The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists has hundreds of members across the world. Typically, these journalists are the best in their country and have won many national and global awards. Our monthly series, Meet the Investigators, highlights the work of these tireless journalists.

This month, we speak with Yongjin Kim, editor-in-chief and chief executive of the Korea Center for Investigative Journalism. KCIJ is a Seoul-based nonprofit investigative reporting organization and runs Newstapa, a news website that presents watchdog journalism in multimedia form.

What’s the current status of investigative journalism in South Korea?

The public trust in the press in South Korea is plummeting every year. According to a recent study, only four in 10 members of the public in the country trusts the media. But investigative journalism has continued to serve as a watchdog.

We’ve had three presidents in the last 10 years. The two predecessors to the current president, Park Geun-hye and Lee Myung-bak, have both been arrested for bribery and corruption charges and are in the middle of respective trials. And investigative journalists played a role in uncovering their wrongdoing.

In 2016, KCIJ-Newstapa and many other outlets revealed that then-President Park had raked in money from corporations to set up foundations, and that behind the scheme was her old confidante, Choi Soonsil. This led to a national uproar against the administration and the famous weeks-long candlelight vigils by the people. And for the first time in Korean history, a sitting president was impeached.

With President Lee, relentless investigative reporting by KCIJ-Newstapa and other outlets led to his indictment.

What are the issues that you’re most passionate about and eager to cover? Why?

Acting as a watchdog against those in power, their wrongdoings and their abuse of power is my passion and KCIJ’s mission. Every single action and decision high ranking politicians, government officials, justices and corporate executives make just has so much influence in our society and our personal lives. Covering increasingly unfair social structures and the widening income gap in society is another passion of mine. KCIJ is currently working on a long-term project called, Who rules this country?

Looking back at your career, what’s the investigation you’re most proud of or that you had the most fun doing?

In 1990, when I was a junior reporter at KBS [Korean Broadcasting System], I investigated and exposed how the notorious Korean intelligence agency KCIA, police intelligence and the Labor Department had compiled a blacklist of students, workers and activists to oppress labor union movements and anti-government protests. I obtained a disc that contained detailed private information of more than 10,000 civilians that the government intelligence and others had collected through illegal surveillance and tailing. This blacklist was often used by the government and big corporations to block certain people from getting hired. As a result, a lot of people were unable to get corporate and public jobs or were fired because they were on the list.

Then human rights attorney Roh Moo-hyun, who became president in 2003, was on the blacklist as well. This was during the time when the South Korean government was under the de-facto military regime of Ro Taewoo who took over the office after his close friend, dictator Chun Doo-hwan.

Needless to say, it was extremely difficult to expose something like this at that time. Editors at KBS tried to block this investigative piece from running, but my colleagues and I fought really hard and the project eventually saw the light. As soon as it got out, it became a huge deal, ending up on the front page of many newspapers. I had the honor of winning the biggest journalistic award in South Korea for this story.

But more importantly, a few years later, as South Korea moved towards democracy, the government made efforts to compensate those wronged and harmed by decades of military dictatorship. And people on this blacklist were able to get the compensation they deserved. Some of those who hadn’t been able to become teachers because of the blacklist were finally able to get the job years later because the list was presented as evidence of discrimination against them.

More than anything, I was proud and happy to see those who had been wronged clear their names and get at least somewhat compensated for their suffering.

What are the challenges in reporting on North Korea and cross-border issues related to the authoritarian regime?

I have covered issues involving separated families in North and South Koreas. I also closely followed the ill-fated life of North Korean political prisoner Ri Inmo, who spent decades in prison in South Korea before his eventual return to the north. He was arrested in South Korea while working as a guerrilla activist during the Korean War and was imprisoned for 34 years for refusing to give up socialism and convert to capitalism. His wife and kids were still in North Korea.

More than one-fifth of the entire Korean peninsula’s population died, was injured, or went missing during the Korean War.

