She spun a story the world wanted to believe: a self-made billionaire who had risen in a male-dominated business world in an African country ravaged by civil war and poverty.

In public appearances in the spring of 2017, Isabel dos Santos, then head of Angola’s giant state oil company, Sonangol Group, mingled with Hollywood legends on the French Riviera and charmed oil tycoons in Houston with tales of hard work and accomplishment. Wearing her trademark black blazer at the London Business School, the 44-year-old chairwoman told a packed audience that leaders should be chosen on their merits.

“I’ve been managing companies for a long time, starting them from small, building them up, going through every single stage of what it takes for a company to be successful,” she said.

Left unmentioned in London: That she had been installed in the top job at Sonangol by her father, José Eduardo dos Santos, the longtime Angolan autocrat. That over the years he had awarded her companies public contracts, tax breaks, telecom licenses and diamond-mining rights. And that even as she spoke to the crowd of aspiring entrepreneurs, she was paving the way for one of her most brazen insider deals — the payment of tens of millions of dollars from the state oil monopoly to a company in Dubai controlled by her business partner.

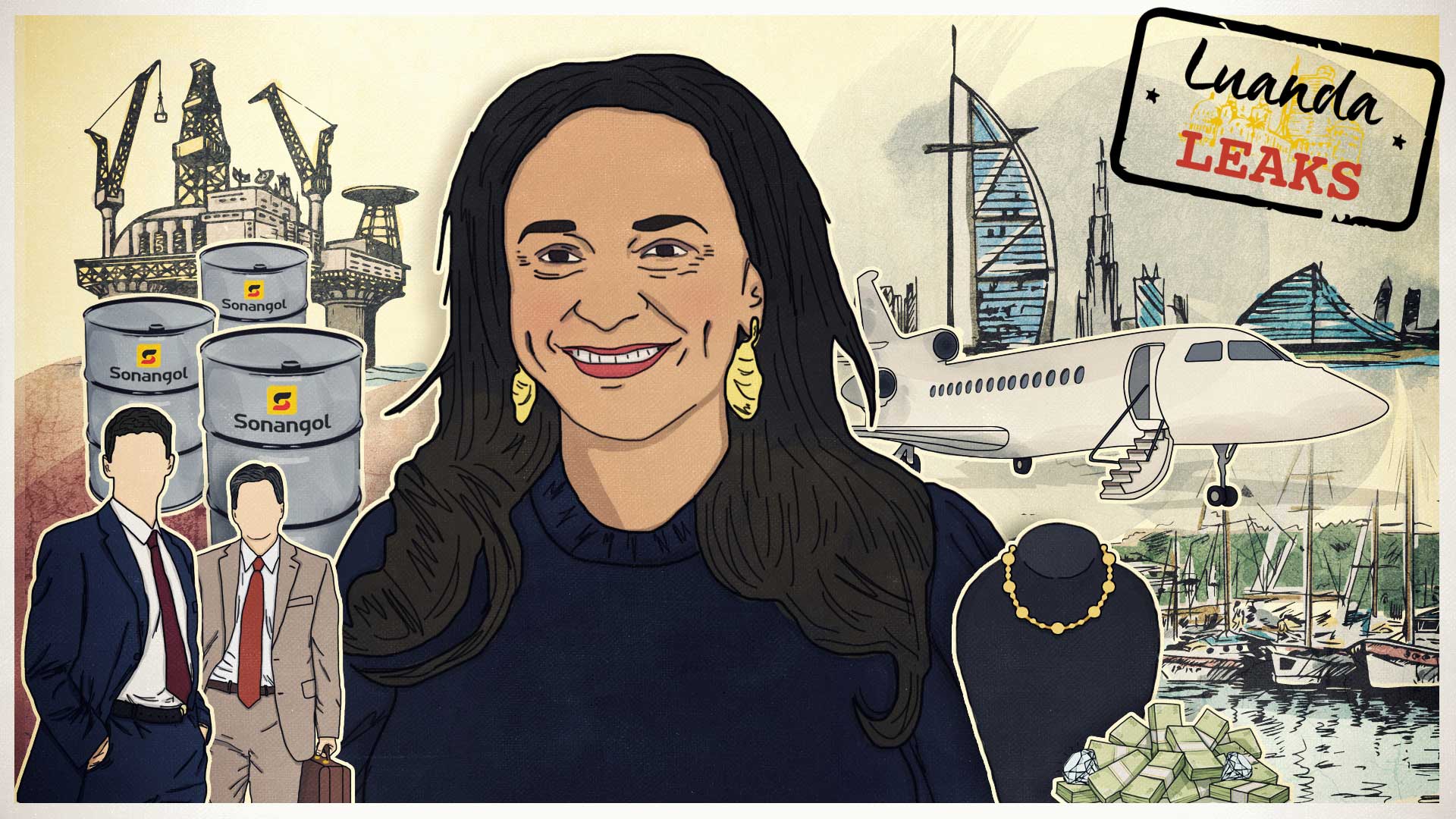

Luanda Leaks, a new investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and 36 media partners, exposes two decades of unscrupulous deals that made dos Santos Africa’s wealthiest woman and left oil- and diamond-rich Angola one of the poorest countries on Earth.

Based on more than 715,000 confidential financial and business records and hundreds of interviews, Luanda Leaks offers a case study of a growing global problem: Thieving rulers, often called kleptocrats, and their family members and associates are moving ill-gotten public money to offshore secrecy jurisdictions, often with the help of prominent Western firms. From there, the money is used to buy up properties, businesses and other valuable assets, or it is simply hidden away, safe from tax authorities and criminal investigators.

“The movement of dirty money through shell companies into the international financial system to be laundered, recycled, and deployed for political influence is accelerating,” said Larry Diamond, a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. “It heightens the danger of political violence and human rights abuses.”

Public corruption drags down economies, erodes faith in democracy and diverts money that could otherwise be spent on hospitals, schools and roads. Transparency International rates Angola as one of the most corrupt countries in the world. The average life expectancy is just 60. About 5% of infants die before their first birthday.

The Luanda Leaks documents were provided to ICIJ by the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa, or PPLAAF, a Paris-based advocacy group. The trove contains emails, internal memos from dos Santos companies, contracts, consultant reports, tax returns, private audits and videos of business meetings. The documents, in Portuguese and English, date back to 1980, but mostly cover the last decade. They include descriptions of palatial homes in Lisbon and Monaco and a deluxe vacation featuring private aircraft and a speedboat. Emails show underlings fretting about risky bank loans and financial advisers fielding dos Santos’ requests to pay a bill from luxury fashion designer Valentino and open a new bank account offshore.

ICIJ found that dos Santos, her husband and their intermediaries built a business empire with more than 400 companies and subsidiaries in 41 countries, including at least 94 in secrecy jurisdictions like Malta, Mauritius and Hong Kong. Over the past decade, these companies got consulting jobs, loans, public works contracts and licenses worth billions of dollars from the Angolan government.

