I came to the National Press Club in the hope that Wilbur Ross would solve a puzzle for me – and left little the wiser but with the image of a cookie, iced in tribute to the U.S. Commerce Secretary, imprinted forever on my mind.

For the Paradise Papers investigation last year, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists reported on Wilbur Ross’ business ties to Russian oligarchs, including President Vladimir Putin’s former son-in-law, Kirill Shamalov.

Our story found that as Commerce Secretary, Ross had kept a stake in a shipping company that earned tens of millions of dollars each year from a Russian energy firm with close connections to the Kremlin.

While the facts of the story were undisputed by Ross’ spokesman, I still puzzle over an unsolved question: why would a man estimated at $700 million, who divested from 80 companies in order to join the cabinet, keep a stake worth only a tiny fraction of his overall wealth in a company tied to the world’s most politically radioactive regime?

My first shot at uncovering the truth was to be at a half-hour long reception in an airless chamber boldly titled the Winners Room, prior to the Press Club luncheon Ross was scheduled to address.

But 28 minutes in, there was no sign of Ross among the gathering of mid-level trade emissaries and wonky D.C. reporters. It appeared I was not destined to be the winner.

When all seemed lost, a preternaturally-tanned Ross swept in and began to shake hands along a receiving line in quickfire fashion. I, too, won a handshake. But not an answer, before all the guests were promptly dismissed.

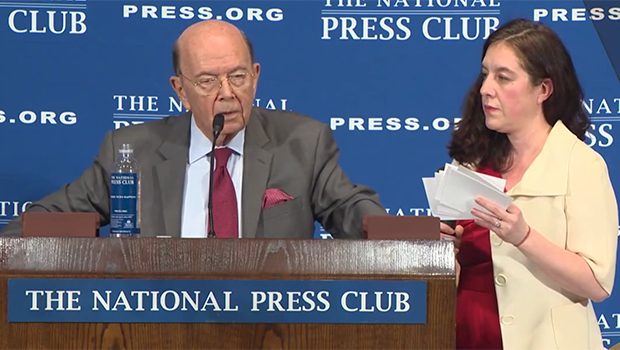

Next, we were directed into a ballroom where Ross would deliver remarks, then take questions from National Press Club president Andrea Edney as we dined on mashed potatoes with beef in curry sauce.

In the middle of our table were the unforgettable treats: cookies iced in honour of Ross with a Magritte painting, the seal of the Department of Commerce and a mysterious coat of arms.

The iced painting, which resembled The Son of Man by the Belgian surrealist, was a tribute to Ross’s $100m Magritte collection. And the coat of arms? The woman next to me said it was the seal of Ross’s secret society in college.

Having documented the cookies for posterity, I refocused on my mission. I had submitted a question to Edney asking why Ross had kept his investment that allowed him to make money from a company partly owned by Putin associate Kirill Shamalov – a man who was among seven Russian oligarchs sanctioned last month by the U.S. Treasury Department – for nearly a year after he became Commerce Secretary.

As Edney inquired in detail about tariffs on China and the European Union, I began to doubt whether my inquiry would see the light of day. But finally, once the subject of trade wars had been exhausted, she asked my question.

As the only question of the day related to his personal finances, it prompted a brief and awkward pause. A look of irritation flashed across the Commerce Secretary’s sun-kissed face before he launched into his answer.

“The Office of Government Ethics did not require the sale of these holdings,” Ross began.

He added that he had divested from the shipping company that did business with Shamalov’s firm before the sanctions on Shamalov were announced. Therefore, he concluded, there was no problem.

“Prior to April 8 there were no sanctions on that company, so there was no reason not to hold it,” Ross said.

Ross’ statement was notable in two ways. It appeared to mistake some of the details: although Shamalov was personally sanctioned, the energy company that Shamalov partly owned, Sibur, was not. And during the time Ross stood to make money from Sibur, the owner of an even larger percentage of Sibur, oligarch Gennady Timchenko, was already on the sanctions list. So the distinction between current and past situations was unclear.

More broadly, his comments contrasted with the remarks and actions of career State Department officials who had initially imposed sanctions on Russia after its 2014 invasion of the Crimea. Daniel Fried, the top U.S. sanctions policy official at the time, described bending over backwards to avoid even the appearance of a conflict of interest when serving the government, particularly in relation to Russia.

“Why would any officer of the US government have any relationship with a Putin crony?” Fried asked.

Ross’ answer that there actually was “no reason” to drop his shipping investment didn’t fully solve the mystery, but it offered insight into my longstanding question of why he had kept his shares.

He wasn’t breaking any laws – and nobody was going to stop him. That, it seems, is how the Ross cookie crumbles.