JACKSON, WYOMING — The honky-tonk bar under neon lights on the town square serves Grand Teton Amber Ale and Yellowstone Lemonade. The Cowboy Coffee Co. offers bison chili and the Five & Dime General Store sells Stetson hats and souvenirs made from bullets.

In this tourist-friendly Western town, home to four celebrated arches fashioned from elk antlers, lawyers and estate planners draw customers with something far more exclusive.

It’s called the Cowboy Cocktail, and in recent years, the coveted financial arrangement has attracted a new set of outsiders to the least populated state in America.

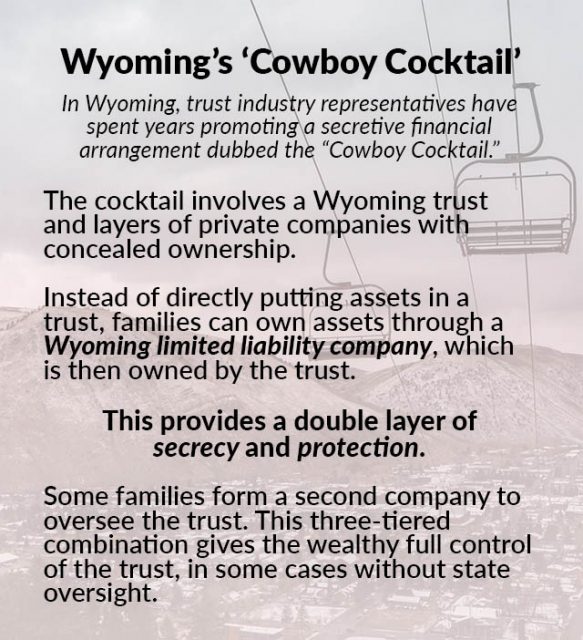

The cocktail and variations of it — consisting of a Wyoming trust and layers of private companies with concealed ownership— allow the world’s wealthy to move and spend money in extraordinary secrecy, protected by some of the strongest privacy laws in the country and, in some cases, without even the cursory oversight performed by regulators in other states.

Millionaires and billionaires from around the world have taken note. In recent years, families from India to Italy to Venezuela abandoned international financial centers for law firms in Wyoming’s ski resorts and mining towns, helping to turn the state into one of the world’s top tax havens.

A dozen international clients who created Wyoming trusts were identified in the Pandora Papers, a trove of more than 11.9 million records obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and shared with The Washington Post, exposing the movement of wealth around the world. The documents offer a rare look at Wyoming’s discreet financial sector and the people who rely on its services.

One was Moscow billionaire Igor Makarov, named under a 2017 law requiring the U.S. Treasury Department to list oligarchs and political figures close to the Russian government. Makarov’s company faced questions in the past about controversial transactions with Russia’s state-owned gas giant and about possible influence peddling involving the daughter of a U.S. congressman.

The matriarch of Argentina’s Baggio family, whose beverage company was accused by local officials of dumping industrial waste and whose son is embroiled in a money laundering investigation, also moved the management of its wealth to Wyoming.

So did the late Kalil Haché Malkún of the Dominican Republic. The polo player and army officer managed the private estates of reviled Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo, who ordered the deaths of political enemies and thousands of Haitians.

For years, anti-money laundering experts and law enforcement have warned federal and state lawmakers that suspect money was flowing into U.S. tax havens, eluding taxing authorities, creditors and criminal investigators. In Wyoming, with the support of state lawmakers, the industry charged ahead, promoting a suite of financial arrangements to potential customers around the world.

At the heart of those arrangements are trusts, legal agreements that allow people to stash away money and other assets so they are protected from creditors and incur few or no tax obligations for themselves or their heirs. In exchange for these benefits, trust owners appoint an independent manager — typically a relative, friend or financial adviser — to determine when and how money is invested and spent.

Wyoming is one of a small number of states that allow customers to place a private company — often controlled by family members — at the helm of their trust, ensuring complete control of the assets and an additional layer of financial secrecy.

Some of the companies are unregulated, exempt from periodic examinations and other state scrutiny.

Customers can also establish a second company inside their trusts to hold the assets, such as property and bank accounts, concealing wealth behind yet another corporate layer.

It’s like a wrapped gift inside a wrapped gift. The more wrapping you put on, the harder it is to figure out if there has been tax avoidance or evasion or even financial crime. Very few people know what you’re doing. — Trust and estate expert Allison Tait

Using this approach – the Cowboy Cocktail – wealthy people can move money into the United States and invest and spend it with a level of anonymity found in few other tax havens.

“Wyoming is advertising itself as the new onshore-offshore — it’s going to get the clientele,” said University of Richmond law professor Allison Tait, a trust and estate expert who has studied the state’s layered financial instruments, including the cocktail.

