Maduro regime doubles down on censorship and repression in lead-up to Venezuelan election

One expert called Venezuela’s sprawling surveillance, disinformation and censorship campaigns a model for “the future of authoritarianism elsewhere in the world.”

As Venezuela heads into a critical election on July 28, a new report details how the Latin American country became a laboratory for digital repression, bolstering the current regime and accelerating democratic backsliding across the region.

After taking power in 2013, President Nicolás Maduro was swift to tamp down protests with force and persecute dissidents, including journalists. His government also built a sprawling surveillance apparatus to monitor and control speech online, according to the study by the Digital Forensic Research Lab, which studies disinformation. The report’s authors described the state surveillance apparatus as a “dragnet” that captured data from a large swathe of Venezuelans while also providing in-depth monitoring of a select group of targets.

At the same time, state-orchestrated disinformation campaigns regularly leveraged online tools — including paid troll accounts on social media and fake fringe websites — to defame and harass journalists, human rights advocates and politicians, the report found. Maduro has repeatedly denied that he is authoritarian.

If we want to see the future of authoritarianism elsewhere in the world, we need only look to Venezuela.

— Ben Roswell, former Canadian ambassador to Venezuela

“The government controls what people can access, perceive and see on the internet, even social media, where they have little to no capacity to limit people’s choices on what to follow. They just completely cover … independent perspectives and critical voices with misinformation, disinformation attacks and more,” co-author Andrés Azpúrua, who leads digital rights organization Conexión Segura y Libre, told ICIJ.

Azpúrua said Venezuela was an early adopter of generative AI dupes, such as fake English-language newscasts to sow distrust in foreign media. In February 2023, the report said, AI was used to create a series of videos touting the country’s supposed economic recovery. The Maduro government has also been accused of using information operations to interfere with other Latin American countries’ elections, influence judiciary decisions in Africa and undermine sanctions on human rights violators.

“There were experiments conducted in Venezuela, and they have been explicitly adapted elsewhere,” said Ben Roswell, a former Canadian ambassador to Venezuela, during an online launch event for the report on Monday. “If we want to see the future of authoritarianism elsewhere in the world, we need only look to Venezuela.”

Many of the tactics Maduro has relied on to stymie domestic dissent have been on display in the lead-up to the July 28 election, where he will face a resurgent opposition represented by Edmundo Gonzalez, a former diplomat. While Gonzalez’s campaign has caught the attention of some international press, coverage inside Venezuela has been largely confined to independent news websites, many of which are blocked by state and private internet providers, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Meanwhile, state-controlled TV and radio stations have been flooded with propaganda favorable to the ruling party.

“The disinformation is so rampant during the election,” said Azpúrua. “The presidential campaign officially began on July 4. Two fact-checking websites got blocked by the government that same day.” Another fact-checking website was blocked shortly afterward, he said, right as “the disinformation campaigns were ramping up.”

In a post on X underscoring the problem, Azpúrua said that shortly after the launch event four more news sites were blocked along with VE sin Filtro, a Conexión Segura y Libre site that documents internet censorship.

En la mañana estaba presentando este reporte sobre el autoritarismo digital de #Venezuela.

Minutos luego de terminar, bloquearon 4 medios de noticias más, y dos páginas de ONG incluyendo nuestro @vesinfiltro.

Seguiremos documentado y resistiendo el autoritarismo en #internetVE https://t.co/mq1ESVLfVx

— Andres Azpurua (@andresAzp) July 23, 2024

“It shows that they’re gearing up for even more censorship,” Azpúrua told ICIJ. “Regardless of the outcome of the election, Venezuelans will continue to resist digital authoritarianism for the time being and we will continue to struggle to stay connected.”

More than 100 websites had already been blocked, including those of 40-plus media outlets, when the June 22 report was compiled. The use of virtual private networks, or VPNs, and other censorship-circumvention tools were also heavily restricted. The authors noted that the fragmentation of Venezuela’s media industry happened gradually, fueled by the rise of state-controlled media and online censorship along with the 2015 collapse of the country’s economy.

