The business of recycling dead humans has grown so large you can buy stock in publicly traded companies that rely on corpses for their raw materials, a new investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists has found.

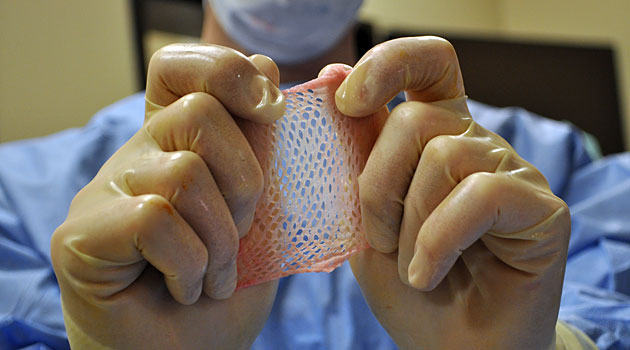

“Skin and bone donated by relatives of the dead is turned into everything from bladder slings to surgical screws to material used in dentistry or plastic surgery,” according to Gerard Ryle, the director of ICIJ, which is a project of The Center for Public Integrity.

Distributors of the merchandise can be found in the European Union, China, Canada, Thailand, India, South Africa, Brazil, Australia and New Zealand. Some are subsidiaries of billion-dollar multinational medical corporations.

ICIJ’s eight-month, 11-country investigation found patients aren’t always told that the product they are getting originated from a corpse. This leads to an even more complex issue – how does the industry source the raw material it uses for its products?

Among our key findings:

• Consent: There have been repeated allegations in the Ukraine that human tissue was removed from the dead without proper consent. Some of that tissue may have reached other countries, via Germany, and may now be implanted in hospital patients.

• Safety: Surgeons are not always required to tell patients they are receiving products made of human tissue, making it less likely a patient would associate subsequent infection with that product.

• Tracking: The U.S. is the world’s biggest trader of products from human tissue, but authorities don’t seem to know how much tissue is imported, where it comes from, or where it subsequently goes. The lack of proper tracking means that by the time problems are discovered some of the manufactured goods can’t be found. When the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention assists in the recall of products made from potentially tainted tissues, transplant doctors frequently aren’t much help.

“Oftentimes there’s an awkward silence. They say: ‘We don’t know where it went,’” said Dr. Matthew Kuehnert, the CDC’s director of blood and biologics. The international nature of the industry, critics claim, makes it easy to move products from place to place without much scrutiny.

“We are more careful with fruit and vegetables than with body parts,” said Dr. Martin Zizi, professor of neurophysiology at the Free University of Brussels.

The ICIJ’s investigation relied on more than 200 interviews with industry insiders, government officials, surgeons, lawyers, ethicists and convicted felons, as well as thousands of court documents, regulatory reports, criminal investigation findings, corporate records and internal company memos.

The ICIJ also conducted analysis on registered tissue banks, imports, inspections, adverse events, and deviation reports filed with the Food and Drug Administration, the U.S. agency that polices the trade.