Banks and financial service providers continue to turn a blind eye and accept customers that may be at high risk for financial crime, a new study by three renowned academics finds.

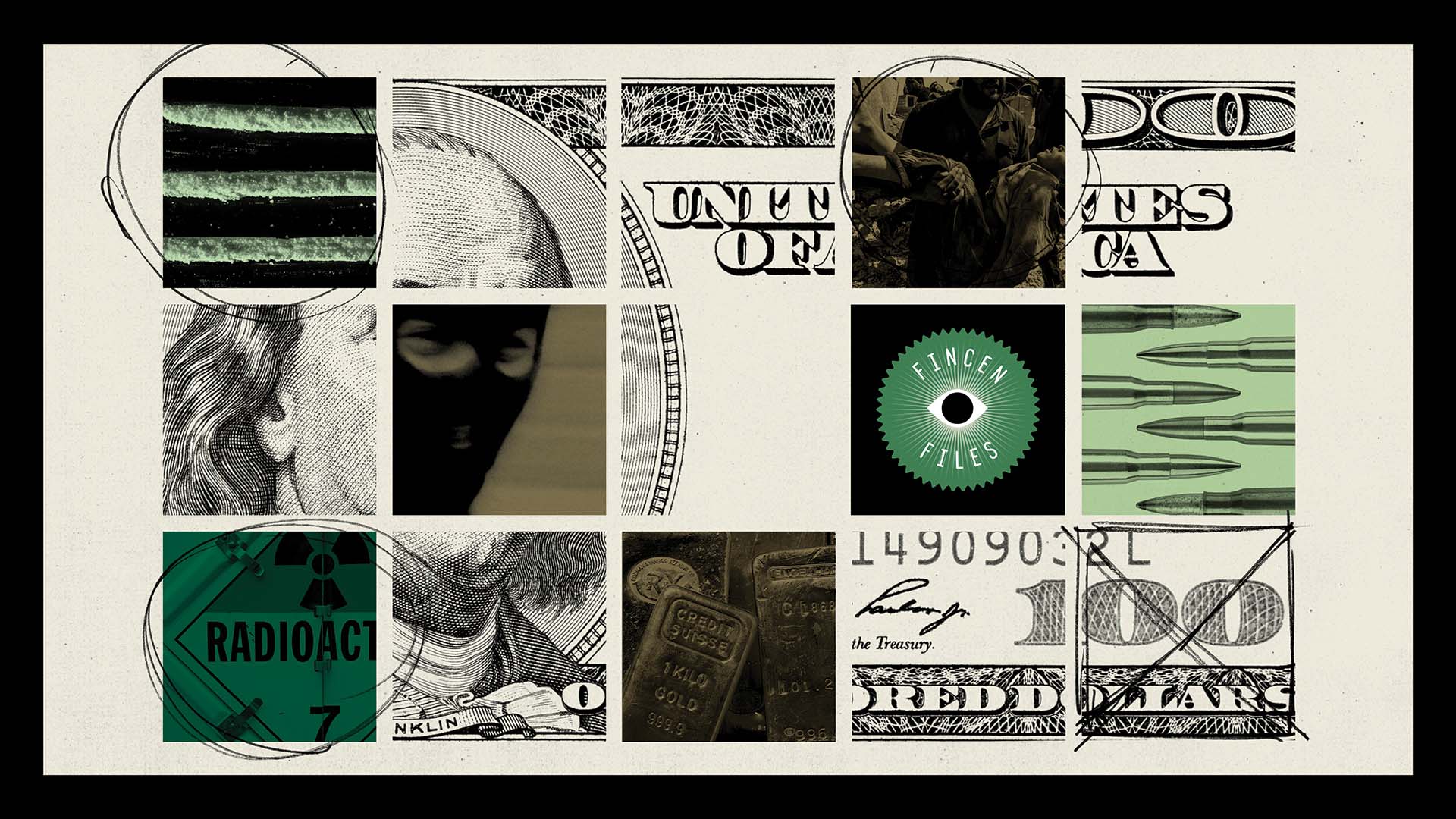

The authors are no unknowns: Michael Findley, Daniel Nielson and Jason Sharman published the 2014 book, “Global Shell Games,” which rattled the financial industry by spotlighting its poor oversight of shell companies. Two years later, ICIJ’s Panama Papers investigation did the same, followed by the Paradise Papers, the FinCEN Files and, just a few weeks ago, the Pandora Papers.

