ACCOUNTABILITY

As US-style corporate leniency deals for bribery and corruption go global, repeat offenders are on the rise

An ICIJ analysis finds a surge in closed-door non-prosecution agreements, with more governments allowing companies to pay to settle cases. But deep-pocketed firms keep breaking the law.

Switzerland’s Novartis AG, which touts breakthrough treatments for cancers and rare diseases, has become the most profitable drug company on the planet. Profits at Italy’s Eni SpA, one of the world’s seven largest oil companies, have quintupled this year, as gas prices soared. And Germany’s Deutsche Bank, well-connected to politicians, royals and oligarchs, recently notched its ninth successive quarterly profit, marking a huge turnaround after years of losses.

Deutsche Bank, Eni and Novartis share another distinction besides power and profit. They were all embroiled in bribery schemes or otherwise accused of making payments to public officials and others to win lucrative business. In the past dozen years, each promised to reform and not to offend again, and each paid to settle its case under the threat of further legal action if they didn’t live up to those pledges.

But the deals didn’t mark the end of legal action against any of the companies. U.S. authorities accused them of engaging in bribery schemes or making improper payments again, sometimes within just a few years.

Eni settled a second case; Novartis a third and then a fourth. Deutsche Bank escaped prosecution four times — on bribery, tax fraud and antitrust charges — and settled a fifth case with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. This year, the bank admitted that it had failed to report new allegations of wrongdoing to the Justice Department in a timely manner, another breach. The punishment? Prosecutors extended oversight by a corporate compliance monitor by nearly one year.

Implicated in this spree of corporate recidivism is a U.S.-contrived enforcement strategy with a dismal record of deterring corporate crime. U.S. authorities routinely offer companies accused of corruption-related offenses a deal: pay a fine, accept a regulatory sanction, or both; adopt reforms and promise to be a good corporate citizen going forward.

The settlements, to resolve both criminal and civil charges, have faced withering criticism from academics, federal judges and other advocates of reform. But U.S.-inspired leniency deals are spreading around the world, according to an investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and media partners in 11 countries.

In criminal cases, negotiated settlements, known in the U.S. as deferred prosecution and non-prosecution agreements, are far easier and far less costly than a trial. They have led to a surge of settlements and financial sanctions that prosecutors and regulators tout as evidence of their success in combating global corruption.

In the past two decades, prosecutors and regulators in 30 countries have negotiated corporate settlements to resolve bribery and other corruption allegations against at least 265 companies, reaping $34.9 billion in fines and other payments, the ICIJ review found.

Settlement payments have soared. In 2000, the highest was $844,000. In 2020, it was $2.5 billion, according to data reviewed by ICIJ.

Critics of the settlements say they fail to prevent — and may even tacitly encourage — the worst sorts of corporate abuses, including the bribing of public officials in foreign countries, which undermines the rule of law and weakens democracy.

ICIJ’s investigation found that shortcomings in the U.S. system are emerging in other countries that have adopted negotiated settlements. These defects include: fines and other payments with no real deterrent effect; individuals not held to account; misbehaving companies that continue to win public contracts; and firms with deep pockets that violate the law over and over.

In early December, ABB Ltd., a Swiss power-technology company, settled bribery allegations related to contracts for work at a South Africa power plant. The $327 million settlement, between ABB and U.S., Swiss and South African authorities, makes the Zurich-based firm the first three-time anti-bribery violator in the U.S., experts say.

“The proliferation of U.S.-style corporate settlements is quite alarming,” said Peter Reilly, a law professor at Texas A&M University. “Rule of law is being undermined, and governments are failing to protect the very people they are charged with protecting — something that both undermines basic fairness and ultimately weakens a democracy.”

For corporate offenders, Reilly said, “it’s like getting out of a legal jam by paying a speeding ticket.”

ICIJ identified 34 companies, 21 of them listed on the Global Fortune 500, that settled cases for alleged bribery or fraud in the last two decades and then violated the law again, often within a few years.

In February, ICIJ and media partners revealed that the Swedish telecom company Ericsson had conducted an internal investigation into years of corrupt practices in Iraq — including possible payoffs to Islamic State terrorists. That review was in progress in 2019, as the company negotiated a $1 billion agreement with the U.S. government to resolve bribery allegations in six other countries.

Within days of publication of ICIJ’s Ericsson List investigation, the United States told the company that it had violated the agreement again, the second breach in less than six months.

It was this pattern of recidivism that prompted ICIJ’s review of corporate settlements.

Defenders of deferred prosecution and other negotiated settlements say they save governments the time and expense of collecting evidence needed to take rich companies to trial, while still holding them accountable for their misdeeds. The deals also reflect a reality of the justice system: that government lawyers are often outgunned by their corporate counterparts, who are richly compensated and have vast resources at their disposal.

Negotiated agreements can protect companies from bad publicity and safeguard their access to public contracts, their supporters say. “A practical incentive is that the case is solved fast and without lengthy and expensive trial and publicity that can be the result of such proceedings,” the Norwegian government told the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, according to a 2019 report on non-trial resolutions.

Peter Solmssen, a corporate lawyer who helped write international guidelines for negotiated agreements, said that when it comes to huge multinationals, “old-fashioned law enforcement” doesn’t work.

“What outcome do we want?” said Solmssen, a former general counsel at Siemens AG. “If we want corporations to pursue corruption actively, to stop corruption when they find it and to turn the corrupt over to the police, then the only mechanisms that will work are non-trial resolutions with effective incentives.”

And, proponents insist, negotiated settlements are better than no enforcement at all. A recent report by Transparency International says that many countries, including major powers like China, Japan and India, conduct limited or no foreign bribery enforcement at all.

