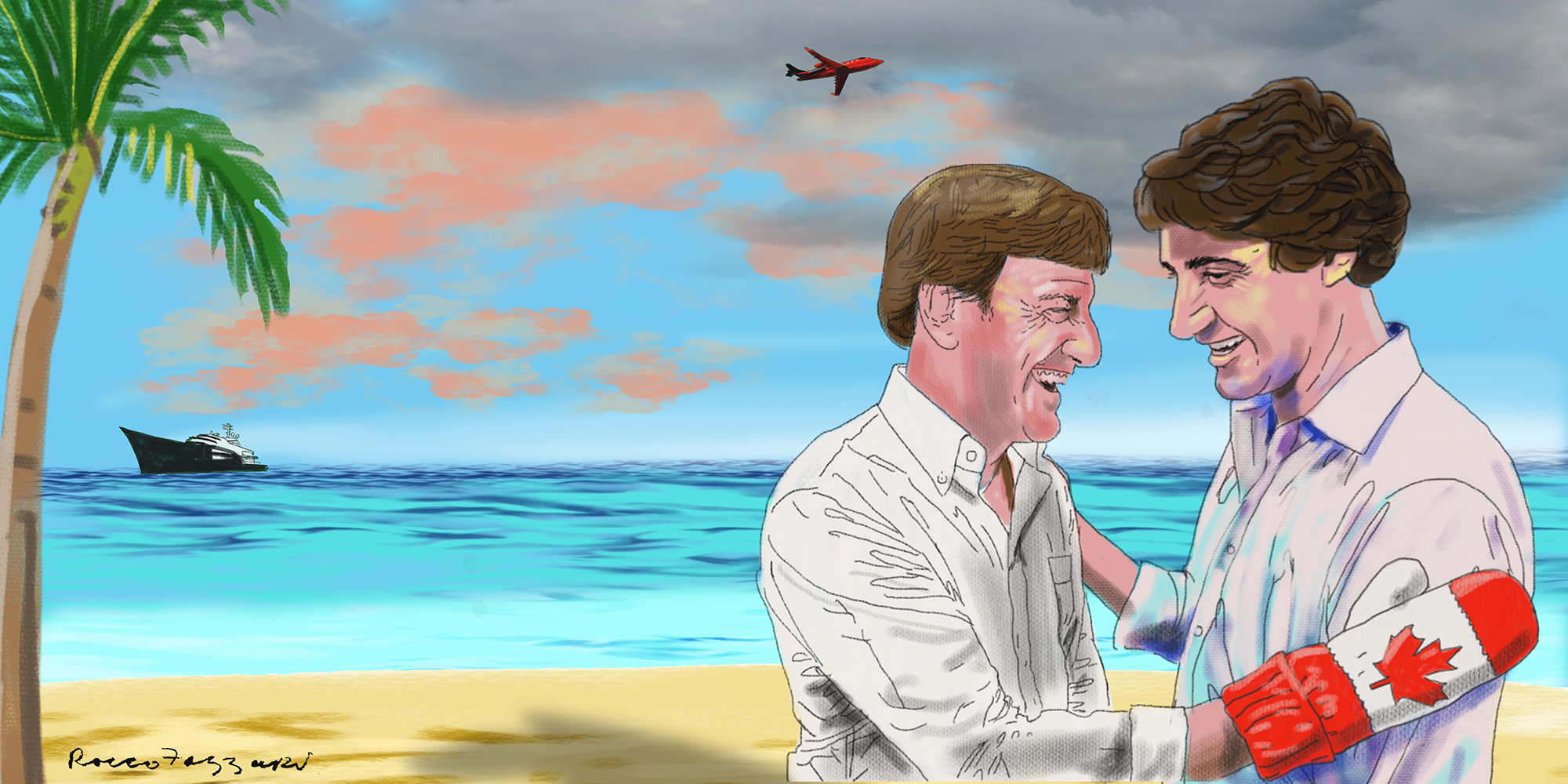

As a candidate and as Canada’s prime minister, Justin Trudeau has made economic and tax fairness a centerpiece of his political message. “We can afford to do more for the people who need it by doing less for the people who don’t,” he said while running for office.

Trudeau had begun his campaign for a new kind of Canadian politics by turning to a close friend to help raise funds for it: Stephen R. Bronfman.

