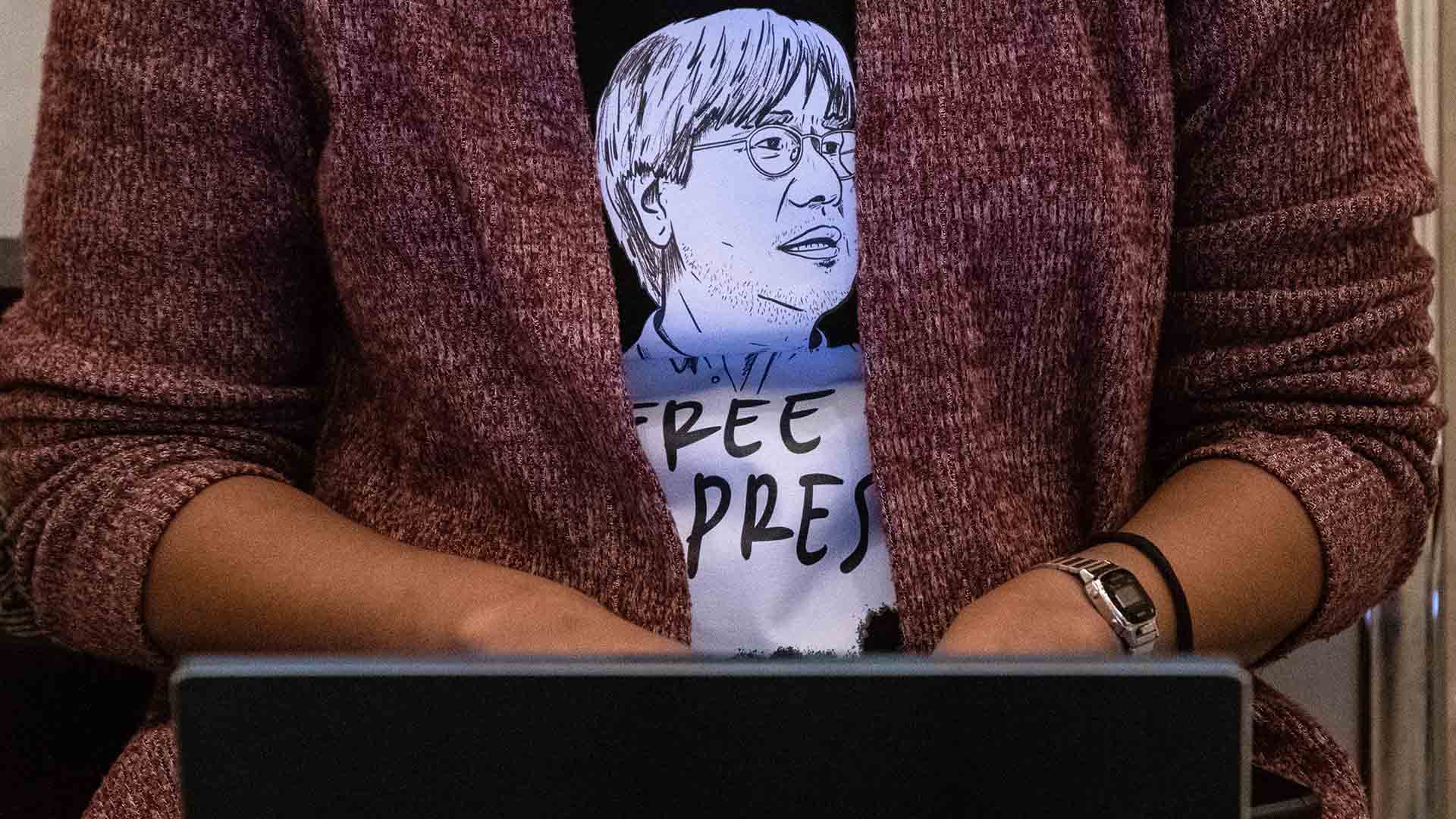

PRESS FREEDOM

Press freedom has deteriorated in the face of a global pandemic, journalists share on World Press Freedom Day

ICIJ members in every region told of rising attacks, intimidation, government pressure, restrictions, lawsuits and penalties in the past year, as well as concerns arising from changes in media ownership.