If you pay the government, you often won’t get prosecuted. In my mind, it sounds awfully like the very bribes the law prohibits. — civil litigation specialist Dylan Phillips

Dylan Phillips, a lawyer who specializes in civil litigation and has worked on corporate-compliance matters, said companies often view leniency agreements as a cost of doing business. “If you pay the government, you often won’t get prosecuted,” he said. “In my mind, it sounds awfully like the very bribes the law prohibits.”

‘Obliged to swallow the pill’

In Brazil, these corporate settlements are called accordos de leniencia, or leniency agreements. In Switzerland, they are summary penalty orders. In Italy, they are patteggiamento, or plea bargaining. In Canada, they are remediation agreements. In Britain and Singapore, they are called deferred prosecution agreements.

The deals differ in the specifics, but all refer to settlements reached in closed-door negotiations between corporations and prosecutors rather than the outcomes of trials in open court.

A growing number of academics, judges and politicians in the United States have lashed out at the Justice Department for allowing guilty major companies and their executives to buy their way out of accountability.

In 2018, U.S. District Judge Lewis Kaplan said that he was troubled by deferred prosecution agreements but that he had limited authority to challenge them.

“Both the interests of deterrence and the interests of just punishment are better served in all or most cases by prosecution of the individuals responsible,” said Kaplan, who was overseeing efforts by U.S. Bancorp, a financial services holding company, to avoid prosecution on money laundering charges. But, he said, “I am obliged to swallow the pill, whether l like it or not.”

Acknowledging a decline in the number of corporate criminal prosecutions, a top Justice Department official recently announced policies aimed at cracking down on repeat offenders and holding culpable executives and other individuals accountable.

“We need to do more and move faster,” Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco said in a speech at New York University in September. “If any corporation still thinks criminal resolutions can be priced in as the cost of doing business, we have a message: Times have changed.”

The record so far, however, suggests that corporations had ample reason to believe that they could still buy their way out of trouble.

Data compiled by the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime, and analyzed by ICIJ, show that since 2000 the United States has settled the highest number of cases, 360, yielding $17.2 billion in fines and other agreed payments. Brazil, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and France have collectively harvested more than $13.5 billion in agreed payments.

The proliferation of such settlements has encouraged increased secrecy. A review of agreements, audit reports and an International Bar Association study from more than 40 countries showed that most nations don’t disclose the texts of these agreements, which are invariably negotiated behind closed doors.

The World Bank Institute estimates the total amount of corporate bribes paid per year, worldwide, is about $1 trillion. Bribes, anti-corruption experts say, are the single greatest impediment to developing countries struggling to pay for roads, schools, health care and other public services.

And bribery and other forms of corruption damage trust in government, the experts say.

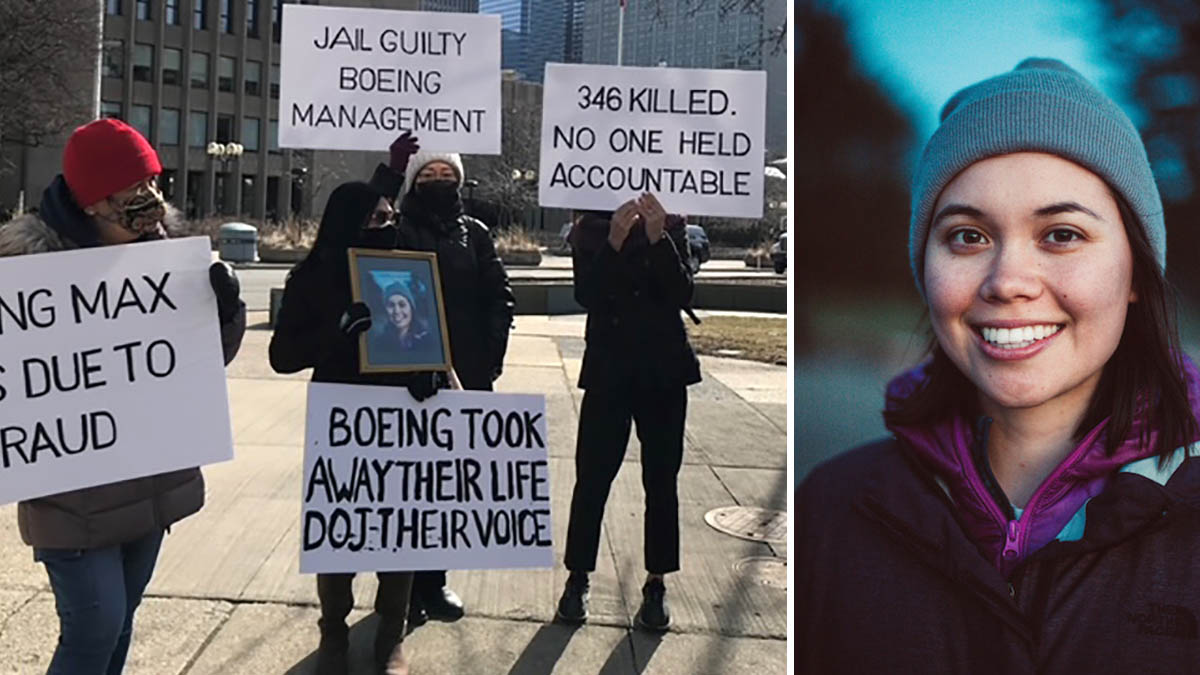

After crashes of two Boeing 737 Max airliners killed 346 people in 2018 and 2019, federal investigators tried to piece together why the aircraft fell from the sky in near nosedives. They were stonewalled by Boeing employees, who concealed design flaws, investigators concluded.

