The British government’s top financial official announced Britain would slash its corporate tax to one of the lowest rates of any major economy in a bid to avoid what he called a “DIY recession” after the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union.

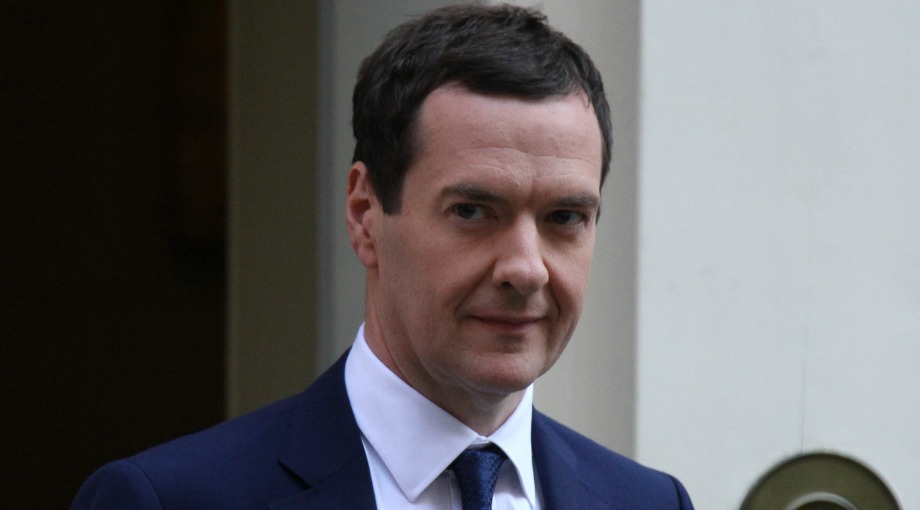

Chancellor George Osborne said the tax rate would be cut from 20 percent to less than 15 percent by 2020 in an attempt to attract continued international investment after the British exit from the EU, feeding the reported fears of Eurozone finance ministers and finance experts that Brexit could prompt a “race to the bottom” on tax policy.

According to Reuters, the OECD’s head of tax, Pascal Saint-Amans, warned in a memo written around the time of the Brexit vote that “the negative impact of the Brexit on UK competitiveness may push the UK to be even more aggressive in its tax offer” and that “a further step in that direction would really turn the UK into a tax haven type of economy.”

But the memo said such a move would be unlikely because of the unpopularity of tax giveaways to large multinationals and the heavy political price that could come with a lowering of corporate tax rates.

Even before the vote, Britain was in the process of lowering the corporate tax rate from 20 percent to 17 percent to make itself a more attractive destination for multinational corporate headquarters. The still lower rate announced by Osborne is a sure sign that the UK’s exit from the EU will redouble its resolve to maintain London’s status as Europe’s premier financial center.

“The UK had been fairly aggressive in going after US companies like Starbucks and Google over their tax bills, I think they will be much more friendly to them now,” said Gary Hufbauer, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Experts have long suspected that a British exit could lead to the adoption of tax haven-like policies beyond lower corporate tax rates, particularly in the financial services industry, as the government goes into economic damage control

Adam Posen, the director of the Peterson Institute, had warned that the UK’s departure from the EU would tempt the British government to adopt similar financial regulatory regimes as its famously opaque overseas territories.

In a Financial Times column written before the vote, Posen said that deregulating Britain’s financial services industry would be the “the most obvious parachute” to a post-”Brexit” economic slowdown. “The people in power after a Leave vote would want to be seen to shore up the City and the economy in the face of the recession they had caused,” Posen concluded, “especially given an ideology that says deregulation is the avenue to prosperity.”

Although they are not subject to EU law, offshore jurisdictions like Jersey, the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands and the Isle of Man are all overseas British territories and were repeatedly used by Mossack Fonseca, the law firm of Panama Papers fame, to shield the assets and identities of their clients.

But the UK and its overseas territories have adopted the OECD’s new Common Reporting Standard (CRS), which makes disclosure of tax residency information compulsory starting in 2016. Writing in the July issue of Taxes, a specialist publication, Brian D. Burton, an American attorney who has advised high-profile corporate clients in their dealings with the IRS, called 2016 “a landmark year for anti-tax avoidance and financial transparency initiatives,” citing the Panama Papers as an important source of information and political impetus for these efforts.

According to Hufbauer, it’s still clear which direction Britain is heading: “They won’t become more transparent. I don’t think they’ll do anything to make their system more opaque than it already is, but it’s definitely not going to go the other way either.”

However, Nicolas Veron, a Senior Fellow at Bruegel, the Brussels-based economics think-tank, who is also a visiting fellow at Peterson, pointed out that any regulatory changes would not happen overnight, since the decoupling of current financial regulations from EU-era norms would likely be a lengthy process. “Rather than a big bang, you’re going to have more of a gradual divergence,” he said.

Read more about the impact from ICIJ’s investigations, and find out how you can support ICIJ’s work

Find out first! Receive ICIJ’s investigations by email