A financier and scion of one Canada’s most famous families, Bronfman quickly transformed Trudeau’s Liberal Party from moribund political pauper to financial juggernaut, nearly doubling donations in two years. As a thank-you gesture, he sent thousands of donors pairs of mittens in Liberal Party-red.

“Justin is very, very salable,” Bronfman, 53, once observed to reporters. “He’s got a great name, and people want to find out who he is.”

As the Liberal Party’s chief fundraiser, Bronfman took on a mantle long worn by his godfather, Leo Kolber, the jokingly self-proclaimed “consigliere” of the Bronfman family and longtime pillar of the Liberal Party establishment. Kolber ran many of the Bronfmans’ businesses for decades, becoming wealthy himself in the process.

But while Trudeau’s tax-the-rich message resonates with admirers around the world, a trove of secret documents suggest that Bronfman’s private-investment company, Claridge, for a quarter of a century quietly helped move millions of dollars offshore to Kolber family entities that may have avoided taxes in Canada, the United States and Israel, via a family trust, shell companies and accounting moves questioned by experts.

Some of those moves may have run afoul of the rules, according to tax experts, and came as lawyers representing Bronfman, Kolber and other clients with offshore interests were credited with leading a lobbying campaign that successfully staved off a crackdown on offshore trusts long sought by Canadian tax officials.

A lawyer representing the Bronfmans and Kolbers told the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. that “none of the transactions or entities at issue were effected or established to evade or even avoid taxation” and that they “were always in full conformity with all applicable laws and requirements.”

Any “suggestion of false documentation, fraud, ‘disguised’ conduct, tax evasion or similar conduct is false, and a distortion of the facts,” he said.

A spokesman for Trudeau declined to comment.

The revelations are found in internal files of the Bermuda-based offshore law firm Appleby that were leaked to Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared with ICIJ, the CBC, Radio-Canada, the Toronto Star, and more than 90 other media organizations in 67 countries. Many of the documents pertaining to the Bronfman loans to Kolber trusts belonged to a trust company in the Cayman Islands called Ansbacher that Appleby acquired in 2006.

Taken together, the documents offer a glimpse of how powerful interests work to protect the offshore financial system for their own benefit.

Power players in Canada

Stephen Bronfman is a grandson of legendary patriarch Samuel Bronfman, a Russian immigrant who built a Canadian business selling liquor that found its way into the United States during Prohibition and turned it into the multibillion-dollar Seagram’s fortune, which was inherited by his sons, Edgar and Charles, when he died in 1971. The Bronfman family bought or built real estate giant Cadillac Fairview Corp., Hollywood’s Universal Studios and Manhattan’s landmark Seagram Building, along with large stakes in MGM and DuPont. Charles Bronfman is Stephen’s father.

The Samuel and Saidye Bronfman Family Foundation, established in the 1950s, was one of Canada’s largest philanthropies, and the family name appears on buildings at McGill University in Montreal and a wing of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. A family biographer wrote in 2016 that “by virtue of their enormous wealth, the Bronfman family were equivalent to Canadian royalty.”

Stephen Bronfman, a rock-music-loving baseball fan, wanted to be a pro skier as a young man rather than a businessman. Ultimately, he inherited control of the family investment firm, Claridge Inc., from his father and ran investments in real estate, restaurants and entertainment businesses. Carrying on the family tradition, he is a major philanthropist who has donated millions of dollars to Jewish, educational and environmental charities. After he raised nearly $2 million for Trudeau’s successful run for Liberal Party leader in 2013, Trudeau picked him to be the party’s chief fundraiser for the victorious federal campaign in 2015.

Leo Kolber, born to modest circumstances, started his career in the 1950s, finding small real estate deals for Samuel Bronfman, and by 1957, he was running the Bronfmans’ private investment firm. “We were fortunate to be influenced by a guy like Leo who had to count his pennies and earn a living,” Edgar Bronfman wrote in his autobiography. A family biographer wrote that “Sam [Bronfman] treated him [Kolber] as a son, while Leo worshipped Sam as a father.”

When Stephen Bronfman was born in 1964, Kolber was named godfather. Kolber helped build Cadillac Fairview and led the development in the 1960s of the landmark Toronto-Dominion Centre. In his 2006 autobiography, “Leo: A Life,” Kolber wrote, “I’ve been a man of some influence and have enjoyed every moment of it.”

