TRAFFICKING INC.

Philippine lenders and labor agents fleece workers seeking overseas jobs, interviews and confidential documents show

Domestic workers hoping to improve their lives overseas risk exploitation and abuse. Many end up burdened with crippling debts owed to recruiters, go-betweens and traffickers.

Employment agencies and loan companies in the Philippines have worked together to cheat thousands of women seeking domestic worker jobs overseas in schemes that combine labor exploitation and predatory lending, interviews with workers and thousands of pages of confidential complaints filed with Philippine authorities show.

These companies play on workers’ hopes for better lives for themselves and their families, pressuring them into paying illegal recruiting fees and taking out loans with interest rates often exceeding 130%, workers and complaint documents allege.

These Philippines-based labor firms tell job seekers they can’t get coveted positions as household workers in Hong Kong or Taiwan unless they pay fees ranging between $800 to $1,700, according to interviews with 15 workers. Those fees represent huge sums for workers from impoverished backgrounds. They are also illegal under Philippine law, the complaint documents allege.

To make sure they collect their money, the workers and documents say, employment firms steer workers to lenders that advance them money to cover the hefty fees. The interviews and documents reveal that these lenders promise low interest rates but the actual interest charges are much higher — with annual interest rates ranging between 61% and 578%. Those rates are far above the Philippines’ 8% per year legal limit on what lenders can charge on loans to overseas workers.

The recruiters and lenders pull off the schemes, the documents and workers allege, by rushing workers through a smoke-and-mirrors process that hides key details about their employment and loan contracts. The complaints say some lenders blackmail borrowers by coercing them into signing over blank checks — and then threatening to “bounce” the checks and file criminal charges against them if they complain to government authorities or don’t keep up with their payments.

“I’m so afraid of that blank check, because maybe one day they arrest me because of that,” said Merry Criz Renayong, whose loan with a Philippine lender carries an interest rate of more than 180%. “I’m so afraid I might go to jail.”

I’m so afraid of that blank check, because maybe one day they arrest me because of that. I’m so afraid I might go to jail.

— Merry Criz Renayong, a Filipina worker who took out a high-interest loan

In a nation where poverty pushes as many as one in 10 adults to seek employment abroad each year, the money overseas workers send home helps their families survive, boosts the Philippine economy and earns them praise as “modern-day heroes.” But their financial needs and uncertain immigration status when they go abroad leave them vulnerable to mistreatment not only by employers but also by recruiters and lenders, workers and labor experts say.

“Of course, we want to work abroad, so they charge workers huge amounts of money,” said Annabelle Gutierrez, 38, who described paying a large recruiting fee with a high-interest loan from a lender she’d been directed to by an employment agency. “We grab it because we don’t have a choice.”

Crippling debts

This article is part of a reporting collaboration organized by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Trafficking Inc. ICIJ, The Guardian, NBC News, Reuters and other media partners are examining human trafficking and labor abuses in many parts of the globe.

This story is based on interviews conducted by ICIJ over several months as well as complaint documents obtained by ICIJ that total 2,741 pages and name 12 licensed loan companies operating in the Philippines. The complaints were filed in 2020 and 2021 with at least 10 Philippine government entities, including the country’s Securities and Exchange Commission and Presidential Anti-Corruption Commission.

The complaints were prepared by Migrasia, a Hong Kong-based non-governmental organization run by legal scholars and researchers who focus on issues related to migrant workers throughout Asia.

The complaints have not been previously reported on by news outlets. Officials with Migrasia said collusion between labor firms and lenders has been going on for many years, but their working relationships have never been the subject of wide public exposure.

The choreographed double dealing alleged in the interviews and the complaints provides a fresh example of the kinds of traps and hazards that workers from around the world face when they leave their home countries and seek opportunity elsewhere.

A lack of action by authorities in their home and destination countries leaves workers who cross national borders at the mercy of players who don’t have their best interests in mind. These workers are often burdened with crippling debts owed to recruiters, go-betweens, traffickers and others involved in their journey to what they hope will be better lives.

Along with alleging illegal tactics by lenders and recruiters based in the Philippines, the complaint documents criticize Philippine authorities for failing to crack down on the firms’ practices.

A 2020 filing with government agencies said “little progress has been made” in fighting these schemes despite “numerous complaints made across several months” to the Philippines SEC, whose authority includes regulating consumer lenders.

