In the summer of 2017, U.S.-based private prison company GEO Group was preparing to massively expand an immigration detention complex in Conroe, Texas, a small town not far from Houston.

For months, I had been reporting on harsh conditions that immigrant detainees face in isolation cells in these facilities, often operated by private contractors under the direction of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). As ICE’s network expanded, I wanted to know exactly how many new solitary confinement cells would be appearing in Conroe — one of the first detention centers to be built under the Trump Administration.

In late July of 2017, I sent the city of Conroe a public records request asking for blueprints of the facility, which the GEO Group had given to the city’s building inspection department. Such requests use state or federal laws to compel government agencies to disclose documents deemed to be public. I thought it would help shed light on the agency’s future use of solitary confinement if I could see how much space it was devoting to the cells in the new facility.

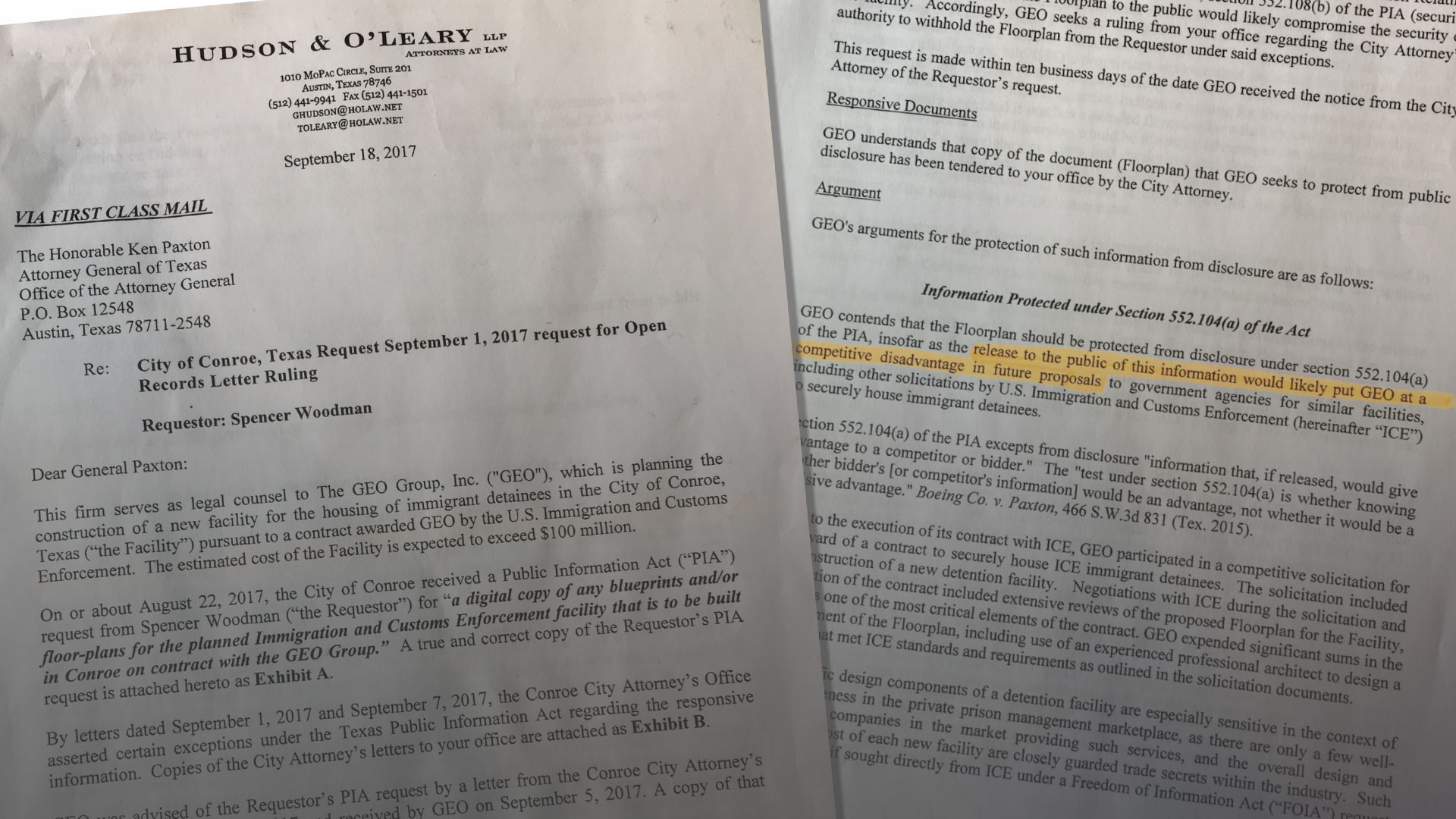

But I got nowhere. First, I received a brief letter from the city of Conroe rejecting my request based on “copyright laws” governing the records — though I would be allowed to view the blueprints in person if I could travel to Texas from New York, I was told. A few weeks later, I was surprised to find a hefty envelope in my mailbox from Hudson & O’Leary LLP, a private law firm hired by the GEO Group.

