Over the years the world’s most powerful fast-food chain, McDonald’s, has twice honored a Saudi prince’s business empire with its highest accolade for its franchisees: the Golden Arch Award.

Prince Mishaal bin Khalid al-Saud — who controls more than 200 McDonald’s outlets across Saudi Arabia — told CEO Magazine in 2018 that one of the secrets of his enterprise’s success is “ensuring a positive and favorable environment for our employees.”

Macrae Lee and Buddhiman Sunar recall a different environment. They say that they labored under harsh and unfair conditions at McDonald’s locations owned and operated by the prince’s Riyadh International Catering Corp.

Lee, who is from the Philippines, says RICC’s store managers ordered him to put in as many as 22 hours a day and hundreds of hours of unpaid overtime. He was denied days off for rest, he says, even when he was sick with fevers. When he tried to quit, a manager withheld paperwork that would have permitted him to find a new employer, he claims, leaving him jobless and begging on the street for food and water.

Sunar says he had to pay a stiff recruiting fee to an employment agent in Nepal to get a job at the prince’s fast-food outlets. Once he was in Riyadh, the Saudi capital, he worked 13- and 14-hour shifts with no breaks, he says. All the while, managers screamed abuse, he says, calling him “an animal” and asking, “Don’t you have a brain in your head?” If he stepped outside the restaurant, he says, he had to fill out an “incident report” explaining why.

“I felt trapped,” Sunar, who left his job with the Saudi McDonald’s franchisee in 2022, said in an interview with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. “I felt like I was in jail.”

