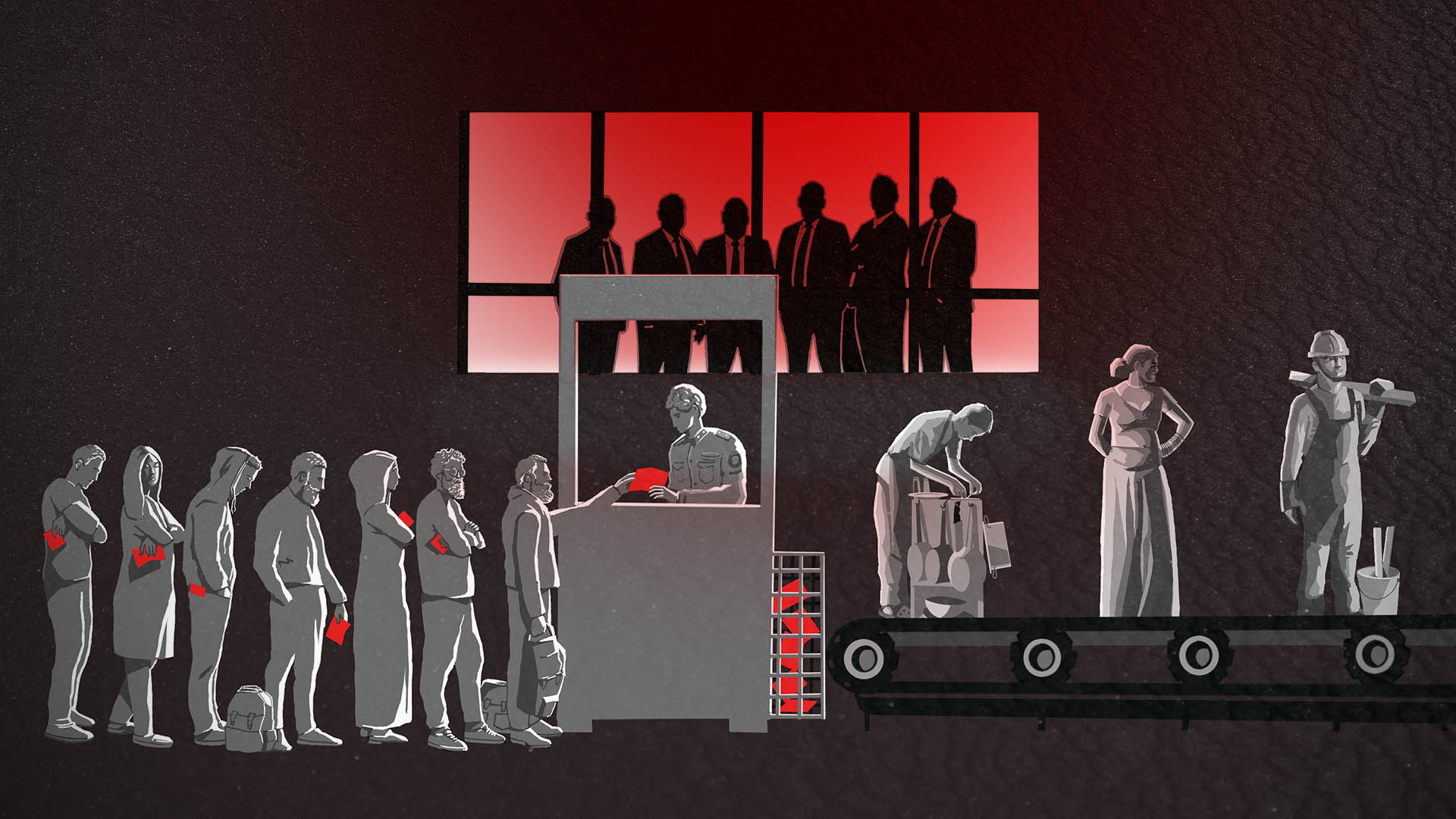

On any given day, the United Nations estimates, nearly 28 million adults and children around the world are trapped in jobs that are so oppressive that they amount to modern slavery or human trafficking.

They are forced to work long hours for little or no pay, toiling on farms and construction sites, in sweatshops and restaurants, as janitors and, in some cases, sex workers. They are exploited by recruiters and employers who use their poverty, isolation and immigration status against them, often threatening them with violence, arrest or deportation or ensnaring them in debts they struggle to repay.

A new investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and other media partners has begun examining human trafficking in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and the United States.

The investigation, Trafficking Inc., focuses on two forms of human trafficking: labor trafficking and sex trafficking. Both involve using force, fraud or coercion to induce someone to work or provide a service.

ICIJ and its reporting partners are working to bring to light untold stories of hardship and abuse suffered by trafficked people — and expose the networks of companies, individuals and business practices that set the traps and profit from them.

The investigative team includes journalists from ICIJ, Reuters, NBC News, WGBH Boston, The Washington Post, Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism, the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, the Guardian US and the Investigative Reporting Program at the University of California, Berkeley.

Stories released by the partnership in late 2022 have won several accolades, the New York Deadline Club’s prize for business investigative reporting and a selection as one of the year’s top investigations in the Arab world.