In 1983, Pierre Trudeau, Justin’s father, who was then finishing his tenure as one of Canada’s longest-serving prime ministers, appointed Kolber to the Canadian Senate. “How often do I have to go?” Kolber asked. “Just show up once in awhile,” Pierre Trudeau responded. “It’s no big deal.”

The next year, Trudeau’s Liberal successor, John Turner, appointed Kolber the party’s chief fundraiser. Kolber flew around Canada on the Bronfmans’ jet, raising millions for the party and eventually adopting another joking nickname, “the Bagman.”

Over the years, the Kolber family finances became intertwined with those of the Bronfmans. When Charles Bronfman set up a branch of the Claridge investment firm in Israel in the early 1990s, Kolber’s son, Jonathan, moved there to run it in exchange for 15 percent of the business, according to Ansbacher documents.

An interest in taxation

Despite his seemingly casual approach to the Senate, Kolber took strong stands over the years on behalf of financial interests. He pushed for years to make bank mergers easier, for instance, and ascended to the chairmanship of the Senate Banking Committee. He was a major factor in measures to cut Canada’s capital-gains taxes.

During his time as an influential political figure, Kolber, along with his son, Jonathan, moved assets offshore, with help from the Bronfmans. According to leaked Ansbacher records, Leo Kolber set up the Kolber Trust in 1991 in the Cayman Islands to hold those funds, naming Jonathan Kolber and his “legitimate issue” as the trust’s beneficiaries. Millions of dollars in loans from the Bronfmans helped fund the Kolber Trust in its first months, the records show. The first, a $9.7 million loan from Charles Bronfman in May 1991, contained an unusual provision: “The Loan shall bear interest at such rate as may be determined between the parties from time to time.”

By the mid-1990s, the Kolber Trust held $38.5 million in assets, according to Ansbacher documents, and its activities were entwined with the Bronfmans’ via financial advisers, lawyers, and loans, mostly from Bronfman trusts to the Kolber trust.

In 1996, Canada’s then-Auditor General L. Denis Desautels put the issue of tax fairness on the public agenda when he released a blockbuster report detailing an unusual 1991 ruling by the Canada Revenue Agency that had allowed a wealthy family, which the report did not identify, to move 2 billion Canadian dollars out of the country untaxed.

The report concluded that “the transactions may have circumvented the intent of the law” and that the ruling had deprived the treasury of hundreds of millions of dollars. It also revealed that senior officials had overruled agency staffers who opposed the decision.

I think every step of the way the big financiers in this country, the wealthy families, the corporations that benefited from these tax havens just kept the pressure on the government, and many times they were the government.

Desautels never revealed the identity of the family, but press reports did: Charles Bronfman and his children, Stephen and Ellen.

In a recent interview with ICIJ partners CBC and Radio-Canada, Desautels said he was also concerned at the time that legal representatives for the family had special access to government officials. He still declined to name the family.

With public pressure building for tax reform, Canada’s Department of Finance in 1999 introduced measures to shut down “abusive” offshore trusts — vehicles used by wealthy Canadians to avoid taxes at home. Officials wrote that rules curbing trusts were easy to circumvent and that several tax havens were helping wealthy families conceal income that would normally be subject to Canadian taxes.

But under pressure from lawyers and lobbyists, the Liberal government in November that year abruptly backed down from its own proposals.

“I think the government was very clever at being able to show concern about the issue but all the while do nothing,” recalled Judy Wasylycia-Leis, a former member of Parliament who sat on the House of Commons Finance Committee. “I think every step of the way the big financiers in this country, the wealthy families, the corporations that benefited from these tax havens just kept the pressure on the government, and many times they were the government.”

Records from Canada’s Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying show that lawyers representing Bronfman trusts lobbied government officials on legislative efforts to tax income from offshore trusts or otherwise crack down on their use for tax avoidance. In 2005, for instance, Michael Vineberg of Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg, the law firm for both the Kolber and Bronfman trusts, registered to lobby on behalf of Bronfman trustees.

