A new leak of highly classified Chinese government documents has uncovered the operations manual for running the mass detention camps in Xinjiang and exposed the mechanics of the region’s Orwellian system of mass surveillance and “predictive policing.”

The China Cables, obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, include a classified list of guidelines, personally approved by the region’s top security chief, that effectively serves as a manual for operating the camps now holding hundreds of thousands of Muslim Uighurs and other minorities. The leak also features previously undisclosed intelligence briefings that reveal, in the government’s own words, how Chinese police are guided by a massive data collection and analysis system that uses artificial intelligence to select entire categories of Xinjiang residents for detention.

The manual, called a “telegram,” instructs camp personnel on such matters as how to prevent escapes, how to maintain total secrecy about the camps’ existence, methods of forced indoctrination, how to control disease outbreaks, and when to let detainees see relatives or even use the toilet. The document, dating to 2017, lays bare a behavior-modification “points” system to mete out punishments and rewards to inmates.

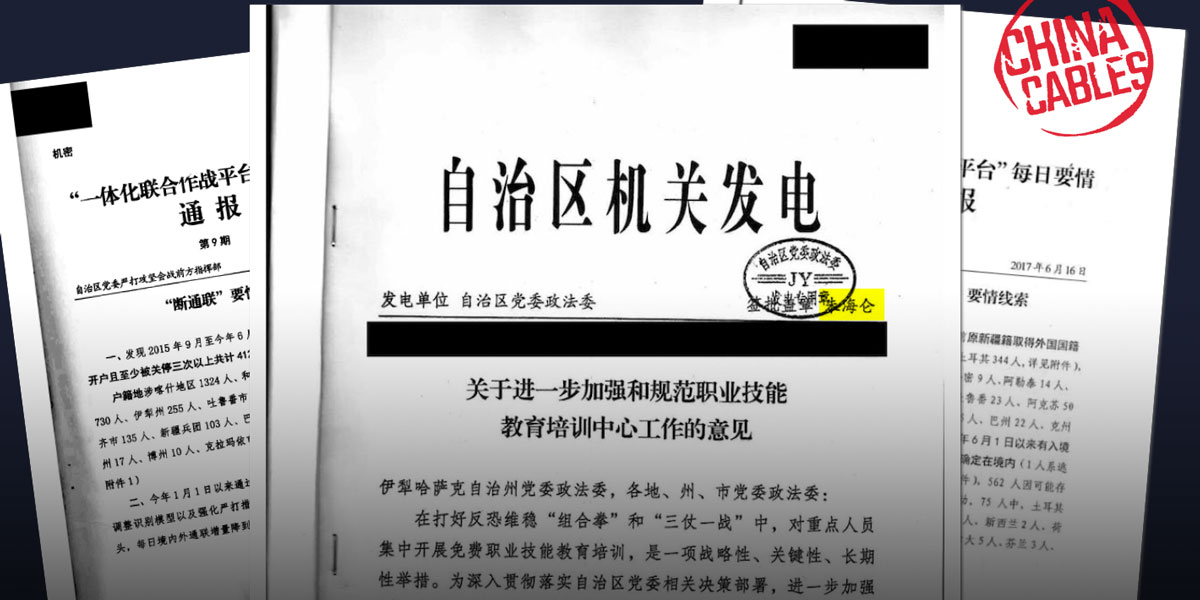

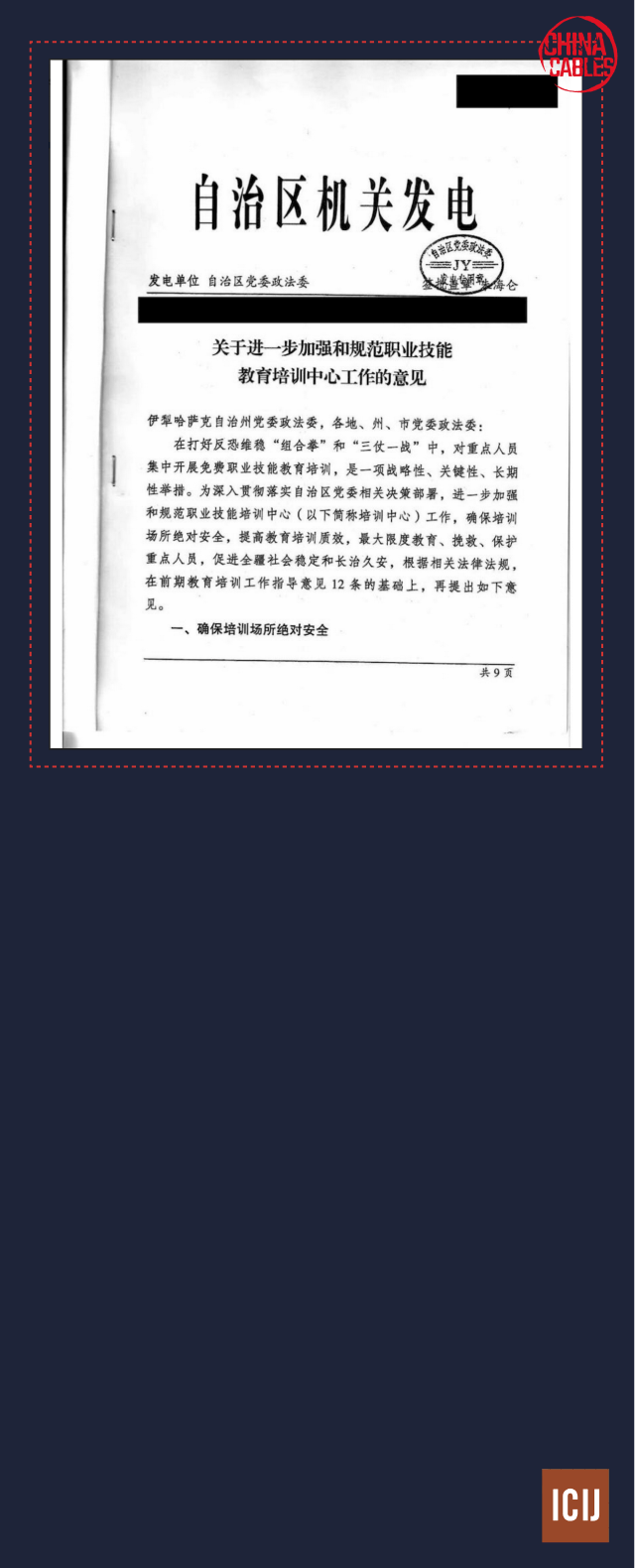

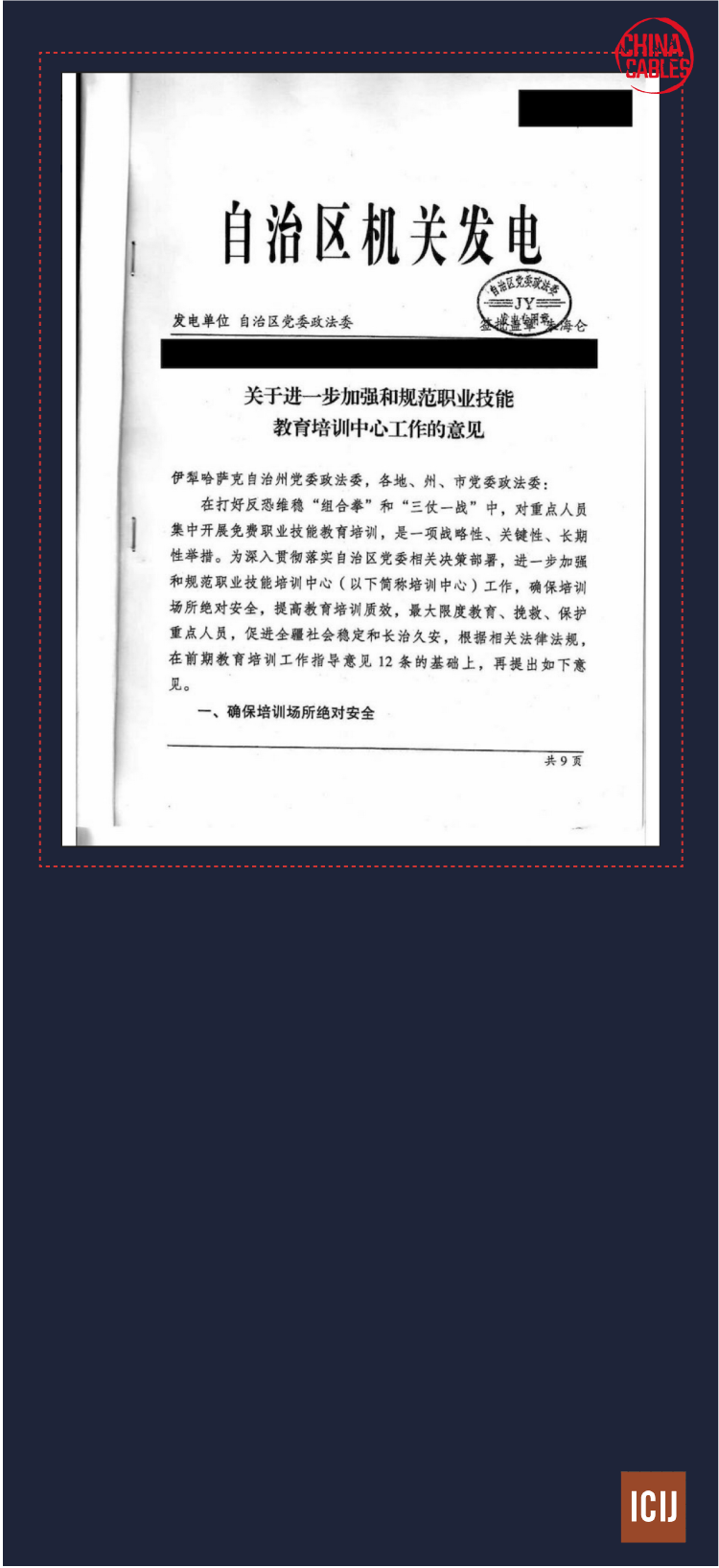

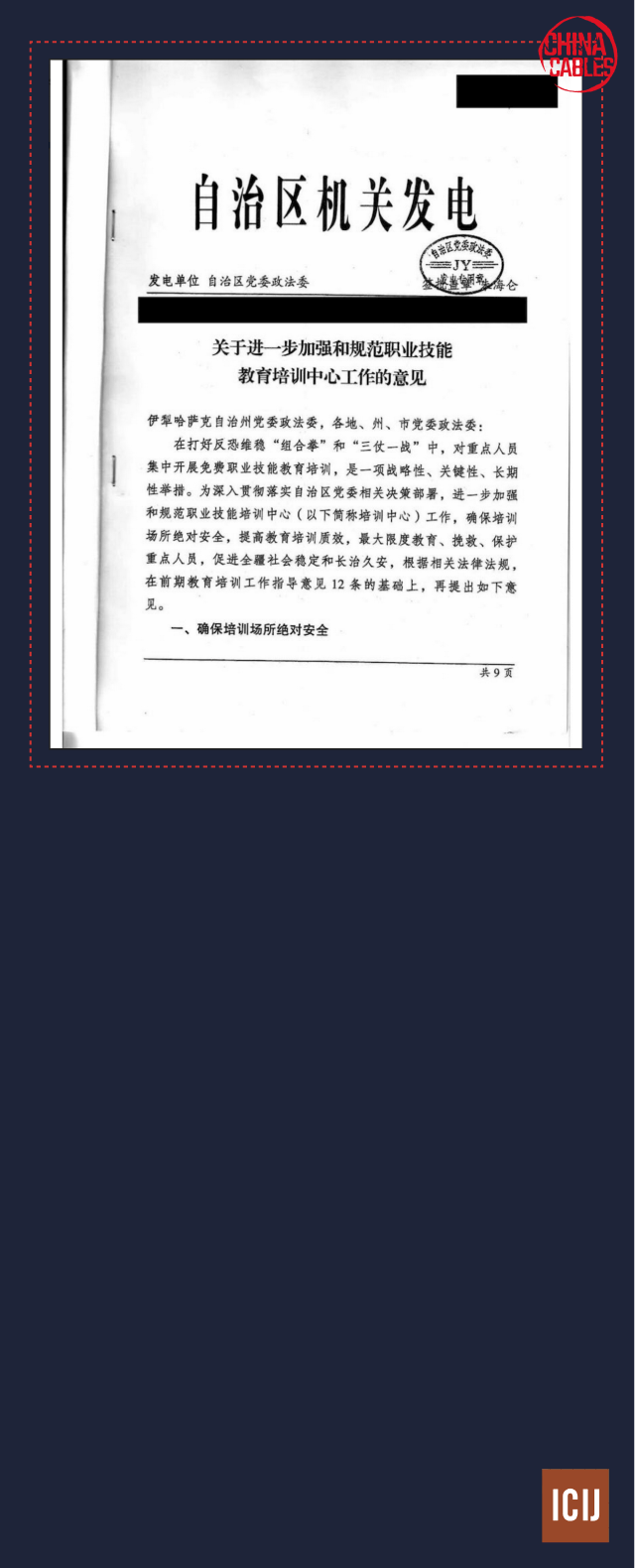

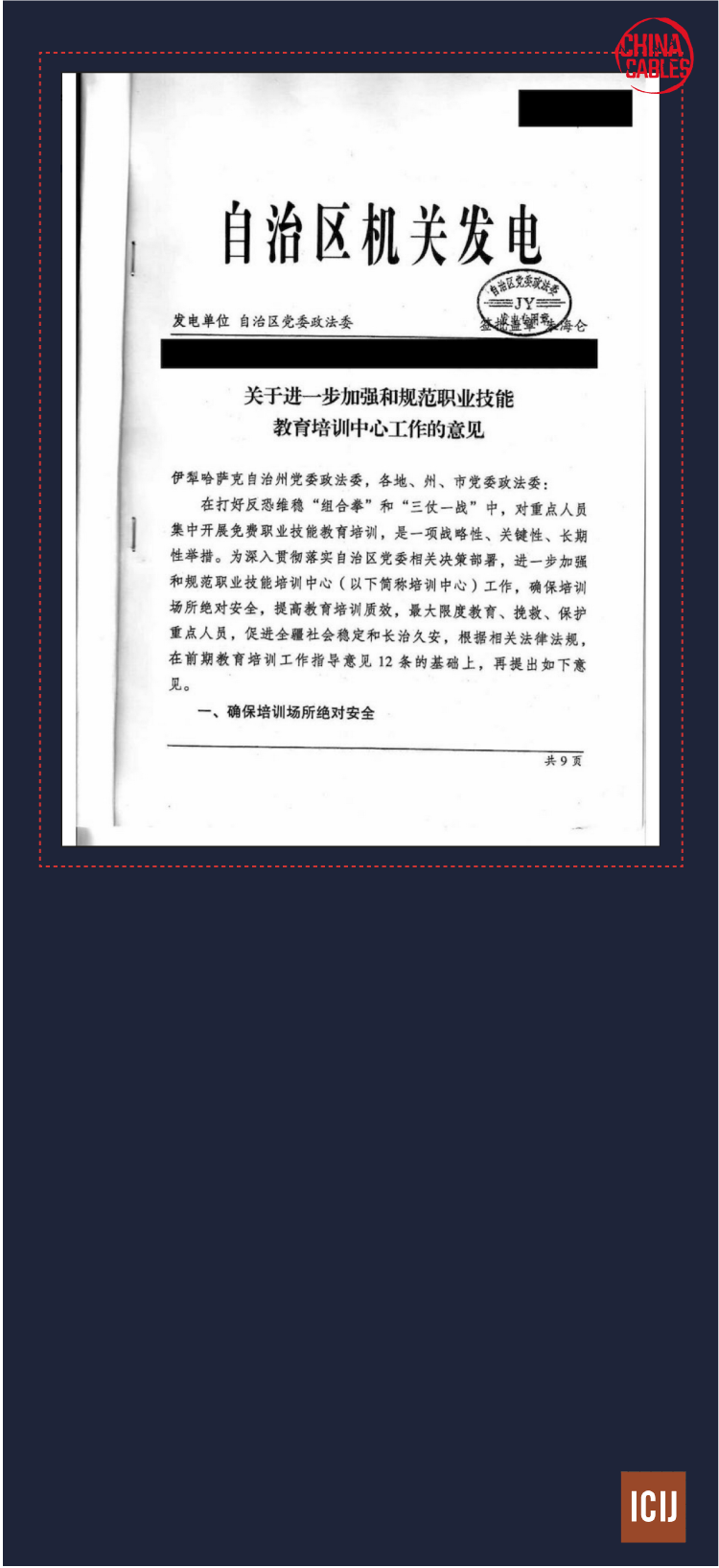

Telegram

This telegram is from the Communist Party commission in charge of Xinjiang’s security apparatus. The telegram, written in Chinese, is an operations manual for running the mass detention camps. It is marked “secret” and was approved by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official.

Telegram

This telegram is from the Communist Party commission in charge of Xinjiang’s security apparatus. The telegram, written in Chinese, is an operations manual for running the mass detention camps. It is marked “secret” and was approved by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official.

Telegram

