On July 15, 2000, the Marathon Oil Company sent $13,717,989.31 to an account in Jersey, an island in the English Channel with stringent bank secrecy laws. The owner of the Jersey account was Sonangol, Angola’s state oil company. The sum represented one-third of a bonus that the Houston, Texas-based company agreed to pay the Angolan government a year earlier for rights to pump the country’s offshore oil reserves.

That same day, Sonangol transferred an identical sum of money out of Jersey to another Sonangol account in an unknown location. Over the course of that summer, large sums of money traveled from the Jersey account to, among others, a private security company owned by a former Angolan minister, a charitable foundation run by the Angolan president, and a private Angolan bank that counts an alleged arms dealer among its shareholders.

Angola’s byzantine political and financial dealings are no secret; the country falls among the lowest rankings in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. Still, oil companies from the United States and other countries continue to do business with the Luanda government and Angola’s state-owned oil company. A variety of groups, from human rights organizations to diplomats, have raised concerns that oil revenue goes to government ministers’ pockets or to buy arms to fight the country’s recently ended civil war. But not even an International Monetary Fund monitoring program has been able to produce hard evidence of such activity.

The cost in human lives of this misdirection of the nation’s wealth is incalculable, and far beyond the estimated 500,000 killed in the 25-year-long civil war. For years, Angola has scraped the bottom of the United Nations’ social indicator indexes: 30 percent of its children die before the age of five, and average life expectancy is just 45 years.

According to the Angolan Petroleum Ministry, Angola exported $6.9 billion worth of oil in 2000, $2.9 billion of that exported by Sonangol. Economists estimate that up to $1 billion in oil revenue flowed out of the country and into private bank accounts in 2000 alone, despite a national law that gives ownership of Angola’s oil – and, presumably, the wealth it produces – to its citizens.

Now, an investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists provides a glimpse into this system where money from multinational oil companies moves through labyrinths of international bank accounts, avoiding national budgets and banks. It shows how national and international laws governing corporate behavior—including the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, enacted by the United States in 1977 after revelations of bribery by U.S. companies—have failed to prevent this movement of money from corporate accounts to private ones. And it reveals that oil companies around the world devote millions of dollars to influencing international policies toward the countries where they pump oil, often attempting to block the efforts of first world governments to sanction Third World countries where corruption flourishes and bloody conflicts rage.

Angola is certainly not unique as a country where conflict and corruption are fueled by petroleum dollars. In Sudan, where oil revenue from Chinese, Canadian and Malaysian petroleum companies reportedly doubled the government’s defense budget between 1998 and 2000, government forces have been accused of displacing tens of thousands of villagers to make way for oil concessions, often by bombing villages, burning homes and killing resisters. In 1993, Shell Oil became the focus of an international boycott when activist Ken Saro-Wiwa led thousands of Nigerians to protest the oil industry’s impact on Nigeria’s environment and culture. The late dictator Sani Abacha had Saro-Wiwa and seven other activists hanged for their temerity. Abacha is accused of stealing some $3 billion in state revenue during the five years he ruled Nigeria, money which that country’s current government is now trying to extricate from Swiss banks. And attempts by the newest petroleum hot spot in West Africa, Equatorial Guinea, to enter into an IMF loan program were put on hold by the institution out of concern for the government’s “lack of fiscal discipline and transparency.”

Some oil companies contribute to the problem directly by hiring corrupt government militaries to provide security for their operations. In Indonesia, Mobil Oil admitted to supplying food, fuel and equipment to soldiers hired to protect oil installations. The soldiers were later implicated in massacres in the breakaway province of Aceh and reportedly used Mobil’s equipment to dig mass graves, though Mobil denied knowledge of any abuses. In June 2001, the U.S.-based International Labor Rights Fund filed suit against ExxonMobil (the corporation formed of the merger between Exxon and Mobil) on behalf of Aceh villagers who suffered abuses at the hands of these soldiers. A similar situation occurred in Burma, where the ruling military junta is so brutal that nearly all foreign investment has pulled out of the country. In 1995, a Unocal official admitted not only to hiring Burmese troops to protect two natural gas pipelines but to supplying them with intelligence such as aerial photographs; a California court recently gave the go-ahead to a 1997 lawsuit filed against Unocal by Burmese citizens seeking compensation for the abuses they suffered by soldiers working for the company. Unocal has denied culpability. Unocal’s French partner, Total Oil, hired its own Burmese troops and supplied them with food and trucks, according to human rights groups and media reports.

Oil companies insist their job is to pump oil and not get involved in the politics of the countries where they do business. “The problem is that the good Lord didn’t see fit to always put oil and gas resources where there are democratic governments,” Vice President Dick Cheney remarked in 1996 when he was the CEO of the global oil services giant, Halliburton Company. But in countries with unstable governments, rebel insurgencies, and widespread corruption, such official distance can be hard to maintain.

