MEET THE INVESTIGATORS

On a journalism journey from neighborhood news to presidential impeachment

ICIJ member Alberto Arellano started out as a kid with a typewriter before eventually becoming one of Chile’s most respected investigative reporters.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists collaborates with hundreds of members across the world. Each of these journalists is among the best in his or her country and many have won national and global awards. Our monthly series, Meet the Investigators, highlights the work of these tireless journalists.

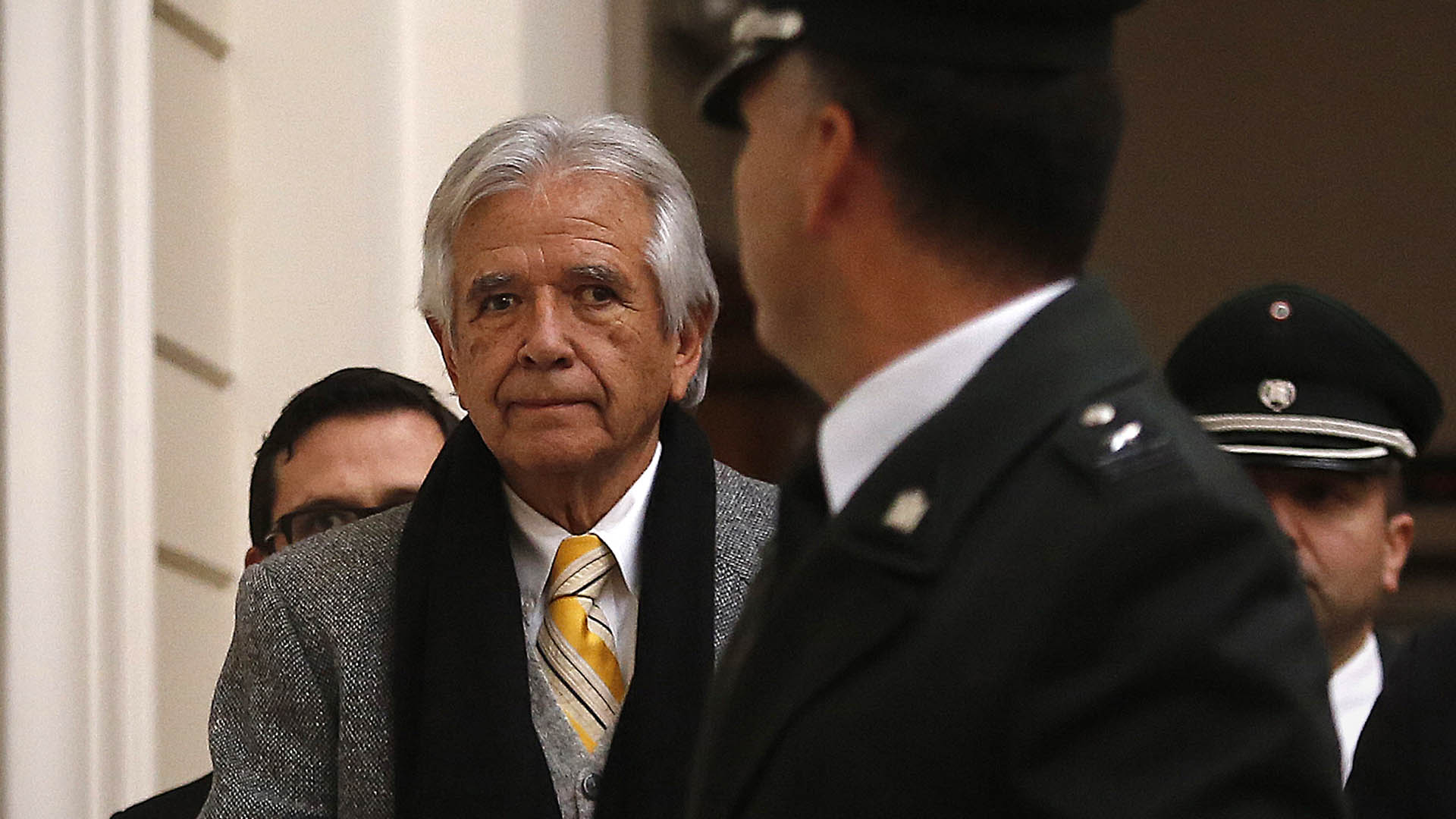

In September, we spoke with Alberto Arellano, the investigations director at Diego Portales University in Chile, about his early foray into journalism, the story that prompted the impeachment of Chile’s former president, his upcoming book and more. Arellano worked as a reporter and editor for CIPER, a center for investigative journalism in Chile, and partnered with ICIJ on the Panama, Paradise and Pandora Papers.