This telegram is from the Communist Party commission in charge of Xinjiang’s security apparatus. The telegram, written in Chinese, is an operations manual for running the mass detention camps. It is marked “secret” and was approved by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official.

Telegram

This telegram is from the Communist Party commission in charge of Xinjiang’s security apparatus. The telegram, written in Chinese, is an operations manual for running the mass detention camps. It is marked “secret” and was approved by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official.

The manual reveals the minimum duration of detention: one year — though accounts from ex-detainees suggest that some are released sooner.

The classified intelligence briefings reveal the scope and ambition of the government’s artificial-intelligence-powered policing platform, which purports to predict crimes based on these computer-generated findings alone. Experts say the platform, which is used in both policing and military contexts, demonstrates the power of technology to help drive industrial-scale human rights abuses.

The China Cables reveal how the system is able to amass vast amounts of intimate personal data through warrantless manual searches, facial recognition cameras, and other means to identify candidates for detention, flagging for investigation hundreds of thousands merely for using certain popular mobile phone apps. The documents detail explicit directives to arrest Uighurs with foreign citizenship and to track Xinjiang Uighurs living abroad, some of whom have been deported back to China by authoritarian governments. Among those implicated as taking part in the global dragnet: China’s embassies and consulates.

New clarity on vast internment camps

The China Cables mark a significant advance in the world’s knowledge about the largest mass internment of an ethnic-religious minority since World War II. Over the past two years, reports based on ex-inmate accounts, other anecdotal sources and satellite images have described a system of government-run camps in Xinjiang large enough to hold a million or more people. They have also sketched the outlines of a massive data-collection, surveillance and policing program across the region. A recent New York Times article shed light on the historical lead-up to the camps.