Some reforms have followed over the years. Several countries introduced registers to report true company owners, including the U.S. last year. Meanwhile, some financial institutions saw accountability for poor anti-money laundering oversight in the form of multi-billion dollar fines, and deferred-prosecution-agreements.

But despite these measures, the question remains: Do banks and financial institutions adequately monitor transactions and clients for dirty money? And if so: do their methods prevent criminal actors from getting access to the international financial system?

To search for an answer, the authors started a global experiment on regulatory compliance in the finance industry.

The researchers incorporated 12 shell companies in locations around the world and tried to open bank accounts for them. To measure if companies from stigmatized tax-haven jurisdictions would get treated differently, the scholars registered companies in the British Virgin Islands and the Seychelles. To test whether high risk of corruption changes anything, companies were set up in Papua New Guinea and Bangladesh, which are both seen to have major corruption problems according to the 2019 Corruption Perception Index. A trust and a company formed in Pakistan, which ranked highly on the 2017 Global Terrorism Index, were used to send signals of higher terrorism-financing risk.

One company was located in Delaware, a state widely seen as a tax haven, and another in California, known for higher corporate transparency standards. Some companies were formed in the U.K., a leading financial center with a growing reputation as a dirty money capital, and for placebo condition measurements, others were created in Australia and New Zealand. “We engineered radically different risk treatments by varying the jurisdiction of company incorporation and the language of the solicitation approach,” the authors explained.

The researchers then reached out to 5,000 banks and 7,000 intermediary firms that set up shell companies and work with banks to provide corporate accounts, asking all of these financial institutions to create accounts for their companies and measured their responses: Whether the banks and intermediaries replied at all, whether they were willing to offer the requested accounts or not, and whether or not they followed international rules and regulations when it came to verifying the owners behind the shell companies.

Not all banks replied. For those who did, the results are not all bad news, according to the authors: Terrorism-financing risk caused a significantly higher non-response rate as well as an increase in refusals. Besides this, the results raised many concerns:

- Originating from the known tax havens, British Virgin Islands and the Seychelles, had almost no effect on the response rate, but a decrease in the rate of compliance.

- About a third of the responses asking for additional documents and identification did not specify that these documents had to confirm the beneficial owner, the authors found. Whether intentional or not, these responses allowed verification for any representative to be sufficient.

- For for clients at high risk for secrecy and terrorism banks seem to prefer simple binary decisions of accepting or rejecting a company’s request, rather than going down the Know Your Customer road and checking backgrounds. “This is in contrast to the reaction that might be expected, whereby high-risk customers would get more scrutiny relative to low-risk customers,” the authors conclude.

- Although one would expect banks to find customers with potential for higher profits more attractive, the survey did not show such an effect. The academics set three levels of annual revenue for their companies ($500,000, $3 million and $30 million), but found banks “surprisingly insensitive to rewards.” Once again, they concluded, banks seemed to avoid KYC background checks, but rather just decided to accept or reject a new customer outright.

The researchers found that corporate services providers showed even less sensitivity to customer risks in the study.

All in all, the survey found that different risk profiles made “almost no difference” for the banks’ disposition to open up accounts to new, unknown customers. The ”risk-based“ regime is broken, the authors conclude, pointing out “that shell companies with bank accounts are perhaps the single most common mechanism for engaging in money laundering, transnational corruption, tax evasion, and other related crimes.”

The authors sounded the alarm in their report: “At a time when the world financial system is under enormous stress, and in which governments have entrusted banks with hundreds of billions of dollars of cheap or free credit, it is more important than ever to find out whether the rules that are meant to regulate banks actually work. Our study raises considerable skepticism on this score.“