Dos Santos and her husband used their archipelago of shell companies to avoid scrutiny and invest in real estate, energy and media businesses. Documents also show businesses linked to the couple steering consulting fees, loans and contracts to shell companies they control in the British Virgin Islands, the Netherlands and Malta.

In one case identified by ICIJ, thousands of families were forcibly evicted from their Luanda homes on land that was part of a redevelopment project involving a dos Santos company.

They also secured large stakes in banks, allowing them to finance this empire even as other financial institutions backed away amid concerns about dos Santos’ ties to the Angolan state.

The family’s worsening reputation didn’t spook brand-name accountants and consultants, which continued to work for dos Santos-linked businesses, ICIJ found. Big companies and state-backed entities from China and the Netherlands continued to partner with the family’s private businesses.

Angolan government officials told ICIJ that they are investigating whether dos Santos and associates looted hundreds of millions of dollars from the state’s oil and diamond-trading companies. That includes a $38 million payment in November 2017 from Sonangol to a company in Dubai controlled by a dos Santos associate, a transfer ordered hours after Angola’s new president fired her from her job as head of the state oil company.

The officials also said that public contracts awarded by her father’s regime to her companies were inflated by more than $1 billion.

In December, two weeks after ICIJ questioned Angola’s government about dos Santos’ business dealings, an Angolan court froze her major assets, including banks, a telecom company and a brewery. The government is trying to recover $1.1 billion that it says is owed by dos Santos, her husband and a close associate of the couple.

Through their U.S. lawyers, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, dos Santos and her husband denied wrongdoing and said they did not profit from political connections.

Carter-Ruck, a UK law firm representing Isabel dos Santos, said the businesswoman denied all wrongdoing, including any allegations of looting, fraud, contract overcharging and other misconduct.

The law firm said in a 10-page response that dos Santos didn’t use offshore vehicles to avoid paying taxes. She denied any of her companies evicted people. Dos Santos and the owner of the Dubai consulting company said the Dubai payments were for legitimate services provided to the state oil company.

In recent interviews, dos Santos, whose fortune is estimated at about $2 billion, said the government is on a “witch hunt” against her family. She denied that contracts were steered to her or that she was shown favoritism when her father was president.

Shortly after the asset freeze, she posted a reassuring message on Twitter for her followers and employees. She condemned the government’s move as politically motivated.

Dos Santos declined ICIJ’s requests for an interview. In an interview with BBC News, which asked several questions on behalf of ICIJ, dos Santos called the inquiry a “political persecution.”

“My holdings are commercial,” she said. “There are no proceeds from contracts or public contracts, or money that has been deviated from public funds.”

Her husband, Sindika Dokolo, told Radio France Internationale, one of ICIJ’s partners in France, that the Angolan government is wrongfully targeting him and his wife.

“They want to blame us for all the corruption and bankruptcy in Angola,” Dokolo said. “We pay taxes in Europe, and we’re Angola’s biggest tax contributor. We’ve worked and invested a lot in this country, more than many others.”

Dos Santos’ father and Angola’s former president, José Eduardo, didn’t respond to ICIJ’s requests for comment.

A daughter of ‘Comrade Number One’

Isabel dos Santos, age 46, was born in an Azerbaijan oil town, Baku, where her parents met while attending a state university devoted to oil and chemistry.

Her Russian mother, Tatiana Kukanova, was studying geology. Her father — the future Angolan president and “Comrade Number One” — was then an exiled guerilla leader in the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (known by its Portuguese acronym MPLA).

In 1975, the Portuguese colony became one of the last in Africa to gain independence. José Eduardo dos Santos returned home with his wife and infant daughter. Kukanova went to work at Sonangol, the newly formed and fast-growing national oil company. A former executive recalls seeing Isabel at the office sitting on her mother’s lap.

José Eduardo quickly rose through the ranks of the now-ruling MPLA.

The death of Angola’s first president, Agostinho Neto, propelled the former guerilla fighter to power in 1979. With a brutal civil war dividing Angola José Eduardo moved swiftly to cement control, placing friends in key posts. He acquired near-dictatorial powers, including over Sonangol.

The oil company would become a pillar of the regime and the Angolan economy, accounting for more than 90 percent of total export revenue. Oil paid for everything — roads, bridges, food imports and the military.

The marriage to Kukanova didn’t last. In 1978, dos Santos fathered a son, José Filomeno, in a separate relationship. The following year, Kukanova moved with her daughter to London. Isabel spent her teens attending an elite prep school and went on to King’s College London, where she received an engineering degree. Her financial managers, the leaked documents show, later referred to her as “The Engineer.”

In 1992, President dos Santos changed the Angolan constitution to say the president could not be prosecuted for any official actions “except in the event of bribery or treason to the motherland.” The new language opened the way for him to give public assets to family and friends. Dos Santos treated Angola “like his personal farm,” Salvador Freire, a leading human rights lawyer in Luanda, told ICIJ.

His eldest daughter was a prime beneficiary.

In 1999, the president set up the Angola Selling Corp. with an exclusive license to market Angolan diamonds, another pillar of the country’s economy.

He gave a separate company — controlled by Isabel dos Santos and her mother — a 24.5% share in Angola Selling Corp.

A year later, the dos Santos government issued a hugely valuable mobile telecommunications license, one of the country’s first, to a company called Unitel. Among its owners and founders: Isabel dos Santos.

“Our proposal was one of the most daring and aggressive ones,” she told the BBC.

Lisbon bonanza

In December 2002, hundreds of guests crowded into a 17th-century Luanda cathedral to witness the wedding of Isabel, then 29, to Sindika Dokolo, age 30, a wealthy Congolese businessman and art collector. With a passion for Porsches, American professional basketball and African art, the outgoing Dokolo would become a key business partner to his wife and her champion. She is a “general on the battlefield,” he said in a 2017 interview.

By her early 30s, dos Santos owned luxury apartments in London and Lisbon worth millions. She had a taste for things Western: art shows in Miami, Dolce & Gabbana fashions, weekends in Paris. And she remained close to her father. At family gatherings, the two would sometimes pull out guitars and jam together. In a TV interview years later, she said that from her first day at school, when her father held her hand and gave her courage, he remained a “great source of inspiration.”

Her father’s connections opened doors to one of her most important business relationships: Portuguese billionaire Américo Amorim.

Amorim had started in his family’s cork business before expanding into energy, real estate and banks.

With an oil boom creating demand for new financial institutions, Amorim and the president’s daughter teamed up to launch Banco BIC SA in 2005. It is now one of the largest banks in Angola, with $4.2 billion in assets. The partners subsequently moved into cement, real estate and energy.

