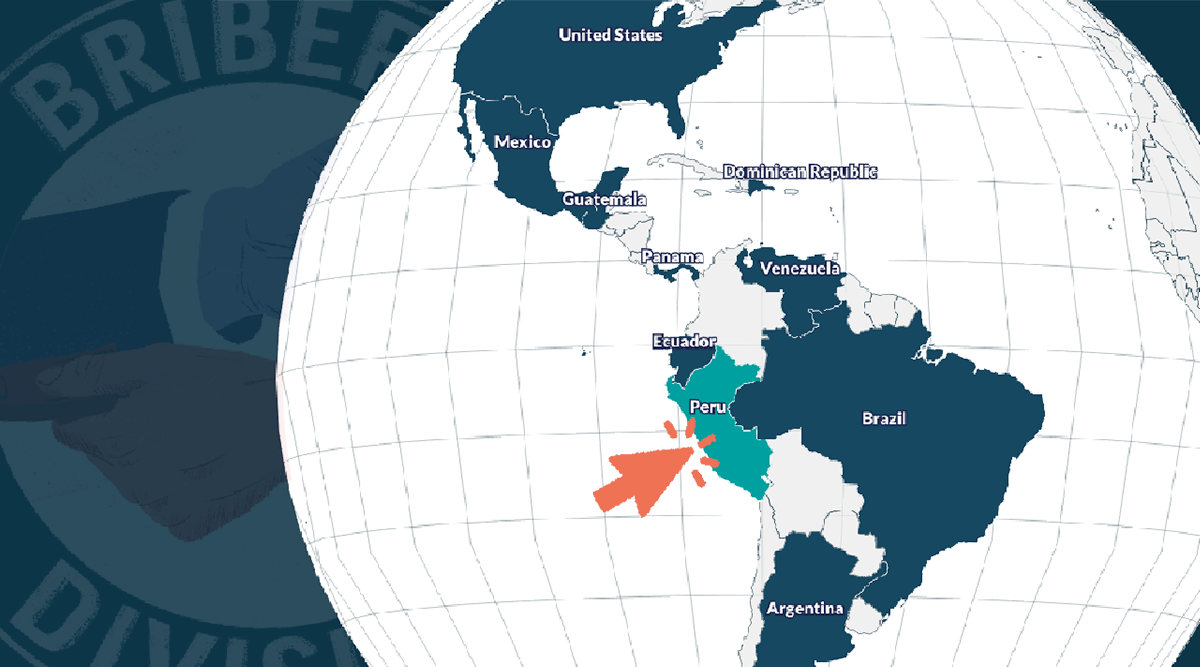

When Ecuadorian journalist Andersson Boscán shared more than 13,000 documents leaked from the disgraced multinational construction firm Odebrecht, we were excited to see what the files revealed.

As a team of staff and trusted members from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists began to sift through the materials this spring, we quickly recognized that we had both a major story and a complex challenge.

The documents came from a secret communication system employed by a division of Odebrecht that existed primarily to manage the company’s bribes. The trove was extensive and contained abundant records of secret payments that had never before been disclosed. But they were also incomplete, and sometimes offered only a partial glimpse into the transactions that had taken place.

What’s more, the documents referred to individuals only by codenames.

Over several months, the ICIJ team carefully analyzed Odebrecht’s files, deciphering enough of the materials to break significant stories connecting numerous public works projects and prominent figures to Odebrecht’s shadowy payments for the first time. (Review the hidden payments revealed by the project here.)

Here are some of the key documents that fueled the Bribery Division investigation – and how they helped ICIJ’s team to uncover the truth.

The 2014 payment spreadsheet

This document provided the backbone of our investigation. It included records of more than 600 payments made by Odebrecht’s Division of Structured Operations between December 2013 and December 2014, and included an amount, date, beneficiary company and associated public works project for each payment. It also included a codename for the recipient of each payment – often colorful and irreverent nicknames such as Bambi, Stalin, Robocop and Darth Vader.

This spreadsheet revealed undisclosed payments related to major infrastructure projects such as the Gasoducto Sur gas pipeline in Peru, the Punta Catalina coal-fired power plant in the Dominican Republic and the subway system in Panama City.

The Quito Metro email chain

The subway system in Quito, Ecuador, whose $2 billion price tag represented Odebrecht’s biggest contract in the country, was widely believed to be free of corruption after an investigation by local prosecutors found no evidence to sustain charges. But an email that we found in the leaked documents suggested otherwise.

It showed three employees of Odebrecht’s Division of Structured Operations – codenamed “Silver,” “Fred” and “Wilson” – discussed payments for the Quito Metro routed through their department. The message notes that the payment was made through the company Fortress Investors Ltd., which appears repeatedly in the Bribery Division’s files as a conduit for payments. The records don’t say who received the secret payments or their purpose.

The ‘Divide it into smaller payments’ email

Most of the secret documents were dry and technical, making it easy to forget that they reflected the inner workings a massive criminal conspiracy. But an unusual piece of advice offered in one email provided a striking reminder of the corruption at the heart of the unit’s transactions.

In the email, a representative of a company in Dubai that is handling payments made by the Division of Structured Operations advises Odebrecht to split the payments into smaller amounts in order to avoid raising suspicions from banks. “We highly recommend that we limit our transfers and divide it into smaller payments so as we could prevent any issues,” the employee writes.

The Know Your Client email

An extraordinary feat of Odebrecht’s bribery unit is that it managed to operate with impunity for nearly a decade, from 2006 through late 2014. This included dealings with outside companies, banks and law firms, which either intentionally or unwittingly, helped it to shuffle billions of dollars through a web of offshore companies based in jurisdictions across the world.

In this email, a lawyer pushes back and demands to know more details about the division’s transactions, setting off a scramble among its employees to produce contracts and other needed documents justifying its payments. (Many of the unit’s contracts were, in fact, fictitious, Odebrecht later acknowledged to prosecutors.)

“We understand that this is an important client with a lot of prospective projects however we are also facing increasing compliance requirements at our end,” the lawyer writes. “Each flow of funds/transaction needs to be documented.”