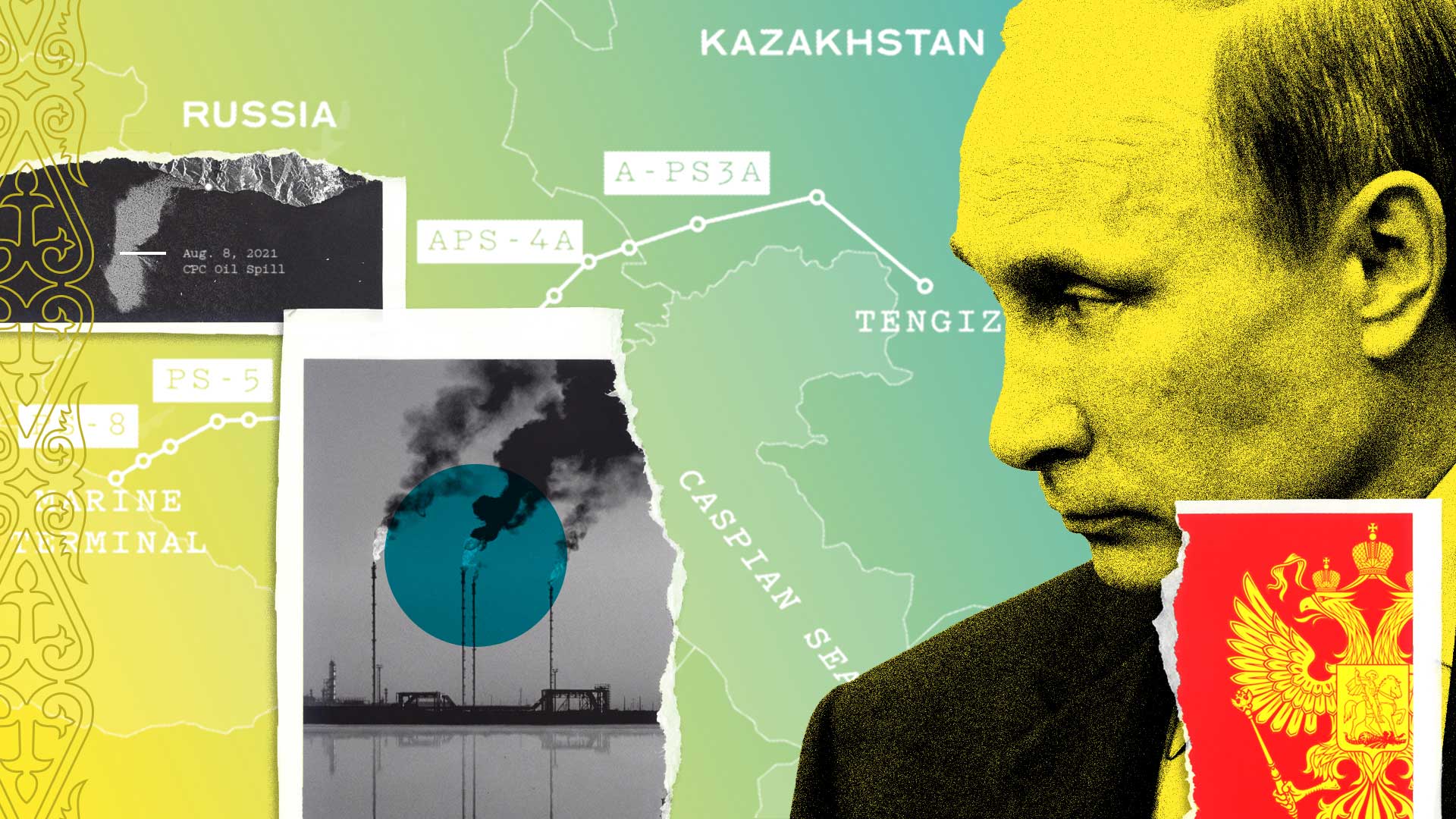

On a late August afternoon in 2021 the mooring master made a frantic call to a dispatcher at Russia’s largest port, Novorossiysk.

“Stop! Stop! Stop loading tanker Minerva Symphony!” he shouted.

But the damage had already been done. A floating platform used to load oil onto the Greek tanker had malfunctioned, unleashing a six-foot-high jet of oil into the Black Sea, three miles off the Russian coast. The oil, which had been flowing through the pipeline that was the heart of the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC), gushed for nearly a half hour before workers were able to stop it. It inched dangerously close to a popular beach dozens of miles from the so-called Putin’s Palace, an extravagant residence reportedly used by the Russian president.

A full hour passed before 306 workers, 18 ships, four oil-recovery systems and nine specialized vessels with collection tanks were deployed. The oil slicked seven miles of coastline, and by the next evening it had spread to between 20 and 32 square miles, threatening farmers, villagers, wildlife and tourists. The cleanup lasted seven days, with only about 45 tons of the spilled oil recovered out of hundreds lost, according to a Russian court ruling. And then the disaster got worse. A violent storm swept through the region with heavy rain and fierce winds, halting efforts to corral the oil, which, according to eco-activists, had settled on the bottom of the sea.

The havoc in the water, which was ultimately a result of prioritizing profits over safety, was only the latest adversity for the Western oil giants who long ago had accepted the consequences of doing business in Russia and neighboring Kazakhstan.

