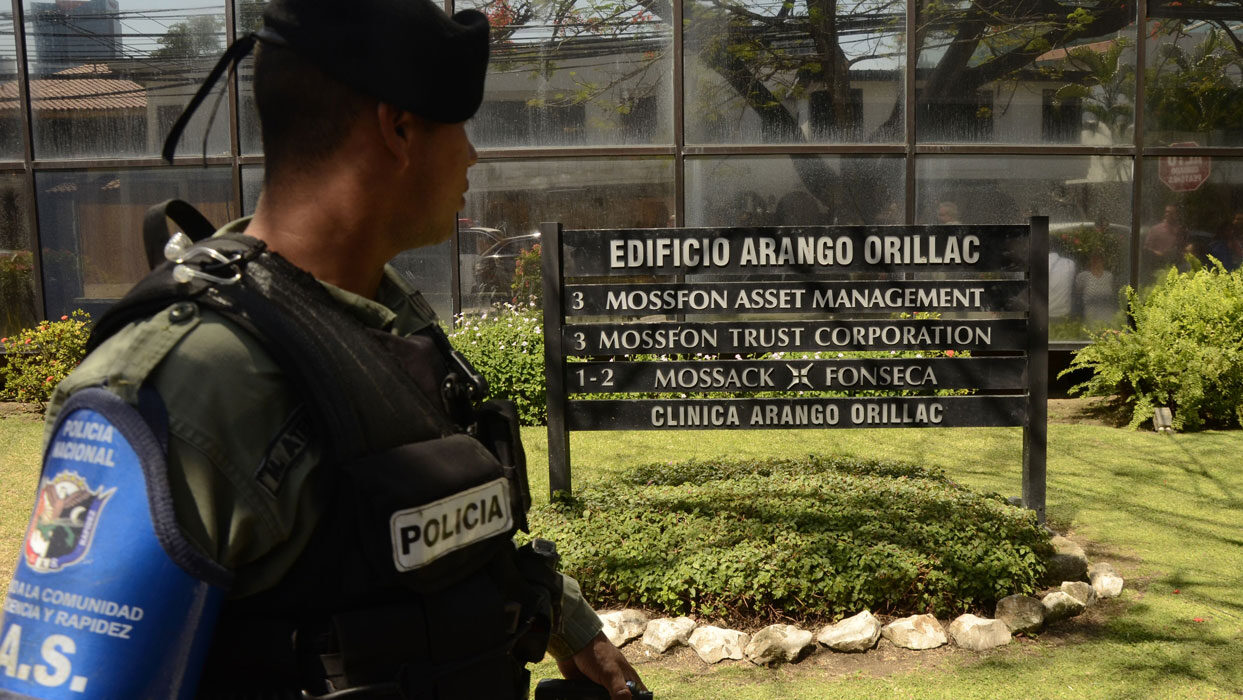

More than a dozen banks will have to turn over details of their dealings with Panama law firm Mossack Fonseca to New York's banking regulator, as authorities continue to respond to revelations from the Panama Papers investigation.

The order came from the New York Department of Financial Services and was sent to 13 foreign banks identified in articles published by ICIJ and its media partners, including Deutsche Bank AG, Credit Suisse Group AG, Commerzbank AG and ABN Amro Group NV, Bloomberg reported.

The banks have been given 10 days to respond, and were asked to provide communications, phone logs and records of transactions between their New York branches and employees or agents of Mossack Fonseca, as well as any subsequent communication with shell companies formed as part of these transactions. According to Bloomberg, the regulator has also asked banks to identify any New York-based personnel who may have held positions at the shell companies.

The regulator is reportedly searching for potential violations of rules or regulations related to the law firm. The banks have not been accused of wrongdoing.

The second ranking Democrat on the U.S. House of Representatives Financial Services committee also used the Panama Papers investigation on Wednesday to request hearings on a bill introduced earlier this year aimed at stopping anonymous company ownership.

Rep. Carolyn B. Maloney (D-N.Y.) cited the Panama Papers investigation in asking for the hearings, and said its findings highlighted “the ease with which criminals and corrupt officials can use anonymous shell companies to hide assets from law enforcement.”

Maloney’s bill, “The Incorporation Transparency and Law Enforcement Assistance Act,” would require corporations and limited liability companies to disclose who their true owners, to the states in which they are incorporated, if the states have such a requirement, or to the Treasury department.

Offshore entities often take advantage of multiple ways in which to make it harder to identify their ownership, including corporate records that make it appear as if stand-ins are actually running the business, or being owned by foundations in jurisdictions such as Panama where the law requires that those involved in setting up the foundation “or any person that obtains information relating to the activities, transactions or operations of the foundation maintain strict confidentiality even following its termination.” Breaches of the law are punished with up to six months imprisonment and penalties up to $50,000.

Earlier in April, Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) asked the U.S. Treasury to investigate any U.S. companies or U.S.-linked companies that appeared in the Panama Papers.

Wyoming, where Mossack Fonseca maintains an office, conducted an audit of firms registered there by the company right after the investigation was published. Secretary of State Ed Murray said that the audit “determined that M.F. Corporate Services Wyoming LLC failed to maintain the required statutory information for performing the duties of a registered agent under Wyoming law.” The information was subsequently provided, he said.

Last week, the IRS participated in a special meeting of the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development’s Joint International Tax Shelter Information & Collaboration Network that was called in the wake of the Panama Papers.

“People hiding assets offshore should recognize the continued changes and progress in the international tax arena” and “come forward voluntarily,” the IRS said in a statement. “The IRS welcomes the OECD’s support of the JITSIC’s work to coordinate the effort by tax authorities across the world to respond to the released information. We will be closely monitoring the situation along with our international tax administration partners as we determine what steps to take to ensure compliance with U.S. tax laws and meet our shared global interests.”