This story has been republished with permission from The Irish Times.

In April 2018, I traveled to Washington, D.C. for a secret meeting hosted by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, the group behind the Panama Papers, Swiss Leaks, the Paradise Papers and other investigative journalism projects.

The meeting was an early-stage discussion of a proposed new investigation, the Implant Files, which would look at the ever-growing phenomenon of implanted medical devices, the adequacy or otherwise of their regulation, and the idea that multinational manufacturers might sometimes have too much influence on hospitals and clinicians.

By the time the fruits of our labors were published on Nov. 25 last year, more than 250 journalists around the globe had become involved.

And in the period during which we were researching our project, three of the journalists had a medical device implanted – including yours truly.

The story of my personal engagement with the world of medical devices began on the weekend of the 2018 October bank holiday, when myself and a few others decamped to the marvelous Glenmalure Inn, in the Wicklow mountains in Ireland’s east.

On the first afternoon, we set out on a two-to-three hour circular walk. I let the others go on ahead and then hurried after them about half an hour later.

Hurrying alone up a steep path through a wood, I felt a strange sensation in my chest which I wouldn’t quite describe as pain. The sensation was odd enough for me to pause and reflect, but not so severe that I was persuaded to turn around and go back to my room.

When I caught up with the others, and we entered the level stretch of our walk, the sensation disappeared.

The next day, having had a good meal washed down with stout and red wine the night before, we went again on the same walk. I wasn’t hurrying this time but again I had an unpleasant feeling in my chest while on the upward stretch. The same proved true on the third day. The following few days I noticed a milder version of the same sensation while cycling up slopes on my way home from work.

From warning signs to a heart ‘something’

The following Monday I went to my doctor, who told me not to proceed to work as was my intention, but rather to go to the cardiac unit in the Mater Private, on Dublin’s Eccles Street, which I did.

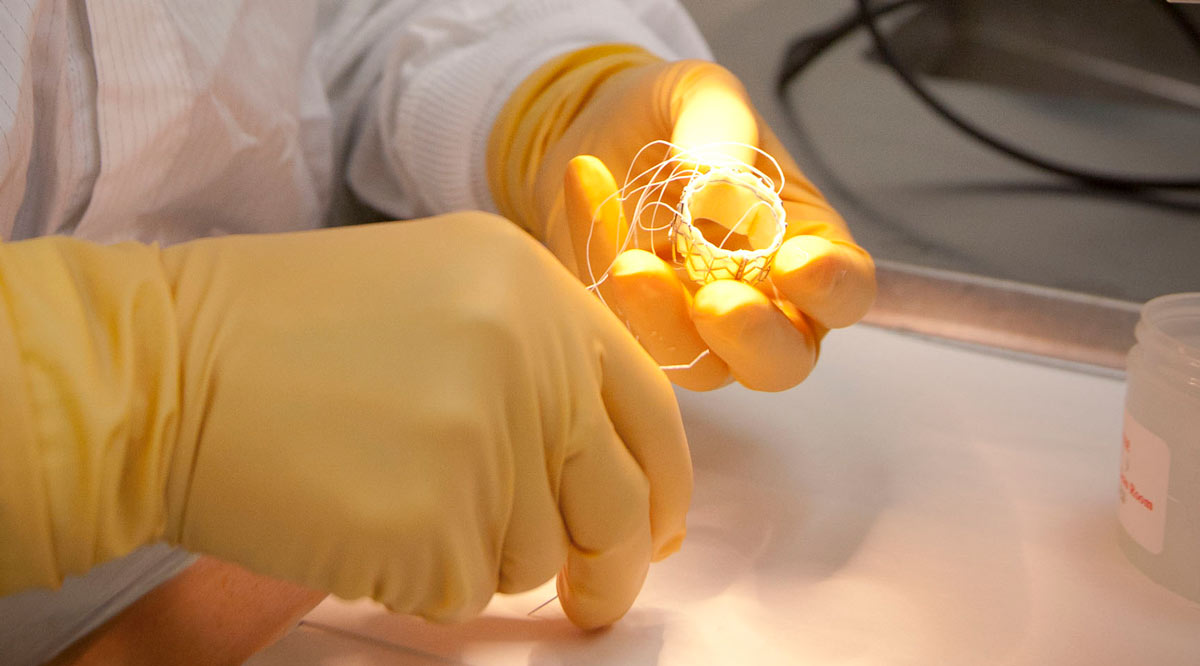

A blood test showed enzymes that were indicative of a heart something, and so I found myself on my way to a catheterization or cath lab, having agreed that should the surgeon find anything untoward, he had permission to put in a stent.

For those who don’t know, cath labs are where you go for heart investigations. They are extraordinarily wonderful places in that the people there do their work without cutting you open.

One of my arteries was 80 percent blocked, so the surgeon put in a stent … I resisted the impulse to take notes, or ask too many questions.

My surgeon and his team were able to put a “wire” into one of my arteries, going in at the wrist, and then shove it up the artery until it was at or inside my heart. They then monitored on an X-ray screen the flow of some inky substance they puffed up through the device.

One of my arteries was 80 percent blocked, so the surgeon put in a stent using the same up-the-artery-in-the-arm device. There was no pain but there were some truly odd and unpleasant sensations.

The whole procedure was over within less an hour, as best as I can recall. You stay awake though they do give you a shot of something to keep you calm. I resisted the impulse to take notes, or ask too many questions, though I did find out later that I was now the proud carrier of a Boston Scientific Synergy 4.0mm stent.

I was kept in overnight and was the youngest of the four males in my ward. When my partner and my three children came in for a short visit, it was not clear to me who was the most surprised by the strange turn the day had taken. I felt quite shaken for weeks afterward.

Seeing implants in a new light

Over the years I’ve been told a few times that my cholesterol levels were on the high end. I don’t smoke, am fit enough for my age, and have a reasonable diet. My parents lived to their nineties. I was told in the hospital before being discharged that some people just produce more cholesterol than others, and given a prescription for statins.

I went back to my doctor a few days afterward and thanked her for sending me straight to the Mater. When asked, she told me that if I’d presented in hospital as a public patient I might have had to wait in the emergency department as I had no symptoms at the time, but eventually a blood test would have been taken, and once the enzymes were noticed I would have had an angiogram, followed by a stent, all by late that evening.

That was a cheering piece of information.

The experience certainly cast the meeting I attended in Washington, D.C. last April in a new light. But the core reasons for the project remain valid.

The importance of medical devices in saving lives and treating chronic conditions is ever-growing, as are the wonders and sophistication of the devices being developed.

There are genuine reasons for being concerned about the quality of the sector’s regulation as matters stand, and the size of the challenge for the regulators is only going in one direction.

The Implant Files project highlighted the extent to which people in developing countries are dependent on the quality – and level of transparency – of the regulatory regimes in the EU and the U.S.

There is also no doubt but that we need to keep a close eye on whether the multinational businesses that are behind the great inventions that are so improving healthcare outcomes are getting too great a say in what goes on inside hospitals and healthcare systems generally.

But all of that said, there is no denying the wonders of the sector’s achievements. It is a huge part of Ireland’s economy, and accounts for almost ten percent of the country’s exports. Eight out of every ten stents are manufactured in Ireland.

The phrase “made in Ireland” is now closer to my heart than it was when I visited Washington, D.C!