TRANSCRIPT

Nicole Sadek: Welcome to another episode of Meet the Investigators from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. I’m your host, Nicole Sadek, ICIJ’s editorial fellow.

For this episode, I spoke with Alberto Arellano. He’s a Chilean journalist who’s partnered with ICIJ on the Panama, Paradise and Pandora Papers, and whose work has earned him countless awards. He’s been a reporter and editor for CIPER, a center for investigative journalism in Chile, and today, is the director of investigations at Diego Portales University. And that’s not all. Last year, his work on the Pandora Papers led to Chile’s lower house impeaching the nation’s president, Sebastián Piñera.

Alberto Arellano: We just want to expose the conflict of interest of the president and his family during his first government and we never thought that this would end in an impeachment, of course.

Nicole: But before we jump into that, I want you to hear his journalist origin story, because it’s one of my favorites.

Alberto: When I was a child I created a newspaper with one of my neighbors, where we [wrote] a couple of pages, small stories about the neighborhood where we lived. We had a typewriter and we had time, so we started to write. It was in the early ’90s, and we wrote those stories, then we print, we made copies and then we sell it in a couple of pennies. It’s a little bit embarrassing for me because I don’t remember why we call it like this, but the name of the newspaper was Sorimbo.

Nicole: So you were set on journalism pretty early on. Why did you choose to get a master’s degree in history?

Alberto: I think that journalism and history are very, very complementary. Both works with facts: journalism with the present time and history, of course, with the past. I thought that the more you know the past, the more you know the present.

Nicole: That link came in handy on one of Alberto’s projects in 2014. “El millonario negocio del agua,” which translates to “The millionaire water business,” was an investigation into a businessman who exploited an old law to make a fortune out of water.

Alberto: We had to go back in the ’80s to understand how the water market in Chile works. In Chile, there is a water market, and it’s not very transparent. For this story, we didn’t receive any lead, so we started to investigate from big databases, public databases, in order to find who were the owners of the water rights in Chile.

Nicole: The issue of water rights in Chile is a complicated one. In 1980, while Chile was still under a dictatorship, the country instituted a new constitution that privatized water. That meant a basic human right was in the hands of a few powerful businessmen.

Alberto: In this case, the big surprise was the fact that we find that behind dozens of companies that have a lot of water rights from north to south of Chile was the same person, the same businessman. And we realized that in most cases this businessman didn’t develop any productive things with those water rights, but he kept these water rights in order to speculate with the prices. So when the scarcity of water in Chile was a fact, people like him did a big business because they originally got those water rights for free and forever from the state. So, this is the case of this businessman that made up at least $25 million selling the water rights that the states gave to him a lot of years ago.

Nicole: Did it surprise you to learn that this privatization process was still legal?

Alberto: Yeah, I think that it was the most surprising thing of the story. The problem is that we have water scarcity. So, it was a big contradiction of the system. But, I have to say that, recently, the law was changed, and now the public interest is in the first place. I think that we contribute to this subject. We put the subject in the public opinion, not only among the citizens, but also among the people that should make the laws in Chile.

Nicole: It’s hard to say any of Alberto’s stories pushed the public opinion more than his investigation last year into Chilean President Sebastián Piñera, as part of the Pandora Papers. The Pandora Papers was a global collaboration based on a trove of more than 11.9 million records from 14 offshore service providers. Those records included some shocking details about the president.

[Audio clip, Al Jazeera English] It was revealed in the Pandora Papers that Piñera’s family trust had sold a $125 million landholding in what is a biodiversity hotspot allegedly in exchange for ensuring the area would be available for mining.

Nicole: Alberto, how did this story land on your lap?

Alberto: For this story, I worked very closely with my colleague, Francisca Skoknic, who is also a member of the ICIJ and the founder of LaBot, which is a media in Chile. And at the very beginning, we found in the leak the name of President Piñera, we found his passport, we found a light bill with his name and then we found two offshore companies in BVI, British Virgin Island, related with their sons. Then we discover a big story because Francisca found a very sensitive document. The most important finding was the fact that the family of the president sold in BVI the shares they have in a geomining company to one of the best friends of Piñera. That mining project is located in a very fragile place from the environmental point of view, and the business was set in three payments. And the last payment depended on that place wasn’t recognized as a national or natural sanctuary. This decision depended on the government and the head of the government at that time was Sebastián Piñera. So this story was about a big conflict of interest.

Nicole: What was the reaction to your story?

Alberto: It was a scandal I guess for two things. First of all, the story itself, the business conducted in BVI and so forth, the conflict of interest that affected the president, but also it was a scandal because this story was in front of many, many media outlets abroad — I mean El País, Washington Post, the Guardian. Everybody saw the Chilean president involved in this scandal, so it was a big issue from the political and the communicational standpoint. Five days later, after our publication, the National Prosecution Office opened an investigation against him based on the information we published.