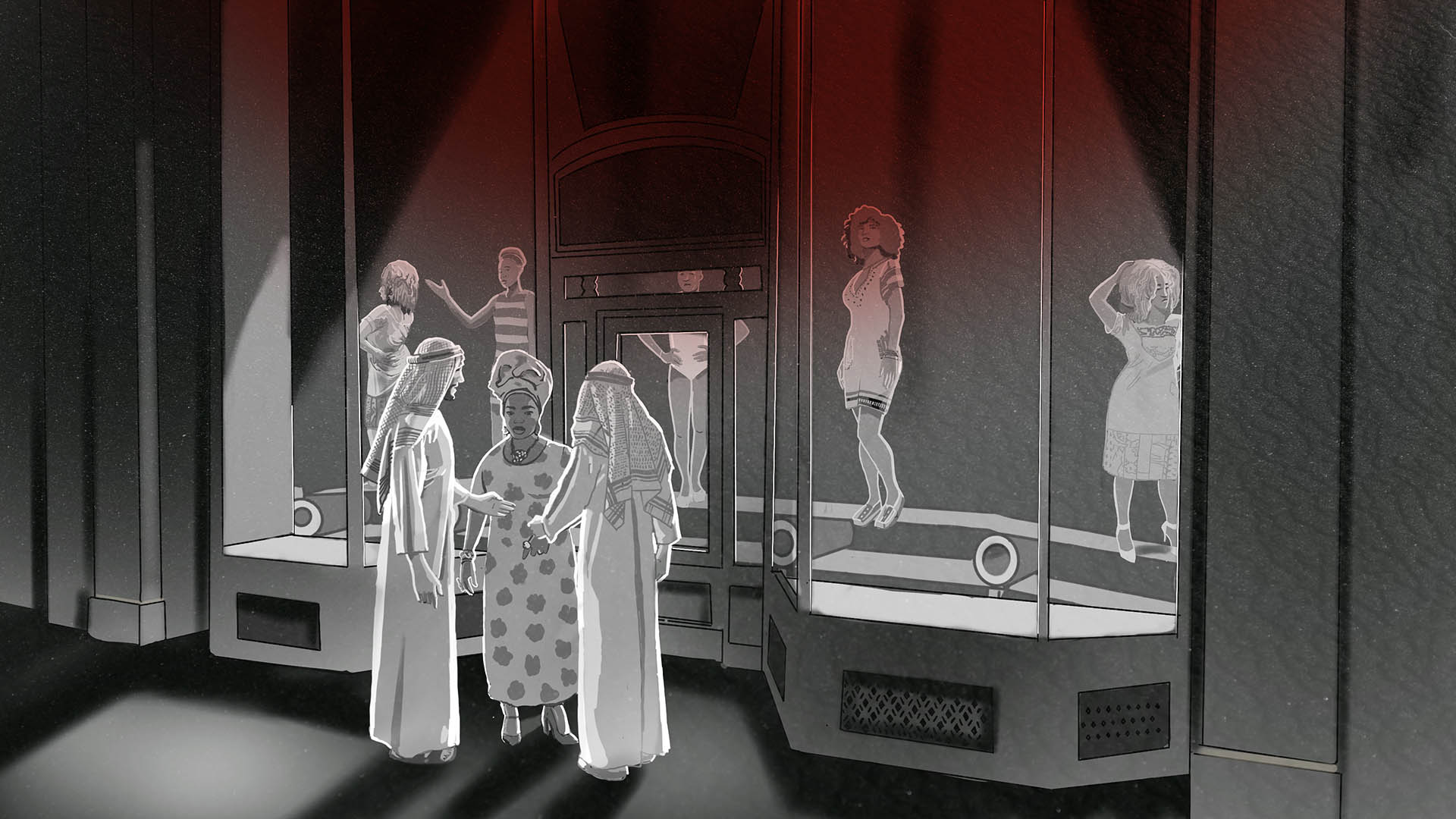

Lee and Sunar are among nearly 100 migrant laborers from Asia who told ICIJ that they’ve been subjected to repressive labor practices while working at Persian Gulf locations of four well-known American and British brands: McDonald’s, Amazon, Chuck E. Cheese and InterContinental Hotels Group.

The current and former workers say independent employment agents in their home countries coerced them into paying exorbitant recruiting fees, while labor contractors and workplace supervisors in Saudi Arabia and other destination countries subjected them to abuses that included confiscating their passports and limiting their freedom to leave their jobs.

These practices are widely identified as indicators of labor trafficking, which is defined by the United States and the United Nations as using force, coercion or fraud to exploit workers.

The workers were interviewed as part of Trafficking Inc., a joint investigation by ICIJ, the Guardian US, NBC News, Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism and other media partners. The latest installments in the investigation reveal how some of the world’s most recognized companies may be complicit in labor abuses through their overseas subsidiaries, franchises and business partnerships.

The workers who provided information for this investigation were employed through various arrangements. Workers for McDonald’s, Chuck E. Cheese and U.K.-headquartered InterContinental Hotels in the region are mostly direct employees of franchise holders or other local partners. Workers who say they came to Saudi Arabia from Nepal to work directly for Amazon instead discovered they were employed by Saudi labor supply firms that placed them in contract positions at the online retail giant.

Michael Page, deputy director of the Middle East and North Africa division at Human Rights Watch, says big companies have responsibilities under U.N. human rights standards to check their global operations and supply chains — even when the component is a franchise holder instead of a company-owned branch.

“Global corporate McDonald’s should absolutely be monitoring and verifying what is happening in its supply chain, whether it is in Saudi franchises or recruiters in the migrant origin countries where workers are hired,” he says.

In a statement, a representative from McDonald’s Corporation headquarters in Chicago calls the abuses detailed in the workers’ accounts “extremely troubling.” The statement says the global corporation updated its “ethical recruitment” standards last year to provide “a consistent approach” to protecting workers. These standards require that “no migrant worker pays for recruitment fees and related costs to secure their employment,” the statement says.

I felt trapped. I felt like I was in jail.

— Buddhiman Sunar, a former employee for a Saudi McDonald’s franchisee

RICC, the major McDonald’s franchisee in Saudi Arabia, did not answer questions for this story, but says in a statement that it’s in the process of updating its employment standards to align with McDonald’s enhanced recruitment standards. “Nothing is more important than ensuring the safety and respect of the employees who keep our restaurants running every day,” RICC says.

Amazon says in a statement that it was “deeply concerned” some of its contract workers were not treated with “the dignity and respect they deserve.” InterContinental Hotels Group and the Chuck E. Cheese brand’s parent, CEC Entertainment, say they take fair treatment of workers very seriously.

Harmful practices

Many of the 97 current and former workers interviewed for this story agreed to be identified by name. Others spoke on the condition that their identities not be revealed because of concerns about retaliation. To support their accounts, workers provided photos, videos and copies of hundreds of documents, including pay stubs, work certificates, passports, employment contracts and plane tickets.

In interviews with ICIJ, workers tied the four brands’ operations in the Persian Gulf region to one or more of these harmful labor practices:

• Charging big recruitment fees: Eighty-two of the workers report paying steep recruiting fees to independent employment firms in their home countries. This includes 18 of 21 workers at Prince Mishaal’s McDonald’s restaurants and all 54 Amazon contract workers from Nepal who talked to ICIJ.

