Sheila Coronel is the director of the Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. Last month, she was named as the next academic dean of the journalism school, a position she will assume in July. Prior to joining Columbia, Coronel founded the Phillippine Center for Investigative Journalism, where her reporting on corruption and graft by then-President Joseph Estrada helped bring about his impeachment and subsequent resignation. She recently spoke with ICIJ for its “Secrets of the Masters” series.

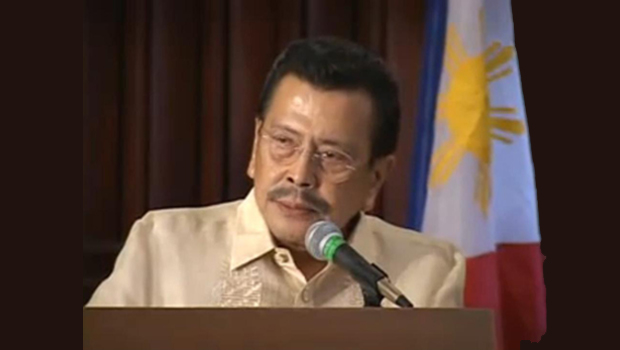

As the director of the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, your reporting revealed the massive personal fortune compiled by then-President Joseph Estrada. How did you report that story and what were your main findings?

That story was fundamentally a way of proving corruption – not by getting evidence of the actual corrupt acts, which was difficult, but by investigating where the proceeds of corruption went. We had heard rumors of large-scale bribery and commissions from government contracts and the sale of shares in state-owned companies. Because it was almost impossible to prove bribery, we decided to go after the fruits of bribery instead.

Estrada was a former movie star who had five mistresses and he was building fabulous mansions in the ritziest parts of Manila for them. None of these properties were in his or his family members’ names. They were registered in the names of shell companies and it was difficult to show real ownership. What we were able to do was establish a pattern in the acquisitions: the same law firms were used to incorporate the companies, the same nominees fronted for the purchases, the same architects were used, the same interior designers, landscape architects, etc. Even the design of the houses was the same because Estrada went home to a different house every night, frequently intoxicated, and so didn’t want to be stumbling in unfamiliar territory.

We also spoke to a number of people, including builders, neighbors, friends and associates who had interacted with Estrada in relation to those properties. We found that Estrada had bought 17 pieces of real estate in just the first two years of his presidency, and we said that based on his income tax return and his financial disclosures, he couldn’t have legitimately afforded them. We also found dozens of companies that had been formed by him and his families, and none of these were disclosed in his asset statement. We discovered thriving business enterprises set up by the more entrepreneurial mistresses and these businesses had assets that could not be explained by the president’s legitimate earnings.

What were the biggest challenges you faced in reporting a story about graft and cronyism by the country’s most powerful politician? How did you confront those challenges?

We had to make sure that our investigation was not just conducted independently but also perceived to be independent of partisan politics. We documented all our record searches to show that we had obtained the information ourselves, it was not leaked to us by political rivals. There were safety concerns as well and we made sure to keep track of each other’s whereabouts, secure the documents and computer files in our office, and that we had legal backup from pro bono law firms. Our stories were very carefully researched and documented. You don’t go against the president unless you can prove each and every fact in your story. We received some indirect threats but we never knew how serious they were.

When you first published your stories, the mainstream media in the Philippines didn’t pick up their findings. But after several months and additional revelations, President Estrada was impeached for corruption and popular protests helped force his resignation. What do you think were the key factors that allowed the information you uncovered to make a difference?

Estrada was a very popular president and the mainstream media were initially reluctant to publish our findings. Moreover, he was quite vindictive against critical news outlets – he initiated an advertising boycott, and eventually a buyout, of a newspaper that had published allegations of shady deals involving the presidential palace.

