on the tax account since it was established. So now I’m starting to feel a bit strange about these questions because it’s like you are accusing me of something when you are asking me about a company that has been on my tax return.”

Shortly thereafter, Gunnlaugsson stood up and walked out of the interview.

In Palsdottir’s Facebook post four days later, she said that the assets in Wintris Inc. were hers alone and that a bank’s mistake had led to Gunnlaugsson’s being listed as a co-owner. When the mistake was discovered in 2009, she became sole owner of the company, she said. The Mossack Fonseca documents show Gunnlaugsson signed the document selling his share of Wintris to Palsdottir.

Pálsdóttir said that the assets came from her share of the sale of her family’s business. She said she had always paid all taxes owed on Wintris. Her tax firm, KPMG, also said she declared income from Wintris.

“As has been explained publicly, in establishing this company, the Prime Minister and his wife have adhered to Icelandic law, including declaring all assets, securities and income in Icelandic tax returns since 2008,” a Gunnlaugsson spokesman said in a statement.

It is unclear whether Gunnlaugsson’s political positions benefited or hurt the value of the bonds. The question “is really a tricky one,” said Þórólfur Matthíasson, an economist at the University of Iceland. “Nobody but the PM himself can answer that question.”

Gunnlaugsson’s spokesman said, “In recent years, Prime Minister Gunnlaugsson’s work in politics has been characterized primarily by his determination to ensure, to the extent possible, that the interests of the people of Iceland took priority over the interests of the failed banks’ claimants. Both his words and all of his conduct confirm this.”

Political elites play offshore

The documents also raise questions about the financial activities of other Icelandic political elites and whether they benefitted from some of the same practices of business executives that so outraged their constituents.

“I have not had any assets in tax havens or anything like that,” Iceland’s Minister of Finance and Economic Affairs Bjarni Benediktsson, who is also a top political ally of Prime Minister Gunnlaugsson, said in an interview televised in February 2015.

But Benediktsson — along with two Icelandic businessmen — owned and shared what is known as “power of attorney” over a shell company called Falson & Co. created in 2005 by Mossack Fonseca in the Seychelles, an island chain and notorious secrecy haven in the Indian Ocean, according to the offshore documents. Power of attorney means the three men had the power to approve transactions by the company.

Falson & Co. issued bearer shares, stock instruments that give ownership of an asset to whoever has the physical share certificate. Because bearer shares aren’t registered in anyone’s name, they provide an extra layer of secrecy and have been outlawed in many countries because they’re widely used for fraud and tax evasion. Falson was used as a shell company until it was removed from the company registry in the Seychelles in 2012, according to Mossack Fonseca documents. Benediktsson did not disclose his ownership of the company to parliament or to the public.

Asked about Falson by ICIJ and its media partner Süddeutsche Zeitung, Benediktsson confirmed that he had owned one-third of Falson, which he said was created to hold four apartments in a building under construction in Dubai. “A holding company is a matter of convenience so that all matters are handled by one legal entity. The asset was sold before delivery of the apartment as the owners of Falson & Co decided to back out in 2008 and the asset was eventually sold with a loss. My part in owning this asset has been public information for years.”

The Dubai real estate was reported in 2010 by Icelandic newspaper DV after it obtained emails about the investment.

“I had no intention or need to hide ownership,” Benediktsson said. “I declared my ownership of the company to the tax authorities in Iceland.” Asked why he didn’t declare his stake in Falson to parliament, Benediktsson said, “The (disclosure) rules were implemented in May 2009. At the time I neither owned an active business or a declarable real estate.”

Benediktsson later provided a letter to ICIJ, however, from one of his partners in Falson, that said the company’s business was not wound up until September 2009. Benediktsson said the company was not active after it canceled the purchase agreement in November 2008. “From that time Falson & Co. was not in control of the property,” he said. “Until a new owner was found Falson & Co.’s only purpose was to wait for refunding.”

As for the interview last year where he denied having assets in tax havens, Benediktsson said, “I have to admit that I was not aware of the fact that the company was listed in the Seychelles which would qualify as a tax haven, contrary to Luxembourg. My understanding was that it was a Luxembourg company.”