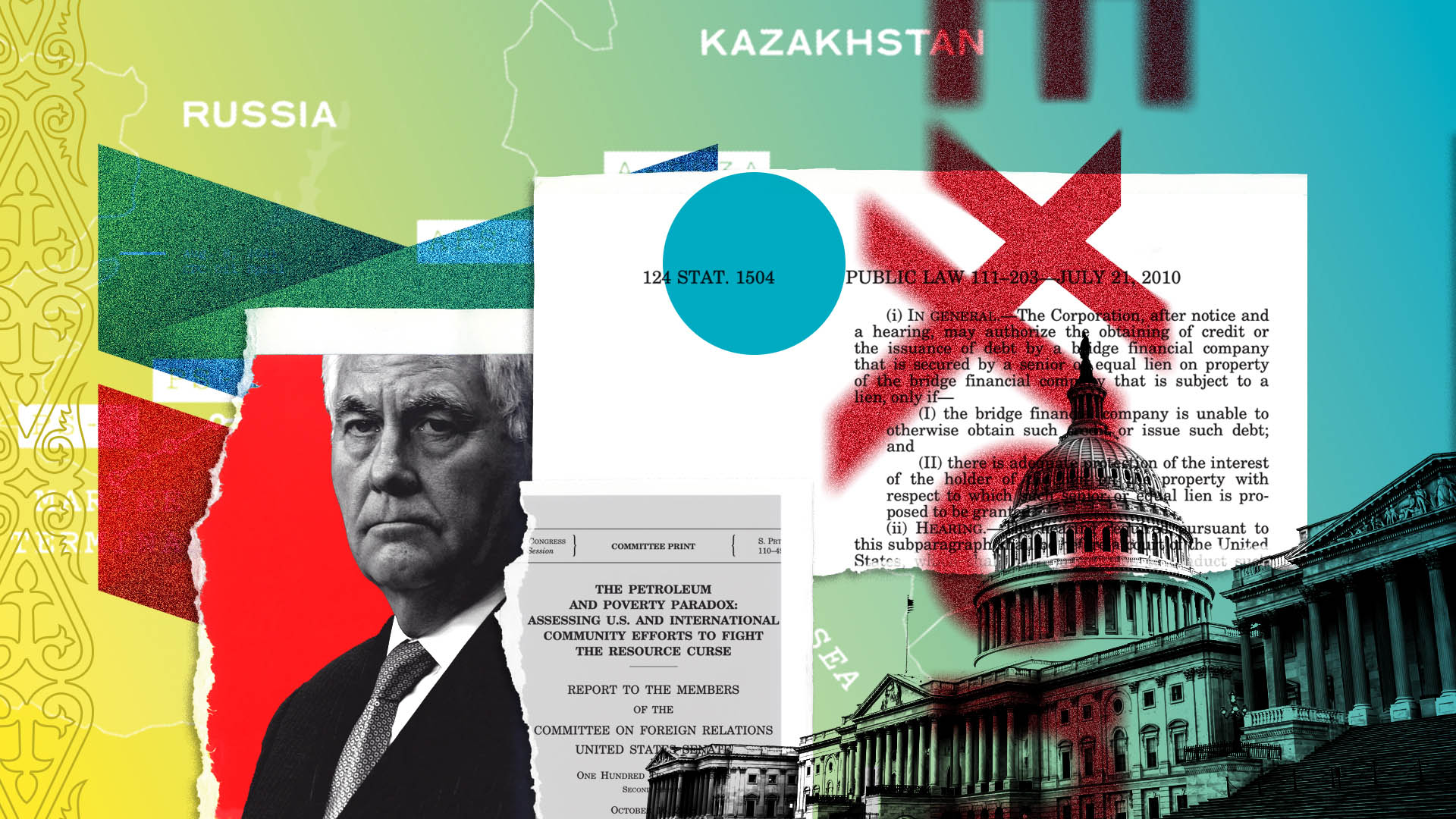

Caspian Cabals, a new investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and 26 media partners, exposes how the spill didn’t just lead to environmental damage, but also to allegations of financial corruption and geopolitical threats. Five whistleblowers have alleged in interviews with ICIJ that Western oil companies’ dealings in Russia or Kazakhstan included improper payments in violation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, a U.S. law that prohibits bribes to foreign officials.

Caspian Cabals: Key findings

The Caspian Cabals investigation reveals how Western oil companies — including Chevron Corp., ExxonMobil Corp., Shell PLC, and Italy’s Eni S.p.A. — ignored bribery risks and massive cost overruns to secure their stake in a critical Kazakhstan-Russia pipeline, only to be sidelined by the Kremlin. Here are seven key findings from our reporting.

The 939-mile pipeline, which has cost billions of dollars since construction began in 1999, carried hopes for international cooperation as well as future profits for both the investors and communities near the pipeline. It was also a means to reduce Western dependence on the Middle East. Increasingly, though, the pipeline’s Western owners, led by Chevron, had to cozy up to and buckle under Russian power to secure their investment and keep the oil flowing. Over 20 years, as Putin became more powerful, strategic-minded and a growing threat to Western interests, Chevron and the other shareholders increasingly ceded authority over the pipeline to the Russian president.

After the 2021 spill, the Western companies wrote to CPC’s director general to complain about Transneft and a string of “negative milestones” — including the oil spill, the first in the pipeline’s history. While their letter demanded answers, Western executives were confronting a new hard truth in the nearly 30-year history of CPC: The answers, when or if they did come, would be too little, too late.

Karachaganak

Kazakhstan

Kashagan

Tengiz

CPC pipeline

Caspian Sea

Russia

Port of

Novorossiysk

Azerbaijan

Georgia

Armenia

CPC terminal

Iran

Black Sea

Turkey

Karachaganak

Kazakhstan

Kashagan

Tengiz

CPC pipeline

Caspian Sea

Russia

Port of

Novorossiysk

Azerbaijan

Georgia

CPC terminal

Armenia

Iran

Black Sea

Turkey

Karachaganak

Russia

Ukraine

Kashagan

Kazakhstan

CPC pipeline

Tengiz

Port of

Novorossiysk

CPC terminal

Uzbekistan

Black Sea

Caspian Sea

Georgia

Azerbaijan

Armenia

Turkmenistan

Turkey

Iran

Karachaganak

Ukraine

Russia

Kazakhstan

Kashagan

CPC pipeline

Tengiz

Port of

Novorossiysk

Romania

CPC terminal

Black Sea

Uzbekistan

Bulgaria

Caspian Sea

Georgia

Azerbaijan

Armenia

Turkmenistan

Turkey

Mediterranean Sea

Syria

Iraq

Iran

Caspian Cabals explores the rise of a critical pipeline in the Caspian Sea region and the Kazakh oil fields that feed it. The two-year investigation is based on tens of thousands of pages of confidential emails, company presentations and other oil industry records, audits, court documents and regulatory filings, as well as hundreds of interviews, including with former company employees and insiders. The investigation exposes a pattern of problematic contracts and deals that illustrate how Western oil giants turned a blind eye to bribery risks, potential conflicts of interest and cost overruns. It reveals how Western oil company money has empowered anti-democratic actors in Kazakhstan, bolstered the neighboring regime of Vladimir Putin and enriched regional elites.

“It’s not just the oil companies who were complicit — so was the U.S. government,” Edward C. Chow, a former executive for Chevron Overseas Petroleum Ltd., said about allegations of oil-industry corruption in Russia. “They all knew, or they should have known, and chose to look the other way.”

For Chevron, there is little turning back. The second largest U.S. oil company — with its longtime home in San Ramon, Calif., and its center of gravity and new headquarters in Houston — has one of its biggest financial assets running through Russia and Kazakhstan. The company has said it expects to see $4 billion of free cash flow next year and $5 billion in 2026 from its joint venture at the Tengiz oil field in western Kazakhstan, which feeds the CPC pipeline. Chevron reported $21.4 billion in global net income last year. The company holds a 50 percent stake in the Tengiz operation, which averages billions of dollars in yearly income. Chevron declined to say exactly how much it earns on its Kazakhstan or Russia operations.

In a statement to ICIJ, Sally Jones, a senior media adviser for Chevron, said Chevron and the international oil companies “have sought to provide critical technical support to enable safe and reliable operations of the Caspian Pipeline Consortium.”

“Chevron is committed to ethical business practices, operating responsibly, conducting its business with integrity and in accordance with the laws and regulations of each of the jurisdictions in which it operates,” she said. She did not respond directly to questions about Chevron’s role in the pipeline or complaints about overpriced contracts, alleged kickbacks or conflicts of interest.

Exxon did not respond to requests for comment, nor did the governments of Kazakhstan or Russia. A spokesman for Shell said the company does not tolerate bribery in any form. An Eni spokesperson said, “We are committed to upholding the highest standards of transparency, ethical conduct and environmental responsibility.” Eni referred questions about the pipeline to CPC, which did not respond to multiple requests for comment from ICIJ.

Transneft also didn’t reply.

The new ICIJ investigation also reveals Russia’s relentless quest for dominance over the Western oil companies. Putin’s gradual control over the CPC — complete with ultimatums and an unbreakable will to emerge on top — aligned with his larger presence on the international stage as a prime minister and president who would assert his influence where he saw fit. Whether it was invading Chechnya, Georgia or Ukraine, meddling in U.S. presidential elections, or making barely veiled threats of using his nuclear arsenal, Putin saw a way to use CPC as a weapon in a long-standing and troubling rivalry with the West. And he was showing the formidable adversary he would come to be.

