An international group of environmentalists and lawyers is pushing for a tax on manufacturers to finance the safer management and disposal of chemicals across borders.

The Center for International Environmental Law and the International Pollutants Elimination Network submitted the proposal last month to an international forum under the umbrella of the UN Environment Programme.

More than 100 governments, civil society groups and inter-governmental organizations have committed to achieving the goal of better chemical safety by 2020 under the Strategic Approach to International Management initiative, adopted almost two decades ago.

Experts from the environmental groups have proposed a 0.5% tax, or “polluter-pays fee,” on more than 30 basic chemicals which would generate about $11.5 billion annually. That’s 85 times the sum currently estimated to finance waste management and cleanup globally, according to their report.

In the Nov. 9 online briefing, IPEN senior adviser Joe DiGangi told participants that the idea behind the proposal is a lesson “we have all learned as children, which is that we should clean up our own mess.”

“The industry should pay for the true cost of its products,” which includes pollution as well as health costs associated with chemicals that are known to disrupt normal hormone production in humans, DiGangi said.

In 2018, global sales of basic chemicals ー considered the building blocks of products such as plastics, fertilizers or pesticides ー totaled $2.3 trillion, according to estimates by the American Chemistry Council.

In comparison, in 2017, the industry reported spending $14 billion for what it calls “environmental, health and safety,” which includes hazardous waste cleanup and pollution abatement.

That is not enough to pay for the monitoring, control and disposal of the chemicals, which also requires infrastructure and personnel, the environmentalists said.

The American Chemistry Council didn’t respond to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ request for comment. The International Council of Chemical Associations said it does not support mandatory industry contributions, Chemical Watch reported.

The European Chemical Industry Council didn’t comment on the specifics of the proposal but a spokeswoman said the European industry supports “global voluntary initiatives promoting the sound management of chemicals” and takes “exposure to hazardous substances” seriously.

According to the World Health Organization’s most recent estimates, 1.6 million people died in 2016 due to exposures to a number of chemicals. Still, it’s difficult to assess the real scale of the problem because many chemicals produced by companies are not known, the WHO report said.

It’s inexplicable why countries with strapped budgets are asked to pay for this.