We just want to expose the conflict of interest of the president and his family during his first government and we never thought that this would end in an impeachment.

Nicole: Alberto and Francisca’s explosive story had some serious impact. One month after publication, the president was impeached by the lower house, though he later survived impeachment in the Senate. But it was unexpected.

Alberto: We just want to expose the conflict of interest of the president and his family during his first government and we never thought that this would end in an impeachment, of course. It was very rushed times for us. Gratefully, I received a lot of help for my domestic issues. I mean working with somebody who walked every day with my dog because I didn’t have time to take care of him. But it was a very busy week and month. We received a lot of callings from every part of the world to assist to TV shows. It is normal that after a couple of weeks the rush starts to descend, and we were able to take our normal lives back again. But I don’t remember any other period with this pressure.

Nicole: Alberto’s work on the Pandora Papers didn’t end with President Piñera’s impeachment. Just days ago, he and other ICIJ partners revealed that an offshore service provider allowed a Chilean arms dealer to hold offshore companies despite his shadowy past.

Alberto: This story involves a Chilean businessman, Carlos Cardoen, and he has a very interesting story because Carlos Cardoen became an important weapon producer who made his fortune under the Pinochet dictatorship back in 1980 as a supplier for the local military government. But soon he looked abroad and started to export to the Middle East his production of weapons. He made his name in the international weapon market, but suddenly a big issue stopped his career. The story, United States launched an investigation against him for buying zirconium which is a very sensitive metal, not to publicly mine explosive as he declared, officially declared that, but for producing cluster bombs for Iraq. Cardoen appears in this second part of the Pandora Papers linked to three to four offshore companies set in Panama.

Nicole: Among Alberto and his co-reporters’ biggest findings is that the Panamanian offshore firm kept Cardoen as a client for years after Interpol issued a warrant for his arrest. A representative from Cardoen’s umbrella company said that the Panama entities are old and were created in response to the warrant, which “made financial actions difficult.”

Alberto, how have journalistic collaborations like these affected your reporting?

Alberto: All the projects I work with ICIJ learned to me to follow the money, how to treat very [sensitive] information, how to connect dots, work with a lot of people. In Panama Papers, we were more than 350 journalists. In Pandora Papers, we were more than 650 journalists. They were very exciting projects from the team-working. It’s beautiful at some points to see that journalism today is about collaborate more than go alone.

Nicole: What story throughout your career are you most proud of?

Alberto: It’s not easy to pick one. Saying that, I can tell you that I’m finishing my first book. I will publish it in a couple of month. My first book about how the financial and political power became owner of the most popular soccer team in Chile, which is Colo-Colo. So suddenly, businessmen with a big influence in politics and stock market and so forth buy Colo-Colo. Among those businessmen was, guess who? Former President Sebastián Piñera, for example. This is not a book about soccer, of course, but it’s a book about power. I hope this is my best story so far.

Nicole: The book, which Alberto has been working on for the last four years, will appear in a collection of books at the investigative center at Diego Portales University, a program that he directs.

Alberto: We are a team here devoted to find, investigate and write good stories. And so far, this center has published more than 40 books of investigative journalism, and many digital projects on issues like human rights, water scarcity, the influence of Evangelical churches in politics, how the organized crime and narco traffick spread their tentacles in our country. Now, we’re working with eight new journalists who are writing new books for our collection. And we’re producing our first podcast. We will launch it at the end of November in six episodes, and the podcast, it’s about two gangs formed by teenagers who fight for territory to sell drugs. Also we are organizing a journalism festival with CIPER Chile for November as well.

Nicole: As if all that isn’t enough, Alberto’s also a professor.

Alberto: I teach investigative journalism and data journalism. After a decade of working in investigative journalism, I think that [sharing] the knowledge and experience with young people who’s looking to develop a career in this field is a must.

Nicole: What tips do you have for some of these young journalists?

Alberto: I would say, listen more than talk, but speak with people. I think that we lose a little bit the capacity to communicate with each other during the pandemic times. Read newspapers, of course, on a daily basis. I think that good information is not in social media. And people is more and more consuming information from social media, and journalists also. Read a lot, read and enjoy books to, of course, to learn to write, for example. I think that more you read the better you write. Ask questions that no one has asked. And be ethic always.

Nicole: That’s another episode of Meet the Investigators. Thanks to Alberto Arellano for joining me today. Make sure to tune in next month, when we’ll dive even deeper into the lasting impact of the Pandora Papers as we celebrate the project’s one-year anniversary.

Meet the Investigators is a production of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. This episode was produced and edited by me, Nicole Sadek, with help from Hamish Boland-Rudder. As always, don’t forget to share the episode on social media using the #MeetTheInvestigators. See you next month.