UPDATE, 7 p.m. EST: After this article was published, Apple confirmed it held cash reserves of $269 billion outside of the U.S. at the end of 2017. Chief financial officer Luca Maestri said recent U.S. tax reform now gave Apple “the flexibility to deploy this capital.” Apple will explain how it plans to do this at its next quarterly update, Maestri said.

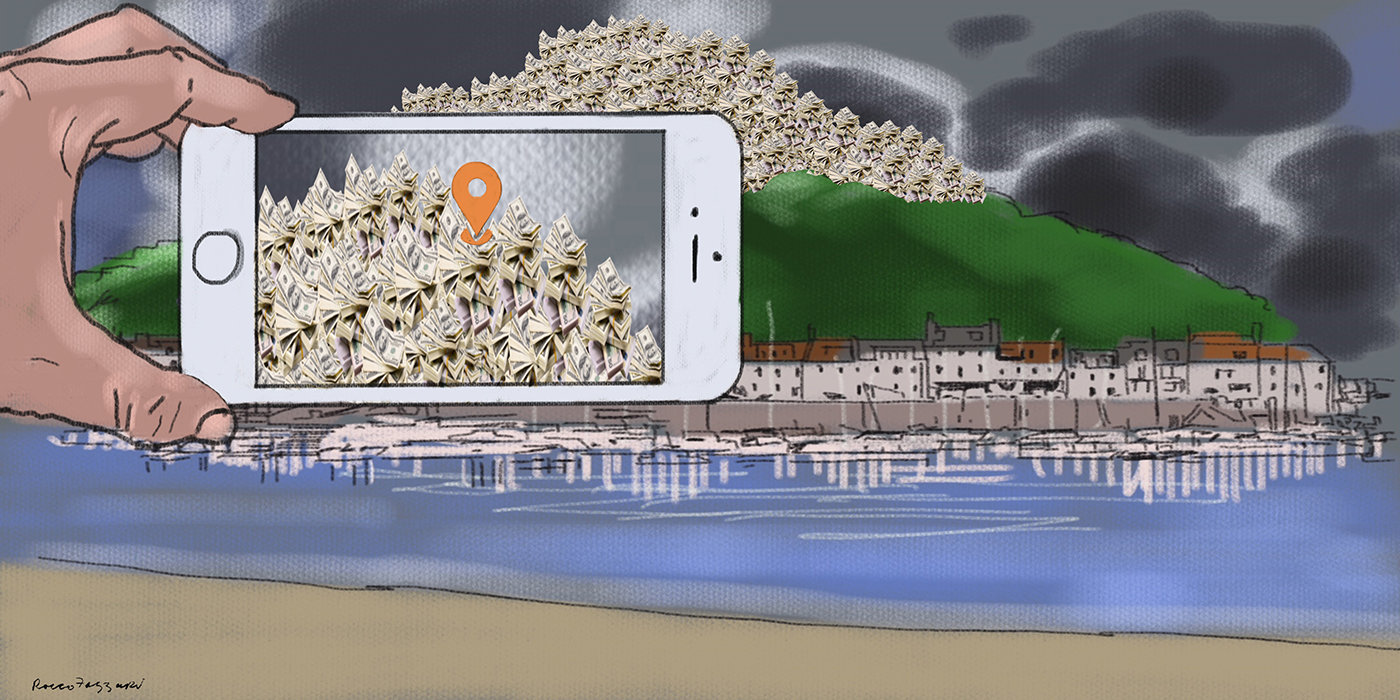

Later today, Apple chief executive Tim Cook will pick up the phone in California for a quarterly earnings call with Wall Street. As always, he is expected to provide an updated figure for the iPhone maker’s mountainous cash reserves, parked overseas as part of Apple’s highly successful tax avoidance strategy.

At last count, Apple held cash of $252.3 billion outside the United States at the end of September. That figure is now expected to have risen to between $258 billion and $261 billion, depending on how well early sales of the iPhone X have done over the busy Christmas sales period.

Two weeks ago, Apple confirmed that after many years refusing to do so, it will, finally, bring its offshore cash back to the United States following changes in tax law. How Cook plans to spend the cash is what everyone wants to know – both from today’s call and from Apple’s annual shareholder meeting in less than two week’s time.