The letter inside, originally addressed to the Texas attorney general, made a full-throated legal argument against the public release of the blueprints. The main contention: that doing so could hurt the company’s bottom line. “The release to the public of this information would likely put GEO Group at a competitive disadvantage,” the letter stated. It included a lengthy appendix laying out the case law behind the GEO Group’s claim, which was based on a “trade secret” exemption to public records law.

The law firm’s letter was a testament to both the extra layer of secrecy that private contractors can add to government — and to the substantial firepower such corporations wield in fighting against journalists seeking information about how tax dollars are being spent.

“It’s a growing threat,” Aaron Mackey, an attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told the Committee to Protect Journalists earlier this year on the increasing reach of exemptions based on the claim that releasing records would spill confidential business information. “It could start getting in the way of basic reporting.”

The public interest imperative in pursuing this story was clear. I had spoken with detainees who had spent weeks and even months in isolation for minor infractions, at great cost, they said, to their mental health. Locking a detainee alone in a cell for 22 hours a day or more can lead to panic attacks and suicidal impulses. And eventually, I landed my story: Last May, Solitary Voices, an investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and six media partners into ICE’s misuse and overuse of solitary confinement, was published in May.

Yet the new 1,000-bed facility in Conroe, which was completed late last year, did not factor into our investigation because I never received any information about the new facility.

The law firm made an additional argument: releasing the facility’s blueprint would also endanger the safety and security of facility staff and visitors. While the security exemption is a plausible concern, public agencies have applied it excessively in some cases to block records requests. (In 2017, I won a court case by arguing that the Michigan Department of Corrections had wrongly withheld records under a security exemption.)

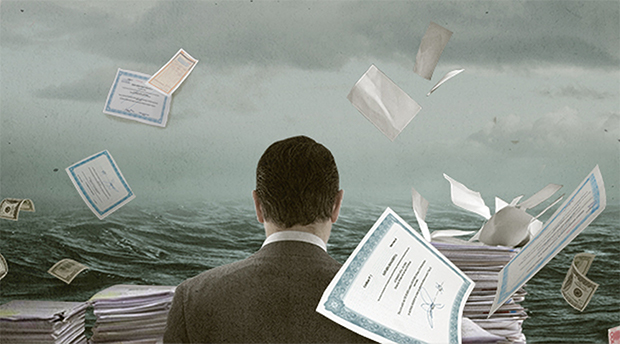

I’m not the only journalist to see a records request to a private company spending public dollars met with impressive force.

As the private sector increasingly intertwines with government, a series of recent reports have examined the growing strength and sophistication of how these firms work with their government clients to help block records requests. Private companies and trade groups have launched extensive litigation to block disclosure of what they argue to be confidential information and have advocated for legal standards more favorable to secrecy. In some cases, companies have even arranged for government officials to sign non-disclosure agreements and to give them advance notice on requests that could encompass business records. (A few years ago, when I was reporting on the ride-share company Uber’s aggressive courting of public contracts in Florida, I learned this the hard way. Before one municipality provided me with records, Uber company reviewed my request and shielded from disclosure what I believed to be crucial information about its volume of rides and revenue).

And the business-secret obstacle to government transparency appears to be deepening. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with an industry group in expanding the definition of “confidential” information that could be blocked from disclosure under federal public records laws.

“The Supreme Court’s ruling could make it more difficult for reporters to pry loose information they need to do their jobs,” Avi Asher-Schapiro, North America Researcher at the Committee to Protect Journalists told ICIJ in an email. “Journalists often rely on documents that private companies submit to the government to break important public interest stories.”

The letter from the GEO Group was ultimately a footnote in my reporting. As reporters do, I made a quick calculation: putting up a fight over the blueprints simply wasn’t worth my time. Although it may have provided a useful data point, it ultimately wouldn’t answer my broader question about prevalence of solitary confinement placements in ICE facilities. Another public records request — this one to ICE itself — proved far more useful: I obtained thousands of records describing the use of isolation at centers across the U.S.

Last month, I decided to ask the GEO Group whether the company could at least tell me how many new solitary confinement cells had been built. Five emails and two voicemail messages to the GEO Group’s press office have so far gone unanswered.

When I tried putting the same question to ICE, which had commissioned GEO to build the new facility, I got nowhere.

“I’m afraid the Office of Public Affairs is not going to be able to assist with your request,” public affairs officer Shawn Neudauer said in an email. My only option, Neudauer said, was to file another public records request for the blueprints.