PARTNER STORIES

Sex-trafficking survivors are increasingly suing to hold hotel chains liable for abuse on their properties, new investigation finds

As part of Trafficking Inc., The New Yorker and Berkeley Journalism’s Investigative Reporting Program uncover how franchised hotels have historically been a common site of human-trafficking crimes in the U.S. and examine a new legal push to make corporations pay.

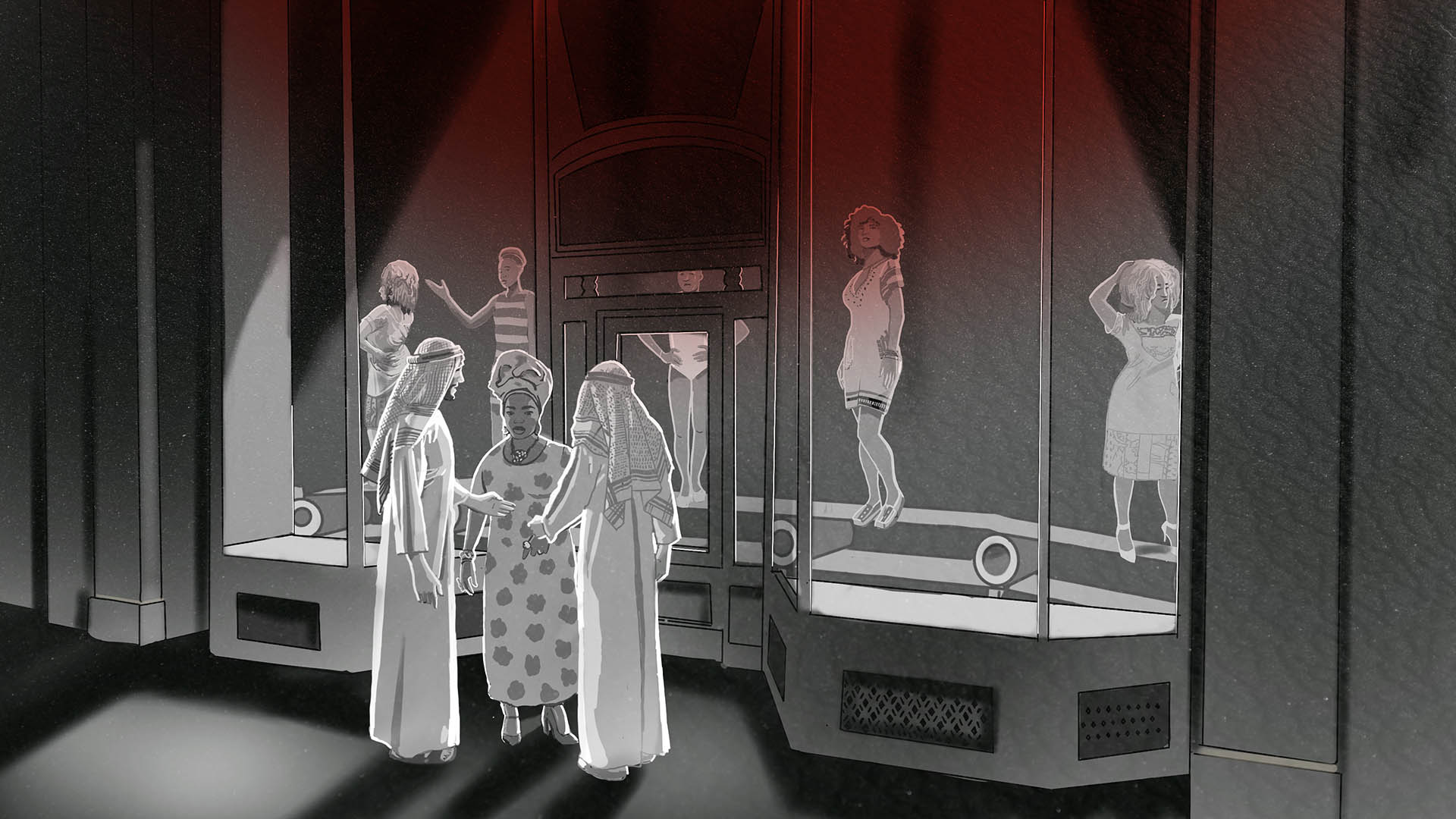

Some of the United States’ best-known hotel franchises have served as the backdrop to sex-trafficking crimes for decades, a new investigation by The New Yorker and Berkeley Journalism’s Investigative Reporting Program found. Now, a novel legal strategy is seeking to help survivors hold hotel corporations legally accountable for crimes committed on their premises.

In a 2018 Polaris Survivor Survey cited in the article, more than 60% of sex-trafficking victims said they were forced to sell sex from hotels.

“We focus not enough on how human trafficking intersects with the legitimate economy,” Louise Shelley, director of George Mason University’s Terrorism, Transnational Crime, and Corruption Center, said. “This is one of the key points in the supply chain where it does.”

The story, reported by Bernice Yeung, is part of Trafficking Inc., a global investigative collaboration led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists exposing the networks of companies and people that draw profit from various forms of human trafficking around the world.

One survivor, who went by the first name Anastasia, told The New Yorker and the Investigative Reporting Program how her trafficker, a drug dealer named Fredrick Brown, cycled her through hotels in four different states along the East Coast over roughly six months in 2013.

Mostly, though, she said she was kept at a Howard Johnson hotel in Pennsylvania, where the general manager, Faizal Bhimani, offered rooms to Brown in exchange for sex with Anastasia and others. At times, including when the police were in the area, Bhimani referred Brown to the nearby Pocono Plaza Inn, which shared an owner, according to The New Yorker article.

Yeung reported that years after Anastasia escaped the situation, she cooperated with a federal criminal sex-trafficking investigation. She and seven other women testified they had been forced to sell sex at the Howard Johnson. Both Bhimani and the company that owned the two hotels were convicted of aiding and abetting sex trafficking.