The documents show that over the years, Appleby took note of lobbying efforts in Canada to stop such a crackdown. “Various groups are lobbying the Canadian government in an effort to get this proposal scrapped, but at this time there is no assurance that this will be successful,” an Appleby managing director said in an internal email in 2008. “We therefore need to identify potentially affected cases and take steps to amend the terms of the trust where possible.”

By 2008, Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg was hailed by a trade newsletter as having played a critical role in stopping, in the Canadian Senate, offshore-trust legislation that had passed the House of Commons. “This level of review from a body [the Senate] that has traditionally rubber-stamped legislation is likely unprecedented,” a Canadian tax attorney wrote at the time, adding that “the torch has been carried” by lawyers at Davies Ward.

Canada’s law cracking down on offshore trusts wouldn’t be enacted until 2013.

The Kolber Trust

Appleby records reveal unusual agreements over the years between the Kolber and Bronfman trusts. The files show, for instance, that some of the Bronfman-to-Kolber loans were made without interest.

Tax agencies, including the Internal Revenue Service and the Canada Revenue Agency, view no-interest loans between related parties as possible red flags for tax-avoidance schemes that disguise taxable earnings or gifts as loans.

Reuven Avi-Yonah, a law professor at the University of Michigan who runs its international tax program, said tax laws generally bar such transactions: “You can’t have interest-free loans between related parties.”

In 2004, the Bronfmans and Kolbers had a problem with one particular non-interest-bearing loan for $4.1 million. Documents show the U.S.-based Bronfman trusts were required to charge interest and did so.

The same year, Jonathan Kolber got an email from his investment adviser, Don Chazan, who said that, although the Bronfmans’ trusts were required under American law to charge interest, it was Claridge’s “intention to ‘make you whole’ somehow.”

Chazan wrote that “perhaps, you will be asked to invoice Claridge a fee for services rendered, equal to the interest which Claridge has charged [Kolber Trust] on these loans.”

In a 2005 email, Chazan wrote to Kolber, “As there was never supposed to be interest paid on this debt in substance (only in form), the [Kolber Trust] needs to be compensated by the Bronfman trusts for these cash outlays.” Jonathan Kolber faxed a copy of the email to his lawyer in Israel and marked it “CONFIDENTIAL!!”

Kolber’s and Bronfman’s lawyers said the loans received by the Kolber Trust “were at arm’s length” and that “non-interest bearing loans by a U.S. person do not violate U.S. law. Rather, in certain circumstances, there is a deemed interest concept.” Deemed interest, also known as imputed interest, is interest that is treated for tax purposes as if it has been paid even if it hasn’t.

“With respect to the emails from Mr. Chazan, no invoices were sent and nothing was paid,” the lawyers said.

“One less formal link”

The documents also show that Kolber’s representatives were concerned about leaving a paper trail of connections between the trust and its operations in Canada. The Canada Revenue Agency says that a company’s or trust’s true location — regardless where it is incorporated — is where its “mind and management” are based. If Canada’s tax authorities find that an offshore trust was in fact run from Canada, it can be liable for taxes dating back to its founding.

A 2006 internal memo in Ansbacher’s files about a recent conversation its lawyers had had with Chazan noted a $81,750 invoice for his services might tie the trust’s management to Canada. Chazan’s work “should be treated as personal expenses and not expenses of the trusts,” wrote an accountant at Ansbacher. “This results in one less formal link between the trusts and entities outside Cayman (in the case of the Kolber Trust).” Ansbacher later accounted for the $81,750 paid to Chazan as a “loan repayment” to Jonathan Kolber.

In an interview with the CBC several weeks ago, Jonathan Kolber was asked who had run the Kolber Trust. Kolber responded that Chazan “was the adviser. He’s the guy who made the decisions.” Chazan is based in Montreal.

In response to ICIJ’s questions more recently, however, the Kolber and Bronfman lawyers said: “The Trustee who manages and administers the Trusts and makes all investment and other decisions has always been Cayman Islands residents or trust companies who are proficient and experienced in the management and administration of trusts,” adding that “Mr. Chazan’s services were rendered principally in the Cayman Islands. He was certainly never the directing mind of the Trust.”