Stories released include articles by ICIJ, The Post, NBC and ARIJ that revealed that many foreign workers for defense contractors on U.S. military bases in the Persian Gulf have been targets of abusive labor practices — including illegal recruiting fees that force migrants who are paid as little as $1 an hour to work for years before they’ve paid off their debts.

Other stories released in 2022 included pieces by WGBH that revealed flaws in U.S. protections for trafficked workers and the failure of Massachusetts authorities to punish labor traffickers who prey on vulnerable workers.

A story copublished in June 2023 by ICIJ and Reuters examined sex trafficking between Nigeria and other African nations and the United Arab Emirates. The story was based on court records and other documents and interviews with 25 African women who described being lured to the UAE by traffickers along with dozens of interviews with humanitarian workers, investigators, Nigerian government officials and others with knowledge of sex trafficking in the Emirates.

Stories published in October 2023 showed how major American corporations profit, directly or indirectly, from employment practices that may amount to labor trafficking, which is defined as using force, coercion or fraud to induce someone to work or provide service. ICIJ spoke with nearly 100 migrant laborers from Asia who told ICIJ that they’ve been subjected to repressive labor practices while working at Persian Gulf locations of four well-known American and British brands: Amazon, McDonald’s, Chuck E. Cheese and InterContinental Hotels Group. The four companies told ICIJ that they were taking the revelations seriously.

Human trafficking is said to be the world’s fastest growing criminal enterprise. In 2014, the United Nations’ International Labor Organization reported that, between them, labor and sex trafficking produce an estimated $150 billion in illicit profits annually. At that time, the organization said 21 million people were working under conditions of forced labor. A report released in September 2022 by the International Labor Organization and a nonprofit group, Walk Free, estimated that, as of 2021, the number of people working under forced labor conditions had grown to 27.6 million.

Keeping workers physically and emotionally isolated is a method of control in many trafficking cases. Employment agents or employers often take away passports and cell phones and tell workers that if they try to leave they will be arrested.

Some recruiters and employers use threats of violence or actual violence to trap and control trafficked workers. But coercion in human trafficking doesn’t always involve direct threats of physical harm. Often workers are lured into well-laid traps that ensnare them in large debts for recruitment fees or take advantage of their precarious immigration status.

In some countries it is a crime to break an employment contract. Authorities often don’t care if the contract was fraudulent or the employer abuses workers.

Under the “kafala” system in Jordan, Lebanon and most Persian Gulf countries, for example, employers exercise wide control over migrant workers’ freedom of movement and legal status. The Council on Foreign Relations, a New York-based think tank, notes that there’s growing recognition the system is “rife with exploitation.”

Beyond the kafala system, immigration laws in many countries — including the United States — leave migrant workers vulnerable to labor abuses.

The toll that labor trafficking takes on workers is wide-ranging and powerful. Along with economic exploitation, they can be exposed to physical and sexual violence, infectious diseases, hunger, unsanitary living arrangements and dangerous working conditions. Surveys of workers who have been trafficked find high levels of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

War, disease, disasters, global warming, poverty and inequality serve as “push factors,” prompting vulnerable workers to seek out new jobs and new lives in new places.

Amid the global Covid-19 pandemic, the United Nations reported that human traffickers had adjusted their business models to the “new normal” created by the disease, especially through “the abuse of modern communications technologies.”

“Most importantly,” the U.N. said, “the pandemic has exacerbated and brought to the forefront the systemic and deeply entrenched economic and societal inequalities that are among the root causes of human trafficking.”

Anyone who has information after labor or sex trafficking can email traffickinginc@icij.org or contact ICIJ via Signal, WhatsApp or a number of other secure platforms.

The Trafficking Inc. investigation is brought to you by:

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

Director: Gerard Ryle

Managing editor: Fergus Shiel

Senior editors: Michael Hudson, Ben Hallman, David Rowell

Reporters: Katie McQue, Maggie Michael, Pramod Acharya

Data editor: Emilia Díaz-Struck

Data reporter: Agustin Armendariz

Associate editor and fact checker: Richard H.P. Sia

Online editor: Hamish Boland-Rudder

Digital editors: Asraa Mustufa, Joanna Robin

Digital producer: Carmen Molina Acosta

Copy editor: Joe Hillhouse

Illustrator: Rocco Fazzari

Reporters and editors

- Yasmena AlMulla (Kuwait)

- Tanka Dhakal (Nepal)

- Carmela Fonbuena (Philippines)

- Karol Ilagan (Philippines)

- Cherry Salazar (Philippines)

- Jenifer B. McKim (United States)

- Sarah Betancourt (United States)

- Molly Boigon (United States)

- Yousef H. Alshammari (United States)

- Melvin Harris Jr. (United States)

- Courtney Kube (United States)

- Andrew Lehren (United States)

- Phillip Martin (United States)

- Didi Martinez (United States)

- Hoda Osman (United States)

- Anna Schecter (United States)

- Paul Singer (United States)

- Alan Sipress (United States)

- Laura Strickler (United States)

- Bernice Yeung (United States)

Media partners

- Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (Jordan)

- Investigative Reporting Program at the University of California, Berkeley (United States)

- NBC News (United States)

- NewYorker.com (United States)

- Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (Philippines)

- Reuters (Egypt)

- The Guardian (United States)

- The Washington Post (United States)

- WGBH (United States)