“It’s like a wrapped gift inside a wrapped gift,” she said. “The more wrapping you put on, the harder it is to figure out if there has been tax avoidance or evasion or even financial crime. Very few people know what you’re doing, basically.”

The Haché family did not respond to requests for comment. Through his attorney, Makarov said the Treasury Department list was copied from a public source and “widely discredited,” that he has no personal relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin and that he has never been charged with criminal wrongdoing. The attorney said Makarov’s Wyoming trust was properly disclosed.

A representative for the Baggio family declined to comment. The family has previously said that it reported the Wyoming trust to officials in Argentina.

There is no evidence in the Pandora Papers documents that the trusts in Wyoming sheltered criminal proceeds.

In a competitive global market, Wyoming’s financial incentives have stood out. One trust company 8,700 miles away in downtown Singapore recommended Wyoming on its website as a go-to tax haven that would “completely shield” clients’ names and assets. “Offshore Wyoming, USA,” noted another firm, this one near the Dnieper River in Ukraine’s bustling capital, Kyiv.

Trust companies in Wyoming now manage at least $31.5 billion in assets, according to the state.

Time and again, Wyoming lawmakers suggested the industry would bring jobs and other economic benefits to a state that has long depended on special taxes imposed on coal, oil and other natural resources.

“It’s friendly for business is the bottom line,” said former Republican House member Bunky Loucks, who spent 10 years in the state legislature. “We were hopeful…just to be on the cutting edge.”

Hoped-for tax revenue, however, did not materialize. The Republican legislature rebuffed sporadic calls for even a small tax on the profits of companies that create trusts.

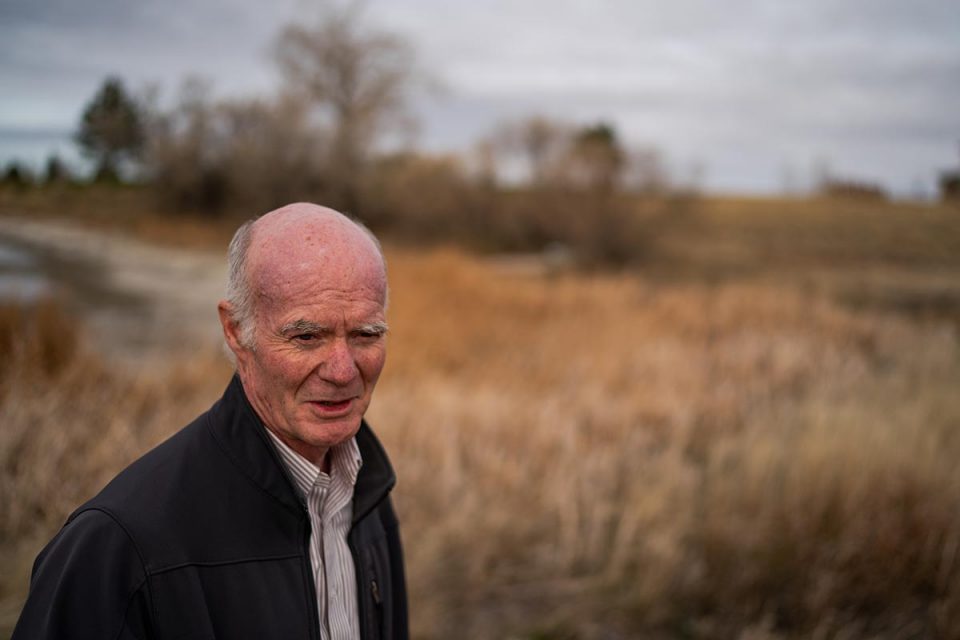

Former Republican lawmaker Michael Von Flatern, who unsuccessfully pushed to tax the industry, said lawmakers did not consider all possible sources of money that could flow into the state.

“We never thought about the oligarchs or the dictator’s friends,” he said.

“Wyoming home cooking”

In 1977, lawyers and accountants for an out-of-state oil company helped persuade Wyoming to authorize a financial arrangement found nowhere else in America.

State lawmakers approved the formation of limited liability companies, now widely used across the country to help conceal the identities of owners and protect their assets from creditors.

The same law had failed twice in Alaska but supporters found a willing home in Wyoming, which skirted bankruptcy in the 1960s and by the ‘70s was heavily dependent on tax revenue generated by fossil fuels.

“We’re sort of at the whim of what happens with market prices worldwide,” said Phil Roberts, a history professor at the University of Wyoming. “There was a good deal of consensus in those days that we have to diversify our economy…[Lawmakers] would try every angle.”