This is an on-going tragedy. Hundreds of thousands of people in the Korean peninsula are still separated from their loved ones by the border. We really can’t talk about the two Koreas without going back to the Division and the Korean War. The North Korean nuclear weapons and human rights issues are just one side of a very complicated matter that has built over decades in the peninsula.

I believe foreign media outlets, as well as Korean media outlets, should pursue peace-oriented journalism from communications and humanitarian perspectives rather than focusing on rivalry and conflicts.

You started your career working for KBS, Korea’s public broadcaster. What led you to leave your job in mainstream media and set up Newstapa?

Lee Myung-bak became president in 2008 when I was running the investigative unit at KBS. We started the vetting process of the Lee administration’s top officials and cabinet members and reported numerous cases of cabinet nominees’ improper business dealings and corruption. Two cabinet nominees even resigned immediately after our reporting.

But the Lee administration replaced then KBS CEO with a friendlier face and the new leadership disbanded the investigative unit. After that, it was basically impossible to do any investigative journalism at KBS. And things were looking pretty much the same with other networks as well. It was a time of darkness for press freedom in Korea.

In early 2013, after experiment with independent journalism, I finally quit KBS and launched with colleagues a journalism nonprofit designed to be independent from political and corporate influence. Luckily, it seems to have been the right decision.

What was the impact of Panama Papers and other offshore finance investigations you did in South Korea?

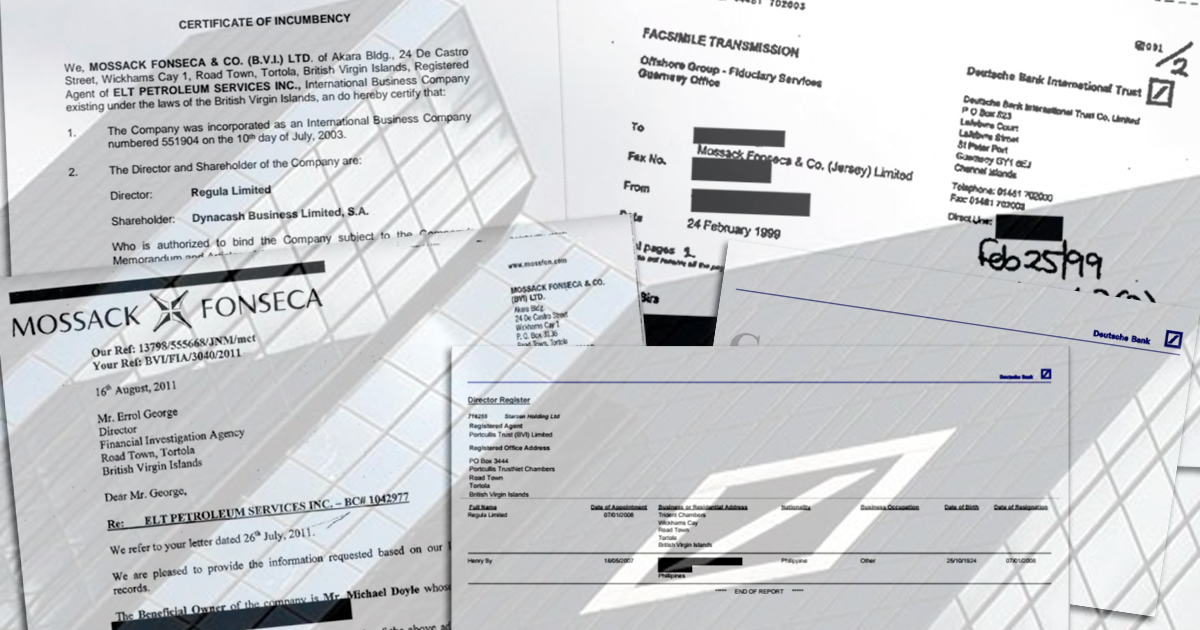

KCIJ started publishing our reports on the Offshore Leaks project in collaboration with ICIJ around May 2013. And five months later, the Korea Customs Service announced that it has identified 48 individuals who used shell companies to hide money overseas and a total of about 740 billion Korean won (about $626 million) used in illegal foreign money dealings based on KCIJ’s stories. The National Tax Service (NTS) also uncovered 11 individuals that evaded taxes using offshore shell companies and recovered 70 billion won (about $60 million) in tax evasion based on our offshore reports.