Journalism has not been spared in the global turmoil of the past 12 months, according to the latest press freedom index from Reporters Without Borders.

The report noted that, just when citizens needed accurate reporting more than ever in the face of a global pandemic, there had in fact been a “dramatic deterioration” of press freedom and access to information.

“The coronavirus pandemic has been used as grounds to block journalists’ access to information sources and reporting in the field,” RSF said in a statement. “The data shows that journalists are finding it increasingly hard to investigate and report sensitive stories, especially in Asia, the Middle East and Europe.”

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists works with hundreds of reporters from all around the world every year — and this year, many told us of increasingly challenging circumstances.

Click to jump to a region: Africa | Asia | Eastern Europe and Central Asia | Latin America | Middle East and North Africa | North America | Western Europe

Africa

By Will Fitzgibbon

Almost half of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa have “bad or very bad” situations for press freedom, according to RSF’s 2021 analysis. Even in countries with a relatively free press, journalists often work for low pay and under the constant threat of harassment.

Officials instrumentalized the COVID-19 pandemic to further suffocate freedom of the press. In Zimbabwe, reporter Hopewell Chin’ono drew international attention when officials arrested him following his investigation that helped expose alleged corruption involving coronavirus supplies.

Several countries introduced cybercrime laws that make it easy to punish journalists working online and through social media. In June, Benin reporter, Ignace Sossou, was released from prison after spending six months behind bars for – accurately – quoting the speech of a government prosecutor.

Simon Mkina, a journalist in Tanzania, told ICIJ that 2020 was “very tight and hard for independent media outlets and journalists” with incidents of “harsh repression.”

Under former President John Magufuli, who died in March after downplaying the seriousness of the pandemic, Tanzania “saw a huge fall in the sale and distribution of newspapers as people stopped buying papers that carried only ‘regime-trumpeted stories,” Mkina said.

Asia

By Scilla Alecci

In the year the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak one of the most severe pandemics of the last century, press freedom in Asia faced another crisis.

In Malaysia, a court found news site Malaysiakini guilty of contempt of court over readers’ comments deemed critical of the country’s judiciary. The court imposed a hefty $123,600 penalty on the outlet, an ICIJ partner. The decision was seen as a blow to press freedom by advocates and journalists in the region.

Filippino veteran reporter and ICIJ member Maria Ressa continues to face several lawsuits brought against her and Rappler, the news site she co-founded, by President Rodrigo Duterte’s government. Ressa, who denies any wrongdoing, said the charges are “politically motivated.”

“When journalists are attacked, our only defense is to keep shining the light,” Ressa wrote in November.

In Hong Kong, investigative journalist Bao Choy has become one of the latest victims of pro-Beijing policies that have greatly restricted press freedom over recent months. Choy was found guilty of providing false statements while researching public records in connection to an investigation into the local police.

Choy thanked her supporters in a tweet and said: “I firmly believe registry search is not a crime, journalism is not a crime, uncovering the truth is not a crime.”

In Myanmar, where a military coup in February triggered protests and a brutal crackdown by armed security forces, four newspapers have suspended publication, while five news organizations have seen their license revoked.

Citizen journalists are now using underground newsletters and clandestine radio stations to circumvent the junta-imposed censorship and internet blackout, according to the Southeast Asia Globe.

Eastern Europe and Central Asia

By Jelena Cosic

Eastern Europe and Central Asia were ranked second from the bottom in the RSF press freedom index. Last year, the region saw its most ever recorded media freedom alerts, totalling 201, which is an almost 40% increase for Council of Europe countries since 2019. There have been 52 reported cases of physical attacks and 70 cases of harassment or intimidation, according to the Council of Europe’s annual report.

In Russia last year, journalist Irina Slavina died of self-immolation. She was under a campaign of legal harassment by authorities. A controversial law was amended that allows authorities to label anyone considered to be working in the interests of a foreign state as a “foreign agent,” and be fined or even imprisoned for up to five years. Radio Free Europe was fined several times, while the country’s biggest independent media, Meduza, was named a foreign agent.