Over the next three decades, lawmakers modified the groundbreaking law, including changes that made it easier for company owners to obscure their identities. “Wyoming home cooking,” industry representatives, lawmakers and legislative advisers called the changes.

Lawmakers also encouraged the growth of the trust industry, adopting more than 100 changes to the state’s trust laws by 2011. Around the same time, the Cowboy Cocktail and its variations took off.

“It’s not the latest trendy cocktail on the club scene,” one trust and estate planner from Georgia noted on his website. “A Cowboy Cocktail is a double-barreled approach to asset protection that may be the best thing since sliced bread.”

“ALAKAZAM! Ultimate Cowboy Cocktail!” wrote two attorneys, one from Wyoming and the other from Tennessee, in a presentation about the novel setup to tax planners.

The addition of private trust companies a critical component of the cocktail, was particularly appealing to customers seeking higher levels of control and privacy.

“Keep it in the family,” Frontier Administrative Services in Jackson posted on its website, which noted that it serves dozens of private trust companies.

Wyoming offers two types of private trust companies, both generally recommended for those with trust assets of $100 million or more. One is reported to the state; regulators with the Division of Banking review company operations. Attorneys say that the regulated option can help families avoid unexpected tax bills and other inquiries.

The other option is an unregulated company, allowed under Wyoming law. Unregulated private trust companies operate outside the supervision of the state and provide an even higher degree of secrecy.

Wyoming has seven regulated private trust companies. Officials say they do not know how many unregulated companies exist. A committee of lawmakers in 2018 estimated that lawyers were creating as many as 100 unregulated companies a year.

The financial tools found broad support among state lawmakers, who over nearly two decades backed almost 20 laws to bolster the industry, with few dissenting votes, state records show.

Wyoming is now among the 10 least-restrictive, most customer-friendly trust jurisdictions in the world, according to a study last year by Adam Hofri-Winogradow, a law professor and trust expert at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The study ranked Wyoming ahead of South Dakota, an international tax haven featured in the Pandora Papers investigation published by The Post and ICIJ in October.

Wyoming, South Dakota, Alaska, Delaware and Nevada were named in October by the European Parliament as hubs of “financial and corporate secrecy”.

For some time now, the U.S. has been the weak link in the international anti-money laundering regime. — Josh Rudolph

Citing the Pandora Papers, the group urged the U.S. to better police the industry and join a coalition of more than 100 countries that automatically share information about the financial transactions of noncitizens.

“For some time now, the U.S. has been the weak link in the international anti-money laundering regime,” said Josh Rudolph, a member of the National Security Council staff in the Obama and Trump administrations. “The European Parliament is absolutely right — we are the enablers.”

World’s elite seek out Wyoming

The Pandora Papers records, while not comprehensive, reveal a series of Wyoming transactions mostly between 2016 and 2019 as well as the people behind them. Some moved the management of their wealth from traditional tax havens in Europe and the Caribbean, capitalizing on key ingredients of the Cowboy Cocktail.

Makarov, the Russian billionaire, turned to Wyoming in late 2016, setting up a Wyoming trust and an unregulated private trust company to manage it, Pandora Papers documents show. Makarov put a twist on the cocktail: placing into the trust three companies established in the tight-lipped British Virgin Islands, including one that owned a 13-seat private jet.

“Like a Cowboy-On-The-Beach Cocktail or something,” Tait, the Virginia professor, said of the arrangement.

Makarov and the oil and gas company he founded, Itera, faced scrutiny in Europe and the United States. In the early 2000s, media reports raised questions about whether the company had improperly received loan guarantees and other aid from Russia’s state-controlled gas company, Gazprom. Shortly after, the U.S. Trade and Development Agency suspended a $868,000 grant to Itera.

In 2006, the FBI searched Itera’s Florida office in connection with an influence-peddling investigation involving a U.S. congressman. In 2009, Italian media reported that Makarov was investigated for potential ties to Mafia figures and that the investigation was at risk of being closed because of a lack of cooperation by foreign authorities.

In an unclassified report in 2018, the Treasury Department included Makarov on a list of Russian oligarchs.

Through his lawyer, Makarov said he has no ties to organized crime and called the Italian media report “completely false.” The U.S. influence-peddling investigation did not result in arrests or charges against Makarov or anyone associated with the company, his lawyer, Brian Wolf, said. Gazprom never provided resources or clients to Itera and together they operated in accordance with Russian law, Wolf said.

Makarov established the trust in Wyoming based on professional advice, Wolf said. “All required disclosures have been made and transparency laws have been followed,” he said.