“This was open and notorious,” a federal prosecutor said at trial, according to Yeung. “This was obvious, and this was constant.”

Anastasia is currently preparing with a lawyer, Steven Babin, to file a separate lawsuit against Wyndham Hotels — the hotel corporation behind the Howard Johnson brand.

Wyndham cut ties with the franchised hotel where Anastasia was trafficked the same year as the trial. In a written statement, Wyndham said it condemns human trafficking and could not comment on litigation.

The case is among a wave of similar litigation over the past decade targeting hotel corporations that profit from franchised properties where sex-trafficking crimes occur.

“Thinking about it as who is in the position to most affect what’s happening and who’s benefiting the most from it — all signs point to these corporations,” Babin, who has filed a third of human-trafficking lawsuits against hotel corporations in the U.S., told Yeung.

The lawsuits fall under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, which was expanded in 2008 to allow survivors to sue anyone who benefits from an enterprise they knew — or could have known — was enabling trafficking.

The hotel industry has broadly taken a public stance against trafficking. But, as Yeung explains, the franchise model makes it difficult to take a proactive approach against trafficking.

Franchises have historically emphasized the independent ownership of their hotels to insulate corporations from liability issues related to safety issues or crime. Disclosure documents reviewed by Yeung from 10 major franchisers showed none had updated their contracts to explicitly cite trafficking as a basis for terminating a franchise agreement.

The first sex-trafficking case lodged against an individual hotel came in 2015. Since then, more than 110 sex-trafficking lawsuits have been filed against hotel franchisers, according to data the article cited from the Human Trafficking Legal Center.

Many of the key legal questions they raise have yet to be answered. None of the trafficking lawsuits against franchisers have gone to trial, though several have ended in settlements and about half are ongoing.

“Nobody’s seen litigation like this,” Annie McAdams, a Houston attorney who filed some of the earliest trafficking cases against hotel chains, told Yeung. “At the end of the day, it’s new. You’re creating what the law will be.”

Read the full story at The New Yorker.