‘Turning a Blind Eye’

The motor of Angola’s economy floats 100 miles off Africa’s Atlantic coast on a ship the size of a football field. Rigs rise hundreds of feet in the air from a steel platform moored to the ocean floor 440 feet [1,360 meters] below by steel chains and flexible pipes that suck oil from the sea bed into the ship’s gigantic hull. Costing $2.6 billion, the ship that pumps oil from the Girassol field (Girassol is the Portuguese word for sunflower) is the biggest and most expensive of its kind, capable of storing 2 million barrels of oil, housing 140 people and generating enough electricity to light a city of 100,000.

Since the 1973 and 1979 oil shocks, Western corporations and governments alike have sought supplies of crude oil beyond the Persian Gulf. Already, one in every seven barrels of oil that the United States imports comes from Africa, and that figure will likely increase as the United States continues to diversify its oil sources, especially following the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. By 2015, a report by the National Intelligence Council predicted, a quarter of all the oil America imports will come from West Africa.

Angola will be one of the prime beneficiaries of that diversification. The country lies on the southern curve of the Gulf of Guinea, anchoring an oil-rich geologic shelf running across the Atlantic from Brazil that has turned Nigeria, Cameroon and Gabon into major crude exporters.

Angola’s oil resources were first developed in 1956 when the country was a colony of Portugal, which ruled Angola until 1975. Immediately after the Portuguese pulled out of Angola, an armed struggle for control of the country flared among the Marxist-based Movement for the Popular Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the Front for the National Liberation of Angola (FNLA), and the National Union for Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). The MPLA managed to establish a functional government in Luanda and in 1976 created a national oil company, Sociedade Nacional de Combustiveis, known as Sonangol, to manage the burgeoning oil industry. From the start, Sonangol’s revenue was appropriated as a war chest to fund the long fight against UNITA, which was funded by sales from diamonds and timber as well as South Africa’s apartheid regime and the U.S. government. The FNLA, the MPLA’s other rival, had disintegrated as a movement by the late 1970s.

The war barely touched Angola’s oil production, largely because the bulk of the reserves are offshore. Angola produced an average of 742,000 barrels of oil per day (bpd) in 2001. The massive Girassol field, which began producing oil in December 2001, boosted that figure to 860,000 in January 2002, and is projected to increase Angola’s output to nearly 1 million bpd by the end of 2002. As more fields begin producing, oil industry analysts expect Angola to reach 2 million bpd by 2007, generating up to $14 billion annually for the Angolan government.

Oil provides the bulk of the Angolan government’s revenue; in 2002, oil money will account for more than 90 percent of Angola’s $5 billion budget. The government has traditionally devoted a large portion of its budget to military spending, ranging from 27 percent to 41 percent between 1995 and 1999. The combined spending on health and education accounted for less than 11 percent during the same period. Yet the same 1978 law that established Sonangol names Angola’s people as the sole owners of its petroleum.

Those with experience in Angola, from business executives to workers with non-governmental organizations to members of Angola’s opposition parties, acknowledge the system’s existence. However, the diplomatic and business worlds have been loathe to raise their voices in protest because of their stake in Angola’s oil wealth. Even financial institutions such as the IMF and World Bank avoid direct implication of the Angolan government in their reports, pointing out in private that their agencies are tasked with restructuring economies, not investigating them. Yet all acknowledge the system’s draining effect on the country’s economy.By the late 1980s, the Angolan government’s fight against UNITA had become so costly that it began racking up debt from foreign lenders it couldn’t pay back. The resulting poor credit ratings, combined with exploding inflation, gutted the country’s economy and central bank. To maintain foreign investment, the government opened up a series of bank accounts outside Angola as a safe arena in which to conduct business, said Sonangol CEO Manuel Vicente. A complex system of offshore accounts and trusts emerged that allowed oil money to move directly to foreign creditors without passing through the government’s budget or banks, according to Global Witness, a London-based advocacy group that examines conflicts linked to natural resources.The cause of this gap between resource wealth and terrestrial poverty, familiar in many oil-producing states, is the topic of much study and debate. Angola has fallen prey to a common ailment of oil-rich countries in which they become over-reliant on mineral wealth and fail to develop other sectors of their economy. However, its government has also earned a reputation as one of the world’s most corrupt, with its lopsided military spending, budgetary mismanagement and resistance to external supervision. The IMF discontinued a program designed to prepare the country for debt-relief structuring in August 2001 after Angola failed to meet benchmarks like lowering inflation and increasing fiscal transparency. In July 2001, Médecins Sans Frontières released a damning report accusing the government and UNITA of “turning a blind eye to the obvious, serious and often acute humanitarian needs of the Angolan people.”