IStories editor in chief and ICIJ member Roman Anin’s apartment and office was raided by Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) on April 9. “The freedom of speech and human rights in Russia has been worsening from 2000s and every year it’s getting worse and worse. I believe that the main reason why they pressure us [independent media] is they feel that there is a demand for truth from people,” Anin told us. A statement signed by 250 reporters and media organizations released today calls on the Russian government to stop its attacks against the press.

Media in other states are under significant influence by their governments. In Poland, leading regional publisher Polska Press was purchased by a state-controlled oil company from its German owners.

Belarus is facing an alarming press freedom situation after the August 2020 presidential election and subsequent mass protests. The country faces internet cuts and leading news websites have been blocked. Journalists have been detained, beaten and imprisoned, Human Rights Watch reported. In the past year, police have sealed the office of the Belarusian Association of Journalists, raided dozens of homes and offices, and detained numerous journalists.

The court case of the murder of Slovakian investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée Martina Kušnírová saw a major setback in 2020 as a court acquitted Slovak businessman Marián Kočner and found co-defendant “Alena Z” not guilty of helping organize the murders.

In Slovenia, where journalists are directly harassed by Prime Minister Janez Jansa, the government announced that it will defund the public broadcaster RTV and also suspended financing the Slovenian Press Agency. However in April, the European Commission approved a €2.5 million (about $3 million) compensation to STA to fulfil its public service mission.

Serbian independent investigative outlet KRIK has been facing a smear campaign led by pro-government media and members of the parliament, who falsely named KRIK journalists as associates of Veljko Belivuk, a notorious leader of a criminal network.

The concentration of media ownership and influence by both private and state actors in Bulgaria is also of concern, according to RSF. Findings from a FinCEN Files investigation by ICIJ’s media partner Bivol shows that one of TV Evropa’s owners, Dobrin Ivanov, held a company that received money from an offshore entity linked to the Magnitsky scandal.

The situation is also tenuous in Central Asian countries, according to Miranda Patrucic, a regional editor at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. “Journalists in Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan were framed up with drugs, beaten and were under measures. Their relatives were pressurized, family members arrested or got fired,” Patrucic said.

Latin America

By Emilia Díaz-Struck

In the last year, more attacks and threats against journalists by some Latin American governments have emerged. High impunity rates for crimes against journalists, restrictions to access public information, attacks during the coverage of public events, intimidation, threats and anti-journalist social media campaigns — sometimes coming from governments or country leaders — have generated a hostile environment for the press from several countries in the region.

More than 20 journalists and media workers were killed in Latin America in 2020 according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Mexico remains one of the deadliest countries for journalists in the world.

In Nicaragua, authorities have been clamping down on press freedom and civil liberties since widespread anti-government protests in 2018. In February this year, two years after Nicargua’s police force illegally stormed and seized the newsrooms of Confidencial and 100% Noticias, the properties were officially confiscated and repurposed by the Ministry of Health. In El Salvador, El Faro and other media outlets have also been the focus of attacks, some of them coming directly from the president of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele.

Journalists have also faced government intimidation and discrediting campaigns in Brazil, Guatemala and Venezuela. The Brazilian National Federation of Journalists registered 428 attacks on journalists and the press in the country, with President Jair Bolsonaro linked to more than 40% of these cases.

Defamation suits have also been used in an attempt to censor journalists in several countries, including Argentina, Venezuela and Panama. In July 2020, the assets of La Prensa, Panama’s leading newspaper, were seized as part of a legal dispute initiated by former president Ernesto Pérez Balladares in 2012. Its assets remain frozen and the case continues. There is no conviction against La Prensa tied to this case.

At least 594 journalists from Latin America have died from COVID-19, according to the Press Emblem campaign, with journalists in Brazil, Peru and Mexico being worst hit.

Middle East and North Africa

By Will Fitzgibbon

“The region continues to be one of the most dangerous for journalists,” Reporters without Borders wrote in their 2021 world press freedom index. Journalists and bloggers in Algeria, Morocco, Syria, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Iran remain behind bars, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Even countries like Lebanon, with a history of vibrant and relatively free media, found itself on the slide in 2020 as reporters faced increasing attacks from police, RSF found. Nearby Jordan briefly jailed two reporters who filmed citizens’ complaints about COVID-19 restrictions.

