West Africa Leaks was the largest-ever collaboration of journalists from West Africa.

ICIJ, in collaboration with the Norbert Zongo Cell for Investigative Reporting in West Africa (CENOZO) and more than a dozen reporters from 11 countries, spent months analyzing the 27.5 million documents that represent years of ICIJ data leaks: Offshore Leaks, Swiss Leaks, Panama Papers and Paradise Papers.

A film crew from Al Jazeera’s The Listening Post followed the investigation as it unfolded, and have now released a short documentary that goes deep behind the scenes of West Africa Leaks:

And here, CENOZO coordinator Daniela Q. Lépiz reveals the challenges and triumphs of the collaborative effort. This story was originally published by the Global Investigative Journalism Network, and has been made available under a Creative Commons license.

Under near-constant sunlight and unbelievable heat lies a region filled with minerals and natural resources strategically positioned between Europe, America and the Middle East. Hundreds of companies make billions of dollars a year here and foreign governments invest in development. Yet there are few resources available for West Africa’s citizens.

Those who visit West Africa are immediately hit with a striking reality: inequality is everywhere. Money and business float in the air, yet the vast majority of the population lives on $2 a day. Where is all their money going? Well, the answer, we all sort of know: tax havens.

The offshore industry is a perfect example for tackling these sorts of issues, and its impact in our region is obvious.

But we are not only talking about foreigners — the well-oiled industry of the offshore economy is carefully covered in layers of secrecy with a mantra of “everybody does it” — and indeed many West Africans do.

As the recently launched investigative center for the West African region, CENOZO — the Cell Norbert Zongo for Investigative Journalism in West Africa — aims not just to support investigative journalism but to contribute to the coverage of important local issues, tackling bad governance, corruption, human rights violations, organized crime and terrorism.

Also acting as a contact point for individual journalists as well as various journalism networks interested in covering West Africa, CENOZO was formed by West African journalists with a desire for a global reach — because what happens in West Africa often has global impact.

The offshore industry is a perfect example for tackling these sorts of issues, and its impact in our region is obvious. Among the series of #WestAfricaLeaks stories, we were able to reveal the political elites’ secretive bank accounts, including a longtime friend of Liberian ex-president Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, a Malian presidential candidate and the mayor of the Ivory Coast’s richest city, as well as identify powerful international companies like the Canadian SNC-Lavalin, who used offshore companies to avoid taxes in Senegal.

Logistics of a cross-border collaboration

Will Fitzgibbon, African partnership coordinator with ICIJ, had been following CENOZO’s development. ICIJ wanted to do a West African project — a definitive analysis of all its offshore leaks, but focused only on the region. It was the first time ICIJ would focus on a region-specific investigation, and CENOZO would be the partner.

Of course, Fitzgibbon knew the data well — he had been working with it for four years. But he also knew that local journalists would be able to dig far deeper into solid local angles and point out specific people of interest. We reached out to our donors for help — the Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA) — and we gave it a go.

We organized a training session for our journalists in Dakar, Senegal, bringing together our team in an unprecedented way for the region. The collaborative effort was based on a simple premise: we come together and build a network as well as a bond of confidence. And then we start digging into the stories.

Part of the training involved delving into various encryption methods for communication and accessing the offshore data so we could work securely. With Fitzgibbon in the room, we had an expert to help us understand the data and the complicated offshore world.

After a three-day meeting, our 13 journalists went to their home countries to further analyze the possible leads and each chose one story to focus on. Then, Fitzgibbon traveled across the region to assist with on-site research.

Designing the workflow

With three languages — English, French and Portuguese — and 11 countries to tackle, we set out to find the right experts to help further support the development and vet the legal issues of the stories. French editor Philippe Rivière, libel expert Heinrich Bohmke, lawyer Élise Le Gall and Lisbon-based editor Filomena da Silva were among those who joined the team.

The procedure was clear: editors worked with reporters, advising on new angles and people to contact and identifying places for possible improvements and stronger storylines. First drafts would be submitted — but what was purposely saved for the very last was contacting the people and companies who would feature in reporters’ stories. Everyone on the team had to stick to the rules — no discussing the story with sources who might get suspicious and compromise the investigation, risking losing the entire string of stories which were based on the ICIJ data.

Once editors received the draft stories, Fitzgibbon — now back in Washington, D.C. — helped with calls when officials refused to answer calls from West African numbers.

Once the drafts had their sourcing nailed down, articles were passed on for legal screening. We needed to be certain that the stories did not incriminate anyone without documented foundation and that each journalist was protected by the demonstration of due diligence in their reporting.