To put this money into perspective: it is an amount close to the Gross Domestic Product of Chile and enough to buy 20 Ford-class U.S. Navy nuclear powered aircraft carriers (the Navy currently has a program for just three).

Measured against Apple itself, the company’s offshore cash is equivalent to about a third of its current market capitalization.

As ICIJ investigations have shown, this money represents years of profits that have been attributed to Irish, or stateless, Apple subsidiaries, and not California, where most product development takes place. The cash is owned by Apple Operations International, a secretive Irish subsidiary that claims tax residency in Jersey, a tax haven in the English Channel.

This contrivance – which ensures about two-thirds of Apple’s worldwide profits are recorded outside the U.S. – has for years allowed the company to avoid billions in taxes. Very little tax is been paid on these non-U.S. profits in Ireland, or elsewhere. But now, after years of U.S. tax deferrals, the earnings are returning to the United States, where they will, finally, be taxed.

The good news for Apple, though, is that a new tax law, signed by U.S. President Donald Trump in December, means returning cash will be taxed at just 15.5 percent – not the 35 percent rate Apple has for years been deferring. We have written about this retroactive tax cut before. And Professor Edward Kleinbard, a leading expert in tax law at the University of Southern California, summed it up succinctly when he told the Los Angeles Times it was a reward for “the world’s biggest tax scofflaw”.

So what now will Cook do with the tsunami of cash returning to the United States? He has talked loudly about U.S. job creation, and has teased Wall Street with idle musings on acquisition targets. But the imperatives of the stock market are simple: if a company has cash surplus to its needs, that cash must be returned to investors.

And since Apple already generates huge cash surpluses in the United States, and is already in the middle of a record-breaking $300 billion program of buybacks and dividends, it seems a fair assumption that these capital returns will be increased.

But this is politically awkward. The new tax law was sold to the U.S. electorate as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, not the “Tax Cuts and Buybacks Act”.

So, two weeks ago, Apple began a media spin campaign to stress its commitment to U.S. jobs and its participation in wider American wealth creation. In a press release, Cook promised a $350 billion “contribution” to the U.S. economy over five years, creating 20,000 jobs. Accompanying images showed blue-collar and factory floor workers.

But the numbers in Apple’s release are slippery and not especially helpful in determining how much of Apple’s repatriated cash will be spent on jobs and how much on capital returns to shareholders.

Three years ago, Gary Cohn – now Trump’s Economic Adviser and a key player in U.S. tax changes, but was then chief operating officer at Goldman Sachs – asked Cook why he was not returning offshore cash to investors. Here’s what the Financial Times reported Cook said:

At the time, activist funds led by Carl Icahn – who would later became an unpaid Trump adviser (and was also found in our Paradise Papers investigation) – and David Einhorn had bought into Apple stock and were pressing Cook for more aggressive capital returns to stockholders.

Einhorn’s and Icahn’s view was that Apple stock was undervalued because no U.S. government would ever dare to tax the billions of dollars in profits Apple had parked offshore at a rate as high as 35 percent. And together, they successfully pressured Cook to instigate an unprecedented capital return program, which has effectively continued ever since.

Now, in 2018, Apple has even more cash available for return to investors. And the prospect of large buybacks and dividends has helped the stock climb more than 50 percent since Trump won the White House with promises of tax reform.

On the campaign trail in 2016, Trump said he would get Apple to make its “damn computers and things” in the United States. (The remark was made at the end of a long speech to an audience of evangelical Christians at Liberty University, watch from the 49minutes and 19seconds mark).

As president-elect, he went further, telling the he had spoken directly to Cook about the link between tax cuts and job creation.

Trump has now chalked up Apple’s cash repatriation plans as a victory for his new tax law and for American workers.

I promised that my policies would allow companies like Apple to bring massive amounts of money back to the United States. Great to see Apple follow through as a result of TAX CUTS. Huge win for American workers and the USA! https://t.co/OwXVUyLOb1

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 17, 2018

But history tells us past repatriation tax breaks that were designed to create U.S. jobs have failed. A paper called “Watch what I do, not what I say” is a careful analysis of the impact of Homeland Investment Act 2004 on jobs.

A repeat study would be helpful. No need to change the title, though.