“The SEC has merely acknowledged receipt of the complaints and has not made any attempt to follow up on the substance of the complaints,” the document asserted.

A 2021 filing naming multiple employment agencies said the Philippine government had failed to even issue warnings to these companies and other labor firms despite “overwhelming complaints and evidence verified by numerous independent parties.”

In a written statement provided to ICIJ, Migrasia said the problem has continued to increase in recent years.

“We hope that authorities in the Philippines and Hong Kong start to take these issues more seriously and listen to community leaders and experts so that they can permanently eliminate these illegal fees and debts from arising,” the statement said.

Borrowing trouble

In October 2019, Merry Criz Renayong left her hometown of San Jose and headed to Manila, the capital of the Philippines.

If she could persuade an employment agency in Manila to get her a job as a housemaid for a good family in Hong Kong, she thought, she could make more money than she was earning in San Jose waiting tables. She could send money home to her family. And she could save enough to send her son and daughter to college, helping them fulfill their dreams of becoming flight attendants.

In a third-floor office in a concrete building along downtown Manila’s United Nations Avenue, staffers with Rapid Manpower Consultants, a recruitment agency licensed by the Philippine government, told her she needed to pay nearly $1,200 to secure a position in Hong Kong, Renayong said in an interview with ICIJ.

Recruitment agencies in the Philippines are prohibited from charging placement fees to applicants seeking domestic worker jobs abroad. But migrant workers can be charged for mandatory training and medical exams under Philippine law and experts say they are often overcharged by agencies seeking to pass their recruitment costs on to the workers.

When Renayong told staffers at Rapid Manpower that she couldn’t pay what the labor firm was demanding, she says, they had a solution — they led her outside the building and around a corner to the offices of Hoya Lending Investor Corp.

Hoya, she says, offered her a loan that would cover the fees demanded by the recruiter and told her the loan contract carried a low interest rate. But she says they wouldn’t give her a copy of the contract she signed, snatching the original away when she tried to take pictures with her phone.

A complaint document prepared by Migrasia said Hoya “generally refuses” to provide borrowers with their loan contracts and other required disclosures, telling them that they can have a copy of their contracts only after their loans are fully paid. During this process, the complaint said, borrowers “are under extreme stress” and “are unable to ask questions or make informed choices” because they know that if they don’t comply, the employment agency working in collaboration with Hoya would block their chance at getting a job in Hong Kong.

After she finished signing the loan documents, Renayong says, Hoya staffers took her to a bank on a different floor of Hoya’s building and helped her set up a checking account. Then, she says, they had her sign a blank check and told her that if she was late with a payment, they’d cash the check for the whole amount she owed — a move that could overdraw her account and lead to criminal charges against her under the Philippines’ “bouncing check” law.

It wasn’t until she started her new job in Hong Kong, she says, that she learned the loan contract required her to pay the lender $365.41 a month — more than three-fifths of the monthly wages she was going to earn in Hong Kong.

The actual annual interest rate on the loan was 188%, according to calculations by ICIJ and the Center for Responsible Lending, a U.S.-based non-profit that monitors high-cost loan products. Hoya charges an average interest rate of 143%, according to a sample of loans reviewed by Migrasia.

The dream job Renayong went into debt for didn’t last. Her employers in Hong Kong, a three-generation household, complained about how she cooked chicken and about the make-up and hair products she wore inside the house, she says. They let her go after three months.

She couldn’t afford to pay another fee to get a job with a different employer in Hong Kong and had no way to keep up with her payments to Hoya, she says. She found a job as a domestic helper in Qatar without having to pay a placement fee. She worries about what Hoya Lending will do when she comes home to the Philippines after she completes her Qatari labor contract in August.

“I’m trying to earn to pay them back in case they file a legal case against me,” she said.

Rapid Manpower did not respond to multiple requests for comment, and when reached by phone, Hoya declined to comment on the allegations.

Powerful connections

The links between Philippine labor firms and lenders go beyond informal working arrangements. The 2021 complaint that names several employment agencies said the Philippine government has allowed “very powerful families” and a “circle of friends” to own or control multiple companies that work in concert to shake down these workers.

