ENVIRONMENT

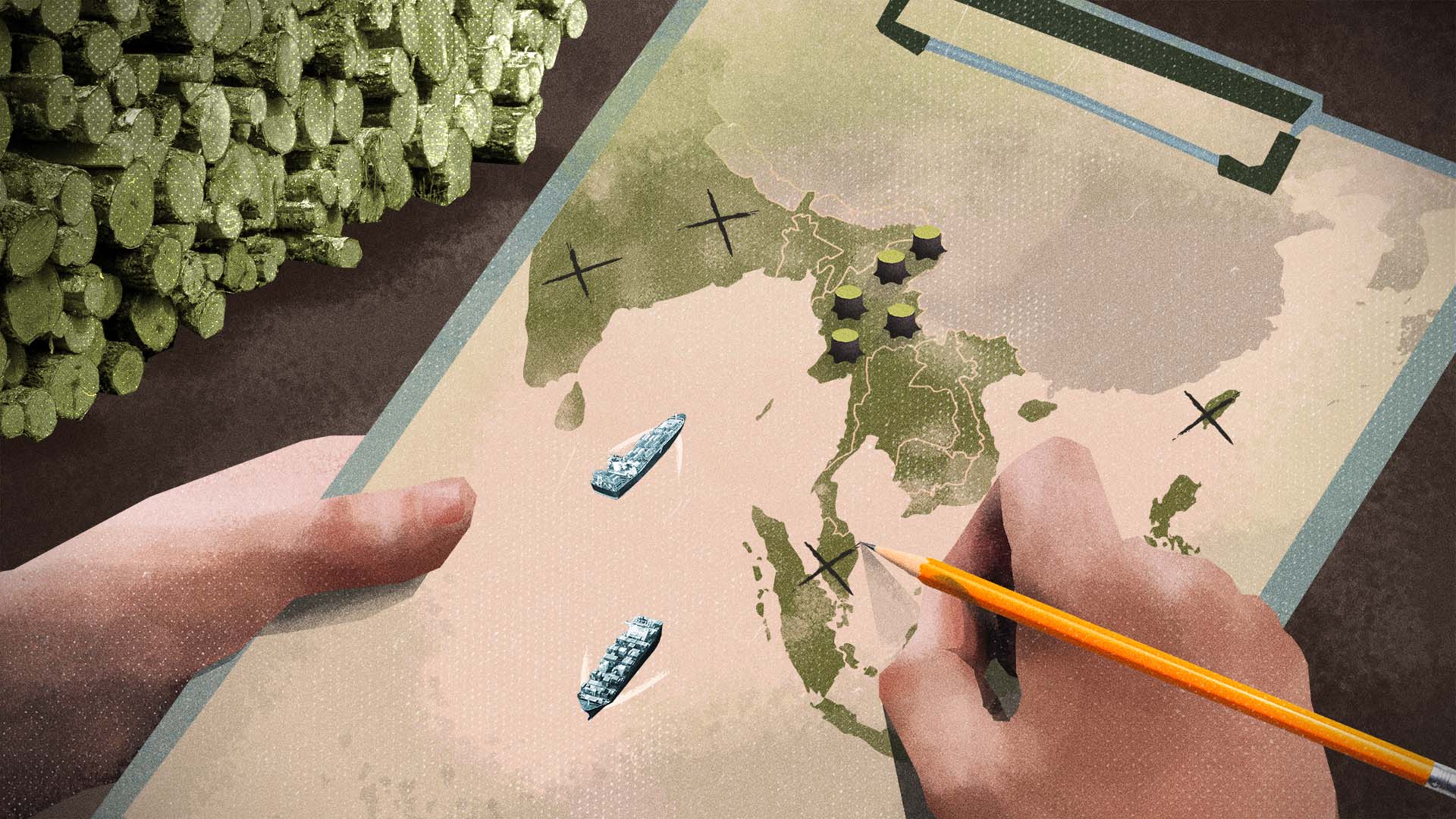

Myanmar’s controversial timber trade persists, despite Western sanctions

One year after the Deforestation Inc. exposé, ICIJ and its media partners found wood products have continued to flow from the military-controlled country into Europe and the U.S.