In 2000, the IMF asked Sonangol to conduct an analysis, or “diagnostic,” of its accounting practices, one of a list of benchmarks the government had to meet in order to qualify for the debt-restructuring program. The accounting firm KPMG, which won the contract for the diagnostic, was tasked with comparing payment records and production figures for 1999 and 2000 to government budgetary figures. The diagnostic did not, however, examine how past revenue was spent; in fact, the government of Angolan President Jose Eduardo dos Santos insisted that the diagnostic extend no further back than fiscal year 1999. It is up to the Angolan government whether the diagnostic’s July 2002 final report will be released to the public. Two interim reports have been kept confidential.

“We’re trying to work out where all this money is going,” an accountant familiar with the diagnostic told ICIJ. “Most or all of the money goes to offshore bank accounts and disappears somewhere. (Sonangol) is bypassing the central bank, dollars are going outside the purview of the bank, and the bank is not aware of what’s going on.”

Follow the Money

Vicente, Sonangol’s chief executive, appears to be a jovial man as he smiles over a drink in the bar of Washington, D.C.’s, swank Four Seasons Hotel. Vicente speaks proudly of Sonangol’s many subsidiaries – including a shipping company, a telecommunications branch and an aviation company – its investments in the oil industries of neighbors such as Cape Verde and Congo, and the inauguration of a “Houston Express” plane shuttle from Houston to Luanda funded by a coalition of U.S. and Angolan businesses.

“Basic risk management” is what Vicente calls the structure. “You don’t want to have all your eggs in one basket.”Vicente admits that Sonangol maintains “around 10” bank accounts in several locations outside Angola, including in Switzerland, Portugal and London. The accounts are affiliated with either Sonangol’s London or New York satellites, established chiefly to facilitate the oil trading done through those offices, he said.

One of those accounts, Vicente says, was established in 1983 with Lloyd’s TSB on the isle of Jersey in the Channel Islands. Jersey is one of the world’s busiest offshore banking havens, known for closely guarding the identities of its depositors and generating criticism from other European nations for not cooperating with investigations into money laundering. Jack Blum, a Washington, D.C., attorney specializing in international fraud and capital flight, points out that since England does not tax bank accounts held by foreign parties, there can be only one incentive for maintaining an account in Jersey rather than London.

“The incentive for keeping money in a place like Jersey can only be secrecy, but a parastatal company should be anything but secret,” said Blum. “When companies ask me about red flags signifying when a payment is suspicious, I say, ‘when they want a large amount of money sent to an offshore account.'”

Sonangol financial information obtained by ICIJ, charting activity from June 1 to Sept. 1, 2000, shows an interconnected web of 14 different Lloyd’s accounts. Some are dormant and collect only small interest payments, some move several million dollars a day. Though they cover only a three-month period, the accounts’ stream of money provides a glimpse of the structure of subterfuge behind which national revenue can hide.

Sonangol, itself, accounted for more than half the traffic: the Jersey accounts saw some $78 million pass through on the way to other Sonangol branches and accounts. The account also received a $330,000 deposit from the national oil company of the West African island-nation of Sao Tome and Principe, of which Sonangol owns a 40-percent stake, and a $60,000 deposit from the Congolese national oil company, in which Sonangol also invests.

Yet aside from these transactions, less than 1 percent of the total paid out went to companies directly involved with the oil industry, such as oil service providers or consultants. The rest went to address government economic priorities, such as servicing debt from oil-backed loans. The fact that government business was conducted through offshore Sonangol accounts – and that Sonangol receipts never made it back to Angola – violates a 1995 Angolan law requiring all foreign currency receipts and government revenue to pass through the central bank.

When Angola’s financial instability led creditors to demand more concrete forms of collateral, it turned to its most valuable resource – oil. Oil-backed loans are repaid with proceeds from oil sales that go directly to creditors, bypassing budget ledgers. Transparency advocates criticize oil-backed loans because they allow money to vanish into what one economist called a “black hole.” Financial institutions like the IMF also frown on them because the high-interest rates of the short-term loans cost Angola an estimated $50 million a year. Global Witness counted seven loans worth $3.55 billion between September 2000 and October 2001 alone, despite Angola’s agreement with the IMF to limit borrowing in 2001 to $269 million.

The Jersey accounts show what a quick and potent injection of cash such loans can bring: Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS) alone pumped $35.6 million into Sonangol in the three-month period, while Sonangol paid UBS only $171,000 in debt servicing. UBS has extended some $1 billion in oil-backed loans to Angola since 1989, including a March 1999 loan providing $575 million.

Aside from money that Sonangol transferred to its subsidiaries during the three-month period, the largest block of cash to leave the Jersey accounts – some $7.2 million – went to construction companies. Some of the global construction industry’s largest names, such as Odebrecht of Brazil, Engil of Portugal and Dar Al-Handasah of Egypt, are deeply involved with the Angolan government’s plan to rebuild the country’s infrastructure. Odebrecht has contracted with the government for a number of major infrastructure jobs, such as constructing the country’s public water and irrigation network. Dar Al-Handasah, which maintains an office in Luanda, built the government’s new administration complex and the city’s water supply system.

