MEET THE INVESTIGATORS

Shining a light on corruption in Comoros

In this month’s Meet the Investigators, Hayatte Abdou shares stories from her courageous accountability reporting, defying government threats and intimidation in the island country of less than a million people

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists collaborates with hundreds of members across the world. Each of these journalists is among the best in his or her country and many have won national and global awards. Our monthly series, Meet the Investigators, highlights the work of these tireless journalists.

In this month’s Meet the Investigators, Hayatte Abdou shares stories from her courageous career as an investigative reporter in Comoros, the small island state off the coast of East Africa where she is ICIJ’s first and only member.

At its core, Hayatte’s work is about demanding accountability, despite government threats and intimidation, rampant corruption and the precarious financial state of journalism in a country of less than a million people. Hayatte is one of 20 new ICIJ members.

TRANSCRIPT:

Carmen Molina Acosta: Hello and welcome back to Meet the Investigators from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. I’m your new host, Carmen Molina Acosta, and I’m a producer here at ICIJ.

If you’re joining us for the first time, Meet the Investigators is a podcast where we sit down and hear from one ICIJ member from across the globe.

Today, we’re joined by Hayatte Abdou of the Comoros. She’s the consortium’s first Comorian member, and founder of a new outlet, the National Magazine Comores. Brenda Medina is a reporter here at ICIJ who talked with her for this episode– hi, Brenda!

Brenda Medina: Hello!

Carmen: Brenda, for those who might not know– where are the Comoros?

Brenda: The Comoros is a tiny group of islands off the shore of East Africa, and it has a population of less than a million people. The islands were once a French colony, and gained independence in 1975.

Hayatte joined us from a dark room– that gradually turned black as the sun went down. There was no power that evening.

Hayatte Abdou: I’m Hyatte Abdou, an investigative journalist from Comoros Island.

Brenda: That’s only one of the challenges to being a Comorian journalist. On the islands, there’s only a few outlets– and Hyatte told us that there is no journalism degree at the country’s national university.

Carmen: According to Reporters without Borders, journalists in the Comoros are regularly subjected to government intimidation. For example, in 2021, the incoming finance minister threatened to send “thugs” to “rip to pieces” journalists who dared criticize him.

When you live in a poor country and justice is really corrupted, and it’s very important to keep your conscience intact.

Hayatte: When you live in a poor country and justice is really corrupted, and it’s very important to keep your conscience intact.

Brenda: In her six years as a journalist, and three doing investigative work, Hayatte has reported a lot on social issues.

Hayatte: Me, I work a lot in the social causes: health and education and gender. And one day, I did a paper on malaria and the military health laboratory that’s given a false positive result.

Brenda: People working at the military health laboratory told her they suspected the malaria tests results were inaccurate. Soon after that story was published, her phone rang. She knew it wasn’t a good sign.

Hayatte: “And I just gave the phone to my director of publication and I turned to him, “boss, it’s for you.” I’m not paid– I’m not paid to be intimidated to write.

Carmen: So then what happened?

Brenda: When he hung up the phone, her boss told her she had been summoned by the Army.

Hayatte: I told to him, who is summoning me? No way. I’m not going anywhere– that is your job, not mine. And I don’t accept to summoning by Army because I do my job. I think it’s really unfair and I don’t accept.

I’m just a journalist. My job is ask a question and writing, and if the Army has a problem about that, it can just go right to the authority, but not me.

If I make a mistake, I apologize. But I can’t, I don’t accept it, intimidation. I refused.

Carmen: Wow, so working with the government is really sort of fraught, then, isn’t it?

Brenda: Yes, definitely. A lot of her work has been about government accountability. And some stories hit really close to home.