To manage their growing empire, Isabel dos Santos and her husband set up an operational base in central Lisbon on posh Avenida da Liberdade above a Louis Vuitton flagship store. Mario Filipe Moreira Leite da Silva, an accountant formerly with the Big Four firm PwC, joined their financial management firm, Fidequity, and took charge of their finances.

Silva, named one of the country’s most powerful people by a Portuguese news channel, would become a key adviser and troubleshooter for the couple and a director at more than a dozen of their companies.

For legal work, she turned to Jorge Brito Pereira, a prominent legal scholar who at the time was a partner with the powerhouse Lisbon-based law firm PLMJ.

In 2005, Amorim and Sonangol closed a deal that would give the couple a valuable stake in an energy company at a bargain-basement price. It was their first major international deal.

The Portuguese billionaire and Sonangol formed an investment firm, Amorim Energia BV, which then bought a third of Portugal’s high-flying energy company, Galp Energia.

The idea for the deal came from Isabel dos Santos, her husband told Radio France Internationale. “The goal was to work on the whole [oil supply] chain from production to pumps, including the refineries,” Dokolo said. “Sonangol had neither the connections nor the skills to put together such an ambitious business plan.”

The Amorim-Sonangol joint venture named Dokolo to its board. Dos Santos had “significant influence” on the company, according to a confidential report on her holdings prepared by her financial advisers.

A year later, Sonangol sold 40% of its stake in the joint venture to Dokolo’s Swiss company, Exem Holding AG. The purchase price was $99 million, but Sonangol agreed to lend Exem most of the money needed to complete the sale, receiving just $15 million up front.

In the interview with the BBC, dos Santos said the deal benefited all sides. “This investment generated a large amount of return for all the parties that invested jointly,” she said. ”There are no wrongdoings.”

Dokolo told ICIJ that the loan was fully repaid in 2017. Sonangol said it rejected the repayment offered in Angolan currency as a violation of the deal. It considers the balance outstanding.

Sonangol didn’t explain why it agreed to sell the stake in the lucrative joint-venture to the then-president’s son-in-law.

Today the stake is worth about $800 million.

Shell games

Isabel dos Santos’ fortune was growing. Her advisers looked for ways to protect it.

In 2009, her business empire had expanded to include stakes in Portuguese banks and media companies, which provided her with millions of dollars in dividends.

She renovated her $2.5 million duplex penthouse in Lisbon. One invoice reviewed by ICIJ showed $50,000 spent on curtains, $9,200 on chaise lounges and nearly $7,500 on gym equipment from Harrods. Six years later, she bought a second apartment on one of the same floors for $2.3 million, though local land registry records don’t indicate if the two units were merged into one.

Over the coming decade, the dos Santos team would set up shell companies in many tax havens but quickly settled on a favorite: Malta.

The tiny Mediterranean nation, now embroiled in a political crisis over the 2017 car-bomb murder of an investigative journalist, is notorious for lax enforcement of laws against money laundering. Its officials rarely ask questions about the origin of foreign cash deposits or follow up on allegations of corruption or illicit money flows, according to a recent International Monetary Fund report.

Among the documents in the Luanda Leaks is a 16-page guide on the tax advantages of Malta, written by dos Santos’ lawyers at PLMJ. The 2015 pitch explained how, by incorporating a company in Malta, a client can start a business and collect dividends, interest and royalties without paying any withholding taxes.

The dos Santos team hired PwC’s Malta office to audit company accounts.

PLMJ and PwC declined to comment on services they provided to dos Santos companies.

The team also engaged an all-star local crew, including a former chief executive of the Malta Financial Services Authority and a former member of Parliament, to serve as directors for dos Santos shell companies.

Dos Santos and her husband used a Maltese shell company, Athol Limited, to buy a $55 million apartment in Monte Carlo, documents show. The 7,600-square-foot property was on the sixth floor of a luxurious complex named La Petite Afrique overlooking the Mediterranean Sea.

In 2010, Dokolo incorporated two Malta companies to acquire a controlling stake in a struggling Swiss luxury jeweler called de Grisogono. His business partner in the deal was Angola’s diamond-trading agency, Sodiam, which co-owned the Maltese entities.

Dokolo’s idea was to create a company that would control Angola’s diamond industry from mining to polishing to retail, he told ICIJ through his lawyers.

Sodiam helped finance the acquisition and loaned the jewelry company more than $120 million total, records show. Dokolo — who invested his own funds in the jewelry company — had “full control of the management,” according to a draft shareholder agreement in the leaked documents.

In the interview with RFI, Dokolo said the use of offshore jurisdictions was a business necessity. “It is very difficult for someone from Angola or the [Democratic Republic of the Congo], which are countries completely blacklisted on European markets, to open a bank account on European soil,” he said. “If you are like me, a politically exposed person since 2001, it is almost impossible. I can be criticized for using financial vehicles located in tax havens, but is that illegal?”

The couple claimed through lawyers to have received no tax benefits through their offshore companies.

The couple’s empire of shell companies grew steadily. By March 2013, they had created or invested in at least 94 companies in 19 countries. A third of these were shell companies.

That month, Isabel dos Santos was named to Forbes’ World’s Billionaires List.

Among the people listed, she was the youngest from Africa and Africa’s only woman.

Ambition and eviction

By the time she was 40, dos Santos had accumulated major shareholdings in media, banking, energy, retail and more.

She owned 25% of Unitel, the mobile phone company that had turned into a cash machine. From 2006 to 2015, it would pay out more than $5 billion in dividends to shareholders, ICIJ calculated.

She owned stakes in two Portuguese banks, Banco BIC and Banco BPI, a communications group called ZON Multimédia and its affiliate, ZAP, a satellite TV service.

She controlled Angola’s biggest cement producer, Nova Cimangola. She was preparing to launch Candando, a supermarket chain, and Sodiba, a beverage company that distributed an Angolan beer called Luandina.

Dos Santos was now a leading economic force in Angola; her companies employed thousands. In Luanda, shoppers would soon carry Candando bags, watch ZAP TV and sip Luandina lager. Orange-trimmed Unitel stores were everywhere.

She presented herself as a public-spirited, self-made success.

In 2013, soon after she was named a billionaire, she told the Financial Times that her entrepreneurial spirit dated back to age 6, when she started her first business, selling chicken eggs to support her cotton candy habit.

“I’m someone who wakes up in the morning, very early, goes out to the field, puts on the boots,” dos Santos recently told the BBC. “I build stuff, if necessary. If I need to carry boxes with my staff, and we need to put it on the shelves, I’ll be putting it on the shelves in my supermarkets.”

In Luanda, her hometown, dos Santos had been amassing buildings and other property for years and working on her next big venture: a massive urban-renewal project.

In later interviews, dos Santos said she no longer recognized the city of her childhood and wanted to uplift it. The civil war had forced millions of people from the land-mine-strewn countryside to urban areas. Shantytowns were everywhere.