Executives from several of these construction companies, as well as oil companies, hold seats on the boards of Fundacao Eduardo dos Santos (FESA), the president’s personal charity foundation, which also received $33,333 from the Jersey accounts. Charitable organizations are another “black hole” in Angola’s financial galaxy into which millions of dollars have allegedly disappeared. The Angolan government requires most foreign investors to contribute money to social development projects, such as rebuilding schools or roads, according to oil industry sources. Sonangol created a “social bonus fund” to receive this money, though the number of bank accounts linked to the fund have reportedly mushroomed to more than 20, and the boundaries between them and Sonangol’s myriad other accounts are unclear. For example, $100,000 left the Jersey accounts in August 2000 for the Vatican, which directed it toward a branch of the Capuchin Order, based in Luanda, to build a social activity center.

The foundations tasked with carrying out the projects have also been tainted by allegations of corruption, particularly FESA. The foundation describes itself as a government partner in initiatives ranging from professional training to building universities and orphanages. Critics, however, call it a personal slush fund for Dos Santos that fortifies his myth by crediting him for projects such as building schools that should be funded by the state anyway. Executives from Odebrecht, Dar Al-Handasah, U.S. oil company Texaco, Norwegian oil company Norsk Hydro, Israeli security company Long Range Avionics Technologies and several Sonangol executives sit on FESA’s general assembly and project boards. (ICIJ sought to interview Dos Santos about FESA and other matters, but a request to the Angolan Embassy in Washington, D.C., went unanswered.)

Neither the government nor Sonangol will divulge how much money these “social bonus fund” accounts contain, though the figure has been estimated at $60 million to $200 million. Some $150 million in payments to secure contracts, known as “signature bonuses,” reportedly found its way into another fund named the Fundo de Desenvolvimento Economico e Social in 1999, though the government will not reveal how or where the money was spent.

Close presidential relationships are in evidence in other account transactions as well: On June 5, two payments totaling $2.4 million went to Teleservices, a private security firm that guards diamond mines and oil-storage facilities in Soyo and Cabinda. Teleservices’ principal shareholders are Gen. Antonio dos Santos Franca, a former military chief of staff and Angolan ambassador to Washington, and former Angolan Chief of Staff Joao Baptista de Matos. On Aug. 15, 2000, $2.2 million was paid out to Banco Africano de Investimentos (BAI), Angola’s first private bank, in which Sonangol is also a 17.5 percent shareholder. Other shareholders include a company owned by Pierre Falcone, an alleged arms dealer arrested in 2000 in connection with the French oil-for-arms scandal known as Angolagate, whose trial is ongoing. (Attempts to reach Falcone for comment through his lawyers were unsuccessful).

Two of the largest payments – $1.6 million and $3.9 million, each on Aug. 2, 2000 – went to Concord Establishment. Concord Establishment is the Liechtenstein-based parent company of Catermar, which provides catering and other support services to the oil industry. Catermar, based in Lisbon, has worked with Sonangol for more than 20 years, and recently entered into an agreement with Sonangol to operate a chain of supermarkets in Luanda. Catermar CEO Luis Correa de Sa says the large payment went toward several outstanding bills Sonangol had accumulated.

The significance of the Sonangol transactions lies not in any single one, but in their indication that large amounts of oil wealth are moving through accounts and settling government business out of the purview of budgetary monitors. Under Angolan law, all government revenue, including Sonangol receipts, should be channeled through the central bank. CEO Vicente says Sonangol reports on income from each barrel of oil to Angola’s Parliament at quarterly meetings and directs all of the profits remaining after the company pays its bills to the central bank as required by law (though the company does collect a fee for oil trading). However, when asked why an outside contractor such as Teleservices, which provides services in Angola, was paid from an outside bank rather than the central bank as required by law, Vicente qualified the payment as a “mistake.”

“We had a lot of weaknesses and problems here two years ago, but we have made an agreement with the government to restructure the company,” Vicente claimed, maintaining that the discontinued IMF program was part of that effort.

The Signature Bonus

Amid the stream of executives rolling their overnight cases in and out of Washington’s Four Seasons Hotel in December 2001 were lawyers for some of America’s largest corporations – Conoco, General Electric, Enron and Boeing, among others. They were in Washington to attend “What Every In-House Counsel Should Know About the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act,” an annual conference organized by the American Conference Institute to boost U.S. companies’ awareness and enforcement of the act. Attendees listened as representatives from the U.S. Justice Department and Transparency International spoke on topics such as “Dealing With Corruption by Foreign Competitors in International Markets” and “Accounting and Record Keeping: What’s Required and the Implications of Getting it Wrong.”