In January 2021, prosecutors allowed the aerospace giant to end a criminal probe of fraud and coverups with a deferred prosecution agreement and a settlement payment of $2.5 billion – including a $ 243.6 million fine, compensation payments to Boeing’s 737 MAX airline customers of $1.77 billion, and a $500 million crash-victim compensation fund.

Enraged families of victims, when made aware of the leniency deal, said they should have been consulted. They want the agreement thrown out, and Boeing and its high-ranking executives held accountable at a public trial.

“My first reaction was, people were bought off,” said Chris Moore, whose 24-year-old daughter, Danielle, was killed when a 737 Max bound for Nairobi, Kenya, crashed after takeoff in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in March 2019.

“The crash that killed my daughter was the biggest engineering failure of the century — textbook don’t-do-this-ever,” said Moore, who works for the Toronto school board. “And Boeing walked away with an assembly-line type secret agreement and a minimal fine.”

From juvenile justice to corporate crime

Deferred prosecution agreements had a start in Brooklyn in the 1930s as a way to give juvenile offenders a second chance. If the young person successfully completed a rehab program, prosecutors dropped the charges.

In the 1970s, prosecutors sought to ramp up enforcement actions against multinational corporations as part of a wave of post-Watergate reforms. In 1977, Congress passed the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, or FCPA, which outlawed bribes paid to foreign officials, and enforcement began in earnest after an international treaty against foreign bribery was signed in Paris in 1997.

After the savings-and-loan crisis of the 1980s, hundreds of bankers were convicted of fraud and sent to prison. Similarly, after the Enron, WorldCom and Tyco scandals in the early 2000s, their chief executives (among others) were paraded before news cameras in so-called perp walks and ultimately sentenced to lengthy prison terms.

The get-tough approach to corporate crime began to soften in 2002 after accounting giant Arthur Andersen was indicted on federal charges for its role in the Enron scandal. News media at the time called the indictment, which sent customers fleeing, “the death penalty, ” and by the time the Supreme Court, in 2005, overturned Andersen’s conviction, the firm was long gone.

Andersen’s collapse — following its conviction and exclusion from bidding on public contracts — set off a political uproar over what critics denounced as prosecutorial overreach. As a result of the so-called “Andersen effect,” a chastened Justice Department adopted a less aggressive approach to corporate crime. A tool originally designed to help disadvantaged youngsters in Brooklyn was applied to multinational corporations.

From 2002 to 2022, the Justice Department entered into more than 440 deferred prosecution and non-prosecution agreements for bribery and other corruption-related offenses. In the previous two decades, there had been less than a dozen, according to the Corporate Prosecution Registry, an online database created by Duke University’s Brandon Garrett and the University of Virginia’s Jon Ashley.

Under deferred prosecution agreements, prosecutors typically charge the offending company with a crime but agree to drop the charges in exchange for the payment of fines, cooperation and corporate reforms. Sometimes a subsidiary is allowed to plead guilty, allowing the parent company to escape the stigma of a felony conviction.

In a non-prosecution agreement, or NPA, prosecutors agree not to charge a company at all in exchange for financial penalties and cooperation. Typically such agreements aren’t filed in court.

The Andersen effect – the new reluctance of prosecutors to seek indictments and take corporations to trial – became evident gradually. In 2005, KPMG, one of the remaining big accounting firms, admitted to making possible at least $2.5 billion in evaded taxes. Prosecutors called it the largest criminal tax case ever, but they still granted KPMG a deferred prosecution agreement, requiring the firm to pay $456 million in fines, restitution and other penalties and a promise not to break the law again.

Over the next decade and a half, KPMG was sanctioned and reprimanded by at least five countries. In one case, KPMG paid $9.65 million to Dutch authorities to settle charges that it helped a Dutch construction company disguise suspicious payments. Other allegations ranged from altering audits to “grave professional misconduct” to improperly auditing companies under investigation for bribery.

All the while, KPMG continued to win public work in the United States, landing at least $3 billion in federal contracts between 2008 and 2022 – including a lucrative job from the Justice Department.

