INTERVIEW

‘We wanted to be the voice of the voiceless people of Namibia’

Q&A: Despite facing constant harassment, threats and opposition, pioneering journalist Gwen Lister tells ICIJ that she never lost sight of her mission as an “activist journalist.”

Gwen Lister is a renowned Namibian journalist with a storied career. Known for her efforts to fight apartheid in Namibia, Gwen became the first female editor of a southern African newspaper before going on to co-found two newspapers of her own — including The Namibian in 1985. Gwen was also one of ICIJ’s earliest members, and served as an adviser to ICIJ before becoming an alumni member in 2019.

Lister’s memoir, “Comrade Editor: On life, journalism and the birth of Namibia” was published last year, telling the intertwined story of her career and of journalism in Namibia. We spoke with Gwen about her book, journalism in Africa, and what it means to be an “activist journalist.”

Your book discusses the history of Namibia extensively. Can you describe what it was like to cover apartheid there? How has journalism in the country evolved since?

Obviously it was very, very difficult to cover apartheid, as you can imagine. There was no such thing as press freedom at that time. And obviously the apartheid authorities wanted everyone to agree with them and what they were doing, so any kind of independent media, if it did exist, was given a hard time by the authorities.

So it was very, very difficult indeed. That includes not just media in Namibia, but also in South Africa itself where they had a real battle to keep independent newspapers alive and keep telling truth to the people about what was happening under the jackboot of apartheid.

In 1990, when Namibia finally achieved independence, we came up with a constitution which was seen as something of a shining light on the African continent. It wasn’t just apartheid South Africa that had southern Africa in its grip. Further afield in Africa, there were mostly one-party states and they weren’t very friendly to the independent press either. So Namibia’s constitution which provided for press freedom was certainly a breath of fresh air on the continent and immediately improved things, I think I can say.

You’ve described yourself as an “activist journalist” and how you don’t believe in the concept of objectivity or neutrality in journalism. Can you tell me more about your outlook on ‘taking sides’ when covering a contentious issue? How did you keep your coverage fair?

We were journalists in the apartheid era. There was no way that you could say “well let us be objective about apartheid.” Is it really as bad as everyone makes it out to be? Is it such a terrible thing to oppress black people? So of course we couldn’t be objective. We were very, very subjective about it, and especially here in the sort of mandated territory of Namibia.

We wanted the chance for Namibia to exercise its own self-determination and not be under foreign rule, so to speak, a white minority government that was trampling the rights of our black compatriots underfoot. Certainly, that was like my baptism of fire into journalism, in the apartheid era. Part of my journalism was to try and not only expose what was happening on the ground under apartheid and virtual military rule, but also to change things.

At its root, journalism is about public service and forging a good society. I believe that activism can be combined with journalism, in terms of causes, whatever those causes may be. Ours at the time was basically an illegal regime which was controlling Namibia. Also just to be able to show the outside world what was happening, because nobody really seemed to know. The spotlight of international media certainly wasn’t on Namibia at that time, it was more so on South Africa.

We wanted to stand up for the people, with the people and show the world what was happening to them.

The concept of neutrality in journalism for me is a difficult one. That doesn’t mean to say that when one does one’s journalism that one doesn’t comply with all the normal, fair journalistic practices that one usually employs when writing any kind of news story and getting the other side’s viewpoint as well. Our actual journalism, I think, was balanced and fair. The question of subjectivity was about the things we chose to cover.

There were other media here in Namibia at the time that turned a blind eye to the atrocities happening to SWAPO [independence movement and political party South West Africa People’s Organisation] supporting civilians, who were detained without trial, who were harassed, who were jailed, who were killed. But we were different. We wanted to stand up for the people, with the people and show the world what was happening to them.

Can you speak more about your experiences as a white woman writing about apartheid, and how your perspective may have influenced your coverage?