The oil industry became almost synonymous with bribery in 1973 when Gulf Oil admitted funneling more than $10 million to U.S. and foreign politicians over several years. When the Securities and Exchange Commission responded with a questionnaire asking American corporations if they paid bribes, more than 400 corporations – including major oil companies like Exxon – acknowledged making questionable payments to foreign government officials, politicians and political parties. The result was the passage in 1977 of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act – the world’s first, and toughest, anti-bribery legislation.

The FCPA does contain some significant loopholes, such as the exemption for “facilitating payments,” defined as “payments to facilitate or expedite performance of routine governmental actions.” These actions include processing of permits, licenses or visas, but “do not include any decision by a foreign official to award new business.” Yet, according to Phillip Urofsky, an attorney at the U.S. Justice Department – the agency charged with criminal enforcement of the act – the exemption also covers one of the most nebulous transactions in the oil business, the signature bonus.

U.S. businesses complained that the law put them at a competitive disadvantage against companies from countries such as France, which once considered bribes a tax-deductible business expense. Andre Tarallo, a former executive with the French state-owned oil giant, Elf Aquitaine, which merged with TotalFina to form TotalFinaElf in 2000, testified in July 2001 before French prosecutors that Elf Aquitaine had skimmed pennies off every barrel of African oil since the 1970s to maintain secret slush funds in Liechtenstein and Switzerland for payouts to African leaders. The beneficiaries included heads of state from Gabon, Congo-Brazzaville, Cameroon, Nigeria and Angola.

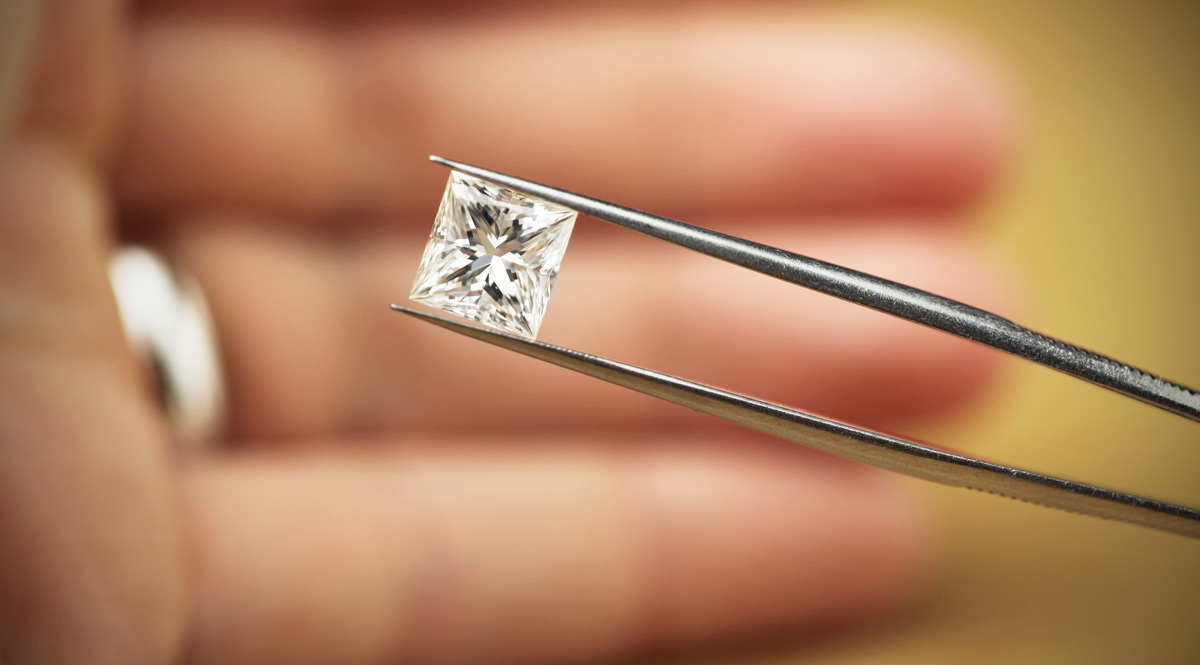

Signature bonuses are lump sums companies pay foreign governments upon signing a contract licensing them to explore and pump oil from a specified area, or “block.” The amount of the bonus varies according to the block’s size and prospective wealth. In recent years, the size of signature bonuses has skyrocketed in hot markets such as Angola. The $870 million bonus paid by BP-Amoco, TotalFinaElf and Exxon for the ultra-deepwater blocks 31, 32 and 33 in 1999 set an industry record, and the $300 million signature bonus paid by four partner companies for block 34 kept the bar high. Among the largest transfers into Sonangol’s Jersey island accounts during the third quarter of 2000 was the $13.7 million from Marathon Oil – just one-third of the signature bonus the company had agreed to pay for the opportunity to share in Angola’s oil wealth.