“Mr. Chazan issued invoices to Jonathan Kolber, rather than the Kolber Trust, as he was engaged by Jonathan Kolber, not the Kolber Trust, to confirm that all financial transactions of the Kolber Trust had been properly recorded,” the lawyers added. “The Trustee had its own accounting department…Even in the event that Mr. Chazan would have rendered accounting services to the Trust, and have rendered such services in Canada, neither of which was the case, the central management and control of the Trust would still not have been in Canada.”

In an interview, Chazan declined to go into detail about the matter, saying he wasn’t authorized to discuss it.

In 2007, the Kolber Trust had another issue. Lynne Kolber Halliday, Jonathan’s sister, was also a beneficiary, but because she was a U.S. citizen, her trust distributions triggered American taxes.

“Removing the US beneficiaries from the trust was the best way all round of dealing with the estate planning of the parties involved,” Appleby wrote. Halliday’s name was then taken off the trust. Appleby later created a second trust for the family to take care of “tax questions that arise or may arise in” the Kolber Trust.

Halliday “would be taken care of in other ways than through the trust,” Appleby wrote, adding that “Jonathan will arrange to make gifts to her instead of the trust making the present distributions to her.”

“This looks like an attempt to circumvent what would ordinarily be her income tax liability on direct distributions from the trust,” said Grayson McCouch, a trust law professor at the University of Florida.

“Jonathan Kolber was (and remains) a successful Israeli businessman and wished to assist his sister,” the Kolber and Bronfman lawyers said. “Personal gifts are a customary mode of financial assistance. The receipt of gifts is non-taxable in the United States. Jonathan Kolber made gifts to his sister who is an artist and a writer.”

In a later letter, the lawyers said that after 2006, “no gifts were made by Jonathan Kolber to Lynne Kolber Halliday and no distributions were made to her from the Kolber Trust.”

By 2014, Appleby documents show a change in tactics by the Kolber trusts. “We are having serious discussions about the future of the Trusts in light of recent tax changes in Israel,” Jonathan Kolber wrote to Chazan. Kolber’s attorneys proposed a settlement with the Israel Tax Authority the following year. An agreement was reached, said Jonathan Kolber in the interview with the CBC. The amount of the settlement could not be learned.

Stephen Bronfman and Leo Kolber declined to comment. Lynne Halliday did not respond to requests for comment.

A lawyer for Jonathan Kolber and Stephen Bronfman said in a statement that the Kolber trusts were not “liable to Canadian taxation” and that they “were always in full conformity with all applicable laws and requirements.” He added that when Kolber moved to Israel in 1991, “new residents migrating to Israel were recommended to establish trusts to hold assets due to Middle East volatility and political, economic and other uncertainties.”

Justin Trudeau on offshore

Since Trudeau became prime minister in 2015, his populist campaign for tax fairness has had its ups and downs. Days after ICIJ and partners published the Panama Papers project, last year’s investigation of the global offshore financial system, Trudeau made a point of noting that his budget had added more than $310 million in funding for the Canada Revenue Agency to bolster Canada’s tax-avoidance fight. “What we’ve seen with the release of the Panama Papers is that there are certain very wealthy individuals who’ve managed to find workarounds that avoid them having to pay their fair share of taxes,” he told reporters.

Two months later, a Liberal-led committee in Parliament scrapped an unrelated probe into what the Canada Revenue Agency called an offshore tax “sham” by the accounting giant KPMG that helped wealthy Canadians avoid taxes by using shell companies on the Isle of Man. KPMG lawyers had argued that the company’s witnesses shouldn’t be made to testify in Parliament because the matter was the subject of an ongoing court proceeding, and the committee agreed. That same month, Trudeau appointed a KPMG executive to be his party’s treasurer, prompting conflict-of-interest allegations from an opposition leader and an ethics watchdog. The case is pending.

A cocktail party

At a black-tie gathering in Germany this year, Trudeau addressed the global backlash against the rich. “It’s time to pay a living wage. To pay your taxes,” he said. “And when governments serve special interests instead of the citizens’ interests who elected them – people lose faith.

In September 2016, Stephen Bronfman helped host a $1,500-a-ticket fundraiser for Trudeau in Westmount, an English-speaking suburb of Montreal that is one of the wealthiest enclaves in Canada. A Liberal fundraiser lured potential donors to the cocktail party by emailing them about the opportunity to “form relationships and open dialogues with our government.”

Derided later by the press as a “cash-for-access” party, it was held at the home of Leo Kolber.