In one example, the complaint alleged, a recruiting firm called A&W International Manpower Services Specialist also controlled two lenders — PJH Lending Corp. and Prosperity and Success Lending Investor Corp. — as well as medical diagnostic and training centers and other ventures that profit from migrant workers’ efforts to gain employment overseas.

Gutierrez, the 38-year-old Filipina worker, said in an interview that after she applied with A&W for a household worker position in Hong Kong, the recruiting agency told her she needed to take out a loan with Prosperity and Success Lending to cover more than $900 in fees.

To stop her from looking elsewhere for a loan, she says, A&W’s staff demanded she turn over her identification papers, including her passport.

“I was telling them I wanted to take the loan from another lending company, but they held my documents until it was time for me to fly,” she said. “They forwarded my documents to the lending company, and the loan was ready before my flight.”

Gutierrez and 12 other borrowers interviewed for this story say they felt misled about the costs of their loans, because their lenders falsely promised low interest rates or withheld information about the rates they’d be paying.

A complaint document said loans made by Prosperity and Success Lending generally carried annual interest rates that were “around 90% and often exceeding 100%.”

Gutierrez is from Tarlac City, in a region of the central Philippines known for its vast sugar and rice plantations. Like many others, she said, she has no way to earn an adequate living unless she can work overseas.

In addition to being told to sign blank checks, she says, Prosperity and Success Lending also required her to appear in a video stating she owed $900 to the lending firm.

“I was nervous about getting on the plane to Hong Kong because I was thinking what if my job is not okay, then they would spread that video,” she says.

A&W did not provide a response to ICIJ’s requests for comment. Prosperity and Success Lending declined to comment.

Poverty and Hope

More than 18% of the population of the Philippines are unable to meet their basic food and non-food needs, pushing millions of Filipinos to leave the country to find better jobs and better wages. A recent survey found that 7% of Philippines households have a member working overseas and 7% of adults still living in the country say they’re seeking jobs overseas.

The money overseas workers send back is a vital driver of the country’s economy. In 2022, Filipinos working overseas sent home a record $36.1 billion in cash remittances, accounting for about 9% of the gross domestic product. Social and political reformer Corazon Aquino popularized calling the nation’s overseas workers “modern-day heroes” during her term as president of the Philippines from 1986 to 1992.

There are hundreds of thousands of foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong, mostly from the Philippines and Indonesia. Household jobs involving cooking, cleaning and caring for children in Hong Kong are coveted by Filipinos because there’s a relatively generous minimum wage of more than $600 a month, and the treatment of household workers is more regulated than in other common employment destinations, such as the Persian Gulf countries. In Hong Kong, the law requires that they get a day off each week, a rarity for domestic workers in the Middle East.

Despite Hong Kong’s draw, human rights groups say exploitation and abuse of foreign household workers in the Asian metropolis is all too common. In a 2019 survey of Hong Kong domestic workers, 15% said they had been physically abused during employment. Hong Kong media highlighted concerns about heavy debts owed by domestic workers after three Filipino household helpers died in debt-related suicides in early 2016 and again in 2020 when local police announced they’d busted a “loan shark syndicate” preying on Filipina domestic workers.

An Amnesty International report submitted in January to the United Nations said Hong Kong’s policies on domestic workers’ immigration status and living conditions leave them vulnerable to exploitation by their employers and job-placement firms. The report noted that migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong are “commonly heavily indebted” due to “excessive and illegal” fees charged by employment agencies.

In response to questions from ICIJ, Hong Kong’s Department of Labor said it “does not tolerate any exploitation or abuse” of foreign household workers. On the issue of debt, the agency said it works to help them “carefully assess their repayment ability when taking out loans.”

Fear and intimidation

When workers are unable to keep up with their loan payments, harassment and intimidation by lenders and debt collectors is common, according to interviews and the complaint documents.

Hoya, for example, reveals photos and full names on Facebook of borrowers who have missed payments, according to posts viewed by ICIJ and a complaint document focusing on Hoya. The lender also suggests online that it will file criminal charges against borrowers who fall behind, even though it isn’t a crime in the Philippines.

One post recently visible on a Hoya Facebook page displays copies of two arrest warrants with the names of the persons being arrested covered up.

“Two new love letters[s],” the post says, along with a toothy smiley face emoji. It says the warrants are “for those who don’t want to talk to us and continue to not know how to pay voluntarily. Don’t be surprised if you get one of these.”

