IMPACT

Where are the key Panama Papers figures, seven years later?

On the seventh anniversary of the Panama Papers, here’s an update on where some of the most pivotal figures are now, and the legacy the investigation left behind.

Seven years ago today, more than 370 journalists at over a hundred publications around the world simultaneously published the Panama Papers investigation with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

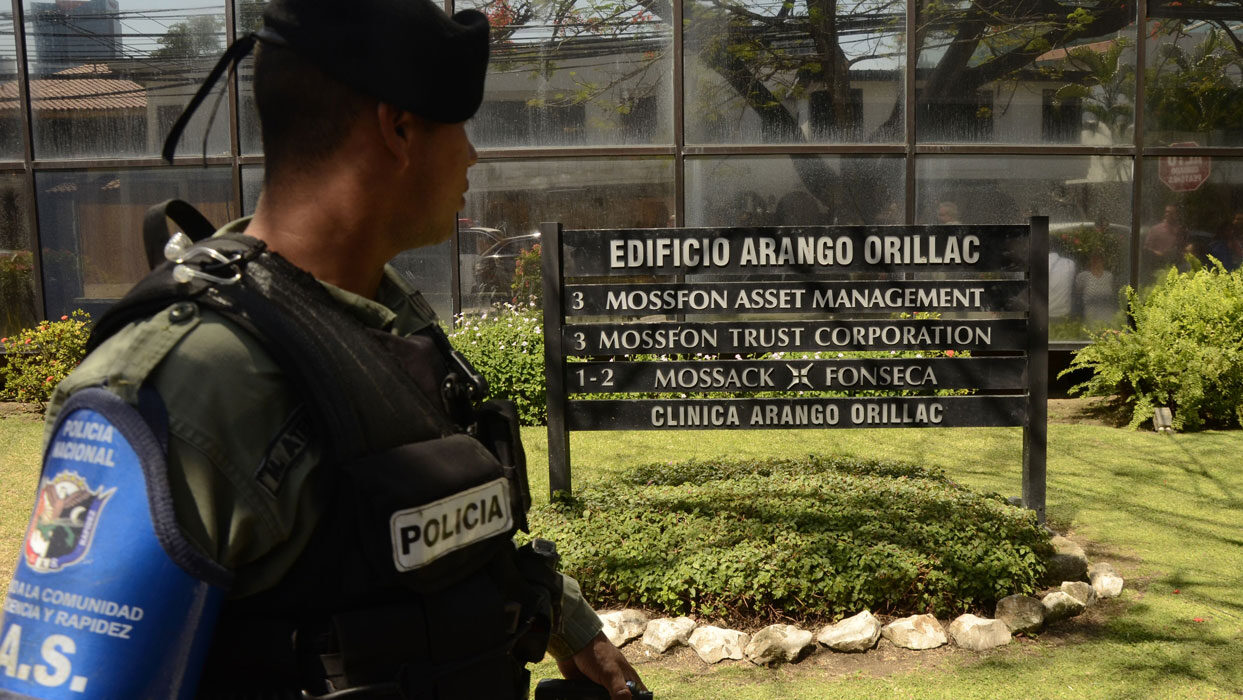

The Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation was based on a leak of millions of documents from a Panamanian law firm, Mossack Fonseca. The cache of files, first obtained by reporters with German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared with ICIJ, included details on the financial secrets of 140 politicians and countless other celebrities and business owners around the world, and revealed how they moved their money through a secretive parallel economy based in offshore tax havens.

On the seventh anniversary of the Panama Papers’ release, here’s an update on where some of the most pivotal figures of the original investigation are now, and the legacy the Panama Papers left behind.

Mossack and Fonseca

The now infamous Panamanian law firm and target of the leak, Mossack Fonseca, closed within two years of the investigation’s release, buckling under lawsuits and global pressure. However, the eponymous co-founders of the company, Ramón Fonseca and Jürgen Mossack, are reportedly still in Panama, according to ICIJ member Sol Lauría Paz.

While Mossack is lying low, Lauría Paz says, Fonseca is active on Twitter, where he posts several times a day, often touting conspiracy theories about the Panama Papers and COVID-19.

The pair were acquitted in a Panamanian money laundering case in 2022, after the judge ruled the prosecution failed to prove the firm handled or tried to hide illicit funds from Brazil. The two lawyers are, however, among dozens of defendants in a second case related to the Panama Papers for “crimes against the public economic order.” A hearing date is set for December 2023.

The two are still being sought by German prosecutors, but are protected from extradition by a Panamanian constitutional protection.

Mossack and Fonseca haven’t just been on the receiving end of lawsuits — in 2019, they launched a legal suit that attempted to block the release of “The Laundromat,” a Netflix film inspired by the Panama Papers, arguing that their depiction by Gary Oldman and Antonio Banderas was defamatory. They didn’t win.

Icelandic PM Gunnlaugsson

One of the most immediate and visceral reactions to the Panama Papers came in Iceland, where then-Prime Minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson resigned after documents revealed that he held an offshore company used to shelter money — and hadn’t disclosed it. After two days of public backlash, Gunnlaugsson stepped down and was replaced by Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson.