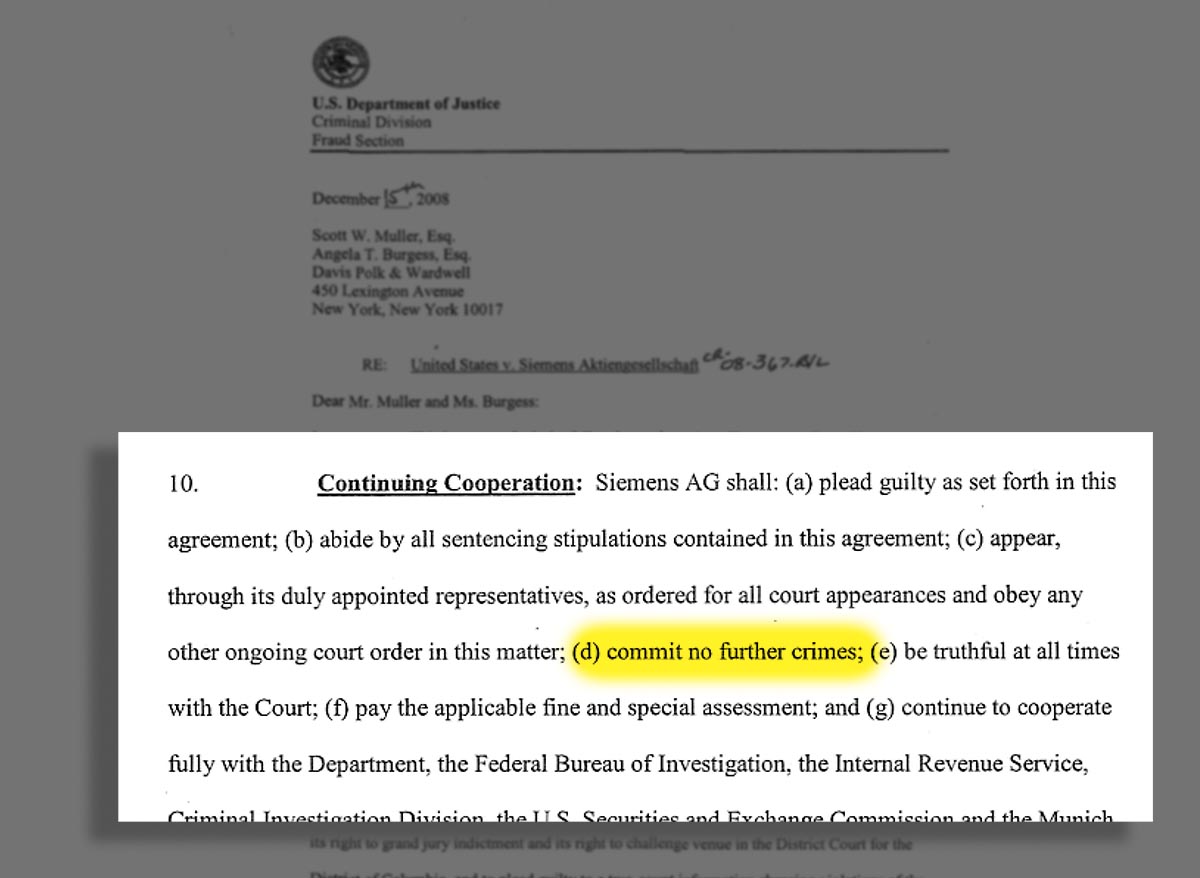

The globalization of corporate leniency deals took off in 2008 when Germany, staggering under a cascade of corruption scandals, teamed up with the U.S. Justice Department to settle bribery charges with Siemens AG. Prosecutors accused the German engineering giant of using slush funds and shell companies to hide 4,000 bribes, totaling $1.4 billion, to win contracts on five continents.

Siemens and subsidiaries in Bangladesh, Argentina and Venezuela agreed to pay $800 million to the U.S. and $813 million to German prosecutors, according to U.N. data. Siemens also agreed to pay $421 million to four other countries — Italy, Switzerland, Nigeria and Greece — and $100 million to the World Bank, the U.N. data show.

The company vowed to commit “no further crimes” and to rehabilitate itself. In return, prosecutors agreed not to use information collected in the investigation in a criminal case.

Solmssen, the American lawyer who supports negotiated settlements, led Siemens through the corruption scandal as its general counsel from 2007 to 2013. He said the firm’s primary objective was to avoid “debarment,” or getting barred from U.S. or European government contracts. “It worked.”

Siemens won $14 billion in U.S. and European government contracts after the 2008 agreements, records show.

Solmssen said Siemens and its subsidiaries spent hundreds of millions of dollars to clean up their leadership culture and went on to improve profitability and gain market share as a result. He added that Siemens’s top rival, GE, claimed it had suffered because of Siemens’s bribery. A GE senior vice president lamented to Solmssen shortly after the settlement: “You guys got away with murder.”

Hailed as a landmark, the Siemens case also revealed a weakness of deferred prosecution agreements as a deterrent to corporate crime.

ICIJ partner Süddeutsche Zeitung later revealed that prosecutors in China had brought dozens of bribery prosecutions against distributors of Siemens medical devices between 2004 and 2014, while the company was negotiating its agreements, and in the years after, while the company was under the supervision of a monitor. The newspaper reported on backdoor deals, including with Chinese hospitals that bought equipment at inflated prices, paid dealers through offshore companies and received bribes for contracts.

Siemens rejected allegations in the German newspaper about improper business practices in China.

In an email, company spokesman Florian Martini said that Siemens has a comprehensive compliance program “subject to continuous improvement” but that even the best system can’t prevent every violation.

Prosecutors and government authorities in several jurisdictions are continuing to investigate Siemens and current and former employees, Martini said. None of these probes, he said, involve allegations that would lead to a breach of the company’s 2008 settlements. “Siemens AG takes all these allegations, investigations and proceedings very seriously,” Martini said.

‘Transactional justice’

In the wake of the 2008 Siemens deal, other countries began to adopt U.S.-style corporate settlements as law enforcement’s fight against corruption intensified across industries and borders. Not only were settlements a way to lower costs of prosecution, but they also headed off what other nations saw as possible U.S. prosecution of non-U.S. companies. Plus, other nations could now get a piece of the financial settlements.

ICIJ’s review found that the number of leniency agreements surged globally over the last 20 years — from just 19 companies paying $57 million to four countries between 2001 and 2005, to 106 companies paying $25.2 billion to 21 countries between 2016 and 2020.

Negotiated corporate settlements gained traction in Europe first, then in South America and Asia. A Japanese version came into effect in 2018. Policymakers in Australia and tiny Jersey, an island in the English Channel, are now considering adopting deferred prosecution agreements. In Argentina and Brazil, prosecutors may now suspend a corporate prosecution in return for a fine.

Even France, which long frowned on what officials call “negotiated justice,” created a “public interest judicial agreement” under a law named for former Finance Minister Michel Sapin.