‘To reward friends and punish enemies’

The Caspian pipeline originates at the 156-square-mile Tengiz oil field on the remote northeastern coast of the Caspian Sea, the largest lake in the world. With some sections of pipe above ground and others at least 23 feet underground, the line crosses treeless prairies and rivers in Kazakhstan, and mountains, rice paddies and cornfields in southern Russia. More than two-thirds of it is on Russian territory. The pipeline, which is up to 56 inches in diameter with color-coded identification marks, ends in the Black Sea at three orange buoys about three miles from the CPC pipeline’s terminal building. These floating platforms are anchored to the seabed about 165 feet below.

Kazakhstan, the second biggest country in the Caspian region — and the one with the most oil — shares long borders with Russia to the north and northwest and China to the east.

In the late ’80s, with Kazakhstan still a Soviet state, the potential for reshaping the geopolitics of a region rich in oil became clear. The relationship between the West and Soviet Union President Mikhail Gorbachev was thawing. Gorbachev was looking for ways to revive his nation’s creaky economy. Stifled by 70 years of dictatorship, the Soviet Union needed Western money and technology. The West needed oil.

How Kazakhstan’s oil boom fueled a wealth gap

Formerly a member of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan is the largest country in Central Asia, and the ninth largest country in the world. Despite being rich with natural resources, the country has suffered from a persistent wealth gap.

The United States became the first country to recognize Kazakhstan’s independence, under President George H.W. Bush in 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed. For decades since, U.S. presidents, diplomats and lobbyists have promoted the Caspian region as a resource bonanza, a New Persian Gulf.

Almost overnight, it seemed, the Caspian region took center stage, showing up on magazine covers and even in a James Bond thriller about a Caspian pipeline. In Kazakhstan, U.S. officials at first sought to secure the country’s nuclear weapons and help Chevron, at the time the fourth largest U.S. oil company, gain access to the Tengiz oil field. As oil companies scrambled for Caspian stakes, Washington articulated new policy objectives such as enhancing commercial opportunities for U.S. companies and promoting the West’s free-market and other business practices in the region.

The West also had hopes of freeing Caspian countries from dependence on Russia. But before any of that could take hold, there was a major hurdle: how to get the Tengiz oil to world markets from the Caspian Sea bordering Kazakhstan, which was surrounded by nations that were commercial rivals and had their own oil transport routes.

James Giffen, a merchant banker, knew a lot about dealing with hurdles. He had started traveling to Moscow in 1969 while consulting with American companies interested in entering the Soviet market. Soviet officials had suggested that he get involved in bringing oil field technology and equipment to the Soviet Union because the future of the country depended on the development of its oil and gas industry.

In the spring of 1987, a golf partner, financier Nicholas Brady — who would soon be named President Ronald Reagan’s Treasury secretary — offered to help connect Giffen with executives at Chevron. Chevron appeared more than eager, according to an account that Giffen, who died in 2022, gave to Columbia University’s Harriman Institute. The oil giant was trying to secure its future in an uncertain time for Western oil companies.

Within days, Giffen said, he and a colleague were on a flight to San Francisco to meet Chevron’s chairman and CEO, George Keller. At the end of the meeting, after two hours and lunch, Keller declared: “We’re in,” according to Giffen.

Working for Chevron, Giffen brought along politicians, lobbyists, lawyers, consultants, trade groups and think tanks used by Chevron and other oil companies to promote their new interests in the Caspian region.

Chevron executives courted Kazakh officials at a casino, at Disneyland, on a beach in Spain. In the Columbia interview, Giffen said the oil companies “made extravagant gifts” to woo decision-makers, including building stadiums for the Kazakhs, which he believed to be a violation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. “It’s just unbelievable what they did,” Giffen said. “But no charges were ever brought against the oil companies.”

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Chevron and Giffen parted ways. Giffen went to work for the new Kazakh president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, as his chief oil negotiator and, prosecutors later alleged, his personal banker.

Chevron’s overseas president, Richard Matzke, who originally joined Chevron as a geologist in Louisiana, had his sights on what he called Kazakhstan’s “super-giant” Tengiz oil field, one of the world’s richest and deepest, on the northeast shore of the Caspian Sea.

In April 1993, after more than five years of grueling negotiations, Chevron struck a deal with Kazakhstan to develop Tengiz. Kazakhstan and Chevron each got 50%. Chevron received a license to produce oil for 40 years through 2033. The joint venture was called Tengizchevroil. With that decision, oil industry consultant Thane Gustafson wrote that Chevron “practically bet the company” on Tengiz.

As oil executives from at least four other Western oil companies pushed to buy chunks of the Kashagan and Karachaganak oil and gas fields in Kazakhstan, Giffen negotiated for Nazarbayev.

Between 1995 and 2000, Mercator Corp., the small merchant bank that Giffen founded and controlled, was paid about $67 million in “success fees,” and Giffen allegedly diverted $78 million from the oil companies to two senior Kazakhstan officials, according to 2003 indictments filed in U.S. federal court. The officials were President Nazarbayev and Nurlan Balgimbayev, who served first as Kazakhstan’s minister for oil and gas and then prime minister.

Prosecutors charged Giffen in a bribery scheme. Much of the money, they said, was deposited in Swiss bank accounts. Balgimbayev allegedly used funds to buy $180,000 worth of diamond jewelry and $20,000 to reserve a week’s stay at a Swiss spa, the indictment said. Giffen spent $80,000 on a Donzi speedboat for a Kazakh official and $30,000 for fur coats for Nazarbayev’s wife and daughter, according to the indictment. He paid for his daughter’s tuition at George Washington University, in Washington, out of the same funds, the indictment said. Neither Nazarbayev nor Balgimbayev was charged; Giffen pleaded guilty to a tax-related misdemeanor. But a judge declined to sentence him to prison after he testified that he acted with support from the CIA and the White House to help advance American interests in the region.

The oil field contracts between the government of Kazakhstan and the oil companies remain secret to this day — fairly standard practice in the industry.

With the oil extraction deals set, Chevron needed a transportation route to get the oil out of non-coastal Kazakhstan. While some Chevron executives pushed for a way to bypass Russia, Matzke, Chevron’s overseas president, kept his focus on an uncompleted pipeline in southern Russia. U.S. officials promoted expanding the CPC pipeline through Russia, too, but they also stressed the need for multiple oil routes.

The route through Russia, though, was fraught from the earliest discussions about Tengiz. For starters, the CPC left out Western companies. It wasn’t until 1996 that CPC’s structure was radically revised to give Chevron and other private companies (many of them Western) a combined 50% stake in the venture. The other 50% was divided among states: Russia, Kazakhstan and Oman. And all pipelines in Russia ran through that country’s state-owned pipeline monopoly, Transneft. Neither Transneft nor Moscow was about to take a back seat. And the Kremlin was particularly invested in what came next, because Russia didn’t have a direct partner in the project.

As Nazarbayev later recalled, he had to go and convince Russian President Boris Yeltsin, who was in a Kremlin hospital. When Nazarbayev showed the ailing president a map of the pipeline, Yeltsin called up Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin and asked whether the pipeline was “profitable” for Russia. After getting assurance, Yeltsin said: “Then I’ll sign it.”