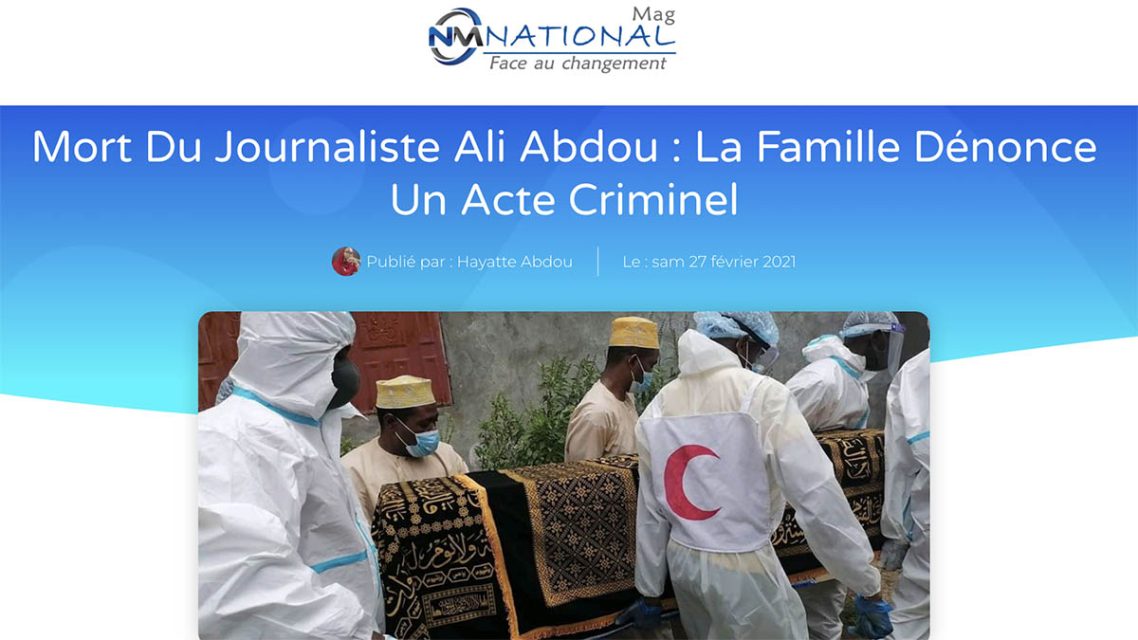

In December 2020, one of her colleagues, a journalist named Ali Abdou [no relation], was found dead in his home. He was the first president of the National Union of Journalists in the Comoros.

Hayatte: He was really kind, you know, and really funny, too, laughing every time and everybody know him.

It’s hard for me to talk about… about… about this. This story is really difficult for me.

Brenda: After a two-day investigation, the authorities concluded Ali’s death was due to natural causes. But his family disagreed.

Hayatte started unraveling the story while she was in Tunisia at a journalism event. She noticed that Ali’s Facebook messenger account was still active.

She sent a message … and was shocked to get a reply.

Hayatte: I wrote a message to the person and I, I tell her: “You know, Ali was our colleague, friend and our brother. And actually, he died. And we still in shock. Seeing this account active increases our pain.”

And she answered me: “I’m her sister, my brother is murdered and nobody wants to know why. Not even journalists.”

Brenda: Hayatte promised to hear them out. When she returned to the Comoros, she went to meet with Ali’s family.

Hayatte: The whole family was there and waiting for me. The mother, four sisters and brother-in-law. I listened to them for many hours.

Carmen: What did she find out?

Brenda: The prosecutor on the case concluded that Ali died by a natural cause …but the family said his mattress was soaked in blood, and there were signs of physical struggle. One of Ali’s cousins told Hayatte that the police officers on the scene had burnt the mattress. She spent hours listening to their testimonies.

Hayatte: I was tired. I was angry. I was exhausted.

Brenda: She told me that was the worst day of her life.

Hayatte: It’s very difficult for me but the most difficult thing was to fight, to fight against myself, because I was really angry. Really angry for me first; really angry for all the professionals, journalists; I really angry for society; I really angry for justice.

When I saw the picture for the body of Ali… it was really horrible.

Brenda: The person who showed her the photographs tried to warn Hayatte before she saw them.

Hayatte: He asked me, “Are you see a body like that before?”

And I say, “I am not.”

“Okay,” and he tell me, “sit down, I’m gonna show you right now. But just to show you.”

I say, “Okay. Show me.”

Brenda: She didn’t believe the government could lie so blatantly. At a press conference, the prosecutor had insisted no blood was found. But in the photos, Hayatte saw a halo of blood, and Ali’s left eye dangling from its socket.

Hayatte: I was really naive. I was really stupid.

Brenda: When she came home from seeing those photos, she just wanted to forget it all.

Hayatte: I needed to forget. Forget the picture. Forget this story. Forget about the conference of the Republic prosecutor, forget everything.