The amount of the bonuses are set in a two-tiered bidding process: all of the companies selected by the host government to share ownership of the block submit a “base bid,” the amount of which is widely known within the industry. Companies then submit a second bid to determine the size of their share, an amount that is tightly guarded. “It’s far from bribery – it’s a very normal practice around the world,” said Knud Schlosser, vice president of Norsk Hydro, which holds shares in four Angolan blocks. “It’s a very clean business.”

In his testimony before the French magistrates, however, Elf’s Tarallo used another term for the practice. “All international oil companies have used kickbacks since the first oil shock of the 1970s to guarantee the companies’ access to oil,” Tarallo said, according to news reports at the time. “You have official ‘bonuses’ as part of a contract: the company seeking to exploit an oil field commits itself to building a school, a hospital or a road. Then you have ‘parallel bonuses,’ which can be paid to increase the likelihood of obtaining the contract.”

Another difficulty in determining the “cleanliness” of the bonus system is that payments rarely appear in corporate annual reports or financial filings. While a few countries, such as Norway, require companies to detail their accounts in a state registry, most do not. In the United States, the most detailed financial information a publicly traded oil company must release to the public appears in its shareholder reports. Companies may break down expenditures in annual reports by region, but provide little detail beyond that. For example, the 1998 annual report for Chevron said only that the U.S. oil company spent $87 million on property acquisition, $329 million on exploration and $584 million on development in Africa in 1998. The industry publication Offshore said Chevron had spent $400 million in 1998 on developing a deep-water oil field off the coast of Angola, but whether that figure was included in the company’s development total was unclear.

Transparency advocates such as Global Witness say oil companies must assume responsibility for their contribution to corruption by releasing details of their payments to foreign governments to the public. Such challenges, combined with public relations debacles such as that of Shell in Nigeria, have resulted in projects like the United Nations’ Global Compact, in which several oil and mining companies, including British Petroleum (BP) and Shell, agreed to a set of principles intended to safeguard human rights while protecting employees and property in remote parts of the world. Chevron, Shell, Texaco, U.S. company Occidental Petroleum and Norway’s Statoil have all signed the Sullivan Principles, based on a 1977 code of conduct authored by American minister and activist Leon Sullivan for companies operating in South Africa, which declare signatories’ intent to “not offer, pay or accept bribes.”As long as oil companies keep the size of the signature bonuses they pay a secret, the potential for diversion from Angola’s budget is huge. Only half of the $870 million signature bonus for blocks 31-33 appeared on government ledgers, and Angola’s former Foreign Minister Venancio de Moura acknowledged in December 1998 that the funds were earmarked for the “war effort.” Some economic reports have estimated the amount of oil revenue missing from Angola’s 2000 budget at $1 billion – a sobering figure considering that the bulk of Angola’s budget is funded by oil and that the country is expected to receive some $23 billion worth of investment in its oil and natural gas sectors by 2007.

Yet adopting a code of ethics doesn’t guarantee it will be followed. “Let us be realistic,” Ho Wang Kim, the Angola officer at Energy Africa, told ICIJ when asked whether his company followed a code of ethics. “No oil company seeking ventures in Africa practices a noble and transparent code of ethics and principles [in order] to have a competitive edge over its competitors.”

‘Just the Standard’

In October 2000, British Foreign Office Minister Peter Hain convened a private meeting attended by representatives of several of the largest oil companies active in Angola, including BP, Exxon and Chevron, together with advocacy groups including Global Witness and Transparency International. The purpose of the meeting was to persuade oil companies to publish financial data on their Angolan operations, which would allow Angolan citizens to know how much money was being sucked away by government corruption. Two months later, in February 2001, BP sent financial records, disclosing a $111.7 million signature bonus the company paid to Sonangol in 1999 for block 31 to Companies House, a British national archive, in the name of furthering transparency. Since BP’s 26 percent share was public knowledge, and contract language stated that oil companies must carry Sonangol’s stake, observers were quickly able to calculate the total signature bonus paid by all the partners in block 31 at $355 million. The company also announced it would annually publish data on oil production as well as any payments or taxes paid under its contracts with the Angolan government.

The announcement was met with applause from human rights organizations, but a disparaging silence from the oil industry, which refused to believe that BP could take such a step without violating the terms of its contract. The sole response was from BP’s block 17 partner TotalFinaElf, which issued a press release promising it had turned over “precise technical and financial information” to the IMF and World Bank, but would not release it publicly.

BP answered its critics by noting that after poring over the contract, its attorneys had concluded that the terms did not override a British law requiring companies to report significant payments. “The financial information we have already published did not breach the contract since it was an obligation of U.K. law,” said BP spokesman Toby Odone.