Celia María Agueda Munilla, the 83-year-old matriarch of the Baggio family in Argentina, also set up a trust overseen by an unregulated private trust company in Wyoming. The trust, established in 2018, held a company in the British Virgin Islands with a $7 million account at a bank in Miami, the Pandora Papers show.

Munilla and her late husband founded RPB, one of Argentina’s largest producers of boxed fruit juice and wine. Munilla remains a director of the company, according to the family company website.

For years, media reports, government officials and local residents have accused the company of polluting land and waterways. The company agreed to stop dumping waste in 2016, according to a public statement by local authorities.

Last year, Argentine authorities filed a criminal complaint against a series of businessmen, including one of Munilla’s sons, a majority shareholder, accusing them of burning grasslands for economic gain. The Pandora Papers do not list him as a trust beneficiary of the Wyoming trust.

The Financial Intelligence Unit in Argentina stepped in as a plaintiff in the ongoing case, which it called the “Baggio file,” alleging possible money laundering.

A representative for the family previously said that it declared the Wyoming trust and its assets to Argentina’s revenue authority. Neither the family nor its company responded to questions about the criminal investigation.

One of the more recent transactions described in the Pandora Papers was made by the late Haché, who once served as estate manager to brutal Dominican Republic dictator Trujillo.

The regime ordered the murders of tens of thousands of Haitians, along with three prominent sisters who had protested Trujillo, according to historical accounts.

The regime is also believed to have abducted a Columbia University graduate student and lecturer in New York City before transporting him to the Dominican Republic in a case described by the U.S. Justice Department as a “political murder.”

After Trujillo was assassinated in 1961, his son Ramfis took control of the country and rounded up the assassins, most of whom were killed. Haché allegedly witnessed torture in a notorious Dominican prison but refused to join and fainted, according to two public accounts, one by a foundation that commemorates the men who killed Trujillo and the other by one of the men’s sons. Ramfis, living in exile, was convicted of murder.

Haché later described himself as a businessman; family interests included an oil and lubricant company, records show. In 2019, Haché, his wife and two daughters set up a Wyoming trust and an unregulated private trust company to own two British Virgin Island companies with bank accounts in Miami, the Pandora Papers records show.

Haché and his wife died of Covid-19 last year. His family declined to comment.

In a 2013 interview with a Dominican Republic journalist, Haché defended his connection to the Trujillo regime. “How could I be disloyal to a family that distinguished me with all their affection?” he said.

He added that his loyalty was “to the person who distinguished me, not to … the dictatorship.”

Kept in the dark

Current and former state lawmakers said they always intended to build a clean industry that protected the privacy of reputable clients.

“There are countries out there that want to protect the criminals because they believe it’s of economic benefit to have bad actors fund their state,” said state Sen. Chris Rothfuss, the Democratic minority leader. “We don’t have that interest. We will throw them under the bus as quickly as we can.”

Rothfuss, however, acknowledged that regulators are often kept in the dark by the state’s own privacy laws, left dependent on occasional tips or media accounts for information about trust industry clients.

In October, U.S. lawmakers called for the most significant overhaul of anti-money laundering regulations since 9/11. If approved, the changes would require lawyers and trust companies to investigate their clients and sources of wealth to ensure that suspicious money does not breach the U.S. financial system.

Even with more transparency, Rothfuss said, the state banking division doesn’t have enough staff to monitor industry compliance. “We don’t necessarily have the resources to be proactive,” Rothfuss said.

The Division of Banking has three employees who examine the state’s regulated trust companies. “We are probably slightly overstaffed in this area, but we are anticipating continued growth in this area and want to ensure appropriate resources,” said Albert Forkner, the state’s banking commissioner.

In a statement, the Wyoming Trust Association said it “supports effective and meaningful regulatory oversight of the trust industry.” The association also said that the industry would support increases in the fees paid to the state by regulated trust companies.

Von Flatern, the former lawmaker, said in an interview at his home in Gillette that the scant financial impact by the trust sector over the years has contributed to Wyoming’s fragile economy, undercut by the coal industry’s years-long decline.

In the eastern Wyoming mining town, a rotary drill, an oversize coal shovel and a 411,580-pound engine are displayed in a local park. Coal mines rumble with the sound of earth movers. Trains with dozens of cars haul coal through the city, winding past Lula Belle’s Cafe, where miners gather for coffee before their shifts start.

“If you come in as a trust company or a banker, you don’t pay your way,” Von Flatern said. “We didn’t gain anything.”

Contributors: Brenda Medina and Delphine Reuter at the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Dmitry Velikovskiy at iStories (Russia), Alicia Ortega Hasbún at Noticias Sin (Dominican Republic), Paolo Biondani at L’Espresso (Italy), Sandra Crucianelli and Mariel Fitz Patrick at Infobae (Argentina).