That’s a difficult thing for me as an individual to answer. I was one of those whites growing up in South Africa who was deeply offended by the apartheid regime and what it was doing. That influenced me from very early on, that people need to stand up and be counted. Especially white South Africans and Namibians back then needed to stand up and oppose this unjust system and that it shouldn’t just be our black compatriots who were protesting, but that we should join in the cry for equality and justice for all.

I was so committed to what I was doing that I never really stopped to give much thought to why I was doing what I was doing and how the color of my skin influenced me in that reporting. I knew that I had to get as close to the people as possible that I was reporting on. I did that from a very early stage so that I wasn’t simply reporting on them, but I was also very aware of their wishes and aspirations for the future of Namibia.

I did stand out a bit like a sore thumb because there were not many journalists who were standing up at that time to oppose the system, whether they were black or white for that matter. Especially in the smaller Namibian context it was very obvious that I was a white person standing up for what was then perceived to be a black cause. That was fine with me.

What role did you and fellow journalists play in Namibian independence and fighting South Africa’s racist regime?

One of the major things we did was conscientize the outside world to what was happening in Namibia. There was very little in terms of international spotlight to what was happening then. There was a lot of attention paid to South Africa as the sort of home of apartheid, but much less so on Namibia. I think most journalists saw it as this rather big country with very few people. Geographically located between South Africa and Angola, it wasn’t very important in the greater scheme of things. But of course it was.

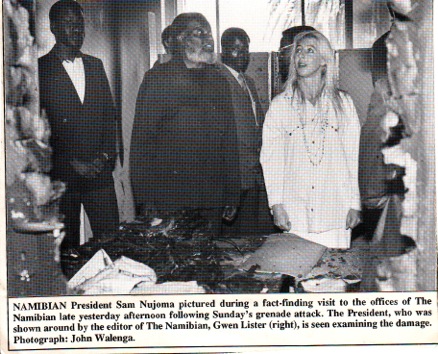

Namibian independence was absolutely critical to what later happened in South Africa, the fall of apartheid there and the release of [Nelson] Mandela, and so on. We tried to make a difference by exposing the atrocities here and we did so at a great personal cost. Most of my staff and myself were exposed to a lot of harassment, detentions, arrests, assassination attempts and all sorts of things. And also attacks on the newspaper itself.

South Africa wanted to show the world that everything was fine in Namibia and that everybody agreed with South African colonialism, which was not the case. It’s difficult and I should be the last person to quantify what our contribution might have been to the eventual self-determination and independence. But I do think that The Namibian, which was the only paper of its kind speaking out here against what was happening, certainly conscientized the world of what was happening and in some ways helped to hasten an internationally recognized settlement for the country.

We wanted to be the voice of the voiceless people of Namibia who had had no recourse up until the point the Namibian was started. Most of the SWAPO leadership were banned from speaking on the national broadcaster and they certainly weren’t quoted much in newspapers. We sort of gave a human face to SWAPO because the South African government would condemn them as terrorists and communists, and we tried to show the world that that’s not in fact the case.

We tried to change the perceptions around the liberation movement and to expose the human rights violations happening in the country in general, particularly in Northern Namibia which was basically in the grip of the military under a dusk-to-dawn curfew in conditions that were really terrible for the people who were often just caught in the cross-fire.

You co-founded two newspapers (the Windhoek Observer and then The Namibian) and were the first female editor of a southern African newspaper. Why did you decide to start your own media outlets? What was it like to transition from being a reporter to a leadership role, and how did that influence your goals or objectives as an activist journalist?

To cut a very long story short, the newspaper I started before The Namibian, I was on that paper for six years. I founded that paper with the then editor. It was a very vibrant newspaper and very progressive in its outlook. Eventually, because we didn’t have any finances, the white business community — because business was dominated by whites — would not support the newspaper in terms of advertising. I think the then editor just got tired of fighting the good old fight and felt that my politics — especially after the newspaper was banned — decided that he didn’t want to go that route anymore.