Of the 13 oil companies with major stakes in Angola interviewed by ICIJ, all (with the exception of ExxonMobil, Agip and Ranger, which refused comment) claimed that contract confidentiality clauses prevented them from releasing any financial information, and were unwilling to share any details, including the confidentiality clause language, of their contracts. This hesitancy may be partially explained by a Feb. 21, 2001, letter to BP in which Vicente expressed Sonangol’s position on the company’s decision. Headlined “Unauthorized Disclosure of Confidential Information” and copied to several other oil companies, the letter stated, “With great surprise and disbelief, we have read in the press that your company has been disclosing information about your petroleum activity in Angola, including strictly confidential information. … If this can be confirmed, then it is good reason for applying the provisions of Article 40 of the PSA, i.e. termination. Finally … we strongly recommend our partners not to adopt similar attitudes in the future.”

Aside from the government’s strong-arm tactics and contract confidences, many company executives said they would never release financial information for “proprietary” reasons. “Oil companies generally don’t publish what they pay for permits,” said TotalFinaElf spokesman Thomas Saunders. “Whether it’s the oil industry or any other industry, obviously you wouldn’t want your competitors to know what you pay. It’s not that we’re against it, or that there’s something to hide; it’s just the standard.”

Companies also equated opening their books with dictating to – and potentially alienating – other governments, something they are loathe to do. “I think it’s unwise and unrealistic to assume that businesses can fulfill the role that the international community has had difficulty accomplishing,” said Geir Westgaard, a vice president of Statoil. “Our industry has to be sensitive to accusations of being too political, of meddling with governments … there can be a whiff of neo-colonialism.” Agreed Texaco spokesman Andrew Norman: “We recognize that we have a responsibility to the people of Angola, but when it comes to government policy we feel very strongly that it’s not our role … to suggest or [try to] influence national economic policy.”

Yet scores of lobby documents, financial records and testimony reviewed by ICIJ attest to the fact that influencing national economic policy – both in their own countries and in the lands where they operate – is as integral to an oil company’s function as drilling holes. In fact, of the 50 oil companies ranked the world’s largest on the basis of their oil and gas reserves, production and sales, 23 of them maintain representatives in Washington. More than half of those companies are based in other countries, attesting to the impact they believe U.S. policy can have in foreign lands. In addition to lobbying, the oil and gas industry contributed $33.7 million to federal candidates and political parties in the 2000 U.S. election cycle, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, which tracks political campaign contributions.

Documents filed under the U.S. Lobbying Disclosure Act between 1996 and 2001 demonstrate the importance oil companies give to foreign issues. Before its merger in 1999 with BP, the list of foreign issues that U.S. company Amoco regularly lobbied on surpassed energy or even environmental issues, normally the first priority of petroleum companies. For example, in 1998 Amoco lobbied on U.S. relations with Africa, Nigeria, Angola, Azerbaijan, China, Colombia, Romania, Venezuela, Algeria, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Mexico, Trinidad and Tobago, Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran and Georgia. It also lobbied on legislation including the Silk Road Strategy Act, European Energy Charter and the Free Trade Act of the Americas, as well as annual foreign appropriations bills.

Sanctions have been a longtime focus of aggressive lobbying by the petroleum industry, an ardent foe of any legislation that blocks investment and operation in other countries. Chevron, Texaco, Conoco, Phillips and Mobil all lobbied in support of the Enhancement of Trade Through Sanctions Act of 1998 and the Sanctions Policy Reform Act of 1999, which would have limited and modified international sanctions. (ExxonMobil simply listed the issue as “unilateral sanctions”). Most companies lobbied against the Iran and Libya Sanctions Act, however; even the Italian company Eni and Australian company BHP lobbied the U.S. Congress over sanctions against Iraq, Iran and Libya.

Africa garners a large amount of attention from lobbyists. Texaco has lobbied on “foreign trade and investment in Angola and Nigeria;” ExxonMobil on the “Chad/Cameroon development project;” Shell on “issues related to Nigeria and southern Africa;” Conoco on “U.S. policy toward Nigeria;” Phillips on

“Angola/Nigeria transparency issues;” BP on “improved U.S.-Angola relations,” and several companies on the Nigeria Democracy Act of 1998.

Perhaps the most significant African trade bill passed by the U.S. Congress in the last several years is the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOB). The petroleum industry put all its muscle behind the bill, which aimed to enhance trade between the U.S. and sub-Saharan Africa by negotiating free-trade areas and reducing tariffs. AGOA met with significant opposition upon its introduction in 1996 for, among other things, conditioning trade benefits on economic reforms like privatization, while neglecting issues like debt relief and the environment. However, a special-interest group called the “Africa Growth and Opportunity Act Coalition Inc.” was formed to lobby for the bill in Congress by some 45 corporations, including Chevron and Texaco, and lobby shops such as Cohen and Woods and C/R International (both of whom represent countries that would benefit from the bill). Articles in oil industry trade papers said the bill would create windfalls for oil companies already in Africa by shrinking the price of oil on the U.S. market and saving companies taxes. The bill was signed into law by then-President Bill Clinton in May 2000 and expanded by Congress in 2001. Oil executives argue that directly influencing a sovereign government and lobbying on U.S. foreign policy are two separate things: however, policies such as sanctions and trade agreements can shape nations and even regions just as effectively as formal diplomacy.