Gunnlaugsson did mount a political comeback — in 2017, he established the conservative Centre Party, and he continues to serve in Iceland’s parliament as the party’s leader.

In 2018, though, Gunnlaugsson found himself at the heart of a second scandal — the Klaustur Affair — when a leaked recording captured him and other officials talking about female colleagues, including a disabled woman, in a disparaging sexual manner. Gunnlaugsson reportedly apologized for his part in the scandal.

Pakistani PM Nawaz Sharif

The then-prime minister of Pakistan, Nawaz Sharif, met a much slower political downfall after the Panama Papers, with the investigation revealing his family’s offshore assets and sparking widespread protests and an official probe into Sharif’s finances.

Ultimately, Sharif was disqualified from the prime ministership, sentenced to 10 years in prison, fined $10.6 million and banned from holding public office for life. He’s in self-imposed exile in London, after he failed to return to Pakistan following a trip to the United Kingdom on medical bail. He was recently spotted entering London’s luxury stores.

But there are murmurs, ICIJ member Umar Cheema said, that Sharif may soon return to the country to bolster his political party, which he’s still aiding from afar. The country is due to hold its next general election some time this year.

“His party is in dire need of him ahead of elections, because they think that without him, they may not be able to win,” Cheema, who reports for Pakistani outlet, The News, said. “So they want him in the field.”

Part of the legacy left by the Panama Papers, Cheema says, is how conversations about corruption were so quickly politicized in the country’s ultra-polarized climate. Even holding the Sharifs accountable, which he’d hoped would be a victory of the investigation, was tainted by the lack of truly independent institutions, he said.

“The entire process was muddled and [that] made it so ugly and controversial that sometimes [the legal process] becomes very difficult to defend,” Cheema said.

Putin’s pals

Some of the most complex connections unveiled by the investigation came from a sprawling network of wealth moved around in accounts held by some of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s close allies and friends — money that likely belonged to Putin himself.

The investigation flagged a number of his closest confidants, including classical cellist Sergei Roldugin — a childhood friend of Putin’s. Leaked documents showed that Roldugin was a major figure in a network that moved over $2 billion through banks and shell companies.

Earlier this year, Swiss prosecutors charged four banking executives for their role in helping move millions of those dollars, and failing to flag warning signs about the likely true owner of the accounts. Last week the bankers were convicted and fined hundreds of thousands of Swiss francs.

Roldugin and a number of Putin’s Panama Papers pals have also been on the receiving end of sanctions from the U.S. and other states for their connection to Putin during the war in Ukraine.

The tipster John Doe

The anonymous source that leaked the 2.6 terabyte cache of documents, John Doe, says he still lives with fear for his safety, years after the investigation came out.

“It’s a risk that I live with, given that the Russian government has expressed the fact that it wants me dead,” he told German news outlet DER SPIEGEL in 2022 in his first media interview since the investigation was published.

The leak led authorities to launch hundreds of investigations across the world and sparked the disclosure and investigation of other documents, like the Paradise and Pandora Papers, which uncovered even more about the offshore world.

“The fact that there have been subsequent journalistic collaborations of similar scale is also a real triumph,” Doe said. “Sadly, it is still not enough. I never thought that releasing one law firm’s data would solve global corruption full stop, let alone change human nature. Politicians must act.”

Tax havens’ claims of reform

The uproar over the Panama Papers led to a push to reform tax havens and systems across the globe — a movement that has made some rocky advances in the past seven years.

“While there have been other, and even bigger leaks, the ICIJ’s release of the Panama Papers remains a pivotal moment,” said economist Alex Cobham, who leads advocacy group the Tax Justice Network.

“There had never been such a powerful, public demonstration of the global reach of financial secrecy, and of the tax abuse it facilitates. The Panama Papers gave major momentum to a series of national and international policy processes.”

In Panama itself, for example, the government has since made it mandatory for law firms to identify and verify the ultimate beneficial owner they’re working with, and required the Panamanian tax authorities to share tax information of foreign citizens with their country of origin, among other changes.

While there have been other, and even bigger leaks, the ICIJ’s release of the Panama Papers remains a pivotal moment. — Alex Cobham, Tax Justice Network

The British Virgin Islands — home to the largest number of offshore companies mentioned in the Panama Papers — passed a 2017 law that requires offshore service providers to report the real owners of companies to the Islands’ authorities — though that information is still not available publicly. In the U.S., efforts by the Treasury Department to establish a company ownership database are underway, but have faltered in recent months.

While significant steps — and many loud proclamations — have been made, there remains a long way to go and many hurdles to cross in the push for more transparency in the global financial system. In Europe, for instance, several ownership registries in Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands were recently rolled back, after a European Union court ruled that a public Luxembourg registry violated business owners’ privacy and potentially put them in harm’s way.

Cobham, of the Tax Justice Network, points towards efforts at the United Nations to develop an equitable international tax framework as an example of potential reforms that are promising, but face resistance.

“The pushback from the enablers of abuse has also been strong,” he said. “Much remains to be done.”