Dos Santos said she wanted a Luanda of wide boulevards, green open spaces and a sweeping coastline studded with high-rise apartments.

“What we really want to see is people living in African cities to go from living in dwellings to living in homes,” she said.

Remaking a city would require outside help.

In early 2013, representatives of her real estate and construction-management firm, Urbinveste, began meeting with executives of Dutch giant Van Oord Dredging & Marine Contractors BV, according to confidential emails and other documents.

The Dutch and Angolan partners discussed a dredging and construction job that would include artificial islands, a new beach, a fishery port and a coastal road. She would later say the plan involved “highly specialized dredging and land reclamation” and “no need to evict or relocate any residents or any communities.” The project would be done on “100% reclaimed land from the sea.”

The cost would total $1.3 billion.

Maps from Luanda Leaks show that the plan cut through a vibrant 50-year-old fishing community and some of the best beaches in Luanda. Home to some 3,000 families, its name was Areia Branca, Portuguese for “White Sands.”

On May 10th, the concept was pitched to the president himself, according to a report by the local development agency. Different developers had drawn up other plans for the area as recently as 2009.

The consortium led by dos Santos’ company got the go-ahead.

Before dawn on a Saturday in June 2013, soldiers, police and members of the presidential guard moved into Areia Branca. Residents were evicted, and bulldozers set to work demolishing houses, according to complaints and letters compiled by Luanda-based nonprofit SOS Habitat. The neighborhood was leveled.

“There was nothing; no warning, no notice, nothing,” recalled Talitha Miguel, a 41-year-old schoolteacher, in an interview with Trouw, ICIJ’s Dutch media partner. “It was as if it were a massacre.”

Reputation under fire

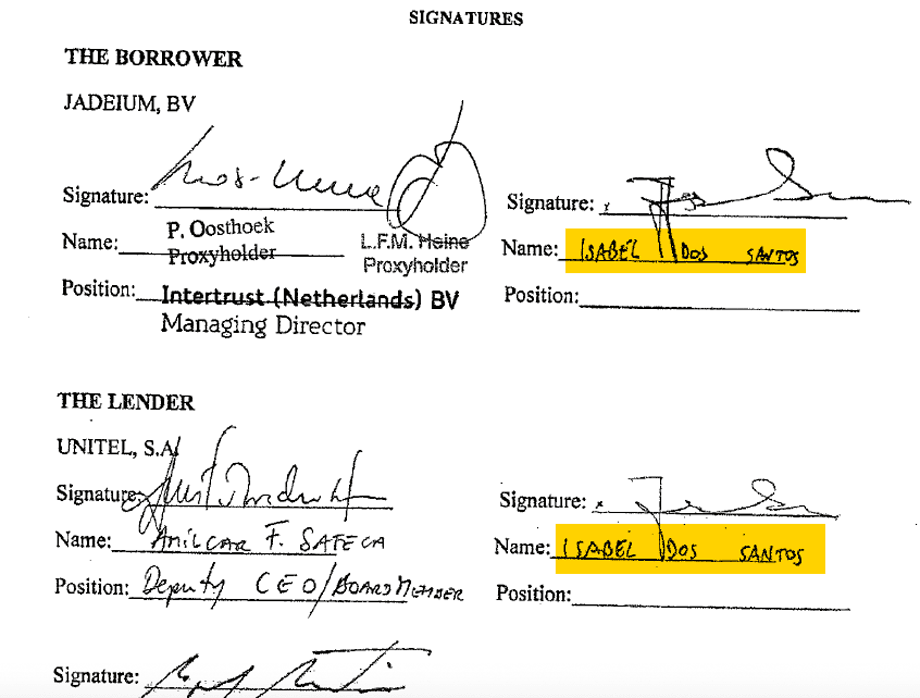

On June 12, 2013, less than two weeks after the Areia Branca evictions, dos Santos faced a question about a massive transfer of money. Unitel had made $460 million in loans the previous year to a Dutch shell company called Unitel International Holdings, later revealed to be owned by dos Santos.

Luis Pacheco de Melo, a representative of PT Ventures, one of four partners in Unitel, asked at a shareholders meeting whether the board of directors had signed off on the deal.

Dos Santos assured him that the loans were properly approved, according to board meeting minutes.

De Melo wasn’t the only one asking about the family’s finances.

An agent in charge of registering Mauritius companies for dos Santos’ telecom business found information about her “source of wealth” missing from the documents.

A $1.3 million transfer from the Maltese holding company that controlled the Swiss jeweler to a Dokolo shell in the British Virgin Islands baffled a Swiss accountant. Auditors for the Maltese company couldn’t find agreements for millions of dollars in loans from the Angolan government to the jewelry company.

On the Isle of Man, John Murphy, a local director for a shell company used to acquire London real estate, discovered a mysterious $50 million credit on its bank statement. “It cause[s] us serious concern,” Murphy said in an August 2015 email to a dos Santos attorney.

He resigned soon after.

And, the documents show, Western banks started to back away. Regulators globally had been cracking down on financial institutions that didn’t carefully vet public officials and those connected to them. Banks and financial regulators consider these clients, known as “politically exposed persons,” or PEPs, as money laundering risks.

In 2012, Citigroup Global Markets Limited abruptly abandoned an investment deal linked to dos Santos; the banking giant later paid $15 million as part of a confidential settlement. Barclays Bank bailed on a similar deal a year later. Both banks were responding to concerns about the company’s shareholders, including Sonangol and Exem Energy, documents show.

Emails show that the dos Santos financial team struggled to find banks to handle her growing business.

“I’m a bit concerned on the Deutsche,” wrote Konema Mwenenge, one of Dokolo’s closest advisers, referring to Deutsche Bank. “Sindika had accounts with Deutsche in the past and [they] were closed. They also blocked some of his payments when they acted as correspondent banks for several beneficiaries.”

Dutch trust company Intertrust and ING bank closed accounts of dos Santos and Dokolo-linked companies that invested in Galp.

One dos Santos business manager told another in an email that one bank had said Dutch authorities were scrutinizing her companies and imposing “extremely complex diligence” requirements.

One dos Santos executive complained to another that Spanish banking giant Banco Santander “ran like the devil from the cross” because of her status as a politically exposed person.

In September 2013, dos Santos’ reputation took a big public hit. In an article written by Kerry A. Dolan, a staff writer, and Rafael Marques, a journalist and activist, Forbes magazine reported that dos Santos had exploited her status as Angola’s first daughter on her way to amassing a fortune that the magazine then put at $3 billion.

“As best as we can trace,” the story said, “every major Angolan investment held by Dos Santos stems either from taking a chunk of a company that wants to do business in the country or from a stroke of the president’s pen that cut her into the action.”

To counter bad news, dos Santos hired Portugal’s best-known public relations consultant, Luis Paixão Martins and his firm, LPM Communication, which specialized in what it called “online reputation management,” “storyselling” and “media coaching.”