“Influencing or subverting a government is much more tiresome and risky than lobbying Congress to create incentives,” says William Reno, an Africa scholar at Northwestern University in Illinois. “You’re shaping the world that African countries live in based on an ideological assumption that increased trade brings capacity and order, though not particularly transparency. I would question that assumption in states where institutions are weak and governments pursue goals at the expense of these institutions: adding resources (to them) can further empower the wrong things.”

The oil industry is also a major recruiter of government officials who defect to the private sector. Perhaps the ultimate example is the Houston-based Halliburton Company’s decision to hire the current U.S. vice president as CEO in 1996. Halliburton, the world’s largest provider of oil services, has worked in some capacity on nearly every major oil concession in Angola for the past 17 years. Cheney has served three U.S. presidents – prior to becoming vice president to George W. Bush, he was defense secretary under Bush’s father, former President George Bush, and chief of staff under President Gerald Ford. During his tenure, Cheney helped boost the company’s annual profits to $15 billion, doubling its contracts with the Defense Department he once oversaw to $657 million in 1999. Halliburton’s campaign contributions also increased 43 percent under Cheney, an outspoken critic of sanctions. When he was CEO of Halliburton, the company lobbied against sanctions in Sudan, Syria, Iran, Libya, Burma, Nigeria, India and Pakistan. Cheney also quadrupled the amount of government financing Halliburton received from the U.S. Export-Import Bank, the agency tasked with finding new markets for U.S. companies.

Vital Interests

On Feb. 26, 2002, Angola’s President Dos Santos and an entourage of government ministers descended on the downtown Washington Monarch Hotel for a dinner in his honor organized by the Corporate Council on Africa business group and sponsored by BP,

ChevronTexaco, ExxonMobil and Ocean Energy. The crowd included executives from more than 20 companies, along with Assistant Secretary of State for Africa Walter Kantsteiner, Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Africa Rosa Whittaker and American diamond magnate Maurice Tempelsman.

The event, which kicked off a three-day visit with Bush administration officials and oil executives, occurred four days after UNITA leader and Dos Santos nemesis Jonas Savimbi was killed in a skirmish with Angolan government forces. Though diners whispered that Secretary of State Colin Powell had warned Dos Santos that his last excuse for funneling money away from the civil sector was now gone, the warmth of the reception demonstrated that the diplomatic and corporate worlds were willing to embrace him in exchange for stability.

West African oil has always had its boosters, generally confined in the past to a group of congressmen who supported increased African trade and investment across the board. But since Sept. 11, calls for increased attention to the region have found new resonance. On June 20, 2002, the House of Representatives’ Committee on International Relations held a hearing on “oil diplomacy,” at which speakers, including Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham and energy industry analyst Daniel Yergin, echoed each others’ calls to reduce U.S. dependency on politically volatile oil producers and strengthen relationships with non-OPEC countries. One week earlier, an ad-hoc group called the African Oil Policy Initiative Group, drawn from the worlds of government, academia, think tanks and business, released a report that advocated declaring the Gulf of Guinea an area of “vital interest” to the United States, installing U.S. military sub-commands in the region, and conditioning debt relief on energy sector development, among other recommendations.

New to the debate, however, was the mention of transparency as a concern. “Expectations around the world are changing, and old practices are becoming harder to sustain. Transparency is increasingly being called for,” said Rep. Ed Royce, chairman of the House Committee on International Relations’ Subcommittee on Africa. “The practice of turning a blind eye as oil revenues are misused is not good … for Africans, and ultimately it’s bad business for oil companies. If done right, the development of Africa’s energy resources will improve our nation’s security, benefit our economy, and help lift African economies.”

It remains to be seen whether oil companies – and the U.S. government – adhere to the philosophy of transparency as the Dos Santos regime solicits more money to rebuild post-war Angola and counter spreading famine. The United Nations is trying to raise some $200 million in assistance, but donors have been reluctant to give since the war’s end theoretically freed up Angola’s oil revenues. A September aid pledge of $120 million from the World Bank was accompanied by a caveat that Angola further open its books. Though there are signs of progress – the Angolan Finance Ministry in summer 2002 posted sales on its Web site showing oil production and value figures in 2001 – economists say the move is only one small step toward true transparency.

Meanwhile, the rush toward African oil has only picked up speed: U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell toured Angola and Gabon in September, breaking ground on a new U.S. embassy in Luanda, and Bush welcomed several African heads of state to the United States in September 2002.