Another member of the current government, Ólöf Nordal, the interior minister, also controlled a secret company created in the British Virgin Islands in November 2006, according to the documents. Like Wintris and Falson, Dooley Securities SA was purchased from Mossack Fonseca through a Luxembourg subsidiary of Landsbanki, then the second biggest Icelandic bank. Nordal had power of attorney over Dooley Securities with her husband, Tomas Mar Sigurdsson, now chief operating officer of American aluminum giant Alcoa’s Global Primary Products unit, according to the documents, and shares in the company were held in the name of Landsbanki Luxembourg. In August 2007, Sigurdsson pledged Dooley Securities’ shares in an agreement with Landsbanki, apparently as collateral for a loan from the bank, which would collapse a little more than a year later.

Asked by ICIJ about Dooley Securities, Sigurdsson said Landsbanki advised him to create the company to hold the proceeds from a potential sale of his Alcoa stock options. “This never happened, I never exercised the option and I never transferred any funds to the company,” he said, adding that he was not aware of the pledge agreement.

“To be clear, neither I nor my wife, were at this time, nor at any time later, owners of the shares in Dooley Securities,” Sigurdsson said. “We do not own and have never owned any off-shore companies.”

The documents further show that Hrólfur Ölvisson, the executive director of Gunnlaugsson’s Progressive Party and a top adviser to the prime minister, is associated with two companies in the data: Selco Finance Ltd. and Chamile Marketing SA. In 2005, before his party chairmanship, Ölvisson passed control of Selco Finance to Finnur Ingólfsson, himself a former Progressive Party official who helped lead the purchase of Kaupthing when it was privatized.

Ölvisson said the companies were created to market insurance and other products in Iceland. “Everything connected to me has been legal,” Ölvisson said, adding that the companies hadn’t operated for years. “I had accountants and everything regarding that. There is no problem.”

Ingólfsson said Selco was purchased by an insurance company he led and that “the acquisition in no way related to tax benefits.”

The Viking raiders

Iceland was a financial backwater until relatively recently. The country had no stock market until 1985, and its stodgy major banks were owned by the state. It made big moves to liberalize its economy in the 1990s, aiming to “increase economic efficiency by eliminating the distortions inherent in state-ownership.” The government sold its banks to the private sector in the late 1990s and early 2000s and an influx of foreign capital spurred an epic expansion by the country’s financial industry. By 2008, the assets of the three major banks, Kaupthing, Landsbanki, and Glitnir had ballooned to $180 billion — 11 times the size of the national economy, in one of the greatest financial bubbles in history.

News media lauded Iceland’s business and financial titans as the New Viking Raiders. The country’s economic elite snapped up billions of dollars of foreign businesses and flew in artists like Elton John and 50 Cent for private parties. Fishermen became investment bankers. Iceland’s stock market soared 800 percent from 2001 to 2007.

Then it all fell apart over three days in October 2008.

Iceland’s big three banks collapsed, sending the country’s economy into a depression. The stock market collapsed 97 percent from its peak. The value of the Iceland’s currency — the krona — fell by half.

Iceland nationalized the big banks and defaulted on deposits from foreign investors, causing diplomatic brawls with the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Thousands protested in front of parliament, pelting the building with rocks and fireworks, and eventually helping to bring down the government. Parliament indicted then-prime minister, Geir Haarde, for negligence in office, and in a largely symbolic move, a court convicted him of failing to inform his cabinet of major events in the crisis.

Amid the chaos, it became clear that many of Iceland’s top bankers had lent money to their cronies through offshore companies and manipulated the market to make the banks look healthier than they really were.

Bank insiders did so by lending tens of billions of krona (hundreds of millions of dollars) to each other, the banks’ owners and favored associates, allowing them to load up on shares in the Icelandic banks with no risk to themselves. This duped investors and regulators into thinking there was real demand in the markets for Icelandic banking shares. In some cases, insiders simply looted the banks, having the bank lend vast sums of money to themselves and their friends to buy stock and then having the bank buy back their shares at more than market value when the banks ran into trouble.