PR operatives touted dos Santos’ business and philanthropic achievements. Dos Santos granted interviews and began to appear on panels at high-profile corporate events.

In 2015, she opened an Instagram account that would soon become her online calling card and now reaches 187,000 followers with snippets of news and homespun wisdom. That July, she posted about her latest business, a shopping mall set to open in a Luanda suburb, and said it would create 600 new jobs. She added:

“Work 😀 and build…this is how dreams are realized 😉👍.”

Banks back away

As dos Santos sought to repair her reputation, the dispute with the dissident Unitel shareholder flared into the open.

PT Ventures filed an arbitration complaint with the International Chamber of Commerce in Paris, alleging that Unitel’s Angolan shareholders had wrongly withheld board seats and dividends. It also alleged that hundreds of millions in loans made to the dos Santos Dutch shell company were part of a “scheme to loot Unitel of its assets … for the benefit of Isabel dos Santos, the daughter of Angola’s President.”

Luanda Leaks documents show dos Santos signed off on the disputed loans as both borrower and the lender.

Unitel couldn’t show proof that its board had approved the loans. Dos Santos’ company denied the looting allegations and said all decisions were made in “the best interests of Unitel.”

Increasingly excluded from the mainstream Western financial world, the dos Santos empire needed capital. Defiant, dos Santos blamed anti-African bias and vowed to build “a true African network” of banks as an alternative.

“Africa has been cut out from financial institutions,” dos Santos told business students in London in 2017. “There’s a lot of discrimination,” she said. “We have taken upon ourselves to build these banks.”

She increasingly leaned on her African network, including Banco BIC Cabo Verde. The bank, which she part-owned, helped her businesses move huge sums – and saw profits skyrocket. From 2013 to 2017, the bank turned a 1.7 million euro ($2.3 million) loss into a 12.9 million euro ($15.5 million) profit, according to ICIJ partner Finance Uncovered.

In Europe, dos Santos relied on the last bank that remained friendly to her businesses: Banco BIC Portugues (now EuroBic), in which she owned nearly half of the shares.

The bank’s then-chairman, Fernando Teles, was a dos Santos business partner.

When dos Santos’ husband inquired about an $11.9 million loan for his de Grisogono jewelry business, Mario Silva, the couple’s business manager, confirmed that the financing would be provided. He said Teles could greenlight more bank loans. Teles did not respond to requests for comment.

Eventually, Banco BIC, too, came under government scrutiny.

In 2015, Portuguese central bank regulators had begun investigating allegations of self-dealing along with hundreds of “high-risk’’ transactions at Banco BIC, some involving dos Santos, according to a confidential central bank report, obtained by ICIJ’s Portuguese partner Expresso.

The regulators probed lax anti-money-laundering procedures, inadequate due diligence on politically exposed people — including dos Santos, her husband and her mother — and the preferential $11.9 million loan to Dokolo for de Grisogono.

They found that the bank had failed to monitor multimillion-dollar transfers out of Angola to European-based companies linked to dos Santos, her husband and associates.

“The bank’s internal control system is INEXISTENT,” the report concluded.

Neither dos Santos nor anyone else was ever charged with wrongdoing. In a statement to ICIJ, a spokesman for the central bank, Banco de Portugal, said regulators ordered Banco BIC to tighten procedures.

In a recent interview with a Portuguese news organization, dos Santos criticized media coverage of the bank inquiry and said she was a victim of “sensationalism.”

“There’s nothing in the report that mentions me,” she said.

From crisis, an opportunity

The 2014 collapse of world oil prices sparked Angola’s biggest economic crisis in decades. As the months dragged on, trash piled up in the streets of Luanda. Public hospitals ran out of syringes and antimalarial drugs. Women gave birth by cell phone flashlight.

Angola had used oil as collateral for loans from China to build roads and dams. Now it could no longer pay its debts, and Beijing wasn’t happy. Neither were Chevron, ExxonMobil and Total, which were also owed hundreds of millions of dollars.

In the past, Sonangol had come to the rescue. But costs at Angola’s state oil monopoly had ballooned during the flush years. Now it was going broke.

Amid the bad news, dos Santos companies found opportunity.

On Sept. 16, 2015, nothing less than the future of Sonangol was on the agenda at a meeting Isabel dos Santos attended that included Alexandre Gorito, a Luanda-based senior partner at U.S. consulting giant Boston Consulting Group.

Boston Consulting, hired by dos Santos advisers, pitched a 52-page plan to rescue the state oil company. Working with the Lisbon-based law firm Vieira de Almeida, Boston Consulting would seek to amend government rules and laws as part of a restructuring to increase Sonangol’s efficiency, Luanda Leaks documents show.

The plan included a leading role for a Maltese company, Wise Intelligence Solutions. Its only shareholders were dos Santos and her husband.