The China Cables represents the first leak of a classified Chinese government document revealing the inner workings of the camps, the severity of conditions behind the fences, and the dehumanizing instructions regulating inmates’ mundane daily routines. The briefings are the first leak of classified government documents on the mass-surveillance and predictive policing effort.

“It really shows that from the onset, the Chinese government had a plan for how to secure the vocational training centers, how to lock in the ‘students’ into their dorms, how to keep them there for at least one year,” said Adrian Zenz, a senior fellow in China studies at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation in Washington, D.C., who has reviewed the documents. “It’s very, very important that these documents are from 2017, because that’s when the whole reeducation campaign started.”

Responding to questions about the camps and surveillance program from ICIJ media partner the Guardian, the Chinese government called the leaked documents “pure fabrication and fake news.” In a statement this weekend, the press office of its UK embassy said: “First, there are no so-called ‘detention camps’ in Xinjiang. Vocational education and training centres have been established for the prevention of terrorism.”

“Xinjiang is a beautiful, peaceful and prosperous region in China. Three years ago, this was not the case,” the statement said. “It had become a battle ground – thousands of terrorist incidents happened in Xinjiang between 1990s and 2016, and thousands of innocent people got killed. So there’s an enormous uproar among the Xinjiang people for the government to take resolute measures to tackle this issue. Since the measures have been taken, there’s no single terrorist incident in the past three years. Xinjiang again turns into a prosperous, beautiful and peaceful region. The preventative measures have nothing to do with the eradication of religious groups. Religious freedom is fully respected in Xinjiang.”

The statement also said: “Second, the trainees take various courses at the vocational education and training centres, and their personal freedom of the trainees is fully guaranteed.”

It continued: “The [M]andarin is widely used in China and thus taught as one of the courses at the centres. The trainees also learn professional skills and legal knowledge so that they can live on their own profession. That’s the major purpose of the centres. The trainees could go home regularly and ask for leave to take care of their children. If a couple are both trainees, their minor children are usually cared for by their relatives, and the local government helps take good care of the children. These measures have been successful – Xinjiang is much safer. Last year, the tourists increased 40%, and the local GDP increased more than 6%.”

Finally, the statement said, “Third, there are no such documents or orders for the so-called ‘detention camps.’” It adds: “There are many authoritative documents in China for the reference of Chinese and foreign media want to know more about the vocational education and training centres. For instance, seven relevant white papers have been published by the State Council Information Office.”

The China Cables documents have been verified by linguists and experts, including James Mulvenon, director of intelligence integration at SOS International LLC, an intelligence and information technology contractor for several U.S. government agencies. Mulvenon, an expert in the authentication of classified Chinese government documents, called the Chinese-language documents “very authentic,” adding that they “adhere 100% to all of the classified document templates that I’ve ever seen.”

More than 75 journalists from ICIJ and 17 media partner organizations in 14 countries joined together to report on the documents and their significance.

The leaked documents include:

- The operations manual, or “telegram,” nine Chinese-language pages dated November 2017 that contain more than two dozen detailed guidelines for managing the camps, which were then in the early months of operation.

- Four shorter Chinese-language intelligence briefings, known as “bulletins,” providing guidance on the daily use of the Integrated Joint Operation Platform, a mass-surveillance and predictive-policing program that analyzes data from Xinjiang and was revealed to the world by Human Rights Watch last year.

Both types of documents are marked “secret,” the middle of a three-tier Chinese secrecy ranking. The manual was approved by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official. The bulletins were distributed to police and local party officials in charge of security around the region. Zhu did not respond to questions sent to him via China’s international press contact point. Attempts to fax its Xinjiang equivalent failed.