Chow, the former Chevron manager, said that Transneft was important for political as well as economic reasons. “In Russia’s patronage system,” he said, “you can use the control of the pipeline to reward friends and punish enemies.”

The most eager oilman with close ties to the Kremlin was Vagit Alekperov, CEO of the fledgling Lukoil company and now Russia’s richest man. A former oil rig worker from Azerbaijan, Alekperov rose to become deputy oil and gas minister of the Soviet Union before taking over large Russian oil fields and setting up Lukoil, now Russia’s second largest oil company. American journalist Paul Klebnikov wrote in “Godfather of the Kremlin” that Alekperov and Russian Fuel and Energy Minister Yuri Shafranik put the “Baku squeeze” on Chevron and Kazakhstan in 1995: They saw to it that Chevron received only a third of the pipeline capacity it had been promised. Then Lukoil received a share of the Tengiz oil project. The revised deals, completed in 1996 and 1997, reflected the delicate balance of power in the region. Of all the pipeline owners, the Russian government would end up holding the largest share, 24% at the time. Kazakhstan held 19% and Oman, which overlooks the mouth of the Persian Gulf and shares a border with Saudi Arabia, 7%. The private shareholders — including Chevron, Exxon, Amoco, Eni and Shell — held a combined 50% ownership. Chevron owned the largest piece of that slice, 15%. Estimates were that Russia could get as much as $33 billion in direct and indirect revenue over 35 years. And while Russia agreed to donate unused pipeline assets, the private companies would put up the money to construct the pipeline. These developments sprang from Russia’s enormous sense of “national pride” and “entitlement” that were driving forces predating Putin, said Adrian Dellecker, a political scientist who wrote about CPC for the French Institute for International Relations in 2008.

“CPC only happened because Russia was weak and the West dictated it,” Dellecker told ICIJ. When Putin came to power, “The whole calculation changes,” he said. “It becomes about Russia regaining its former glory. For Putin, the CPC project is not about quarterly profits, or even annual profits. It’s about gaining control.”

Bending to Moscow

The deals to start the oil flowing were underway in 1999, but plans for democracy in the Caspian region would fade because of a profound breakdown of intelligence and failure to predict Putin’s desire to rebuild the old Soviet Union.

“This was a great dream of the U.S. to make these countries independent,” said former CIA agent Robert Baer, who was assigned to Central Asia and the Caucasus. “It just wasn’t doable.”

Baer told ICIJ that U.S. government officials’ talk about promoting democracy was “public messaging” and “willful blindness” to government corruption and dictatorship in Russia and Kazakhstan. “It was all about oil,” Baer said. “The reality of oil.”

In the end, the U.S. allocated only modest resources to the sort of training, aid and institution building necessary to achieve its goals, said Robert A. Manning, a former senior U.S. State Department official and author of “The Asian Energy Factor: Myths and Dilemmas of Energy, Security and the Pacific Future.” He called the U.S. goals of expanding democracy in the Caspian region a “romantic dream.”

But on a crisp day in May that year there was much celebration of the pipeline’s promise. At CPC’s groundbreaking ceremony in the Black Sea village of Yuzhnaya Ozereevka, oil executives, diplomats and politicians on one side of the road feasted on caviar and sipped champagne. On the other side, a spirited group of up to 100 activists had wrangled their way into the ceremony, despite orders from the mayor of the port city of Novorossiysk that police stop them.

VIPs including Chevron’s Richard Matzke and Lukoil’s Vagit Alekperov hailed the start of CPC terminal construction, which had been in the planning stage for many years, as a model of international cooperation. Protesters jeered the loudest when U.S. special adviser Richard Morningstar read a letter of congratulations from President Bill Clinton.

They aimed to block the pipeline from cutting through a coastline nature reserve, placing an ever greater environmental burden on Novorossiysk. They maintained that Chevron and the other CPC owners had broken Russia’s law on environmental assessment and that they were being denied adequate compensation for their land.

Yuzhnaya Ozereevka, a settlement of around 1,100 people 10 miles from the port, featured unique forest slopes and pistachio and juniper trees that residents had sought to protect since the 1980s; now they were under threat from the billion-dollar pipeline, residents said in a lawsuit against CPC in 2000. They also pointed to ongoing issues with air pollution from two oil terminals and other enterprises already operating in the area. CPC denied the allegations, and a judge found in favor of the company.

Meanwhile, the West was hopeful about Russia’s next president, Vladimir Putin, who officially took over as acting president on the last day of the 20th century. Western nations reacted optimistically when the new leader vowed to stand firm for freedom of speech and the rule of law. In Clinton’s congratulatory phone call to the former KGB agent, the American president remarked that Yeltsin’s resignation and Putin’s response “are very encouraging for the future of Russian democracy.”

Putin’s rise, though, signaled a fundamental shift in the Caspian. In a 1999 meeting in Moscow with Alekperov and Matzke to assess the pipeline’s progress, Putin voiced a keen interest in it, according to Matzke. After the meeting, Putin stressed the economic and geopolitical importance of CPC to Russia, according to Petroleum Economist, a website that covers the industry. Indeed, for some, the early Putin years heralded a moment of cooperation between Russia and the U.S. — at least on issues such as nuclear nonproliferation and, in the wake of 9/11, counterterrorism. As U.S. Secretary of Commerce Donald Evans said later at the pipeline’s opening ceremony in Moscow, CPC was the “start of Russian-American dialogue.”

The view of CPC from the offices of Transneft, Russia’s state pipeline monopoly, was more cynical than Putin’s, however. Transneft, then led by former Lukoil executive Semyon Vainshtok, who went on to have direct access to Putin, wanted total control of oil transport by Russia. Throughout the 2000s, Vainshtok wasted few opportunities to remind the public that CPC’s low revenue for the Russian state was “humiliating.”

“For transporting oil across its territory, the country has not received a cent,” Vainshtok would complain to Neftegaz.ru, an energy news website, in 2006.

Meanwhile, Novorossiysk residents worried about what would happen if a pipeline accident spilled oil onto their land. They turned to Mikhail Konstantinidi, a secondary school history teacher and local civic activist, to fight for them in court. They alleged in lawsuits filed in 1999 and 2000 that CPC had not complied with environmental laws. “The rude intrusion of CPC into nature was simply unacceptable,” Konstantinidi, now 66, told ICIJ. “And as practice and time showed, all of our concerns were confirmed.”

Activists in Novorossiysk also demanded a referendum on the location of the pipeline, which local officials said was of such “national importance” that homeowners in Yuzhnaya Ozereevka had to sign over their land. Soon after, a crew bulldozed the vineyards and the forest.

With Konstantinidi’s help, campaigners won a limited victory in September 2000. A Novorossiysk judge ordered a halt to pipeline construction. The judge found that CPC had failed to obtain required environmental approvals and did not have permission to begin construction. But CPC successfully appealed the ruling. Police detained Konstantinidi two weeks later on fraud charges, which he said were trumped up in retaliation for his pipeline opposition. A judge convicted him, and he served more than two years in prison.

By the time the teacher turned activist would be freed on appeal in 2004, local resistance to CPC had largely been quashed, he told ICIJ.

