Late last month, the U.S. Department of Justice announced a landmark settlement with banking giant Goldman Sachs over its participation in a massive bribery scheme that syphoned hundreds of millions from Malaysian public coffers. As a part of a deal with prosecutors, the Wall Street firm agreed to pay nearly $3 billion to authorities in multiple countries, and agreed to have its Malaysian subsidiary plead guilty in a Brooklyn court to conspiring to violate U.S. bribery laws.

The fine, the largest ever under the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act followed the indictment of two Goldman executives who U.S. authorities alleged pushed the bribery ring.

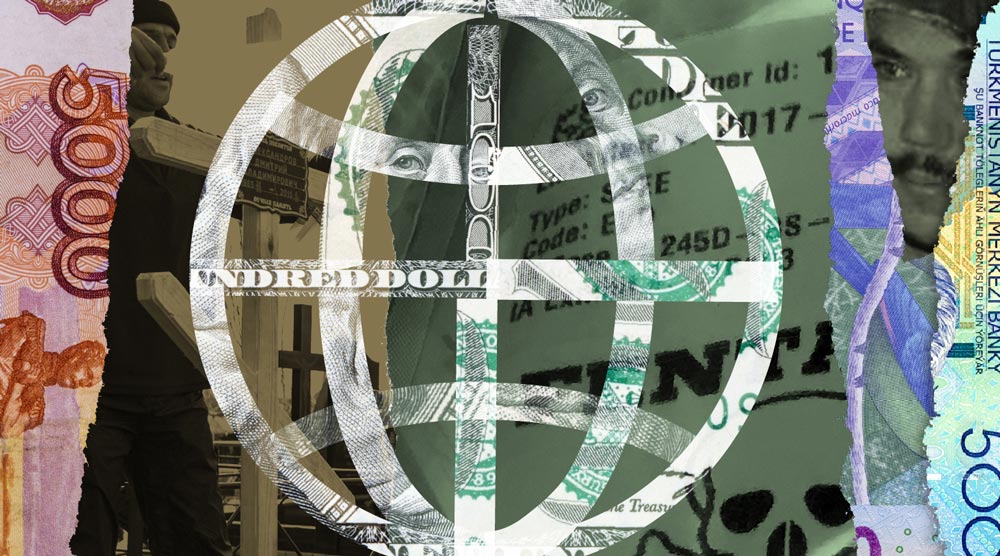

The scandal focused on a multi-billion dollar fund known as 1MDB, which was ostensibly devoted to developing the Malaysian economy. Instead, billions were illicitly syphoned from the fund, often via offshore accounts, to wealthy elites, politicians and Goldman bankers. Some of the looted money is suspected to have financed the film production of “Wolf of Wall Street,” the Hollywood feature starring Leonardo DiCaprio.

In its action against Goldman, U.S. authorities used a controversial tool called a deferred prosecution agreement, or DPA, in which an offending firm pays a fine and agrees to a period of probation in order to avoid the potentially ruinous prospect of being criminally prosecuted.

Critics say that the U.S. legal system’s increasing reliance on DPAs to address financial crime reflects its softness on corporate executives, who can often safely assume that they will not face jail time for white-collar misconduct.

In September, ICIJ published the FinCEN Files, a global investigation detailing trillions of tainted dollars moving through major U.S. banks. In many cases, huge amounts of suspicious money flowed through institutions that had already been subjected to DPAs for money laundering. To some critics, the findings epitomized the toothlessness of DPAs and their inability to deter corporate crime. “They’ve become in effect the cost of doing business rather than a real punishment,” Jed Rakoff, a senior federal judge in Manhattan, told ICIJ.

The DOJ got a bad name because, in a lot of cases, no one in the company was being held to account, but this shows an effort to do that.

— Paul Pelletier, former federal prosecutor

The Goldman DPA is part of a sprawling global enforcement action against the bank, and offers a mix of elements that reflect both unusually aggressive tactics by U.S. prosecutors toward a financial firm while also containing classic hallmarks of prosecutorial timidity, according to experts.

Paul Pelletier, a former federal prosecutor who has been a vocal critic of the heavy use of DPAs, says that the government’s action against Goldman has plenty to laud, even for a critic like himself. Pelletier says he is impressed that the government actually prosecuted two Goldman bankers who were allegedly at the heart of the bank’s involvement with 1MDB. In November 2018, the Justice Department indicted Timothy Leissner, a former Goldman partner, and Roger Ng, a former Goldman managing director, for arranging bribes and laundering money in relation to their work with 1MDB. Leissner pleaded guilty and is awaiting sentencing while Ng maintains his innocence and is expected to take his case to trial next year, according to the Wall Street Journal.

“When a company does a DPA, they are acknowledging that someone in the company was acting criminally,” Pelletier said. “The DOJ got a bad name because, in a lot of cases, no one in the company was being held to account, but this shows an effort to do that.”

Yet others have questioned whether the Justice Department’s action against Goldman ultimately amounts to a meaningful punishment, given the scale of the bank’s wrongdoing.

What stands out about the DPA to Brandon Garrett, a law professor at Duke University who has extensively studied corporate prosecutions, is the size of the fine: he says it looks surprisingly small. U.S. prosecutors, according to Garrett, took a number of steps favorable to Goldman in calculating the fine, including deducting penalties the bank had paid foreign regulators from its own fine.

The Trump administration has vowed to grant corporations more of such deductions for what it calls the “piling on” of fines from multiple law enforcement agencies when a scandal engulfs a company. Such deductions are one reason for a dramatic reduction in corporate penalties in recent years, according to the New York Times.

“It looks like a big payment, but it’s actually a fairly good deal for Goldman Sachs,” Garrett said. Last month it was reported that, in the third quarter of this year alone, Goldman Sachs earned $3.6 billion in profits – more than the sum laid out in the Justice Department’s DPA.

Garrett said that the U.S. portion of the fine was “far below” the federal guidelines on what the government could have fined Goldman for the massive theft it admitted to aiding. Garrett says that federal prosecutors granted Goldman “credits” for favorable behavior during the investigation – although “it isn’t exactly clear what that credit was for.” The DPA states that Goldman had only partially cooperated with law enforcement during the investigation. At points, the bank dragged its feet on providing key information and failed to self-report FCPA breaches that it knew had occurred, according to the filing.

“Self-reporting is incredibly important,” Garrett said. “There should be an identifiable consequence for failing to self-report. Here, I don’t think there was.”