What turned the tide was the revelation by one of Estrada’s buddies that the president was receiving money from illegal gambling. There was a feud in Estrada’s inner circle – factions were angling for control over gambling payoffs. This guy lost out and feared his life was in danger. He made the revelations to save his skin. The public was understandably hungry for more information. By then, we were ready – we had been researching Estrada’s wealth for a year and we couldn’t roll out the stories fast enough. They went viral, picked up by newspapers, radio and TV.

Our reporting made a difference because it was nonpartisan and based on documented evidence. Our stories on presidential excess also struck a chord among citizens. Estrada had projected this image that he was a man of the masses. Our reports unmasked him for what he was. They captured the popular imagination – they were sensational, you know, millions, mansions, mistresses. This kind of excess was easy to understand; it also generated a great deal of popular outrage, especially among the middle class, the business community and the Catholic Church.

Soon, there were demonstrations in front of the houses we had uncovered. Congress convened an impeachment court, but when it looked like the court was being compromised, hundreds of thousands massed in protest, refusing to leave until Estrada resigned, which he did.

What is the path that led you to investigative journalism in the first place?

I started journalism during the Marcos era, when the press was heavily controlled. I had experienced censorship and had high hopes for what we could do once we were free. After Marcos fell, the press was free, but the reporting remained shallow and superficial, focused mainly on what happened the day before. My colleagues and I set up the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism in 1989 because there was no room for deep digging and accountability reporting in the newspapers we had worked in. I had walked out of three newspapers in three years. It was obvious that we needed to get out of the existing newsrooms and create a structure for doing investigative reporting.

What are the key elements that make an investigative story truly “click”? What do they have to have and what should they not be missing?

Revelatory information that matters to citizens. Compelling storytelling. A narrative that is understandable to ordinary folk. Stories that generate outrage.

You’re now the director of the Stabile Center for Investigative Reporting at Columbia Journalism School. What are your main goals for the Stabile Center and its role in investigative journalism?

The Stabile Center is a teaching center. Its main goal is to train the next generation of investigative journalists. At Columbia, we teach by doing, and we encourage our students to produce ambitious investigative work while they are at school, providing them the editorial and financial resources that they need to so. We want to seed newsrooms with talented and passionate young journalists who would keep the traditions of investigative reporting alive, while also bringing with them the skills they need to succeed in the digital era. We also want to have a voice in the future of investigative reporting.

What are the essential tools that you want to give your students to enable them to succeed as investigative reporters?

The key digging skills: interviewing, finding and analyzing public records, data crunching. But we also want them to have a sense of the journalistic mission that propels the best investigative work. We want them to have an appreciation of the investigative tradition so they can learn from the past as they move forward. We are also living in an increasingly globalized world, and so we want them to think of stories not just as local or national, but also global, in scope. We want them to be skilled, nimble and also responsible, able to navigate the ethical minefields that abound in this new journalism landscape.

What is the biggest threat to investigative reporting today? What can be done to address it?

It depends on where you are. In some countries, the primary threat is safety and security. In others, it’s the lack of business models to support quality investigations. There’s also electronic surveillance and its impact on newsgathering. There are overzealous courts all over the world that continue to try journalists for all sorts reasons – revealing state secrets, invasion of privacy, defamation, etc. There’s a great deal of state insecurity, especially on national security, and that has had a chilling effect on some sectors of the profession. And perhaps the biggest challenge of all is how we make our voices heard amid the noise. There is so much that’s out there. How can watchdog reporting engage people and make more of an impact?

Ten years from today, what do you think will be the biggest differences in the field of investigative journalism?

There will be far greater use of technology in the way we gather, process and disseminate information. The platforms for news delivery will also change. Right now we are seeing people move from computers to mobile. Who knows what information delivery systems will exist in a few years?

What other tips would you give young, emerging, investigative reporters?

Young reporters are in the midst of a technological and news revolution. It’s an exciting time. The future belongs to them and they will have a chance to shape it. The challenge is to how to keep the investigative ethos alive amid the digital noise (I believe that’s a mixed metaphor). So my advice is to keep digging. Tell compelling stories that matter to people. It’s not going to be easy but keep going.