— Nathaniel Eisen, Center for International Environmental Law

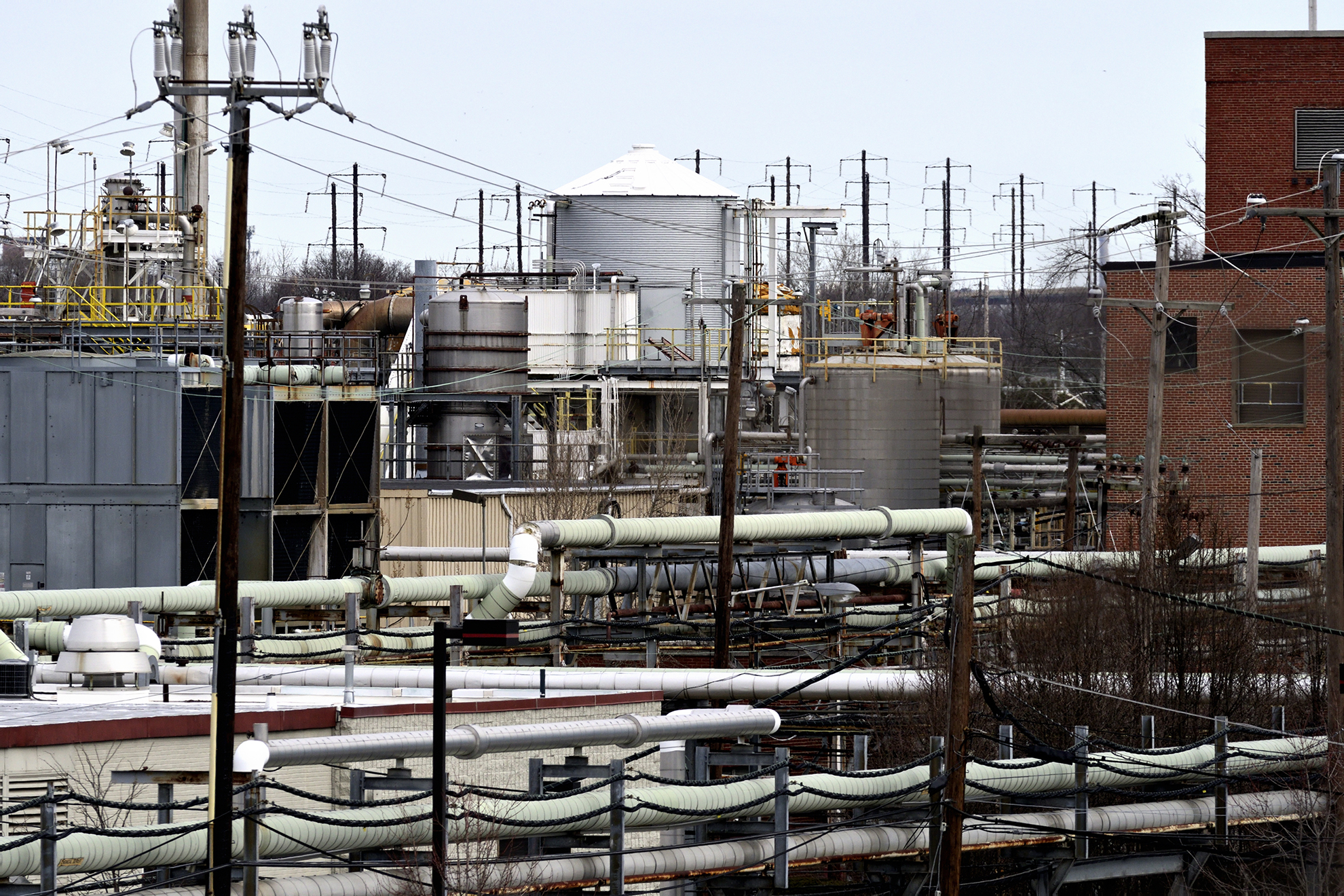

Just this month, officials in New Jersey, U.S., sued chemical giant Solvay alleging the Belgian company had released toxic compounds into water, soil, and air near its facility for years, and prevented the state from publishing data on the health effects associated with its chemicals. The state has already paid $3 million for cleanup, the state said in a 2019 directive.

A Solvay spokesperson said in an email to ICIJ that the allegations are “inaccurate, overly broad, and meritless,” and that the company is “committed” to investigating and remediating impacts caused by synthetic chemicals known as PFAS which are “scientifically attributable” to its New Jersey facility. The case is pending.

Claiming the protection of trade secrets, chemical manufacturers often use potentially polluting compounds for years before scientists and regulators learn of the dangers and are able to intervene.

Last year, a report by a German environmental charity found that major cosmetics, medicine and plastic producers, including top selling companies like BASF and INEOS, were breaking European laws by using millions of tons of chemicals without completing important safety checks. The industry’s trade organization responded to the findings saying companies are already working on the issues highlighted in the report.

A “no-brainer” for countries in need

If rich nations such as the U.S. or EU member states struggle to monitor companies and finance cleanup, the environmentalists said, the situation is worse in countries with fewer resources.

What’s more, “due to the global nature of supply chains and trade … chemical producers are often not subject to taxation or regulation in the countries where pollution control is needed,” their report says.

The new fee they proposed would be based on the volume of chemicals manufactured ー not on sales ー in order to account for transfers that may occur without recorded sales.

Governments would gather the tax in a global reserve, which would be redistributed among participating countries, prefrencing those with fewer resources which are often on the receiving end of the pollutants.

This could fund poison centers, registries of chemicals and of pollutants released into the environment, and other initiatives currently subsidized with public money, according to Nathaniel Eisen, CIEL’s legal fellow.

It’s a “no-brainer,” Eisen said. “It’s inexplicable why countries with strapped budgets are asked to pay for this.”

A statement by South Africa’s Environment Minister Barbara Creecy in June highlighted less wealthy countries’ need for “sufficient, predictable and sustainable resources” and for manufacturers’ “impactful role” in the management of chemicals they profit from.

As a continent that imports chemicals, she wrote, Africa “continues to be on the receiving end of the injustices borne from unsound management of chemicals through their life cycle and the chemical industry’s practices of putting profit before human and environment[al] health.”

Creecy, who also leads a group of African environment ministers, made the remarks in a letter to Gertrud Sahler, the president of the International Conference on Chemicals Management, which regularly reviews the proposals advanced as part of the U.N. initiative on chemicals safety.

Sahler told ICIJ that “it is clear that developing countries need significant support” and that an internationally coordinated tax such as the one proposed could provide the necessary funding.

“However, its implementation depends mainly on the willingness of producer countries and requires a new orientation in policy-making at national level. I don’t expect this to happen soon,” Sahler wrote in an email.

The groups behind the proposal have identified 10 countries as main basic chemicals producers, and potential contributors to the fund. They have also begun discussing it with some governments, they said.

Independent experts consulted by ICIJ shared enthusiasm about the proposal while acknowledging the challenges it faces, including politicians’ unwillingness to raise taxes on powerful corporations.

Despite that, such a proposal has a “huge” value because it raises awareness about the problem, according to Jacqueline Cottrell, an environmental fiscal policy consultant.

“It’s really important that … we keep thinking about how we can have a better global governance system for taxation for industry,” Cottrell said.

Past research has shown how some of the largest chemical producers such as the German giant BASF or the American company DuPont have used sophisticated tax planning strategies to avoid paying hundreds of millions of dollars in the countries where they operate.

In the U.S. alone, the industry enjoyed one of the lowest effective federal tax rates in 2018, paying a tax rate of just 4.4%, according to a report by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Representatives of NGOs and governments who adhere to the UN’s Strategic Approach initiative are scheduled to meet in July 2021 to discuss the new global chemicals framework.

Know more? Contact reporter Scilla Alecci at salecci@icij.org or contact us securely.