In an interview with ICIJ partner Le Monde, Sapin said the new policy was needed to give France a chance to prosecute more corporate corruption cases. “It is true that so-called transactional justice is not the French way [but] … we were … in this incredible situation,” he said. “Our companies were [getting] convicted elsewhere and paid their fines elsewhere.”

Now, Sapin said, they can be held accountable efficiently.

France has levied $4.2 billion in sanctions in the six years since the law took effect, records show.

According to ICIJ’s analysis of U.N. data, the highest settlement in a country that offers corporate leniency deals was $2.5 billion in 2020 — ten times as much as the highest settlement payment seven years earlier.

In recent years, House and Senate committees in Congress have questioned negotiated corporate agreements and asked whether Justice Department officials failed to pursue criminal charges against big companies because they were deemed “too big to jail.” Government auditors found that judges simply rubber-stamped the deals, showing that judicial oversight was ineffective.

Critics suggest that the U.S. government views deferred prosecution agreements as a gold mine, and doesn’t want to endanger that revenue stream. Other beneficiaries, they note, include corporate defense lawyers, investigators and court-appointed monitors who supervise companies during probation, collecting millions of dollars in fees for their work.

Walmart, for example, reported spending more than $900 million on internal investigations, compliance and “organizational enhancements” to settle a massive bribery case in 2019 — three times what it spent on penalties and other payouts.

The company has said the money poured into ethics and compliance reflects Walmart’s commitment “to doing business the right way.”

The biggest winners, critics note, are the companies themselves. Walmart was at the top of the Fortune 500 list when it entered into a non-prosecution agreement with U.S. authorities for paying bribes to win store permits and licenses in Mexico, India, Brazil and China. Walmart’s payout was 4% of its 2019 profit.

Justice in the shadows

Negotiations over alleged corporate wrongdoing feature teams of prosecutors and defense attorneys privately thrashing out the details of fines, charges – even the wording of news releases.

This is where the “sausage is being made” for corporate justice, as the WilmerHale law firm put it in a briefing paper for clients.

A German lawyer likened the process to a “Turkish bazaar.”

Typically, the settlement is worked out by like-minded professionals, prosecutors and lawyers for the company, who often used to be prosecutors.

In negotiations, prosecutors might offer “carrots” to encourage companies to voluntarily disclose misdeeds; companies, through their lawyers, might respond by offering to fund expensive internal investigations and creating PowerPoint presentations about kickback schemes. A breakdown in talks might require a late-night crisis-management meeting.

Most deals include a monetary settlement — which could be in the form of fines, charitable contributions, the payment of back taxes or the return of profits from corrupt schemes.

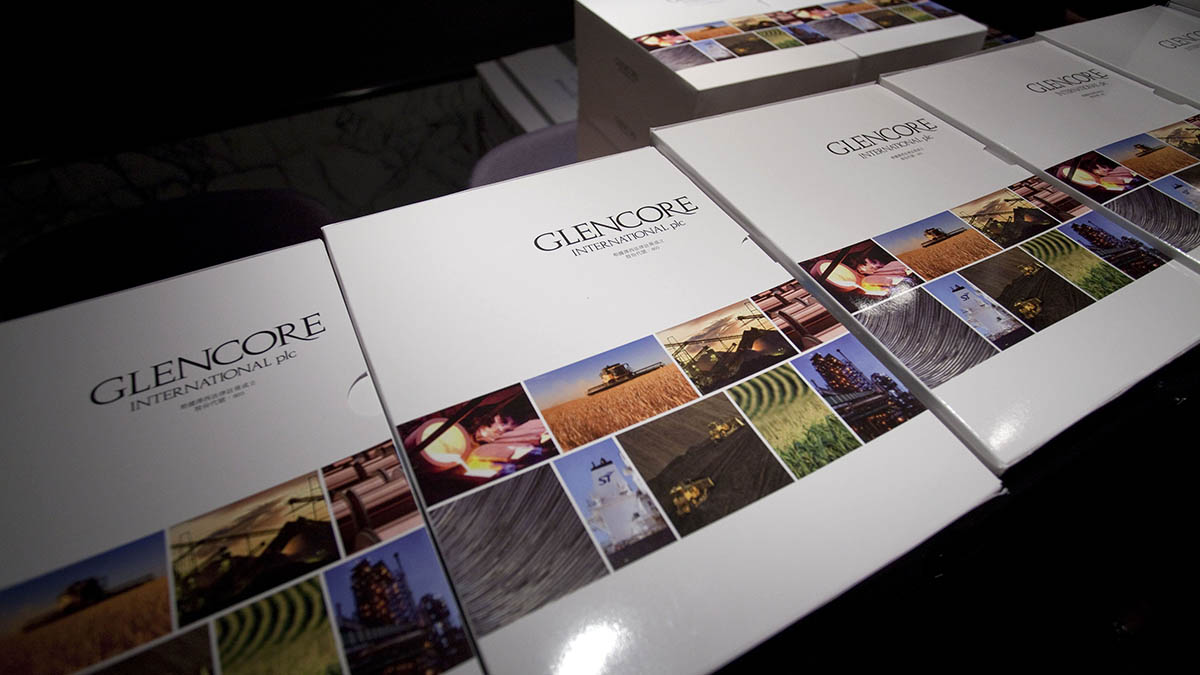

Recently, WilmerHale disclosed details of behind-the-scenes negotiations between a client, commodities giant Glencore International AG, and prosecutors from the U.S., U.K. and Brazil investigating a staggering campaign of bribery across the African continent and in Brazil and Venezuela.

In one case, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Glencore bribed a judge to make a $16 million lawsuit disappear. A doctor and his wife who provided health care to miners and their families had brought the lawsuit after a Glencore affiliate canceled its contracts with their company.