After I was demoted and the staff protested, we later all walked out, it took me about a year from then to start another newspaper because I realized then that none of the media in Namibia that existed were now going to speak out and do the things that we had been doing on the Observer to expose what was happening in Namibia under South African rule. That voice had now been neutralized. I thought it was important to give it another try and start another newspaper even though the odds were greatly against us and it was not easy to do that or get funding. I had nothing and certainly no finances to do so. I felt I had to at least make the attempt.

I’m happy to say that all these decades later, The Namibian is still alive and well and still the biggest selling newspaper in Namibia. We did survive to tell the tale. It wasn’t an easy one from the point of view of political survival, but neither was it easy in terms of just trying to sustain the newspaper. We beat that obstacle after independence and finally the business community, which was now becoming more integrated, started to support the newspaper. Even a subsequent ban from the independent government of SWAPO in 2000 on the newspaper, because it was then perceived to have become anti-government, didn’t succeed in deterring the advertising.

We survived that as well, which I think we were very proud about because independent media is something that’s very close to my heart and I think very close to the hearts of all those journalists who worked on the publication.

Your memoir includes a lot of stories and interesting people that you met over the course of your career. Who or what would you say was an especially impactful experience or individual you encountered during your years as a journalist?

I’m not a person who has many heroes. I worked in an era where there weren’t many people who could mentor me. I did what I did by trial and error and following my gut instinct. I can’t say that there were people I could look up to and say, “Wow, that person really inspired me to do what I did.” I think I’ve always followed my own star. It’s encouraging to see today that there is a lot of support for women making their way in the world of journalism in particular, and they have many role models.

We can look at [people like Nobel Peace Prize winner] Maria Ressa and all the other great women journalists who are around today. But in those days, the ’70s and the ’80s, there wasn’t much of that and not a lot of support in terms of women’s organizations. There were anti-apartheid solidarity groups that always spoke out if I was arrested, detained or charged on the various draconian legislation. But there was nobody that I could really lean on and count on for support.

That having been said, there was support and some of the people I do admire include of course, Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who in those years of apartheid would come up to Namibia from time to time in the course of his church work. He never failed to pop in our offices and to give encouragement to our journalists to continue.

What’s next for you? Any hopes for the journalism field or the media landscape in your region? What do you think of independent journalism across Africa today?

I’ve done a lot of radio work in the past, but I’m a print person in bone and marrow. I love the medium of print and the survival of print is very important to me. In the context of press freedom and independent press, I think that print has been at the forefront of some of the best investigative journalism over the years.

Organizations like the ICIJ for example, have come up since 2000, and they’re wonderful initiatives, bridging the gap between journalists across the world to do collaborative investigative work. I see a lot of hope in that. Equally so in Africa, there is a lot more networking in terms of investigative journalism. I think that’s very positive.

Some of the challenges of journalism today, probably not only in Africa but in other parts of the world, we mustn’t let our standards slip because of the digital tsunami and social media onslaught that is pointing people in the direction of entertainment and clickbait. Somehow, someday, we need to break through with serious journalism. Good journalism is something that can make a real difference and can help empower people with the kind of information they need to be the best citizen they can be in a democracy.

I’m hoping that journalism can win that battle of eroding trust, which is prevalent not only in journalism. People around the world seem to have lost trust in all kinds of institutions, but journalism is what worries us most. I’m hoping we can find a way forward to sustain good journalism. I hope that print always survives in some form or another in Africa, mainly because of the importance of literacy. But also just to find ways and means to sustain good journalism and to keep press freedom alive.

As I’ve said on many occasions, the battle for press freedom, wherever it may be, whether it’s in the U.S., Africa or in other draconian parts of the world, is a battle that’s never fully won. We need to be activists all the time to hold on to the banner of press freedom and keep making sure that governments are creating and enabling an environment for independent journalism to not only thrive, but also to survive.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.