NTS said that it recovered considerable amounts of tax in evasion after KCIJ’s Panama Papers and Paradise Papers stories. However, NTS declines to disclose how much tax they have charged which companies and individuals, stating the need to protect taxpayers’ personal information. The South Korean tax agency has long been notorious for not being transparent and they rarely disclose any information on taxes for privacy reasons.

I remember walking into your Seoul office in 2016 and seeing photos of donors, many of them regular citizens. What’s the secret of KCIJ’s success?

There wasn’t any magic spell that brought in all these donating members. We just cover important issues and stories that mainstream media outlets overlook and people appreciate and support our work.

In the past six years of running KCIJ, I found that people are happy to chip in for good investigative journalism. In that sense, quality investigative journalism is the most important factor in KCIJ’s growth.

We also invite our members to various preview events and gatherings, send them periodic newsletters, and make calendars featuring our donating members’ stories. About three years ago, we also started producing documentary films based on our investigative work, and we’ve been inviting our members to premieres.

Can you tell us more about this foray into the documentary world?

We decided to experiment with documentary film using our reporting on the Korean National Intelligence Service’s fabrication of evidence in a North Korean spy scandal, something we had worked on for nearly three years. Our first film, Spy Nation, won the best documentary film award at the Jeonju International Film Festival in 2016. It also set a record as the biggest documentary box office hit in the current affairs category in South Korea, with 140,000 viewers in theaters.

The following year, we produced another documentary called the Criminal Conspiracy, a sort of a black comedy that tells the story of dysfunctional media landscape in South Korea during the Lee Myungbak and Park Geun-hye administrations. Spy Nation and the Criminal Conspiracy brought in about $300,000 and $600,000 respectively, and we used this revenue to produce more films. We just recently wrapped up our third documentary, My name is Kim Bok-dong, which will be released in August this year. It’s about the life of Kim Bok-dong, who led a painful life as a survivor of Japanese military sex slavery during World War II.

Documentary filmmaking is a very feasible side project for video-based media outlets, especially investigative journalism outlets that delve into in-depth long term issues. It’s a good example of efficient multiple use of our reporting materials. It’s also a great alternative source of revenue.

Newstapa is a multimedia outlet with over 300,000 subscribers to its Youtube channel. What’s the power of video when doing investigative journalism?

Videos deliver unmovable evidence and testimony to our audience. Moving pictures from the field and exciting ambush interviews combined with recorded evidence to support our reporting really move people. Youtube’s influence in the flow of news and information in South Korea is growing fast, and legacy media outlets are also aggressively utilizing YouTube as one of its platforms.

Do you have tips for journalists who want to produce compelling investigative videos or documentaries?

Legendary American investigative journalists Donald Barlett and James Steele emphasized the “document state of mind.” [This is the assumption that there is always a document or database related to any topic a reporter is covering.] In addition to this, I’d also like to stress the importance of “video state of mind.” There’s an old saying in the East Asian culture that “seeing something once is better than hearing it 100 times.”

Surveillance cameras in alleyways, dash cameras on cars on the streets, police and fire fighters’ body-worn cameras, and even satellite images, all these things can be powerful tools for investigative journalism.

Two years ago, to research the cause of the tragic sinking of the Sewol ferry that killed hundreds of people in 2014, we produced a documentary using dash cams inside the cars that were on the ship. Those videos recorded in the dash cams showed the public what it was really like inside the sinking ship.

The documentary has more than 2 million views on Youtube. And the investigation won the best broadcasting journalism award of the year. No great words would have showed what was happening there as well as those videos.