Untangling the ties

Iceland, alone among Western governments, has vigorously prosecuted its top bankers, sending at least two dozen to prison. Four of the top seven Icelandic bank officials, as well as each of the top shareholders of the three big banks, controlled offshore companies registered through Mossack Fonseca. But the dealings were so complicated, thanks to the help of Mossack Fonseca and others, that wrongdoing and reparations are still being sorted out more than seven years after the crash. Some of it may never be uncovered.

“Most definitely something is going under the radar,” Olafur Hauksson, who led Office of the Special Prosecutor created after the crash, said in an interview before the information obtained by ICIJ and Süddeutsche Zeitung was revealed. Hauksson was the brawny police chief of Akranes, a fishing village of 6,600, when he became special prosecutor. He was the only Icelander who wanted the job.

Despite his successes in putting key players in jail, Hauksson said the secrecy enabled by the offshore industry means there are things he has missed.

“You see companies maybe from the Caymans or Tortola or something like that, banks that have a subsidiary in Luxembourg but that (are) actually stationed in Iceland,” Hauksson said. “This gives you a very hard time to see the whole picture of the events. You have fractures in three places, and putting it all together is a huge effort, and it requires that you have a cooperation in various fields and knowledge to know what to seek.”

Indebted to the banks

The documents obtained by ICIJ detail the wider role of Mossack Fonseca in a global secrecy machine that helps the rich and the powerful hide their business dealings and hang on to more of their money, which results in other taxpayers paying more tax. They also shed light on the cozy ties among elites on this wet, windswept island of 329,000 people.

“Iceland is so small, and we know the person, and we know the family of the person,” says Vilhálmur Bjarnason, a member of parliament and an academic who was one of the first to warn about the fast-and-loose practices of the country’s banks.

The timing of some of the future Prime Minister’s activities coincides with those of companies controlled by controversial Icelandic businessmen.

Wintris and two other unrelated bearer-share companies controlled by Icelanders each opened separate bank accounts at Credit Suisse in London on the same day in March 2008, the documents show. The three companies each had the same nominee directors — straw men provided by Mossack Fonseca to rubber stamp decisions while obscuring the true identities of the owners. All three companies — Wintris, Jarl Universal SA and Jade Trading Services Ltd— were purchased and administered through the Luxembourg subsidiary of Landsbanki.

Jade Trading and Jarl Universal are not run-of-the-mill companies. They were controlled or associated with powerful Landsbanki players who have been investigated — though not charged — in the market-manipulation scandals that roiled Iceland.

Jade Trading Services was controlled from 2004 to November 2007 by Landsbanki chairman Björgólfur Guðmundsson and Andri Sveinsson, who works for Guðmundsson’s son, Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson, the richest man in Iceland.

In January 2008, Jade Trading issued power of attorney to Sigurdur Bollason, an Icelandic investor who used other companies to secure $144 million in collateral-free loans from Landsbanki, Kaupthing, and Glitnir during the summer of 2008 to buy shares in the two banks. Bollason was later named as a co-defendant in a class action suit and was a target of raids by Hauksson’s Office of the Special Prosecutor in Luxembourg regarding the market-manipulation scandal. Bollason has not been charged.

Jarl Universal, meanwhile, was also controlled by Bollason and linked with other companies he controlled, including one that sent a $622,000 dividend to the Landsbanki Luxembourg account of another of his shell companies four days before Landsbanki was seized by the government.

Even with the information revealed by the Mossack Fonseca files, it’s still unclear exactly what was going on with these companies. While the Panamanian law firm is a key link in the chain of secrecy used in the Icelandic banking schemes, it’s only one link. Getting the full picture would require a look inside the banks, investment advisers and other law firms connected to the shell companies.

“Some of the cases have been so complex you actually don’t get through to see what’s actually in there,” says Hauksson, the special prosecutor. “Who is the real person behind this? And that is going to be the battle between the investigators and the ones that want to have the money hidden.”

Iceland’s tax authority did end up purchasing from whistleblowers a small portion of the documents relating to Mossack Fonseca in the hope of finding tax evaders and recovering lost revenue. The documents purchased include information about Wintris, the shell company now owned solely by Gunnlaugsson’s wife.

To date, authorities have said nothing publicly about what they’ve learned.