Carmen: What does she mean by that, that she needed to forget everything?

Brenda: Oh, that has happened to me before. When a story gets too intense you just need to step away from it, because it becomes overwhelming. And I have heard from other colleagues that this has happend to them, too, when writing about topics like rape or death.

Carmen: Wow. But then what do you do?

Brenda: Well… when you’re ready… you get back to work. And that’s what Hayatte did. She finished her reporting and published her story in February of 2021.

About two months later, the prosecutor who had lied during the press conference was fired…

Hayatte: I never asked for a police investigation. I never asked from the Republic or prosecutor, I never asked anyone. I need just to prove the prosecutor is lying.

Carmen: So why did the prosecutor lie?

Brenda: It’s complicated… and, honestly, still a little unclear. Ali’s relatives told Hayatte about a family dispute… and how the prosecutor had a potential conflict of interest.

But what her investigation did was expose that the prosecutor did lie – and she held him accountable.

Carmen: It’s obviously still very difficult for her to talk about.

Brenda: It is. But there’s another investigation she did that she was a lot more excited to talk about.

Hayatte: This one is my favorite!

Brenda: And that was her investigation into the Comorian tax authority

Hayatte: The corruption of the tax administration has never been a secret for anyone, you know, has never been a secret.

Brenda: Hayatte’s investigation exposed what was pretty much an open secret in the Comoros– that agents in the tax administration were taking advantage of their position to extort business owners. They demanded payment and threatened to close shops if the owners didn’t comply.

Hayatte: We just said it louder than everyone else… It was really incredible. You know? Every everyone says that is a good job Oh seriously finally it was really incredible it’s amazing, it’s amazing

Brenda: The president of the Comoros ended up firing the director of the tax administration.

Carmen: Really?

Brenda: Yes!

Brenda: You’re just… getting people fired in the Comoros, Hayatte. You have had two directors fired now, right? Or a director and a prosecutor, after your investigations?

Hayatte: Yeah… yeah!

Brenda: That kind of accountability journalism is part of the reason Hayatte co-founded a new media outlet, National Magazine Comores. It’s a four person publication, and it is entirely self-funded.

Carmen: Wait– they don’t get funding from anywhere?

Brenda: No, and that’s actually one of the biggest obstacles to journalism in the Comoros– financial independence. Unless you work for the state-sponsored paper, you can’t really make a living from the profession, so reporters often have more than one job.

Hayatte: It’s important for journalists to be independent and to be economic[ally] secure, but you know, in Comoros, it’s really difficult.

For me and my director, we pay to investigate, but the information on our website, it’s free, and we pay from our pockets.

Brenda: So doing journalism in the Comoros, because of all these obstacles we’ve talked about, can be a really complicated, and also sort of lonely endeavor. So when Hayatte heard she had been invited to be an ICIJ member, Carmen, she was ecstatic.

Hayatte: When I woke up, and I checked my phone for the news, and I see the invitation, I go, WOO! It’s really amazing! What?! And, you know, I think it’s the first time in Comoros and it’s really important not for me, you know, but for our society, not for our readers, but for future generations.

It’s just only amazing to belong in a professional family because I’m actually the only investigative journalist from Comoros Islands, and having a big umbrella over my head also helped me to feel confident.

Brenda: She had the biggest smile, Carmen, when talking about it– you could tell she was so excited. She talked about journalism like a patriotic duty she had to her country.

Hayatte: In Comoros, we don’t have a habit to read a story like an investigative story, you know.

I think the journalists in Comoros can break the chain, you know, and maybe one day we can do the job, because the Comorian people need a defender. That is our job.

Brenda: And sure enough, just as Hayatte was talking about the importance of bringing information to light– her electricity came back on!

Hayatte: It’s back!

Carmen: If that’s not serendipitous, I don’t know what is.

Brenda: She was so inspiring– really an impressive journalist to interview.

Carmen: Thank you so much, Brenda, for interviewing her!

Brenda: You’re welcome.

Carmen: That’s it for this month’s Meet the Investigators– again, that was Hayatte Abdou of the Comoros. She’s one of 20 new members we’ve recently added to our network of journalists across the globe. You can meet the rest at icij.org. I’m Carmen Molina Acosta, and that was our Brenda Medina. We’ll see you next month.