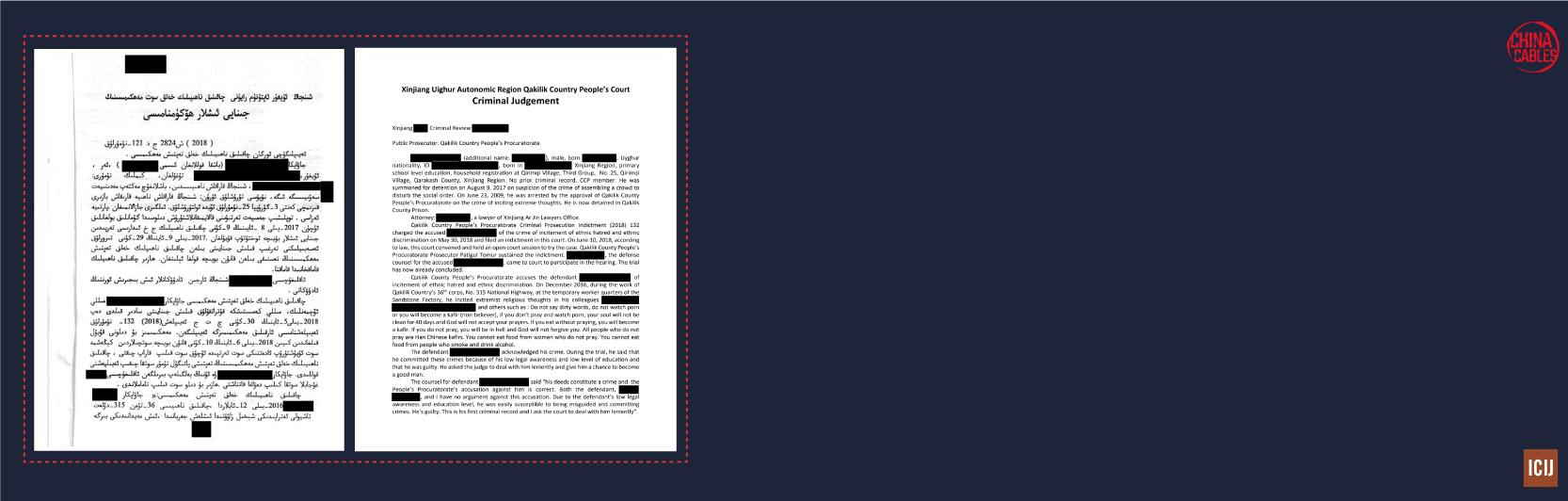

- A Uighur-language sentencing document from a regional criminal court that details the allegations against a Uighur man imprisoned for inciting “ethnic hatred” and “extreme thoughts.” The allegations feature such seemingly innocuous acts as admonishing co-workers not to use profanity or watch pornography. The document is unclassified, but in a political system with little transparency, Xinjiang court documents are rarely seen by outsiders.

Uighurs in the crosshairs

A predominantly Muslim community that speaks its own Turkic language, Uighurs have lived in the arid central Asian region now known as Xinjiang for more than 1,000 years, adopting Islam after contact with Muslim traders. Uighurs have long faced economic marginalization and political discrimination as an ethnic minority, now accounting for nearly 11 million people in a country where nearly 92% of the 1.4 billion population is of Han Chinese ethnicity. Most Chinese Uighurs live in Xinjiang, a region of mostly mountains and desert in the country’s far northwest. The nominally autonomous region — also home to Kazakhs, Tajiks, Hui Muslims and a large Han population — has been under formal Chinese control since the 18th century.

Largest ethnic groups in China

Group

Population

1. Zhuang

16,926,381

2. Hui

10,586,087

3. Manchu

10,387,958

4. Uighurs

10,069,346

5. Yi

9,714,393

6. Miao

9,426,007

7. Tujia

8,353,912

8. Tibetan

6,282,187

9. Mongolian

5,981,840

10. Dong

2,879,974

Largest ethnic groups in China

Group

Population

1. Zhuang

16,926,381

2. Hui

10,586,087

3. Manchu

10,387,958

4. Uighurs

10,069,346

5. Yi

9,714,393

6. Miao

9,426,007

7. Tujia

8,353,912

8. Tibetan

6,282,187

9. Mongolian

5,981,840

10. Dong

2,879,974

Largest ethnic groups in China

Group

Population

Group

Population

6. Miao

9,426,007

1. Zhuang

16,926,381

7. Tujia

8,353,912

2. Hui

10,586,087

8. Tibetan

6,282,187

3. Manchu

10,387,958

9. Mongolian

5,981,840

4. Uighurs

10,069,346

10. Dong

2,879,974

5. Yi

9,714,393

Largest ethnic groups in China

Group

Population

Group

Population

Group

Population

11. Bouyei

2,870,034

6. Miao

9,426,007

1. Zhuang

16,926,381

12. Yao

2,796,003

7. Tujia

8,353,912

2. Hui

10,586,087

13. Bai

1,933,510

3. Manchu

10,387,958

8. Tibetan

6,282,187

14. Korean

1,830,929

9. Mongolian

5,981,840

4. Uighurs

10,069,346

15. Hani

1,660,932

10. Dong

2,879,974

5. Yi

9,714,393

In recent years, Chinese President Xi Jinping has stepped up a nationwide campaign promoting conformity to Communist Party doctrine and Han cultural norms, and Uighurs, with their distinctive religious and ethnic identity, have increasingly come in the crosshairs.