Sunar, the McDonald’s worker from Nepal, says he paid more than $600 in fees to a firm in Nepal. The Nepali workers at Amazon warehouses report paying between roughly $830 and $2,300 in fees to local recruiting agents in their home districts or to large recruiting firms in Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital. Those are huge sums for a Nepali family living near the poverty line — and far above the limit of less than $85 that Nepal’s government says workers heading to the Persian Gulf can be charged.

Large recruiting fees are a major indicator of possible labor trafficking, the U.S. and U.N. say. Laborers often take out costly loans to cover the fees, trapping them into oppressive jobs to pay off their debt — a form of labor trafficking known as debt bondage.

Like McDonald’s, Amazon and InterContinental Hotels say their standards forbid workers in their labor pools being charged recruiting fees.

• Deceiving workers about the identity of their employer: Forty-eight of the 54 Amazon warehouse workers report that they were told by recruiting firms in Nepal that they’d be direct Amazon employees. Instead, their real employers turned out to be Saudi labor supply firms that placed them in temporary positions at Amazon. As a result, they say, they were tricked into working for a fraction of what they would have earned as direct employees of Amazon.

According to the U.N., deceptive recruiting practices — including making false promises about wages, working conditions and the identity of the employer — can indicate labor trafficking.

• Confiscating passports and other identity documents: All nine kitchen and service workers for Chuck E. Cheese franchises and five of nine housekeeping and food service workers for the InterContinental Hotels Group report local managers confiscated their passports.

An assistant restaurant manager for Chuck E. Cheese in the Persian Gulf region confirms that it’s “company policy” for the brand’s franchises in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to hold frontline workers’ passports — to make sure they don’t “run away from the company and work in other companies.”

Five workers for InterContinental Hotels Group say managers took their passports while they were working at Crowne Plaza and InterContinental hotels in Oman, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. A former housekeeping manager for an InterContinental hotel in the UAE confirms that management there confiscated line workers’ passports.

Global corporate McDonald’s should absolutely be monitoring and verifying what is happening in its supply chain.

— Michael Page, deputy director of the Middle East and North Africa division at Human Rights Watch

Passport confiscation is considered another key indicator of labor trafficking because it denies migrant workers’ freedom of movement, preventing them from leaving their jobs and their host country. This practice is illegal in the UAE and Saudi Arabia, but reports by the U.S. government and human rights groups show some employers in these countries continue to seize workers’ passports.

InterContinental Hotels Group says its policies require that workers “have freedom of movement at all times” and forbid confiscation of their passports. It said it’s investigating the information provided by ICIJ and its media partners “to ensure our policies are being fully implemented.”

CEC Entertainment did not address a question about the passport issue, but says that it regularly inspects Chuck E. Cheese restaurants in the region “to assess their operations, and during these visits, we have neither observed nor received reports of improper activities by our franchisees.”

• Limiting employees’ freedom to quit: Workers at Chuck E. Cheese and Amazon say Arab firms partnering with the big brands make it difficult for them to resign.

Seven of the 10 Chuck E. Cheese line staffers say local franchise managers delayed issuing documents — sometimes known as “release papers” — that are required under Saudi and Emirati law before a worker can seek a job with a different employer. Twenty Nepalis say Saudi labor supply companies that placed them in jobs at Amazon warehouses wouldn’t let workers leave the country unless they paid the labor firms exit fees that often equaled several months’ wages.

The abuses uncovered in this investigation may mean the American parent companies have breached the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, a federal law enacted in 2000 to protect trafficking victims and prosecute traffickers, legal experts say.

“In the United States, the Trafficking Victims Protection Act imposes liability on companies who benefit from participation in a venture that uses forced labor, provided that they knew or should have known of the forced labor,” says Agnieszka Fryszman, partner and chair of the human rights practice at Cohen Milstein, a U.S. law firm. “A franchise agreement would certainly seem to qualify as a venture, and any profit or market share would qualify as a benefit.”

Fryszman and other anti-trafficking experts say big corporations should aggressively monitor the labor practices of their subsidiaries and partners in the Persian Gulf region, which is known for weak labor protections and abuses against migrant workers.

Under the “kafala” system that operates in some Arab countries, foreign laborers’ legal and immigration status is tied to their employers. This gives employers broad control over them, leaving them open to exploitation. In Saudi Arabia and other countries where forms of the kafala system still exist, many foreign workers are fearful they can be punished if they leave an employer.

Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf countries have announced reforms of their labor laws in recent years. But human rights advocates say migrant workers in the region remain vulnerable because these limited protections have yet to be widely implemented or enforced.

“Migrant workers are still facing severe abuses despite these highly touted reforms,” says Page, the Human Rights Watch official. “Workers are still unable to change jobs easily without the permission of their old employer.”

Under the Golden Arches

Macrae Lee, the Filipino migrant worker, came to Saudi Arabia in 2018 to work at McDonald’s so he could send money home to his partner and his daughter, then a toddler.

An independent recruiting agency in the Philippines who placed him in the job promised him a salary of $450 a month, Lee says. But when he arrived in Saudi Arabia, RICC, the McDonald’s franchise holder, paid him just $325 a month, he says.

“I asked McDonald’s why my salary was less than what it says in my contract. McDonald’s told me to ask my recruitment agency. But my recruitment agency told me to ask McDonald’s,” Lee says.

A year later, he tried to move to a different employer. But the McDonald’s manager for RICC refused to give him release papers, Lee says. He was unable to work for four months, he says, and resorted to begging for help from other Filipino migrants he’d see on the streets of Riyadh.

They hired people from poor countries, so people are afraid to speak up.

— an anonymous worker at RICC, who says he’s working at McDonald’s against his will

Lee is one of 15 current and former employees who say managers at McDonald’s outlets operated by RICC make it difficult for employees to leave their jobs.

In addition to waiting months for release papers, workers say, local managers require them to pay fines if they leave before the end of their two-year contracts.

One current employee says RICC denied his resignation request, so he is now working in a McDonald’s uniform against his will. The worker, whose name and country of origin is being withheld to protect his identity, provided ICIJ with a screenshot of this resignation attempt. He says his managers told him he could not leave because of a “business need.”

“I’m fed up. I want to leave,” he says. “They hired people from poor countries, so people are afraid to speak up.”

In its statement, RICC says it works to be “a responsible and meaningful employer for the local communities we serve.” It says it provides “a variety of channels for employees to report concerns, including hotlines as well as regular visits to restaurants by our Human Resource teams.”

RICC’s president, Prince Mishaal, is a member of the Al Farhan branch of the House of Saud, which traces its lineage to a brother of the country’s founder.

When he took over the family’s McDonald’s franchise business in 1996, there were just 15 McDonald’s restaurants in RICC’s operating territory. As of this March, the firm reported it had 6,929 employees working at 220 branches spread across 36 cities and regions. Sixty-four percent of those workers were non-Saudis.

In his 2018 interview with Australia-based CEO Magazine, the prince said RICC benefits “from the strong support we get from the global corporation. We are privileged to have a high level of involvement from the McDonald’s global team in every aspect of our business.”

The prince also told the magazine he strives to “be there for my team and support them. My door is open 24/7 to every employee in this organization, from crew all the way up to senior management. In return, they will try to give their heart and soul to the business.”

Labor supply

In 2021, Surendra Kumar Lama landed at King Fahd International Airport in eastern Saudi Arabia after a long flight from Nepal. He thought he’d be met by representatives of Amazon. But that didn’t happen, he says.

Lama and dozens of other Nepalis say they discovered they weren’t going to be direct Amazon employees only after they landed in Saudi Arabia. Instead, they would be working for go-betweens — Saudi labor supply firms that would place them in positions at Amazon warehouses.

Because they had already paid big recruiting fees to employment agents back in Nepal, these workers say, they had no choice but to stay in Saudi Arabia and work under these unwanted arrangements.

One effect of working for the Saudi labor contractors, workers say, is they earned roughly $350 a month doing day shifts at Amazon warehouses, while colleagues who did similar tasks but were direct employees of Amazon earned roughly $800 to $1,300 a month. Another result, the Nepali workers say, was that they were often targeted for terminations and layoffs while direct Amazon employees from Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and other places were generally secure in their positions.

“The managers of Amazon told us that we were simply workers supplied by the [labor contracting] company,” Lama says. “If we did not work properly, they could terminate our work anytime. They said this during the first briefing when we started the work.”

Warehouse laborers who get fired or laid off say they often end up stuck for weeks or months with no wages and little food, waiting for the supply company to find them new work. Even if the firm doesn’t place them elsewhere, workers say, they can’t leave Saudi Arabia unless they pay the local firm a large exit fee.

Some of the workers at Amazon warehouses — and workers in the Persian Gulf region under the logos of McDonald’s, Chuck E. Cheese and InterContinental hotels — say limits over their freedom of movement extend even to their requests for time off to attend funerals, births and other family events back in their home countries.