One of the complaint documents crafted by legal experts at Migrasia charges that Philippine authorities have allowed Hoya to abuse the criminal court system by fabricating “bouncing check” cases against borrowers. The document alleges that the lender “works with complacent prosecutors and known to be favorable judges in order to fabricate these cases by confiscating bank checks, colluding with bank staff, and conspiring with members of the judicial system.”

The complaint said it’s estimated that more than 60 borrowers are arrested and prosecuted each year in the Philippines by lenders that abuse the judicial system as a tool for collecting predatory debts.

The Philippines Securities and Exchange Commission did not respond to multiple requests for comment. The Philippine government’s Department of Migrant Workers, which is responsible for the protection of the rights and promote the welfare of overseas workers and their families, also did not provide a response to the allegations presented to it by the ICIJ.

Another Manilla-based lender, CASH4U, tried to blackmail victims into making payments by threatening them with criminal charges and impersonating law enforcement, a borrower’s affidavit and two complaints Migrasia filed with Philippine authorities alleged.

A July 2020 complaint prepared by Migrasia claimed CASH4U representatives “falsely threatened borrowers that legal action will be taken, despite acting illegally themselves.” The complaint said CASH4U also threatened that a partner company in Hong Kong would send a “demand letter” to a borrower’s employer — a move that would violate the borrower’s privacy and put them at risk of being fired from their job and sent home.

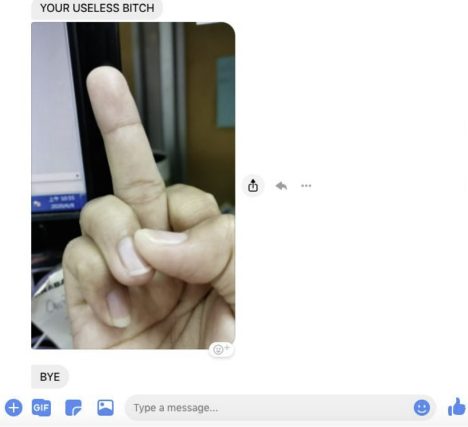

Another complaint filed a month later included a screenshot of a message that it said CASH4U had sent to a borrower with this epithet: “YOUR [sic] USELESS BITCH.” It was accompanied by a photograph of a CASH4U staffer’s middle finger. According to the complaint, CASH4U sent another borrower a threat of legal action that will “greatly affect your local or international employment in the future.”

One CASH4U borrower, Venus Macaraeg, claims that the lender hounded her for more money even though she’d repaid the loan, plus interest, forking over more than $1,200.

“They would not explain why I owe additional money,” she said in an interview. “They said that if I did not pay the penalty interest, I would be subject to a criminal investigation or blacklisting from working in Hong Kong.”

A former director of CASH4U told ICIJ that the company was put out of business by the pandemic, but it has outsourced its debt collections to a collection agency.

Fighting back

Macaraeg hasn’t been able to see her own child for five years, but she is bringing up someone else’s. In Hong Kong, she’s employed as a domestic worker and a nanny to a 4-year-old boy she refers to as “my baby here.”

The 39-year-old has been supporting herself and her sister since they were orphaned as teenagers. Her sister is now looking after Macaraeg’s 16-year-old daughter, and Macaraeg sends part of her monthly salary home to support them.

Macaraeg says she was coerced by a recruitment firm called Angelex Allied Agency into taking out a loan of nearly $800 from CASH4U. The money was to pay for her training — and Angelex refused to return her passport to her until she paid, she says.

Angelex Allied Agency did not respond to the ICIJ’s requests for comment.

Macaraeg has fought back by volunteering for Migrasia and other groups that work to protect migrant workers, helping other workers targeted for unfair loans get refunds from their lenders. She recently founded her own Hong Kong-registered NGO to assist migrant workers who’ve been stuck with illegal recruitment fees.

Macaraeg is also advocating for herself, lodging a complaint against CASH4U with Philippine authorities. She says the lender stopped bothering her after she sent it a torrent of emails listing the laws she said the company had violated when it gave her the loan.

“I send lots of emails, so they are so scared,” she says.

Many overseas workers, she says, aren’t able to defend themselves in the same way because they aren’t yet aware of their rights.

“These companies keep intimidating the borrower,” she says, “so they can keep collecting money from them.”