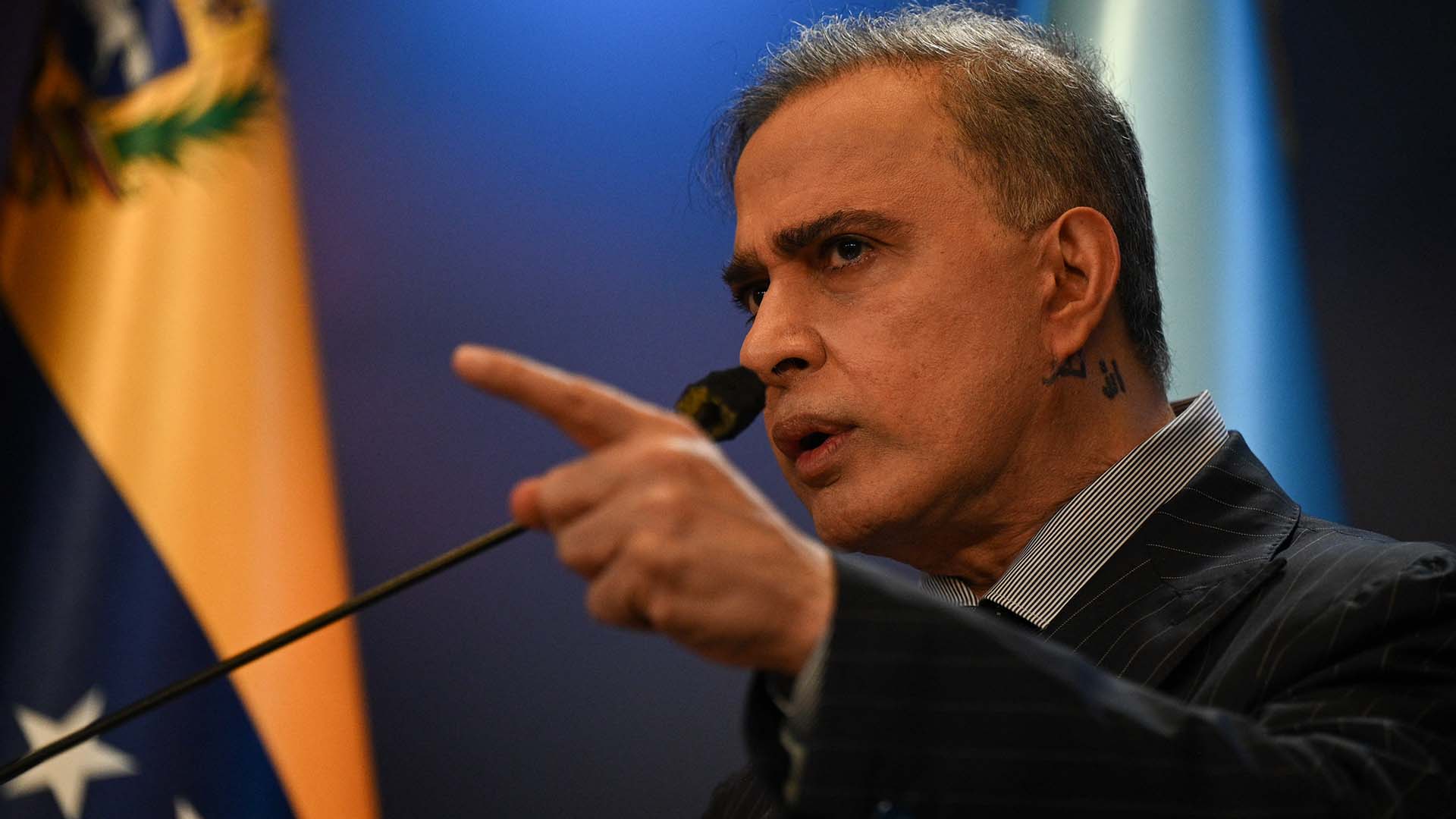

In an email to ICIJ, Joseph Poliszuk, the co-editor of ICIJ media partner Armando.info likened the shuttering of hundreds of outlets to a form of “progressive censorship.” The investigative outlet is no stranger to political attacks: Earlier this year, Venezuela’s attorney general tried to discredit its journalists’ reporting on government corruption ahead of the release of a Frontline documentary about their work.

With the latest opinion polls showing Maduro trailing Gonzalez, the Venezuelan electoral system is now under scrutiny. Reuters reported several decisions by electoral authorities — including limiting access to polling stations and the layout of the ballot — seemed intended to confuse voters. On Monday, Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, urged his Venezuelan counterpart to respect the election outcome after Maduro referenced a possible post-election “bloodbath.”

“It is difficult to make predictions about [Sunday],” Poliszuk said. “In other [election] processes, Chavismo has allowed and even applied all kinds of censorship mechanisms: from the repression of journalists to the closure of media outlets and Internet restrictions.

“In Caracas and all cities in the country there are mechanisms with a kind of random blocking, where the Internet goes down by zones and times. It is sophisticated censorship.”