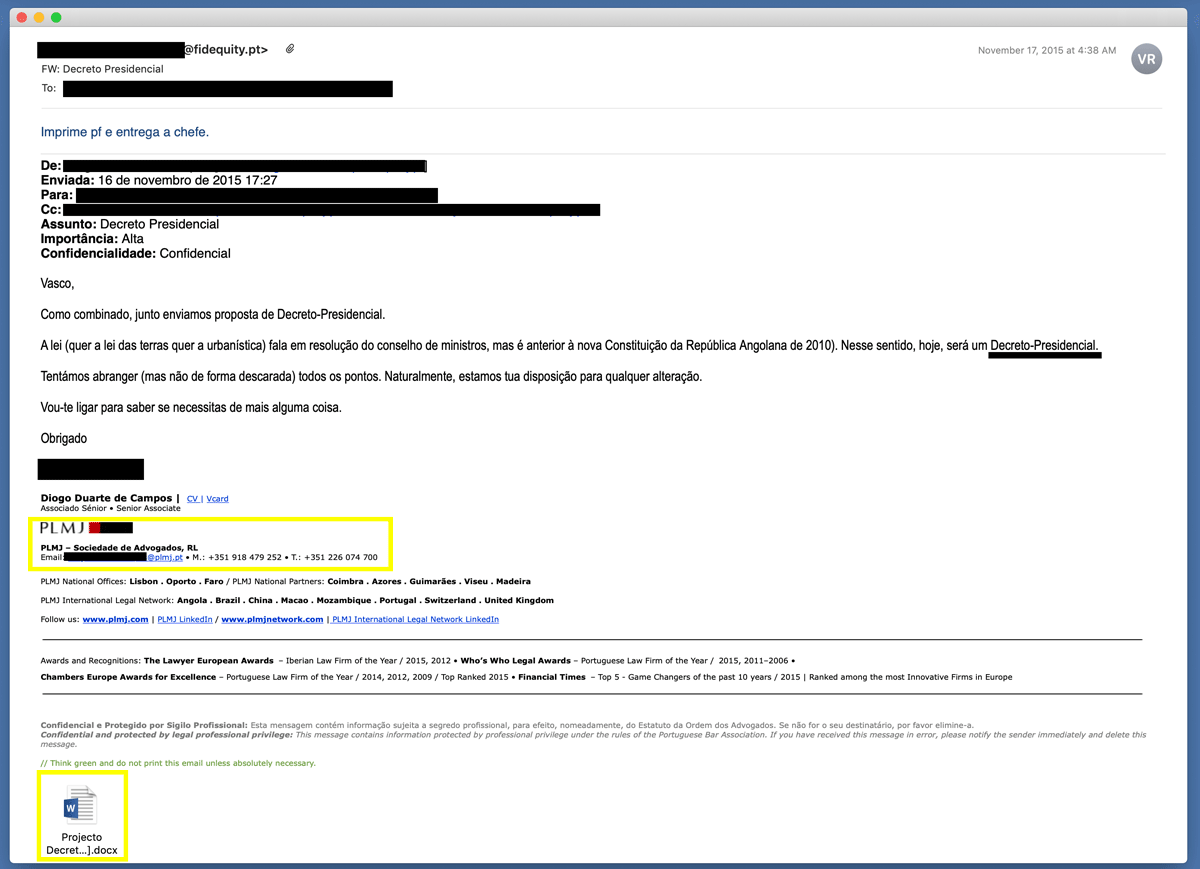

The consultants and lawyers also revised a draft presidential decree creating a special government commission to oversee the Sonangol overhaul.

One month later, President dos Santos issued the decree forming the special commission. The Ministry of Finance gave Wise a $9.3 million contract to advise the panel. Wise wouldn’t work alone. One of the company’s accountants told dos Santos’ financial advisors in an email he believed Wise did “not have the human resources and specific know-how” to deliver without subcontractors.

Wise would go on to hire Boston Consulting, along with PwC.

Dos Santos later said the Angolan government asked for her help because she had international private-sector experience. The Western firms she brought in, she said, were “advisers that had worked with me in the past and that I trusted.”

Under the contract, Boston Consulting would propose a new operating model for the oil company.

Boston Consulting received $3.7 million from Wise, the leaked records show. PwC was paid $273,000 and Vieira de Almeida lawyers at least $490,000. It’s unclear how much Wise kept.

Vieira de Almeida spokeswoman Matilde Horta e Costa told ICIJ that the law firm “takes its client intake and risk management procedures very seriously” and never advised dos Santos as an individual client.

Boston Consulting spokeswoman Nidhi Sinha told The New York Times, an ICIJ partner, that in Angola the firm “reviewed the payment structures and contracts … to ensure compliance with established policies and avoid corruption and other risks.”

Grand vision

After 35 years in power, President dos Santos signaled that he would soon step down.

The global oil slump and ensuing economic free fall had led to a spiral of public protests, government repression and violence.

With retirement looming, the president made bold moves that would benefit his daughter.

His administration awarded an array of public works contracts, saying it hoped to boost employment and put money in the pockets of Angolans.

ICIJ’s reporting shows, however, that some of the main beneficiaries were Isabel dos Santos’ businesses or the large or politically connected firms and banks operating with her.

In October 2015, the president officially authorized the redevelopment project he had approved one month before the Areia Branca evictions. The green light came in a presidential decree that, ICIJ documents show, his daughter’s lawyers in Portugal had helped to draft.

For the road work, documents sent to her personal email account show, dos Santos reviewed bids from two Portuguese construction firms and a higher quote from a Chinese state-owned construction firm, China Road and Bridge Corp. One month later, the general director of dos Santos’ construction and development company, Landscape, announced that China Road had won the job with a bid $50 million higher than the lowest bid. The Chinese company provided good financing prospects from the superpower’s trade agency, according to internal emails justifying the choice.

China Road was a favored contracting partner of the Angolan government. At the time dos Santos’ company chose China Road as a business partner, it was barred from participating in any project financed by the World Bank following allegations that the company engaged in “fraudulent practices” on road construction deals in the Philippines. China Road told ICIJ the company complies with the law and opposes all forms of corruption.

When a lawyer for the cash-strapped Ministry of Finance (MoF) said it couldn’t afford to cover a $232.5 million budget overrun on the project, Isabel dos Santos dealt with it personally, records show.

Replying to her project coordinator on her iPhone 30 minutes after receiving news of the possible snag, dos Santos wrote: “I don’t think it’s a problem, because we’ll talk to the MoF right away.” She would help the ministry fill the multimillion-dollar hole by spearheading a consortium of local banks or identifying other sources of funds, dos Santos wrote.

A Dutch trade agency agreed to provide credit insurance for the dredging and land reclamation part of the work, and the $1.3 billion job went forward. Urbinveste and another dos Santos company, Landscape, stood to receive about $531 million, more than 40% of the total spending. Some of that money was to be distributed to subcontractors, and it isn’t clear how much Urbinveste and Landscape ultimately collected.

Dos Santos said in the BBC interview that she didn’t profit from the deal.

Leen Paape, a corporate governance professor at Nyenrode Business University in the Netherlands, examined Luanda Leaks records at the request of ICIJ partner, Trouw.

Urbinveste’s budget contained red flags, Paape said, including $100 million earmarked for project management and other unspecified costs. Such a large amount for project management, he said, “is not normal.”

The redevelopment plan quickly ran aground. Today, the site of the former Areia Branca community is an empty spit of sand dotted with grass and scrub trees. Many former Areia Branca residents live less than 200 yards away in a slum littered with dead birds and rotting food and swarming with flies and mosquitos. Residents live in small huts of corrugated tin and wood, some sitting atop a mix of sewage sludge and mud that comes in at high tide. Many share beds draped in mosquito nets.

Among them: Talitha Miguel, 41, a teacher and mother of four. On a Sunday afternoon in October 2019, she sat outside her shack with three friends, baking small golden brown cakes for the market amid the sound of radios blaring popular music. Flies hovered around them. Miguel said the pushed-out residents now have no running water and only sporadic electricity. The area periodically floods, and the water surges into their houses with waste from the bay.

“In Areia Branca, life was hard, but we had a fridge, a TV,” Miguel said. The houses were bigger, and they didn’t flood. “We could breathe pure air,” she said. “We stayed in front of the sea. We had trees. We lived healthy.”

A friend in Dubai

In the spring of 2016, dos Santos and Dokolo bought a $35 million yacht, the Hayken, through a shell company in the British Virgin Islands. After its registration with an Isle of Man wealth-management firm, the six-cabin, Dutch-built craft cruised the Mediterranean.

The Hayken was floating near Monaco on June 2 when the news broke: the dos Santos administration had fired the Sonangol board and named the president’s daughter to run the state oil giant, with its annual revenue of nearly $14 billion. Africa’s richest woman was now also one of its most powerful.