As the oil expansion plans at Tengiz moved forward, CPC needed to dramatically open up the pipeline’s capacity. Officials wanted to more than double its output by enlarging the diameter of the pipes and adding 10 pumping stations to increase the velocity of the oil flow. The estimated cost was $1.5 billion.

Putin, who had promised his support for CPC, was now under more scrutiny from the West over his brutal military campaign in Chechnya, a republic in southern Russia that had declared independence. After a brief Chechen success in the First Russo-Chechen War, Russia, under Putin, had launched a second war in 1999, crushing the movement with overwhelming military force. The result was deaths, disappearances and displacement of hundreds of thousands of civilians, leaving Chechnya firmly under Moscow’s control.

To build on Russia’s stated cooperation, Chevron executive Ian MacDonald, who was named CPC director in 2002, led an international campaign to promote the proposed pipeline expansion.

“It is vital to the interests of Russia that CPC continues to succeed,” MacDonald said at the Moscow International Oil and Gas Exhibition in June 2002. “CPC unlocks the key to the Caspian’s wealth.” But the surge of Western oil money flowing into Russia and Kazakhstan in the 2000s only further bolstered the burgeoning dictatorships in both countries.

As Russia aimed to boost its economic gains from oil and gas exports — as well as regain its earlier place of power in the world — the government tightened its grip on CPC. “The stronger Transneft became financially and the more its leadership was affiliated with Putin, the stronger it emerged as an entity issuing [the message] that it considers CPC a problem” — a non-government pipeline that was a competitor to Transneft, Vladimir Milov, a Russian opposition leader and former Russian deputy energy minister, told ICIJ.

From Russia, the Kazakhs had learned how to take “advantage of every minor transaction to extract maximum value” from the oil companies, John Dabbar, a ConocoPhillips executive at the time and a former CPC business manager, would later tell a U.S. ambassador, according to a U.S. diplomatic cable obtained by WikiLeaks.

“In Russia, everybody in the Ministry of Energy needs a revenue stream and a lever, and sometimes they will pull that lever just to remind you that they can,” the cable quoted Dabbar as saying.

In October 2007 the Russians applied additional leverage when Putin tapped an old KGB colleague, Nikolai Tokarev, to lead Transneft, which had been tasked with managing Russia’s CPC stake. Days later, Chevron bent to pressure from Moscow. The company changed its perspective and agreed with a proposal to create CPC’s first board of directors, which would have ultimate say over the pipeline. Russia had five of the board’s 22 seats, more than any shareholder, according to a report by International Oil Daily, a proprietary energy information company. The election of a Chevron representative, Andrew McGrahan, as board chairman was a “compromise” from the perspective of Western shareholders.

While Chevron executives played up progress and success, the reality was that the oil giant contemplated withdrawing from the venture. Chevron executive Guy Hollingsworth would later tell U.S. officials that the company had largely “written off” CPC expansion. The Russians “keep ratcheting up demands until there is nothing left,” he said, according to WikiLeaks.

Russian influence on CPC increased in late 2008, after it bought Oman’s 7% share and boosted its stake in the pipeline to 31%; now Russia could block decisions at the board level.

By late 2010, when CPC shareholders were finally set to approve the expansion budget, the cost had ballooned from $1.5 billion to a remarkable $5.4 billion. Chevron cited “adjustments in scope” for the escalating price tag, including additional power supply costs in Russia, a significant increase in labor hours and rates, and “uncertainty regarding the readiness” of CPC and the three companies managing the expansion.

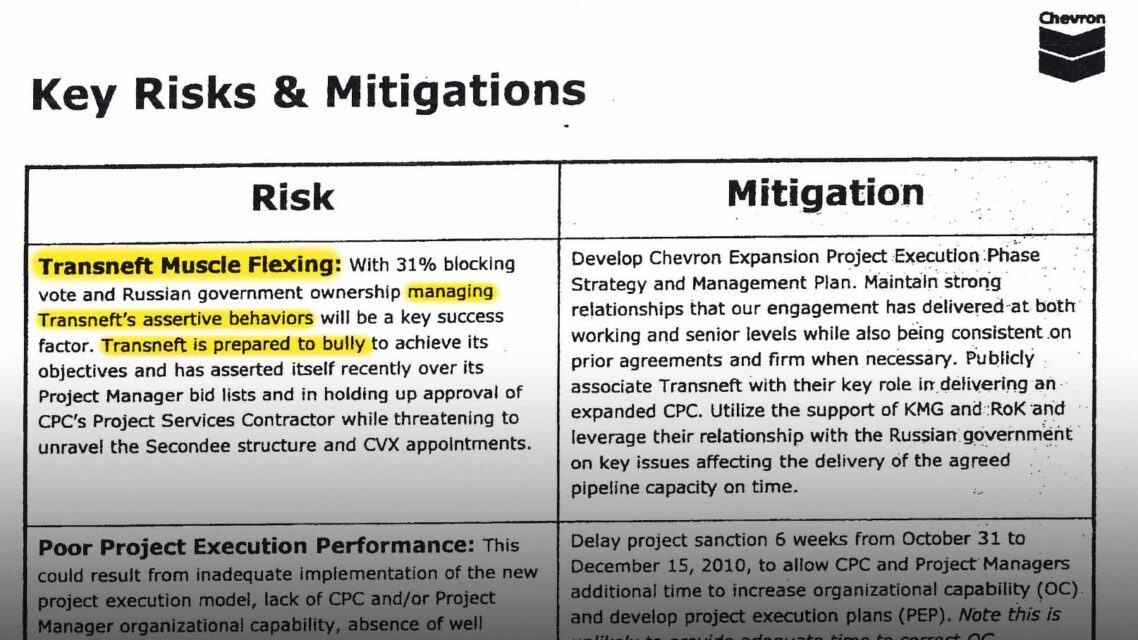

The confidential Chevron documents warned that Transneft was “muscle flexing” and using “bully tactics” to give contracts to Russian companies. For example, Transneft held up contract awards, sought to steer deals to unqualified bidders and filibustered for maximum control. Internal Chevron documents obtained by ICIJ show the company opposed Transneft’s effort to steer contracts to its own affiliates because such awards created built-in conflicts of interest, since Transneft was not in a position to oversee itself. Transneft’s “filibuster” over the contract process came to a head on the day the bid packages for pumping stations were opened: Transneft blocked CPC representatives from entering its building to review the bids, according to one confidential Chevron presentation. The CPC shareholders approved the expansion deal anyway. Despite all the strong-arm tactics, compromises and Russia’s clear ascendence, there was still so much money to be made.

A new power grab

“I went to great lengths to get my hands on this secret report and finally succeeded,” Russian anti-corruption blogger Alexei Navalny wrote in his posthumously published book “Patriot: A Memoir.”

“I was appalled,” he wrote, adding, “It was a huge scandal.”

Navalny was writing about a leaked internal audit into alleged embezzlement on Transneft’s Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean pipeline, a bombshell document that broke open the scale of corruption inside Russian state companies in late 2010.

Based on the leaked internal audit Navalny obtained, Transneft contractors had regularly raised work costs, rigged tenders, performed unnecessary work and inflated expenses on materials.

Transneft’s Tokarev dismissed Navalny’s allegations and suggested he was a shill for the CIA.

As Navalny took on state energy companies in his crusade against corruption, he became the most outspoken critic of Putin and his inner circle — and an international icon for justice. He was jailed on extremism and other charges but denied all of them. Navalny, 47, died in “Polar Wolf,” one of Russia’s toughest penal colonies, located north of the Arctic Circle in Siberia.