Tensions between Uighurs, on one side, and the government and the region’s Han Chinese population, on the other, have sometimes turned violent. In 2009, Uighurs rioted in Xinjiang’s capital city of Urumqi, killing nearly 200 people, most of them Han Chinese. Beginning in 2013, Uighurs committed a series of deadly attacks on civilians in several Chinese cities, killing dozens. A Uighur Islamist group claimed responsibility for at least one of the attacks. Reports also emerged of dozens of Uighurs abroad joining the Islamic State. Beijing has responded with increasing ferocity. Blaming Uighur separatism and Islamic extremism, it imposed increasingly severe restrictions on religious practice in the region, outlawing beards, many forms of Muslim prayer and some forms of religious attire, including burkas and face veils.

By 2017, moving to curtail expressions of cultural, political and religious diversity, Xi ordered a quiet campaign of mass detention and forced assimilation in Xinjiang. Large numbers of people across the region began to disappear, according to witnesses and news reports, and rumors of secretive detention camps swirled. In some villages in southern Xinjiang, police had been ordered to sweep up nearly 40% of the adult population, it was reported later.

“At that time, it was terror among people,” said Tursunay Ziavdun, a 40-year-old Uighur woman now in Kazakhstan who spent 11 months in a camp in Xinjiang. “When we saw each other, people were terrified. The only thing we were talking about was saying, ‘ah you’re still here!’ In all the families there was someone arrested. Some, the whole family.”

“In February 2018, they arrested my older brother. Ten days later my little brother,” she said in an interview with ICIJ media partner Le Monde in November. “I thought, it’ll be my turn soon.” She was taken to a camp on March 10, 2018.

Detention camp in

Shufu County, Xinjiang

Satellite images show the rapid

construction and expansion of the

camp during 2017.

March 2017

July 2017

November 2017

Source: Satellite images captured from

Google Earth Pro.

Detention camp in

Shufu County, Xinjiang

Satellite images show the rapid construction

and expansion of the camp during 2017.

March 2017

July 2017

November 2017

Source: Satellite images captured from

Google Earth Pro.

Detention camp in Shufu County, Xinjiang

Satellite images show the rapid construction and expansion

of the camp during 2017.

November 2017

March 2017

July 2017

Source: Satellite images captured from Google Earth Pro.

Detention camp in Shufu County, Xinjiang

Satellite images show the rapid construction and expansion of the camp during 2017.

November 2017

March 2017

July 2017

Source: Satellite images captured from Google Earth Pro.

The Chinese government tried to keep the camps a secret. But beginning in late 2017, journalists, academics and other researchers — using satellite images, government procurement documents and eyewitness accounts — revealed a string of detention facilities, surrounded by fences and guard towers, across the region and the outlines of a new and alarming system of mass surveillance.

In October 2018, after the satellite images and eyewitness accounts made it undeniable, Xinjiang’s governor, Shohrat Zakir, acknowledged the existence of a system of what he called “professional vocational training institutions.” He said their purpose was to de-radicalize those suspected of terrorist or extremist leanings.

In an official white paper released in August, the government proclaimed the “vocational training centers” a resounding success, claiming that an absence of terror attacks in Xinjiang in the past three years was a result of the policy.

The China Cables starkly contradict the Chinese government’s official characterization of the camps as benevolent social programs that provide “residential vocational training” and meals “free of charge.” The documents specify that arrests should be made in almost any circumstance — unless suspicions can be “ruled out” – and reveal that a central goal of the campaign is general indoctrination.

Master plan with doublespeak

The lengthy “telegram” – inscribed with Zhu’s name at the top and labeled “ji mi”, Chinese for “secret” – presents a master plan for implementing mass internment, including more than two dozen numbered guidelines. Titled “Opinions on the Work of Further Strengthening and Standardizing Vocational Skills Education and Training Centers,” it was issued by the Xinjiang Autonomous Region’s Political and Legal Affairs Commission, the Communist Party committee responsible for security measures in Xinjiang.

Telegram

This telegram is from the Communist Party commission in charge of Xinjiang’s security apparatus. The telegram, written in Chinese, is an operations manual for running the mass detention camps. It is marked “secret” and was approved by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official.

Telegram

This telegram is from the Communist Party commission in charge of Xinjiang’s security apparatus. The telegram, written in Chinese, is an operations manual for running the mass detention camps. It is marked “secret” and was approved by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official.

Telegram

This telegram is from the Communist Party commission in charge of Xinjiang’s security apparatus. The telegram, written in Chinese, is an operations manual for running the mass detention camps. It is marked “secret” and was approved by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official.

Telegram

This telegram is from the Communist Party commission in charge of Xinjiang’s security apparatus. The telegram, written in Chinese, is an operations manual for running the mass detention camps. It is marked “secret” and was approved by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official.

The style combines standard Chinese bureaucratese with Orwellian doublespeak, blandly prescribing the secure management of toilet breaks and setting conditions for seeing loved ones while referring to inmates as “students” and listing the requirements to “graduate.”