Dos Santos later insisted that she was chosen because of her business experience, not family ties. She said her goal was to reform the bloated bureaucracy.

The new administration at Sonangol brought in the same advisers who helped dos Santos land the earlier Sonangol restructuring contract: Boston Consulting, PwC and Vieira de Almeida, the Lisbon law firm. Her administration tapped Sarju Raikundalia, then a senior executive at PwC’s office in Angola, as Sonangol’s chief financial officer. As her stand-in at board meetings, she relied on her top personal financial adviser, Mário Leite da Silva, according to a government document.

Six weeks after dos Santos took charge of Sonangol, a travel agent booked Silva on a trip to Dubai, records show. The skyscraper-filled commercial hub is famous for its tax-free trade zones, financial secrecy and lax enforcement of laws against money laundering. Her lawyer, Jorge Brito Pereira, arranged a trip to Dubai around the same time.

Travel agents reserved luxury hotel accommodations for the two dos Santos confidants under the account of Wise Intelligence Solutions, the Malta company that won the Sonangol restructructuring contract.

Neither Pereira nor Silva responded to requests for comment from ICIJ and its media partners.

Dos Santos kept a Dubai home at the Bulgari Resorts, a high-end complex located on a private island in the Jumeirah Bay area. In corporate papers filed in Malta, attorney Pereira listed the complex as dos Santos’ residential address.

In January 2017, a new consulting firm with ties to dos Santos popped up in an office at the sprawling Jumeirah Lakes Towers nearby. Ironsea Consulting, which would soon be renamed Matter Business Solutions DMCC, had the same sole shareholder, Paula Cristina Fidalgo Carvalho das Neves Oliveira. Silva was a director of Matter, records show.

Oliveira, 48, a Portuguese businesswoman with Angolan and Portuguese addresses, has a background in human-resources consulting. Oliveira and dos Santos had been in business together since 2009, records show. They owned one of the fanciest restaurants in Luanda, called Oon.dah. And they were partners in a company called UCALL, which did employee evaluations for Sonangol.

Through her UK law firm Vardags, Oliveira denied wrongdoing and said that any implication she was “some sort of stooge sitting as proxy for Mrs. dos Santos” is false.

She said dos Santos hired her company to oversee the Sonangol overhaul because of her experience and consulting know-how. Matter coordinated meetings, recruited and managed experts, and made presentations to Sonangol’s board, her lawyers said.

Oliveira said that dos Santos “has no legal or management role in Matter” and that fees were legitimate and properly recorded.

Dos Santos would later say that working 14-hour days, while pregnant, she helped get Sonangol back on solid footing. She improved its bookkeeping system, she said, hired people based on merit, reduced costs and boosted transparency.

Swift exit

From her seat in the VIP section, dos Santos watched as her father, José Eduardo dos Santos, walked a red carpet in Luanda’s Republic Square. In September 2017, he handed over power at the inauguration of his handpicked successor, João Lourenço.

A former defense minister, Lourenço took office with a vow to tackle corruption. The dos Santos era was rapidly coming to a close.

Inside Sonangol, the scramble began.

On Nov. 7, 2017, two months after Lourenço’s inauguration, the head of Sonangol’s subsidiary in the United Kingdom learned that she was about to be replaced.

Maria Sandra Lopes Julio, chief of Sonangol’s UK unit, said she was sitting in her office when Sonangol’s CFO, Raikundalia, walked in.

“He began by informing me that the Board of Directors of Sonangol EP had decided on my resignation, as part of the ongoing transformation process, and that I would be replaced by Mrs. Maria Rodrigues,” Julio wrote in a five-page letter to Angola’s petroleum minister.

Julio wrote that Raikundalia told her that she wasn’t being terminated for incompetence. In fact, he praised her performance.

“I couldn’t help but be amazed,” Julio wrote.

Three days after Julio’s dismissal, Sonangol signed a contract for consulting services with Matter Business Solutions, the Dubai company owned by dos Santos’ business partner, Paula Oliveira. Signing for Sonangol: The new U.K. chief, Rodrigues. Oliveira signed for Matter.

The signatures cleared the way for a massive payment to the consulting firm in Dubai.

In a telephone interview, Rodrigues told ICIJ that she had worked at Sonangol since the early 2000s. Her brother married, then divorced, a sister of José Eduardo dos Santos before he became president.

Rodrigues said that she remembers signing only one document during her short stint as Sonangol’s U.K. chief, though she doesn’t recall the subject, and that Sonangol CFO Raikundalia brought the document to London and asked her to sign. Rodrigues said she doesn’t know Oliveira.

The contract stipulated that Sonangol would pay for past and future services provided by Matter.

Five days later, on Nov. 15, 2017, President Lourenço fired Isabel dos Santos as head of Sonangol.

The Angolan news agency reported the firing on a Wednesday at 1.31 p.m. At 6:30 pm that same day, Sonangol asked its Portuguese bankers to pay $38 million to the bank account of Matter Business Solutions. The transaction details appear on a payment order shared by dos Santos with the news agency Lusa. Dos Santos said she approved the transfer order before her dismissal.

Oliveira said the last minute invoicing was an attempt to have accounts settled, “once Matter discovered what had happened regarding Ms. dos Santos, coupled with cash-flow issues that were occurring at Sonangol.”

In all, confidential Songangol records reviewed by ICIJ show, the oil company’s bank executed three payments worth about $58 million to Matter Business Solutions on the day after the president announced her dismissal, Nov. 16.

Three months later, dos Santos’ successor at Sonangol, Carlos Saturnino, held a five-hour press conference and accused her of mismanagement. He said her tenure, which lasted less than 18 months, had been marked by improper business practices — including excessive compensation, conflict of interest, tax avoidance and an excessive number of consultants.

Saturnino alleged that dos Santos had approved upward of $135 million in consulting fees, with most of those fees going to the Dubai consulting company.

He identified 13 companies that had been paid for consulting services, including five with ties to dos Santos. Four others were her trusted advisers: the Lisbon law firm Vieira de Almeida and the global consulting giants PwC, Boston Consulting and McKinsey & Company.

Saturnino didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment by ICIJ and partners.

Dos Santos said in a recent interview that the payments were for legitimate services that consultants had already delivered.

She also offered a detailed response in a 10-page letter to Saturnino. Dos Santos wrote that when she was still head of Sonangol, its board approved the contract to the Dubai company, Matter Business Solutions.

Matter Business had been responsible for managing consultants for the Sonangol restructuring, she said, adding that she had no connection to the firm. Dos Santos said she abstained from voting on the contract “to ensure no conflict of interest.”

Through her lawyers, Oliveira told ICIJ that dos Santos “has no legal or management role in Matter whatsoever” and that she is not an owner.