Last November, agents coordinated by the European Union’s law enforcement agency Europol seized a cargo of Myanmar timber that had been smuggled into the bloc illegally. While the finding was relatively small, worth about $13,000, it pointed to a more troubling phenomenon: the persistence of the illegal timber trade despite Western sanctions on the war-torn South Asian nation.

In Europe, Italy continues to stand out as a destination for teak and other controversial forest products. Between January and October 2023, Italian companies imported more Myanmar wood products than any other European country — about $3.3 million worth — for use in furniture and construction, according to Italian government data analyzed by the national timber trade association FederlegnoArredo and shared with L’Espresso, a media partner of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. The imports, which included teak, came two years after the EU imposed sanctions on the Myanmar state firm with a monopoly on timber production and long after a European panel of experts recommended a ban on all trade in Myanmar timber due to illegal logging concerns.

The new analysis is part of Deforestation Inc., a cross-border investigation led by ICIJ and launched in March 2023. The project, involving 44 media partners, documented how Western governments have failed to stop the trade of wood logged in conflict zones, such as Myanmar, allowing authoritarian regimes to finance their violent rule.

According to the junta-controlled commerce ministry’s own accounting, Myanmar exported $235.6 million worth of timber from October 2021 to mid-2023.

Myanmar teak is a particularly durable type of wood used for high-end architecture and yachts. It is also a vital revenue source for Myanmar’s brutal regime that toppled the country’s democratically elected government in 2021.

“Current imports of Myanmar teak into Italy should be down to zero,” said Alessandro Calcaterra, FederlegnoArredo’s director for Forests and Forest Certification and president of Italy’s wood-product importers and retailers trade association. Yet, he told L’Espresso, Italian companies “continue to import Myanmar teak via third parties in countries such as Indonesia and India.”

And they are not alone.

An ICIJ analysis of U.S. customs data from the ImportGenius database shows that U.S. companies and individuals were responsible for importing at least 300 tons of Myanmar teak shipped out of Yangon, the country’s commercial hub, in 2023. The U.S. importers included a small, artisanal shop in a Virginia suburb, a flooring manufacturer in California and a Maryland firm that supplies lumber to boat builders. These imports came after the U.S. government pledged to curb the trade of natural resources controlled by military forces, the analysis found.

Human rights groups and international organizations say those revenues finance the military regime that has killed, injured or forced into exile thousands of civilians.

Myanmar is also one of the countries with the highest rate of deforestation, according to the Forest Declaration Assessment, a coalition of conservation organizations.

‘More needs to be done’

After ICIJ and its media partners published their findings last year, the U.S. Justice Department announced the creation of an interagency task force to bolster efforts to combat the trade of wood products of illegal origins. EU officials told reporters that the European Commission was in “active dialogue” with member states facing “challenges of enforcement.”

The seizure of the Myanmar timber cargo last November was part of a larger crackdown by nine European and Latin American countries, which included raids by dozens of uniformed customs and environmental police agents in coordinated inspections looking for contraband wood products. The trade of illegal timber is the second most lucrative revenue source for organized crime after drug trafficking, according to Europol.

No yacht is worth the price of blood Myanmar people are sacrificing for this abhorrent trade.

— Yadanar Maung, spokesman for Justice for Myanmar

But, even as imports of Myanmar timber dropped by more than 80% in 2023 from a year earlier, EU officials publicly acknowledge a “problem” remains. Overall, European companies still imported at least $6 million worth of wood products from the South Asian nation last year, according to the data shared by the Italian trade association.

Yadanar Maung, a spokesman for the human rights advocacy group Justice for Myanmar, said these figures demonstrate that Western sanctions are not working as expected and that “far more needs to be done.”

“It’s unacceptable that Myanmar teak imports to the U.S. and EU are happening at all” three years after the coup, Maung told ICIJ.