“We have patiently waited for over a decade for justice to be served and to be made whole,” Dr. Ian Hagen said in a victim-impact statement filed in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, where he and his wife Laurethé are seeking restitution.

Glencore pleaded guilty in May and agreed to pay more than $1.1 billion to resolve the investigations. Still the company insisted that it was entitled to a 15% discount on its U.S. fine, noting that it had handed over more than a million documents, named “numerous” culpable individuals “without regard to their seniority,” and made detailed presentations of misconduct, according to a WilmerHale memo to the court.

In many cases, pitched negotiations last years — once up to seven years— with company representatives “heavily editing” the final documents into “an incomplete and much negotiated script,” John C. Coffee Jr., a Columbia University law professor, has written.

So frequently do companies hire former prosecutors or politically connected insiders to conduct the talks that critics have come to describe them collectively as “FCPA Inc.,” after the anti-bribery Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Notable names in the enterprise include Cheryl Scarboro, the former head of the Securities and Exchange Commission’s anti-bribery unit, who went on to represent Ericsson in its corruption case; the late John Ashcroft, a former U.S. attorney general who was paid $52 million as a private monitor for the medical device firm Zimmer Holdings; Louis Freeh, the former FBI director, who served as a monitor for Daimler AG and Walmart and performed internal inquiries for Ericsson; David Gold, a member of the British House of Lords, who served as a corporate monitor of BAE Systems, the U.K. defense contractor; Noëlle Lenoir, a former French junior minister for European affairs, who reviewed an Airbus compliance program; and Theo Waigel, a former German finance minister, who served as a monitor for Siemens.

And then there is Robert Khuzami, who introduced a civil form of deferred prosecution agreement to the SEC while director of its enforcement division. Early in his career, he worked for a U.S. attorney’s office in New York before joining Deutsche Bank as its general counsel. Then he went to the SEC as head of enforcement, moved to a big law firm with corporate clients and returned to the U.S. attorney’s office. He now works for an investment firm.

Tony West, a former U.S. associate attorney general, in July signed a non-prosecution agreement on behalf of Uber Technologies as its chief legal officer. Uber paid $148 million to settle allegations that it deceived investigators about a 2016 data breach affecting 57 million passengers and drivers.

Uber and the U.S. announced the agreement 12 days after ICIJ and media partners published the the Uber Files, an investigation that showed how the tech giant won access to world leaders, deceived investigators and exploited violence against drivers during its chaotic climb to global prominence.

An Uber spokesman said chief legal officer West “never negotiated with or reached out to the DOJ” about the ride-hailing company’s non-prosecution agreement. Other former government officials and insiders didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Officials in Britain, Canada and France argue that their versions of leniency agreements require more court oversight and, thus, offer more transparency than those of the U.S.

“The great fear linked to these transactions is that they give rise to discussions conducted in the shadows,” Sapin, the former French finance minister, told Le Monde. But he added that France requires a public hearing and a judge’s approval of the agreement.

Critics counter that even those countries that handle such agreements more openly don’t disclose much information about the facts of a case and less about behind-the-scenes negotiations that led to the settlement.

ICIJ’s review found that agreements are often made public with just barebones facts, without naming bribe-payers or bribe-takers. In some countries, the agreements are not made public at all.

Auditors for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development who monitor countries’ enforcement activities found scant information on how some prosecutors calculate penalties. In Chile, where prosecutors increasingly settle corruption cases through “conditional suspensions” and “abbreviated procedures,” public documents reveal little about the cases.

German officials provided no information on bribery cases resolved through settlements by “discontinuation” and without a trial. And OECD monitors concluded that German corporate deals are sometimes conducted in an “informal” process with “no concrete and transparent rules” for determining corporate fines.

Transparency International describes corporate criminal negotiations in France as “covered by secrecy,” making it difficult to understand the basis for fines. And the text of settlement deals provides only a “scarcely readable summary” of the allegations.

Of more than 40 countries that said they have negotiated settlements, very few have released the documents to the public, according to a 2018 survey by the International Bar Association.

Switzerland’s Strafbefehl, or summary punishment notices, are posted at a prosecutor’s office for just 30 days, then are taken down and become available only on request.

In Denmark, a court doesn’t review, let alone endorse, settlements. The country’s state prosecutor for serious economic and international crime, known as SØIK, typically publishes only the amount of the fine in a case – nothing more, according to the OECD. The SØIK told the OECD that special agreements are less transparent by design because their purpose is “to end the prosecution in a more silent way.”

In the U.S., considered the gold standard for transparency, Jon Ashley, a law librarian at the University of Virginia, is suing the Justice Department for access to at least a dozen non-prosecution agreements. Justice officials also have withheld monitoring reports about companies’ compliance with settlement agreements. They fought, for instance, against 100Reporters, a news organization seeking the release of compliance reports in the Siemens case.

In the Ericsson case, ICIJ filed a Freedom of Information Act request a year ago seeking access to monitor reports. The Justice Department said the request is pending. On average, the department said, it takes 853 days to process a “complex request.”

A ‘facade of enforcement’

Siemens isn’t the only company that paid to settle bribery or fraud charges and continued to profit from government business.

ICIJ found that at least a dozen large firms profited from U.S. and European contracts after they paid to settle bribery or corruption-related allegations. And often the settlement payments imposed for corruption were a fraction – less than 1% – of the profit that they continued to generate.

One of those was Cardinal Health, a giant pharmaceutical and medical products company based in Dublin, Ohio. In 2020, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission accused the company of failing to oversee a subsidiary that allegedly paid bribes in China. The company settled the case for $9 million. It has since won at least $1.3 billion in U.S. federal contracts.