“The fees paid to Matter for their consultancy services were legitimately occurred and fully recorded in Matter’s audited account,” the lawyers said. “Any allegations that Matter or Ironsea were involved in (or set up to facilitate) the embezzlement of funds from Sonangol is patently false.”

In the weeks and months after the firing, dos Santos proclaimed her innocence on Twitter and Instagram. She denied ever engaging in favoritism or receiving improper payments.

“It’s nothing but a circus, a performance,” she said in the interview with the Lusa news agency.

She dismissed unflattering stories as “fake news,” called billing allegations unfounded and blamed her predecessor at Sonangol for overspending.

“I like to think that I have responsibility for the breadwinners of many families,” she said. “We worked at Sonangol with a sense of mission, with a spirit to save the company, and we did it.”

In March 2018, Angolan prosecutors opened a preliminary probe, and a court issued a summons for dos Santos to appear for questioning in July.

She didn’t appear. She claims she didn’t receive the request.

Under siege

Dos Santos’ entire business empire was under siege. The arbitration panel at the International Chamber of Commerce ordered Unitel, which she co-owned with Sonangol, to pay its Portuguese shareholder, PT Ventures, more than $650 million for breach of contract. Her lawyers told ICIJ that the arbitration court found the controversial loans to her shell company caused “no damage.” The ruling is confidential.

President Lourenço canceled her public works contracts, including the Luanda redevelopment plan. Angolan authorities said they uncovered overpayments and other irregularities such as phony invoices, noncompetitive bidding and improper subcontracting.

Angola’s state diamond-trading company severed ties to dos Santos, and her diamond exploration licences were revoked. The head of the state diamond company, Eugénio Pereira Bravo da Rosa, told ICIJ partners that its investment in Dokolo’s luxury jewelry business was a financial disaster. The company expects losses on the deal to exceed $200 million, Bravo da Rosa said.

Pressed by ICIJ, Angolan officials last month released more than 400 pages of documents from Sonangol about dos Santos’ business activities, including emails and financial records and invoices submitted by Matter Business.

In responses through lawyers, dos Santos questioned the veracity of documents ICIJ reviewed.

Last year, the day before Christmas, dos Santos said, she got news from a group on WhatsApp. A court in Angola had frozen her personal bank accounts, those of her husband and her stakes in some of the country’s largest companies, including phone provider Unitel.

The government said the couple and Silva, the financial adviser, were suspected of causing Angola to lose more than $1 billion through business deals gone awry. According to investigators, Portuguese police intercepted $11 million that dos Santos tried to transfer to Russia.

Dos Santos called the allegations false and vowed a legal fight.

Angolan prosecutors say they are collaborating with authorities in the U.S., U.K., Switzerland, Brazil, Portugal and Congo. They say the intricacy of dos Santos’ shell empire is making the job difficult. So far, they have uncovered 31 companies with links to dos Santos outside Angola, prosecutors said.

ICIJ found many more. Since 1992, dos Santos and her husband have created or invested in at least 400 companies and subsidiaries in 41 countries, an ICIJ review found. Ninety four of these companies are registered in secrecy jurisdictions, including Dubai, Mauritius and the British Virgin Islands, ICIJ found.

‘It’s Armageddon’

Many companies and executives who did business with dos Santos declined to say anything about their relationships with her.

After receiving detailed questions from ICIJ and its partner the BBC, accounting giant PwC said it planned to terminate its relationship with dos Santos family businesses.

Van Oord said it learned of the 2013 evictions only after questions from ICIJ partners Trouw and Het Financieele Dagblad. The families were removed before the company’s involvement in the project. It promised to “use its leverage” with the Angolan government and contractors to ensure compensation.

Angolan authorities have identified only Isabel dos Santos, her husband and Silva as criminal suspects.

In an unrelated case, her brother, José Filomeno dos Santos, is accused of helping transfer $500 million from Angola’s sovereign wealth fund to the U.K. The Angolan parliament recently voted to impeach Isabel dos Santos’ half-sister Welwitschea dos Santos.

In voicemail messages left with an ICIJ reporter, Welwitschea dos Santos denied any financial link to Isabel or her father. She accused President Lourenço of getting her kicked out of Parliament, and she has appealed the decision. “I believe none of the sides are right,” she said.

José Filomeno dos Santos did not respond to a letter seeking comment, nor did Isabel dos Santos’ top lieutenant, Silva. Her lawyer, Brito Pereira, also didn’t respond.

Her husband, Dokolo, denied using offshore entities to improperly avoid taxation. He blamed the new government for his and his wife’s problems.

Dokolo said through his lawyer the couple had been the victim of a hacking attack and that ICIJ’s questions may be based on forged documents.

“It’s Armageddon,” Dokolo told Radio France Internationale. “The regime claims to act in the name of the fight against corruption, but it does not attack the agents of public companies accused of embezzlement, just a family operating in the private sector,” he said.

No Western company has been accused of any wrongdoing in the Angolan government’s investigation. Isabel dos Santos’ father has also not been named.

The current president, João Lourenço, did not respond to allegations that he is conducting a “witch hunt” against the dos Santos family. Lourenço also did not comment on criticisms that his administration hasn’t done enough to fight corruption.

Isabel dos Santos continues to insist that she made all her money during her father’s rule solely by “taking risks and hard work.”

President Lourenço’s government, she says, is seeking to undermine “the legacy of President dos Santos and what he has achieved.”

“There is an orchestrated attack by the current government that is completely politically motivated,” she said in the BBC interview.

The family says it no longer feels at home in Angola. José Eduardo dos Santos lives in a heavily guarded, walled compound in an upscale neighborhood of Barcelona. Isabel has moved back to London, where her children attend school.

Dos Santos says that she can’t go back because she fears for her safety and that she remains committed to Angola. In interviews with British and Portuguese media outlets, she emphasized that her companies are among the country’s biggest taxpayers and employ thousands. She told Bloomberg News that she worries the asset freeze could doom her companies.

Until her recent legal struggles, dos Santos often shuttled between Lisbon and London while attending conferences in New York, Russia and China.

This month, dos Santos was scheduled to attend a gathering of the global elite, the World Economic Forum at Davos, Switzerland. Unitel is a partner.

Last week, the Forum said she would not be attending.

Editing by: Ben Hallman, Dean Starkman, Emilia Diaz-Struck, Richard H.P. Sia, Tom Stites, Joe Hillhouse, Fergus Shiel, Margot Williams, Hamish Boland-Rudder, Amy Wilson-Chapman and Carlos Monteiro.

Contributors: Micael Pereira, Karlijn Kuijpers, Sonia Rolley, Kyra Gurney, Christian Broennimann, Margot Gibbs, Anita Raghavan, Antonio Cucho, Mago Torres, Pauliina Sinauer, Rigoberto Carvajal, Anne L’Hote, Soline Ledésert, Jelena Cosic, James Oliver and Gerard Ryle.