A month after Navalny’s audit leak, despite whatever misgivings Chevron and the other shareholders might have had, they signed off on the CPC expansion deal.

“The more Russia became rich, the more assertive the policies of Putin’s government were, the more endangered the Western investments in the oil and gas industry became,” said Milov, the former Russian energy official and one-time adviser to Navalny.

The Russian audit on Transneft raised concerns about several contractors to which Chevron and its CPC partners had awarded work for the $5.4 billion CPC expansion. The pipeline upgrade — to increase capacity to 67 million tons of oil a year — began in July 2011 after a decade of negotiations. Pipe with a larger diameter would be welded onto older pipe. Larger valves would be installed, and vast storage tanks would be added. There would also be 10 additional pumping stations.

Through reviewing court and other public records as well as leaked documents such as expansion progress reports, ICIJ discovered that CPC contractors in Russia and Kazakhstan ran up millions of dollars in charges through contract amendments, performed poor-quality work such as welding defects in pipes and in at least one case paid a fake subcontractor.

In 10 cases identified by ICIJ, Russian construction firms signed contracts for the CPC expansion and accepted advance payments or loans, but they allegedly failed to carry out substantial work or delivered work late. One case, a tax dispute brought by a major CPC contractor in the Russian courts in 2015, revealed that a $48 million advance payment was made for work that included building electricity lines to a new pumping station in southern Russia that never happened. Most of those funds, court records show, were initially destined for modular homes for construction workers. Instead, a few days later, according to a Russian judge, $35.6 million ended up at a financial services company set up by a former colleague of Andrei Bolotov, son-in-law of Nikolai Tokarev, whom Putin had installed as the Transneft president.

The next year, Bolotov took a 50% interest in the finance company — a stake that he later transferred to his wife at the time, Tokarev’s daughter, Russian corporate records show. A Russian court noted that the original construction contractor’s actions “were aimed exclusively at removing funds from circulation” but did not find any wrongdoing on the part of the financial services company.

Bolotov did not respond to multiple requests for comment from ICIJ. In an email to ICIJ, a former director and shareholder of the financial services company strongly denied that his company had ever received the funds in question.

Less than a year after the pipeline expansion got underway, a former Chevron executive turned whistleblower accused Chevron and five other oil companies, along with four Chevron executives, of approving hugely overpriced contracts. The whistleblower’s lawyer, Stephen M. Kohn, asked the oil companies to investigate.

“The information and documents provided by our client(s) demonstrate that Chevron, through its Chevron Caspian Pipeline Consortium Company, has entered into a project that it knows will funnel huge amounts of money to officials in the Russian government (and the colleagues and relatives thereof) via massive overpayments” to companies with connections to Transneft and the Russian government, Kohn wrote in a November 2011 confidential letter to Chevron. He sent similar letters to Exxon, Shell, Eni and BG Group PLC (later acquired by Shell).

Exxon’s lawyers said they found no evidence to support the complaint. “Your letters to date suggest the possibility that you are engaged in a fishing expedition,” attorney Theodore V. Wells Jr. wrote.

And BG Group’s lawyers replied that the company was reviewing the allegations but that many were based on supposition and too general to respond to. Shell PLC, at the time known as Royal Dutch Shell, acquired BG Group in 2016. Shell declined to respond to questions from ICIJ.

Kohn filed a complaint with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission the following year, claiming that the oil companies violated the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act; that 1977 law prohibits companies from promising anything of value to foreign government officials to influence decisions. Kohn’s complaint alleged red flags: disguising kickbacks as management fees, reducing peer review requirements essential for proper oversight, and steering contracts to companies politically favorable to the Russian government.

The complaint went nowhere, but in 2022 Kohn filed complaints with the SEC and Commodity Futures Trading Commission on behalf of two oil company whistleblowers with allegations similar to the earlier complaint. Kohn’s letters to the oil companies from the earlier complaint alleged that one way Transneft funneled money to government officials was through the politically influential company Velesstroy, which grew into a major Transneft supplier and was allegedly awarded contracts vastly above market rate.

Sanctioned by the U.S. in 2023, Velesstroy is owned by businessmen from Croatia named Mihajlo Perenčević and Krešimir Filipović; the U.K. sanctioned both men as individuals (one as early as 2022 and the other last year) because of their ties to the energy sector in Russia. Filipović, who owned nearly 85% of Velesstroy in 2020, is a close business associate of the Russian government. The media dubbed him “Putin’s wallet” in the Balkans. In 2017, Putin presented Filipović with a certificate of honor in gratitude for work in “construction, development and operation of new gas and condensate fields.”

The records reviewed by ICIJ, including bank documents, inspection reports and court filings, show how Velesstroy avoided taxes, used illegal and poorly trained labor, and violated safety rules.

Since 2015 at least 18 Velesstroy workers have died on the job, including a man who was buried under rubble after an avalanche at a CPC site. In a press release, CPC management expressed its “deepest condolences.” Neither Velesstroy nor Mihajlo Perenčević and Krešimir Filipović responded to multiple requests for comment.

Records obtained by Oštro, an ICIJ media partner, reveal that by 2020 Filipović and Perenčević controlled hundreds of millions of dollars in high-end properties in Croatia and Russia. A Russian bank granted a loan to help fund these acquisitions, and a company linked to Russian oligarchs managed the properties.

In May of this year, Russian news outlet and ICIJ media partner Proekt found that Velesstroy was paid $4.3 million in 2021 to refurbish the 4.4-acre Putin Palace. According to Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, the property features a helipad, a 27,000-square-foot greenhouse, an ice hockey rink, an indoor pool leading to an “aqua disco,” an amphitheater undergoing endless renovations, a chapel with an imperial-looking throne and a tunnel dug under the property to access the private beach — about 50 miles from CPC’s terminal.

Neither Velesstroy nor its owners responded to multiple requests for comment from ICIJ. The Russian President’s press office also didn’t reply.

As for the ongoing frustrations with the CPC expansion, one Western oil executive said in an email that the way contracts were written and managed was “terrible” and that CPC managers who sought to increase oversight were discredited. A confidential email from November 2012 quotes a CPC compliance officer calling CPC’s system of managing contracts a “snakepit” under Transneft. “Transneft is taking full advantage,” it said.

The problems spiraled down to the construction itself. An internal CPC report found “blatant disregard” for construction quality was “common on the expansion project, driven by a need to deliver results according to schedule.” But, the report noted, this situation “introduce[d] a greater likelihood of injury and / or failure when equipment goes live.”

In interviews with ICIJ, five whistleblowers said they had reported inflated costs on Caspian oil deals and efforts to steer contracts to politically influential companies. Their complaints alleging violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act have gone nowhere, they said. ICIJ also reviewed documents from four other whistleblowers or former insiders that alleged similar cost inflation or conflicts of interest.

Baer, the former CIA agent, said the major oil companies were aware of the corruption risks and all the fine points of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. “But they also understood that you can’t go into Central Asia without effectively paying bribes by overpaying for services, contracts and leases.”

Tensions within the consortium were ratcheting up. Former CPC international personnel said they faced visa problems and other intimidation they suspected Transneft had initiated. In 2016, CPC hired as its new general director Nikolay Gorban, a Transneft veteran who had worked at several of the company’s subsidiaries throughout the 2000s. With Gorban at the helm, a new power grab was in the offing. And so was a new calamity.