In 2019, Microsoft’s Hungarian subsidiary entered into a non-prosecution agreement with U.S. federal prosecutors to resolve corporate bribery allegations. The very next year, Microsoft won more than $500 million in U.S. public contracts.

In the two years since Boeing agreed to pay $2.5 billion to settle the 737 Max fraud conspiracy case, it won U.S. and European public contracts totaling more than $39 billion.

“A billion dollar fine to a company making $100 billion means little,” said Coffee, the Columbia University law professor, who is a critic of the deals.

Against the backdrop of press releases hyping record settlements and tough enforcement, financial sanctions in some countries were set lower than the amount of the bribes, according to audits performed by OECD.

The U.N. data shows 177 people settled bribery-related offenses with the Justice Department and federal regulators since 2000 — but only a small number were associated with large, publicly traded companies.

Duke University’s Garrett, author of a book about corporate crime settlements called “Too Big to Jail”, found in his research that most individuals who were prosecuted were middle managers or low-level employees.

In 2015, the Justice Department vowed to renew its emphasis on prosecuting individuals, and recently the department repeated that pledge. Yet since 2015, the Justice Department has charged individuals in only 25% of its 48 corporate anti-bribery enforcement actions, or only one of every four cases, according to an analysis by Mike Koehler, a legal expert who runs the FCPA Professor website. He says the spread of the U.S. anti-bribery model could lead to a “global facade of enforcement.”

ICIJ and its media partners found problems starting to surface. In Belgium, ICIJ’s partner De Tijd found an 11-year-old law allowing plea deals in key criminal cases has faced criticism for lax judicial oversight and fueling “class justice.”’ In Italy, prosecutors acknowledged that maximum fines for companies are too low to serve as a deterrent.

The United Kingdom has yet to convict an individual for misconduct in connection with a corporate deferred prosecution deal, according to Susan Hawley, executive director of Spotlight on Corruption, a U.K. anti-corruption group.

The system allows economic actors to buy their innocence … in a sharp contrast with ordinary justice where individuals routinely face harsh sentences for even less serious offenses. — Jean-Philippe Foegle, case manager at advocacy group Sherpa

In Germany, ICIJ’s partner, paper trail media/Der SPIEGEL, found that prosecutors are resolving serious bribery charges against individuals with an enforcement tool called §153a StPO — originally designed to keep minor offenders like shoplifters out of prison.

In France, “the fines are too low to serve as a deterrent and they rarely cover the full damage inflicted to victims,” said Jean-Philippe Foegle, case manager of the illicit financial flows program of Sherpa, an anti-corruption advocacy group in Paris. “The system allows economic actors to buy their innocence at the expense of the victim’s right to fairly assert their rights, in a sharp contrast with ordinary justice where individuals routinely face harsh sentences for even less serious offenses.”

Repeat offenders

JPMorgan Chase is one of the world’s largest public companies with assets of $2.6 trillion. It is also a poster child for what critics call the corporate repeat offender club, having negotiated deals to settle criminal and civil charges at least four times in the last eight years. Among the deals the bank inked with U.S. authorities was a 2020 settlement in which it admitted to manipulating markets in its trading of metals futures — similar to conduct it had admitted to five years earlier. In all, the bank agreed to pay more than $3.4 billion to settle the cases, amounting to less than 2% of the bank’s profit over that period of time.

Less than a year later, while still under the U.S. deferred prosecution agreement, JPMorgan entered into a negotiated settlement with French authorities to resolve allegations of tax fraud.

When it comes to white-collar recidivism, it’s hard to top Deutsche Bank. Among the numerous civil and criminal charges brought against it by U.S. authorities: misleading borrowers and investors in the run-up to the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, helping clients evade taxes in 2010, manipulating its benchmark interest rate in 2015,and corruptly hiring sons and daughters of officials of foreign governments and state-owned enterprises in 2019. The bank also agreed to pay $150 million for failing to monitor the financial dealings of registered sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, and then, in 2021, $130 million for concealing bribes to win business in places like Saudi Arabia and Italy and for other alleged crimes.

The first time Zurich-based ABB Ltd. settled a bribery case was in 2004, after U.S. prosecutors accused the tech company of improper conduct in Nigeria, Angola and Kazakhstan. The second time, in 2010, was in connection with the U.N. Oil for Food program in Iraq. The third settlement was announced this month by authorities in South Africa, the United States and Switzerland. ABB admitted that, through subsidiaries, it had bribed a high-ranking employee at South Africa’s state-owned energy company to win contracts. An action is pending in Germany.

“We have a clear zero tolerance approach to non-ethical behavior within our company,” ABB CEO Björn Rosengren said in a statement.

Last month, in France, European aerospace giant Airbus SE agreed to pay $16.4 million to settle bribery probes in Libya and Kazakhstan – on top of a $3.9 billion deal it signed in 2020.

“The company has taken significant steps since 2016 to reform itself,” Airbus said in a statement, “underpinned by an unwavering commitment to integrity and continuous improvement.”

ICIJ’s review shows misbehaving companies have signed negotiated agreements, sometimes overlapping the same time periods, with different countries, including in the U.S. and France. Credit Suisse, one of Europe’s largest banks, agreed to pay $2.6 billion in 2014 to settle charges of helping Americans evade U.S. taxes.The bank agreed to “close any and all accounts” of those resisting to disclose their ownership.

Two months ago, Bloomberg News reported that the Justice Department was investigating a whistleblower’s claims that Credit Suisse hadn’t in fact closed all the accounts and that it violated its plea agreement. The report came days before the bank agreed to pay France $234 million to avoid prosecution in a separate tax fraud and money laundering case.