When employees make these requests, workers say, local franchise or labor supply company managers often require them to enlist co-workers to sign contracts as “guarantors” who will pay a fine if the workers taking leave don’t return. Forty-three workers from the four brands confirmed this practice in interviews. Some say the local firms do this to ensure workers don’t use their leave time as a way of fleeing the country and escaping unbearable work situations.

In its statement, Amazon says it is working with the Saudi labor supply firm that employed most of the affected workers to “align on a compliance plan” that “includes ensuring their employees are repaid for any unpaid wages or worker-paid recruitment fees, are provided clean and safe accommodations, and that the vendor is committed to ensuring ongoing protections for workers.” It adds that it is “implementing stronger controls” and “providing enhanced trainings for our third-party vendors on labor rights standards with a specific focus on recruitment, wages, and deception.”

‘Sometimes I feel trapped’

The four years Rhandy Temperatura worked at a Chuck E. Cheese franchise in Saudi Arabia were difficult, he says, but he made the sacrifice so he could send money to support his family in the Philippines. At the restaurant, when he was around happy kids having birthday parties and playing arcade games, he cheered himself up by imagining they were his son.

When he decided to leave in 2019 because of low wages and unpaid overtime, he says, management delayed providing him the paperwork that would have allowed him to get a job elsewhere.

“After I finished my contract, I had to wait almost six weeks for the manager to give my release papers and passport,” he says. “I had no income during that time. … I survived by eating a diet of just bread.”

Chuck E. Cheese and its sister brand, Peter Piper Pizza, have footprints in 47 U.S. states and 17 other countries and territories, according to CEC Entertainment. Generations of American children and parents recall its tagline, “Where A Kid Can Be A Kid.” In Saudi Arabia, local franchises today embrace the motto “A place where the Fun begins and Friendship never Ends.”

Temperatura and other current and former employees describe a different side of the Chuck E. Cheese experience — one where local managers take away workers’ passports and limit their freedom to leave their jobs and find other work.

“I was shocked when they took my passport. That’s my own passport,” a South Asian employee of a Chuck E. Cheese franchise in Saudi Arabia says. “If I don’t have the passport I cannot apply to another company. This is against the Saudi government rules. Sometimes I feel trapped.”

A worker at a Chuck E. Cheese franchise in the UAE says her HR manager delays providing release papers to workers who want to resign “to punish the staff who want to go.”

CEC Entertainment says it demands “fair treatment of team members” from Chuck E. Cheese franchisees. “We will continue to hold our partners accountable to ensure they meet the high expectations and standards set by CEC,” it says.

‘We can’t move’

Workers for InterContinental Hotels Group’s franchises and partners in the Persian Gulf also report problems with resigning from their jobs.

“When we get better offers from other companies, we can’t move because the managers won’t allow us,” says a female worker in Oman at a Crowne Plaza, an American brand that’s part of InterContinental’s portfolio.

InterContinental says that respecting human rights “is an integral part of our global commitment to be a responsible business. We take all reports concerning labor and human rights issues within our hotels and supply chains seriously, investigate them comprehensively and are committed to ongoing human rights due diligence.”

Jho Atendido worked at an InterContinental hotel in Riyadh for 15 months before she returned to the Philippines in December. The mother of four says she was paid $400 per month working long shifts — including unpaid overtime — as a beach attendant, laundry assistant and cleaner.

Atendido says she was employed and paid through a Saudi labor supply company that placed her in a position at the hotel.

She says the conditions of the housing provided by the labor supply firm also made life difficult. She shared a dormitory room with 11 other women. They were given three small meals a day but were often hungry, she says, and they were not allowed to cook or bring snacks into the room. Guards would check their bags before they entered their compound, and those caught sneaking in food would be punished with salary deductions, according to Atendido.

They were not allowed to leave worker housing without permission from their labor firm’s management, she says.

“It’s like a jail. Management was afraid that maybe some of us would run away,” she says. “I was struggling so much working there because I’m a single mother. Life is like this. Some people are lucky, some are not. I’m not lucky in life.”

Contributors: Delphine Reuter (ICIJ); Shyam Karki (freelance); Tanka Dhakal, Eman Alqaisi, Mara Kessler and Hoda Osman (Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism).

—

Contributors to this story received support from the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the McGraw Fellowship for Business Journalism at CUNY’s Newmark Graduate School of Journalism.