Turbulent waters

In April 2018, CPC General Director Gorban gave the command to start the pipeline pump station in Kalmykia, Russia — the final milestone of an expansion that had lagged four years behind schedule. The next year, the CPC partners launched plans for a $600 million project to again boost the pipeline’s capacity. Once more Transneft was ready to flex its muscles.

Transneft pushed to take away a buoy maintenance contract from a Dutch firm called Smit Lamnalco, which Chevron preferred, and award it to its subsidiary Transneft Service, according to sources with knowledge of the situation. The three bright orange buoys, each as tall as a two-story building and attached to the seabed by multi-ton anchors, were highly complex pieces of equipment floating about three miles from CPC’s marine terminal. Specially designed to withstand severe winds, these platforms transferred more than 50 million tons of oil onto hundreds of tankers every year.

According to documents obtained by Proekt, Transneft Service was paying Complex, a firm that owns Putin’s Palace, nearly every month for a non-residential real estate lease. Transneft Service paid the same firm a small monthly fee for buffet services. The payments for the lease and the buffet services from 2019 to 2023: more than $18.9 million.

In 2021, Navalny’s team published details on how Transneft subsidiaries paid Complex about $1 million a month for real estate leases. Navalny dubbed Putin’s Palace “history’s biggest bribe,” constructed for the Russian president, Navalny said, with $1.35 billion provided by members of his inner circle in exchange for top jobs and lucrative projects.

Sources told ICIJ’s Dutch partner NRC that shareholders argued over a proposal to award Transneft Service a lucrative marine service contract, which included buoy maintenance.

Transneft then blocked the election of a new CPC board of directors in early March 2020. Afterward, according to internal CPC documents reviewed by ICIJ, Transneft proposed expanding Gorban’s powers and having employees of Western shareholders working at CPC report to the general director. Though a new board was elected in May that year, shareholders chose not to vote on Transneft’s proposals. Five days after the board’s election, more than a dozen Western oil company employees working with CPC got an unwelcome surprise: Russia’s Interior Ministry accused CPC of employing them in Russia illegally. Concerned over possible consequences, the Western workers fled the country and were shut out of CPC’s computer system. Six weeks later, CPC signed a 10-year contract with Transneft Service for marine services at Novorossiysk.

The pipeline had essentially morphed into “a very impressive and powerful political tool,” according to Vladimir Milov, the Russian opposition leader.

In March 2021 Transneft Service took control of marine work at Novorossiysk. The oil spill happened five months later.

A Russian-dominated investigation board blamed the accident on a damaged part in one of the buoys that caused a sudden rupture. The buoys’ manufacturer, Imodco, is part of SBM Offshore N.V., which has a subsidiary that pleaded guilty in a 2017 scheme to bribe officials in Brazil, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Kazakhstan and Iraq, and agreed to pay a $238 million fine. The board did not implicate Imodco in the spill.

In the years before the spill, a series of incidents revealed serious safety lapses within the CPC pipeline network, with Russian regulators repeatedly flagging deficiencies. Inspectors noted inadequate procedures for investigating accidents, including incidents in 2016 and 2017 in which reports lacked critical details on environmental damage and financial losses. Also, essential safety infrastructure such as fire-extinguishing equipment at pumping stations wasn’t maintained, and uncertified workers were allowed to handle hazardous tasks in the years after the spill occurred. All these issues heightened risks across the pipeline.

CPC never disclosed exactly how much oil was recovered from the sea, and a Russian court found that the pipeline company provided contradictory information to a Russian environmental agency. CPC “has repeatedly changed its position” on how much oil spilled, the court said.

Finding that the buoy system was “extremely poorly equipped with control devices,” the court fined CPC $98.7 million in April 2022.

Just two weeks earlier, the shareholders had written to Gorban, complaining about numerous damaged pipeline hoses and questioning Transneft Service’s experience, its equipment and its qualifications to “ensure safe and reliable operations.” Neither CPC’s internal investigation nor the court found Transneft Service responsible for the spill. But whatever leverage shareholders once had was long gone.

Weapon of war

Russia’s war on Ukraine presented all new worries for the Western oil companies. The U.S. had already sanctioned several Russian government officials and entities: in 2014 after Russia’s occupation of Crimea, and in 2018 for cyber and U.S. election interference. With the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine came new military action in the Black Sea: cruise missiles launching from Russian submarines; Russian warships targeting Ukrainian cities; Ukraine’s sinking of a Russian fleet flagship; and Ukrainian drones and missiles striking devastating blows against Putin’s fleet based in Crimea and Novorossiysk. And all of this was in proximity to the CPC pipeline.

The start of the war, then, led to frequent shutoffs of the pipeline tap.

During the war, ICIJ’s investigation found, CPC has faced at least 20 disruptions of activity or suspensions of oil shipments, most because of maintenance and repair of equipment, bad weather conditions preventing oil from being loaded onto tankers, and inspections of the seabed for decommissioned explosives dating to the Second World War.

ICIJ also discovered that Putin’s administration may have manipulated a claim of equipment damage by a storm to make the West and Kazakhstan worry about oil supplies. The apparent manipulation of information began two weeks after the U.S. moved, in early March 2022, to cut off Russia’s oil profits and other resources through sanctions. CPC released a statement saying it had suspended operation for two of its three oil buoys because of the storm damage and estimated that repairs could “take considerable time.” Originally, according to Arseny Pogosyan, who was a press secretary at the time for Russia’s deputy energy minister, the Russian government was going to release a simple statement about the damage, offering a similar assessment.

But in reviewing the initial message, Pogosyan said, Russian officials suggested the repairs would take longer than they actually would or should have, with Deputy Energy Minister Pavel Sorokin claiming, in what had now morphed into a video message, that the repairs could take six weeks to two months. “And naturally, given the length of these repairs, we’re talking about a potential loss of capacity up to 80% of oil loading,” Sorokin said. Pogosyan, the man behind the camera, told ICIJ that the Russian government sought to embellish the March pipeline shutdown to show the West that Russia could inflict pain through oil availability despite the sanctions.

Pogosyan said he had to redo the video with Sorokin — who constantly went back to Putin’s administration for consultation — 12 times.

“They tried to make the incident more significant to global media,” said Pogosyan, who left Russia in September 2022. “The main reason we did it so many times was the presidential administration’s intention to make the message harder, more significant, to scare the West.”

In January of this year, though, CPC General Director Gorban told Kazakh journalists, “There have never been any stoppages of our pipeline system, in any year, because of the political statements of anyone. All the stoppages were connected to technical causes, or to the weather. We are in no way connected to politics.”

Radio Free Europe reported in 2022 that the pipeline carries about 80% of Kazakhstan’s oil exports, much of it to Western markets. In 2023, the CPC pipeline carried 63.5 million tons of oil to international markets. Eighty-eight percent of that amount came from the Kazakh oil fields and the rest from Russia. Based on changes to expand the pipeline’s capacity, it can carry up to 83 million tons of oil annually. But when shipments are halted, oil prices rise and Europeans face potential fuel shortages.

“What happened in 2022, with the disruption to loading in the Black Sea, created shock waves through the industry,” Malcolm Forbes-Cable, vice president of energy consulting firm Wood Mackenzie, said at a conference this year.

