The U.S. Treasury Department’s quest to build a company ownership database meant to battle dirty money has hit another setback, with a key national banking group calling for the agency to withdraw its “fatally flawed” plan.

In a letter submitted last week, the American Bankers Association said the Treasury’s latest proposed rule for the registry would so sharply restrict bankers’ access to company ownership data that it would be useless to the country’s sprawling financial sector.

The industry association’s comments, co-signed by 51 state-level banking associations, are a stark reversal for a group that had previously been a key supporter of the law mandating the database’s creation. The group’s comments do not question the overall registry but rather focus on the Treasury’s plan for implementing it.

Experts say the creation of a registry of company owners is crucial for unmasking the people behind anonymous shell companies that criminals and terrorists use to hide and transfer illicit cash. Advocates have consistently flagged the U.S. financial system as notoriously opaque and vulnerable to money laundering.

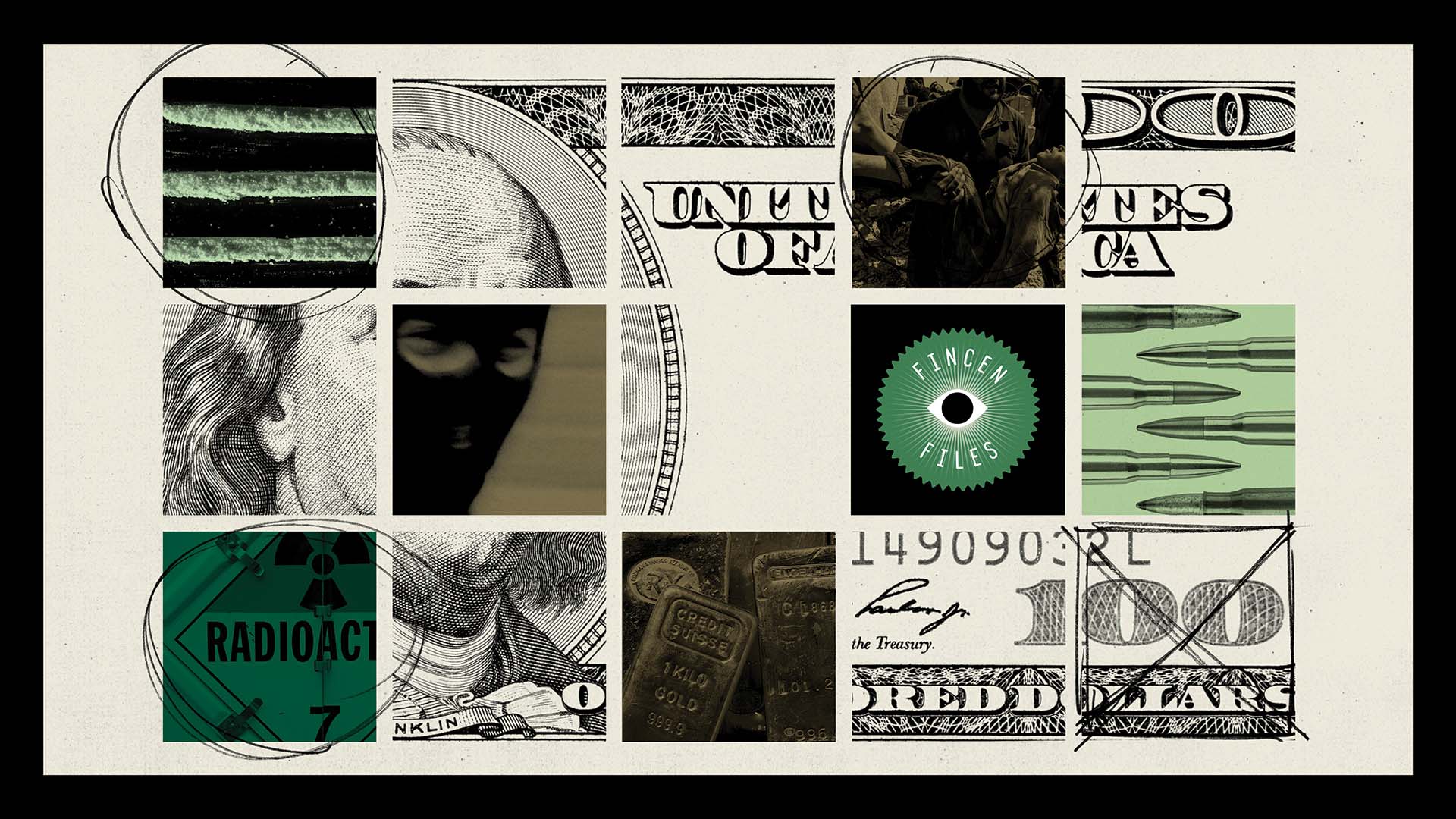

In September 2020, ICIJ, BuzzFeed News and more than 100 media partners published the FinCEN Files, exposing more than $2 trillion in suspicious transactions flowing through the global financial system via U.S.-based banks.

Citing public outcry following the FinCEN Files’ release, U.S. lawmakers advanced a landmark anti-money-laundering bill called the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020, which included the Corporate Transparency Act. The law tasked the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network — FinCEN — with setting up the new database and writing the detailed regulations that would undergird the system.

The American Banking Association had originally hoped that a reliable ownership database would reduce burden on bank staff in performing due diligence to ensure clients are not moving dirty money through company accounts. But the Treasury Department’s latest proposal would require bankers to ask for a client’s consent to seek their information in the database. Once a client approves, the bank would also have to submit a request to be reviewed by Treasury Department officials each time they wanted to access ownership information. The banking association said the proposed set-up would be “so limited that it will effectively be useless.”

Ross Delston, a Washington, D.C.-based attorney and anti-money laundering specialist, told ICIJ that requiring bankers to attain customers’ consent before accessing ownership data is one of the most egregious flaws of the Treasury’s proposed management of the database.

“This can only be thought of as an attempt to limit the utility of the registry and is not found in any of the registries around the world that are actually useful, and publicly accessible,” Delston said.

Bankers are not the only proponents of the Corporate Transparency Act who have expressed concerns about the implementation of the law. Transparency activists criticized the government for exempting certain investment vehicles and forbidding the public from accessing the database – a restriction that was mandated in the law itself.

Both bankers and transparency experts also worry that the ownership data, regardless of whom it is shared with, may be of limited value because the government may do little to verify the accuracy of the information it collects. In a recent letter submitted to the Treasury, advocacy group Transparency International urged the department to use the government’s vast existing stores of data for quality control on the ownership information it receives.

The group cited the United Kingdom as an example, which, after years of neglecting to verify ownership information in its own public registry, has now made an about-face. “The UK is now moving to verify reported information,” Transparency International said, “and the U.S. must learn from their experience by doing the same.”