“The sale of teak helps the junta pay for the bombs and jet fuel it needs to slaughter Myanmar people,” Maung said. “No yacht is worth the price of blood Myanmar people are sacrificing for this abhorrent trade.”

Is Europe prepared to fight deforestation?

In Europe, timber industry representatives are hopeful that a new EU law, which goes into effect at the end of the year and bans the imports of wood and other commodities linked to deforestation, could finally end the controversial trade.

The new law, called the EU Deforestation Regulation, or EUDR, requires most European companies importing palm oil, rubber, wood and other commodities to be able to prove the products did not originate from deforested land or contribute to forest degradation. The law also requires national authorities to conduct regular checks and act swiftly against companies that don’t comply; penalties include fines of up to 4% of a company’s annual turnover.

EU lawmakers say the EUDR should help reassure European consumers that their furniture, chocolate bars or cups of coffee have not contributed to the destruction of precious rainforests on the other side of the world.

Between 1990 and 2020, an area larger than the EU itself was lost to deforestation, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. In 2016, the FAO estimated that consumer products sold in the EU were responsible for about 10% of the loss.

But interviews by ICIJ’s European reporting partners have found that some governments appear unprepared to implement the new law.

Many national officials said they plan to rely on a new monitoring system shared among EU member states and other technologies to help authorities identify suspect imports. Several cautioned that they don’t have the manpower to carry out all checks required by the EUDR.

Eugen Gioancă, the deputy inspector general of Romania, which is home to Europe’s largest old-growth forests, told ICIJ media partner Context the country’s environmental police forces lack resources to address widespread illegal logging and timber trafficking. “There are currently not enough staff in the National Forestry Guard and Forest Guards to check operators and traders who place/export or intend to place/export timber or timber products on the market in accordance with the provisions” of the new law, Gioancă wrote in a statement.

Similarly, a spokesperson for Belgium’s federal environmental ministry told ICIJ partner De Tijd that it expects to have a 10-person team carry out all inspections — less than half of the 22 personnel the agency previously said was required.

The Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority of the Netherlands, one of the EU’s largest importers of wood products, palm oil and other goods at risk of being connected to deforestation, will have just seven full-time positions to implement the EUDR, a spokesperson told NRC daily, an ICIJ partner in the Netherlands.

The Dutch agency is currently “in discussion with the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality about expanding capacity” under the new law, the spokesperson said. The role of the Dutch team is particularly important since the country re-exports most of the products, according to CBS, a state-funded think tank.

Germany’s officers with the Federal Office for Agriculture and Food told ICIJ partners at NDR that the agency is expected to carry out about 2,500 inspections a year — a sharp increase compared to the roughly 200 conducted on average annually since 2010. According to the agency’s spokesperson, “on-site inspections are only planned in cases of concrete suspicion or on a random basis,” and will be decided depending on whether the goods are imported from a country considered at high risk of deforestation.

In Austria, where some of the world’s largest wood-processing companies are headquartered, five agents with the Federal Forest Office currently conduct about 30 inspections a year. After the new rules go into effect, the agency expects a “multiplication of official inspection activities,” its director, Peter Mayer, said in a statement to ICIJ’s reporting partner Profil.

Representatives from the European Commission, and Italy and France’s agriculture ministries in charge of implementing the EUDR did not respond to questions from ICIJ and its media partners.

For Johannes Zahnen, an environmental engineer who works for the conservation organization World Wildlife Fund, the new EU law represents a potential “step forward” in the fight against deforestation, but only if properly implemented.

The law can be “a lever to minimize forest destruction,” Zahnen told NDR. However, if governments don’t allocate enough staff, “that would be a first indicator that the EUDR is not being taken seriously,” he said. “That would be a disaster.”

Contributors: Jelena Cosic and Miguel Fiandor (ICIJ), Lars Bové (De Tijd), Karljin Kuijpers (NRC), Stefan Melichar (profil), Gloria Riva (L’Espresso), Benedikt Strunz (NDR), Mihaela Tănase (Context)