“When half of this capacity was taken offline in March 2022, the oil market reacted by increasing the price by $5 [per barrel],” Forbes-Cable said. “That just shows you what a critical, global piece of infrastructure [CPC] is and how important it is to the global economy.”

Based on ICIJ’s reporting, however, the pipeline shutdowns have had limited impact on consumers worldwide, despite occasional, temporary price hikes. This finding goes against what Western governments have offered as to why CPC should be exempt from sanctions: to spare European energy consumers.

In her statement, Chevron’s Sally Jones underscored how CPC is a critical export route for Kazakh crude to international markets. “There are no other viable export options,” she said.

To keep CPC off the list of companies banned from doing business with Russia, the Western oil companies and Kazakhstan spent millions lobbying the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the Department of Energy, the State Department, members of Congress and the European Commission. They argued that shutting off the oil might harm consumers in Europe and have geopolitical consequences.

And that argument was constant: Five months into the war in Ukraine, the Kazakhstan state oil company KazMunayGas retained the American law and lobbying firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck. For a contract that is now worth about $3.8 million, the firm organized at least 101 meetings with U.S. officials to lobby for CPC, in addition to handling other related matters, according to disclosure forms filed by the lobbying firm under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA).

According to the FARA reports, Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck arranged at least eight meetings with Geoff Pyatt, U.S. assistant secretary of state and special envoy and coordinator for international energy affairs at the State Department. In remarks posted on the State Department website last year, Pyatt said that CPC had to be kept off the sanctions list because it is the “principal exit point for Kazakh crude to global markets.” It is also “an important source of supply, especially for a couple of key European allies,” he said.

The State Department “worked very closely” with the Treasury Department to keep the pipeline in operation, Pyatt acknowledged. “Chevron and ExxonMobil have invested tens of millions of dollars” in Kazakhstan, he said, and they “are all watching very carefully the vulnerability that arises from our collective reliance on CPC.”

Pyatt did not respond to several requests from ICIJ seeking comment, nor did Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck.

In a written statement to ICIJ, a State Department official emphasized inherent risks of doing business with Russia, citing concerns such as seizing private assets, manipulating energy resources for political ends, and seeking to punish firms that adhere to U.S. or partner sanctions. “Russia has weaponized its energy trade relationships to exert political influence, proving itself an unreliable long-term partner.”

The State Department official also reiterated long-standing support for diversity of pipeline export routes to bolster energy security and reduce dependency on a single partner.

In total, Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck reported 17 meetings with State Department representatives. The firm also organized meetings for its clients, KazMunayGas and the Kazakh Embassy, with nine senators and 48 U.S. representatives.

Neither KazMunayGas nor the government of Kazakhstan responded to requests for comment.

In Brussels, 10 weeks after the invasion of Ukraine, the cabinet of European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen received an email from an Exxon vice president expressing “urgent serious concern” regarding the impact of just proposed sanctions. But by then the EU was already tightening sanctions on Russia.

“The current text would prevent the exports of Kazakhstan crude through the CPC pipeline,” Nikolaas Baeckelmans, a vice president for EU affairs at Exxon, wrote to Kurt Vandenberghe, a member of von der Leyen’s cabinet, in May 2022.

“This (CPC) crude should continue to flow and not be subject to/clearly exempted from sanctions,” Baeckelmans wrote. “Please note that the US sanctions do contain an explicit exemption for this pipeline and I believe it always has been the intention to try and ensure the transatlantic alignment.”

Seventeen minutes later, Vandenberghe wrote back, reassuring the lobbyist that his message was “well received.”

In a written statement to ICIJ, an EU Commission spokesperson declined to provide details about how the commission made the decision not to sanction the CPC pipeline. “All decisions on sanctions in the EU are taken unanimously by the Member States in the Council,” the spokesperson wrote. The Council of the EU is one of its decision-making bodies.

For a thousand days, it has been crucial to radically reduce Russia’s ability to fund its war through oil sales. Oil is the lifeblood of Putin’s regime. — Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, addressing European Parliament on the 1,000-day anniversary of Russia’s invasion

Beyond the arguments against sanctions, the truth is that sanctions would also cost Chevron, Exxon and the other companies lost sales and a delay in their expansion plans.

One country that some would assume to be in favor of sanctions takes a different point of view. On November 19, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy called for “strong sanctions” in his address to the European Parliament’s extraordinary plenary session marking 1,000 days since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“For a thousand days, it has been crucial to radically reduce Russia’s ability to fund its war through oil sales,” he said. “Oil is the lifeblood of Putin’s regime.”

Russian oil enters the CPC pipeline primarily from Lukoil’s offshore fields in the Russian sector of the Caspian Sea, as well as through rail transport from smaller fields in southern Russia. In July 2022, advocacy group Global Witness revealed that a Russian oil company with ties to sanctioned oligarch Roman Abramovich was exporting oil through the CPC system.

Still, Agia Zagrebelska, policy director of the Economic Security Council of Ukraine, explained to ICIJ in an interview why Ukraine had not called for sanctions on CPC or the CPC pipeline.

“The work of the CPC is reflected both at the European level and in [other] countries,” she said. “Therefore, today we are forced to look not only at what Americans and Europeans think, but also what Central Asia thinks.”

U.S. officials are still pushing for a pipeline route that bypasses Russia while trying to move Kazakhstan toward the West politically. “It’s in our DNA,” said Manning, the former State Department official. “We’re always trying to promote democracy in places that are very different from us. It hasn’t turned out very well.”

Russia’s war in Ukraine is in its third year, with 30,000 civilian deaths; 3.7 million people internally displaced; and 6.5 million having fled the country. Amidst all that carnage and loss, the pipeline, through hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes that CPC pays to Russian authorities, helps to boost arms production and pay state officials’ salaries and pensions.

Meanwhile, Putin continues to keep Western governments on edge. Russia’s nuclear threats are ever-present, and there are worries of an invasion of Kazakhstan under the pretext of reuniting “Soviet” lands. All of this plays out amid sanctions on Russian oil and pipelines being selectively exempted, helping to keep the Russian economy afloat.

For Putin, the end of the Soviet Union was, as he told Russians in his 2005 state of the nation address, “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century” — and the ultimate show of weakness. From the beginning, Putin intended to display strength however and wherever he could. With the CPC pipeline, his determination to serve only Russia while undermining the West wasn’t just an early test of his autocratic style of leadership. It was about a new display of power. And a warning to the world of what he might do with such power.

Contributors: Carola Houtekamer, Karlijn Kuijpers (NRC); Stefan Melichar (Profil); Carina Huppertz, Frederik Obermaier, Bastian Obermayer, Hannes Munzinger (Der Spiegel/Standard/Paper Trail Media); Anuška Delić (Oštro); Roman Badanin, Mikhail Rubin (Proekt); Denise Ajiri, Naubet Bisenov, Kathleen Cahill, Jelena Cosic, Marcos Garcia Rey, Whitney Joiner, Karrie Kehoe, Marcia Myers, Delphine Reuter, Matei Rosca, David Rowell, Richard H.P. Sia, Dean Starkman, Thomas Rowley, Gerard Ryle, Nicole Sadek, Fergus Shiel, Annys Shin, Tom Stites, Peter Stone, Angie Wu (ICIJ)