Musab Al Shawabkeh, a Jordanian investigative journalist and editorial producer at AlJazeera Network said that “Jordanian authorities took advantage of COVID-19 pandemic, and activated a state of emergency, which restricted press work and allowed officials to arrest journalists for publishing their stories and to issue decisions banning publications.”

Al Shawabkeh said that Jordan has more than 45 laws limiting freedom of the press. “There are a lot of red lines that press in Jordan can’t cross writing about, such as the king, armed forces, religion, sex, and foreign relations, especially those with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.”

North America

By Ben Hallman

The United States saw waves of protest sweep the country over the course of 2020 and 2021, and many instances of journalists being swept up in aggressive responses by law enforcement officers with no apparent qualms about physically intimidating or detaining members of the press.

On the evening of April 11, 2021, a crowd gathered in front of police headquarters in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota, to protest the killing of Daunte Wright, a Black man fatally shot by a white police officer. Carolyn Sung, an Asian-American CNN producer, was attempting to comply with a police order to disperse when, according to a letter to Minnesota’s governor from her lawyer, she was grabbed by her backpack, thrown to the ground and her hands were zip-tied behind her back.

“Do you speak English?” one trooper yelled at Sung, even though she had identified herself — in English — as a member of the press, the letter said. She was transported to the county jail, searched, fingerprinted and ordered to strip and don an orange jumpsuit.

Since 2017, 189 journalists have been arrested while covering protests, according to the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker, which documents such incidents. Protests against police violence have proved especially perilous, with reporters not only facing arrest, but also physical harm. Over the same period of time, nearly 500 journalists have been attacked while covering protests — a disturbing figure that includes injuries suffered from rubber bullets or bean bag rounds fired by police.

It’s not just law enforcement that poses a threat: on Jan. 6, New York Times reporter Ericn Schaff said she was assaulted by rioters as they stormed the Capitol in Washington, D.C. One of her cameras was stolen and the lens of another was broken. Videos of rioters charging the media and destroying camera equipment were widely shared.

By many other measures, including an explicit Constitutional amendment, journalists in the United States enjoy a great measure of freedom to report stories without fear of government reprisal. Even so, the country ranked a middling 44th in an annual press freedom index compiled by the nonprofit Reporters Without Borders. Despite “healthy improvements” following the inauguration of President Joe Biden, the health of the press in the U.S. is threatened by “chronic, underlying conditions,” including the disappearance of local news and the “ongoing and widespread distrust” of the mainstream media, RSF says.

Western Europe

By Scilla Alecci

Before leaving his post as president of the Association of European Journalists in February, Austrian journalist Otmar Lahodynsky denounced a deterioration of media freedom in Europe, despite an increased need for impartial and factual information during the COVID-19 health emergency.

In Hungary, for instance, Lahodynsky reported that almost 80% of the media now belongs to the pro-government Kesma consortium. A court recently forced independent radio station Klubrádió off the air after the regulator found it violated media laws by, for instance, playing less Hungarian music one day than required by the law, according to Human Rights Watch.

“We have made a horrible mistake in Europe underestimating the role of the media for upholding democracy,” said Věra Jourová, vice president of the European Commission for Values and Transparency, speaking at an online event in February about the need to increase security for journalists, protect them from abusive litigations, and provide legal aid and other types of support.

In March, some 100 civil society groups and press freedom organizations called for new EU-wide measures to protect journalists and whistleblowers against so-called Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation, or SLAPPs, often filed by wealthy and powerful people to censor, harass and silence critics. In one case, an Italian journalist who reported on the Mafia faced 120 lawsuits, Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights Dunja Mijatović, wrote in a report.

The anti-SLAPP initiative was launched in 2018 by a group of European lawmakers after the assassination of Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, whose family had to fight defamation lawsuits against the slain reporter even after her death. Laws to stop such vexatious lawsuits are already in place in the U.S., Canada and Australia while media advocates have accused the EU of lagging behind.