Protecting the journalists

One of CENOZO’s missions when we first launched last year was to provide a platform for journalists who could not use their own name for security reasons or who could not publish with newspapers that did not want to publish sensitive stories — a common difficulty in reporting in the region. We faced both situations in #WestAfricaLeaks.

Thanks to the support of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), we developed a website that enables our members to publish articles with CENOZO as a protective structure, using the organization byline for stories and protecting the identity of the journalist who reported some investigations. Indeed, some of the articles for the #WestAfricaLeaks ran without bylines.

Our Burkina Faso-based journalist explained the motivation behind forming the organization: “It all started with a challenge to show that a new type of journalism is possible in our region. That we have investigative journalists and that what we needed to be successful was access to solid documents in order to work. For my story, the biggest challenge was being able to publish in our national paper or on the internet. There were times when my publisher had to make the calls to sources himself so as not to disclose my position and identity to the people I was writing about.”

The pressure our journalists came under was not unexpected. Calls were made to publishers to attempt to stop publication of stories and the threat of pulling advertising were just two of the tactics used. In one case, we experienced something that had the whole team on alert.

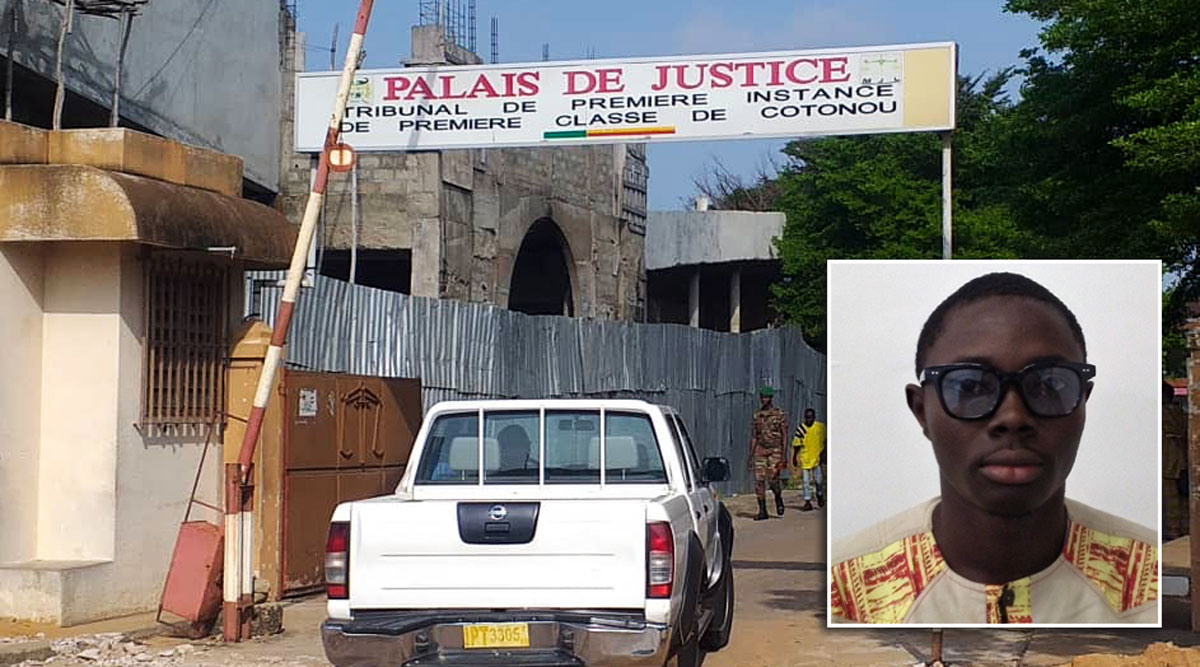

One of the countries involved in #WestAfricaLeaks has very strict media defamation laws, so when the subject of a story threatened to sue a CENOZO reporter, we jumped into action. All articles had been carefully checked by lawyers, but we couldn’t take any chances. We contacted a well-known local lawyer to look deeper at the specific article from the national perspective. The day before publication, we received his reply: “You can publish.”

We were also in constant communication with a member of the Committee to Protect Journalists, keeping him updated on possible conflicts in each one of the countries. In a volatile region where media freedom is not exactly granted, we needed to be sure our journalists were protected. Thankfully, no further intervention was needed.

More still to come

CENOZO is proud to be a platform on which West African journalists can tell their own stories — stories no one knows better than they do. It is a way to say “we are present and ready” to the world — ready to join the wave of innovation in the field of journalism and in supporting transparency and accountability. This was our first project published, but there are many more to come.