Those troubles were preceded by an October 2021 deferred prosecution agreement between the bank and U.S. authorities over fraud charges in yet another case. And before that, Credit Suisse had reached a $117 million agreement with Italian authorities in 2016 and agreed to pay $205 million to settle in Germany in 2011 – both over allegations it helped clients dodge taxes.

Sapin, the former French minister, says Credit Suisse and other companies don’t count as recidivists because they didn’t commit the same crime twice – in France. “It is true that names appear repeatedly in cases and that there can be a certain permanence in corruption,” Sapin said. “But this is not the case in France,” Sapin said, adding that recidivists don’t qualify for leniency deals.

Globally, governments also have rewarded corporations with second negotiated agreements that are at times more lenient than the first settlement.

In 2020, without admitting or denying wrongdoing, Italian energy giant Eni agreed to a U.S. civil order not to violate anti-bribery accounting rules – the same rules it had agreed not to violate a decade earlier. The first settlement concerned bribery allegations in Nigeria by a then-Eni subsidiary; the second, in Algeria, occurred after another Eni-controlled subsidiary entered into sham contracts to disguise bribes as legitimate fees, a way to help win oil contracts.

“Eni is a recidivist,” the SEC said in a press statement announcing the 2020 order.

In what one legal expert called “a seemingly lenient settlement,” financial regulators ordered Eni to pay a $24.5 million disgorgement of ill-gotten proceeds, saying the oil company had cooperated in the investigation. Italian courts had earlier acquitted Eni and its subsidiary in the Algeria case, and the company proclaimed its innocence.

Last year, Eni struck a separate settlement with Italian authorities, this time in a graft case in the Republic of Congo. Eni agreed to a reduced charge of “undue inducement” and agreed to pay a small fine of $975 million, plus $12.9 million confiscated as illegal profits from bribery. In a report in October, OECD monitors criticized the terms of the agreement because the bribes were valued at $77 million while the licenses obtained through the bribery were worth nearly $1 billion. The judge ruled the sanctions appropriate because Eni had, among other things, tightened its compliance programs.

In an email to ICIJ, Eni spokesman Roberto Albini denied the bribery accusations. He said the Nigeria case was about Eni’s former subsidiary and that the company made “no admission to bribery in Algeria.” As for the Republic of Congo case, Eni agreed only to a lesser non-bribery charge, Albini said.

“The relatively nominal amount of the agreed sanction clearly explains by themselves that there was no material case,” he said, adding that the charges brought by prosecutors and activist media were “clearly grossly overrated and wrong.”

ICIJ’s review shows that at least 10 of the world’s top drug and medical devices companies are repeat offenders, having settled corruption-related charges at least twice each. Novartis, the Swiss drug giant, settled accusations that it paid bribes or kickbacks to doctors and hospitals at least four times.

In 2010, a Novartis subsidiary in the U.S. agreed to pay more than $422 million in criminal and civil penalties to resolve charges it had illegally marketed the anti-seizure medicine Trileptal and five other drugs. Prosecutors also accused the company of paying kickbacks to health care professionals to induce them to prescribe the Novartis drugs.

“Sanctions were generally mere slaps on the wrist,” the Justice Department wrote in 2013 when it filed a new complaint against the company, acknowledging the earlier penalties didn’t stop the kickbacks. “Novartis continued to conduct bogus speaker programs that were simply vehicles for paying kickbacks to doctors in the form of honoraria and expensive meals.”

Two years later the company agreed to pay $390 million to settle a new case brought by the Justice Department. Novartis also agreed to extend a five-year corporate integrity agreement that it had signed in 2010, pledging again not to violate anti-kickback laws. In 2020, the firm signed yet another five-year integrity agreement in which it promised not to pay kickbacks.

Novartis would go on to pay $25 million in 2016 to resolve a civil case alleging its China subsidiaries made improper payments to Chinese health care providers to win sales. The subsidiaries paid for, among other things, gifts, sightseeing trips, spa and sauna sessions, “walking around” money and cover charges at a strip club. The next year, South Korea fined the drugmaker about $49 million for offering kickbacks to doctors there.

In 2020, Novartis agreed to pay $591 million to settle Justice Department civil claims that it paid kickbacks to U.S. doctors to induce them to prescribe Novartis drugs.

Novartis’ Greek subsidiary and a former affiliate agreed to pay $233 million to avoid U.S. prosecution on charges of bribing health care providers in Vietnam and Greece to buy eye medications and artificial lenses. And the parent company agreed to pay $112 million to settle civil charges that it violated accounting provisions of the U.S. anti-bribery law while doing business in South Korea, Vietnam, Greece and China.

The U.S. allowed the Greek subsidiary to sign a three-year deferred prosecution agreement and pay a fine on the lower end of the sentencing guidelines, citing its “full cooperation.”

In turn, Novartis executives promised to live up to the company’s values and make a clean break from the past.

Contributors: Nicole Sadek, Brenda Medina, Maggie Michael, Spencer Woodman, Ben Hallman, Dean Starkman, Richard H.P. Sia, Emilia Díaz-Struck, Lars Bové, Guilherme Amado, Zach Dubinsky, John Hansen, Anne Michel, Adrien Sénécat, Frederik Obermaier, Bastian Obermayer, Marvin Milatz, Friederike Röhreke, Ruben Schaar, Leo Sisti, Paolo Biondani, Karlijn Kuijpers, Fredrik Laurin, Christian Brönnimann, Jiyoon Kim, James Oliver