The manual emphasizes that personnel must “prevent escapes” and mandates the use of guard posts, patrols, video surveillance, alarms and other security measures typical of prisons. Dormitory doors must be double-locked to “strictly manage and control student activities to prevent escapes during class, eating periods, toilet breaks, bath time, medical treatment, family visits, etc.,” the manual says.

“Students” are permitted to leave the camps only for reasons of “illness and other special circumstances,” it says, and camp personnel are required to “accompany, monitor, and control them” while away.

The memo also includes the provision – not always enforced, according to some former inmates – that detainees must remain in the camps for at least a year.

The manual reveals a points-based behavior-control system within the camps. Points are tabulated by assessing the inmates’ “ideological transformation, study and training, and compliance with discipline,” the manual says. The punishment-and-reward system helps determine, among other things, whether inmates are allowed contact with family and when they are released.

The manual also outlines a three-tiered system that classifies inmates by the degree of security required: “very strict,” “strict” or “general management.”

The manual does make provisions for inmates’ basic health and physical welfare, including explicit requirements that camp officials “never allow abnormal deaths.” It requires that personnel maintain hygienic conditions, prevent the outbreak of disease and make sure that camp facilities can withstand fire and earthquakes. “For training centers with more than one thousand people,” the manual says, “special personnel must be stationed to do food safety testing, sanitation and epidemic prevention work.”

The manual instructs personnel to “ensure that the students will have a phone conversation with their relatives at least once a week, and meet via video at least once a month, to make their family feel at ease and the students feel safe.”

Testimony of ex-inmates suggests that this guideline has been widely ignored. Last February, Uighurs outside of China and their supporters launched a Twitter campaign imploring the Chinese government to provide information about missing family members.

A Uighur businessman in Istanbul Asks CCP :where are my five children ?

住在土耳其伊斯坦布尔的维吾尔商人亚森江呐喊:中共:告诉我!我的五个孩子在哪里?

İstanbul’da yaşıyan Uygur iş adamı Yasinjan Çin hükümetine soriyor :Ey Cin:beş çocukum nerde ?

@UighurT@hrw@metoouyghur pic.twitter.com/AZdi9ad2b6— Tahir imin (@Uighurian) February 22, 2019

And despite the manual’s instruction to ensure health and safety, an unknown number of detainees have died in the camps due to poor living conditions and lack of medical treatment, according to eyewitness accounts. Mihrigul Tursun, a Uighur from Xinjiang now living in the United States, told a U.S. commission at a November 2018 hearing that while in detention, she saw nine women die under such circumstances.

Numerous ex-inmates have reported experiencing or witnessing torture and other abuses, including water torture, beatings and rape.

“Some prisoners were hung on the wall and beaten with electrified truncheons,” Sayragul Sauytbay, a former detainee who has been granted asylum in Sweden, told the Israeli newspaper Haaretz in October. “There were prisoners who were made to sit on a chair of nails. I saw people return from that room covered in blood. Some came back without fingernails.”

The “telegram” also includes an odd section on “manner education,” directing camp personnel to provide instruction in such areas as “etiquette,” “obedience,” “friendship behaviors” and the “regular change of clothes,” among other things. Darren Byler, a lecturer in anthropology at the University of Washington and an authority on Uighur culture, said the fixation on teaching normal adults how to bathe and make friends stems from a prevalent belief among Han Chinese that Uighurs are “backwards.”

“It’s like the discourse about the savage ‘other’ or the uncivilized ‘other,’ where you need to teach them how to be civilized,” Byler said. “But it’s been operationalized in Xinjiang.”

A camp-to-factory pipeline

China’s authorities have championed what they call “poverty alleviation” policies in Xinjiang. New vocational skills, the Chinese authorities say, allow Uighurs to pursue employment beyond fields and farms and thus improve their standard of living.

But researchers and journalists have uncovered a vast system of forced labor across the region, concentrated in textiles and other consumer goods manufacturing.

The manual mentions additional facilities for former camp detainees that appear to support these reports. “All students who have completed initial training will be sent to vocational skills improvement class for intensive skills training for a school term of 3 to 6 months,” the manual reads. “All prefectures should set up special places and special facilities in order to create the environment for trainees to receive intensive training.”

In a guideline called “employment services,” the manual then instructs camp officials to implement a policy called “one cohort graduates, one cohort finds employment” — suggesting that those who complete vocational training are to be placed in a work facility.

Finally, the manual tasks local police stations and judicial offices with providing “follow-up help and education” to former detainees after they are placed in employment, and instructed that after release, “students should not leave the line of sight for one year.”

The directives support reports that detainees are sent from camps to job sites under constant police watch.

“The ethnic minority population is being moved into closed, surveilled and state-controlled training and work environments that facilitate on-going indoctrination,” wrote Zenz in a July 2019 report.

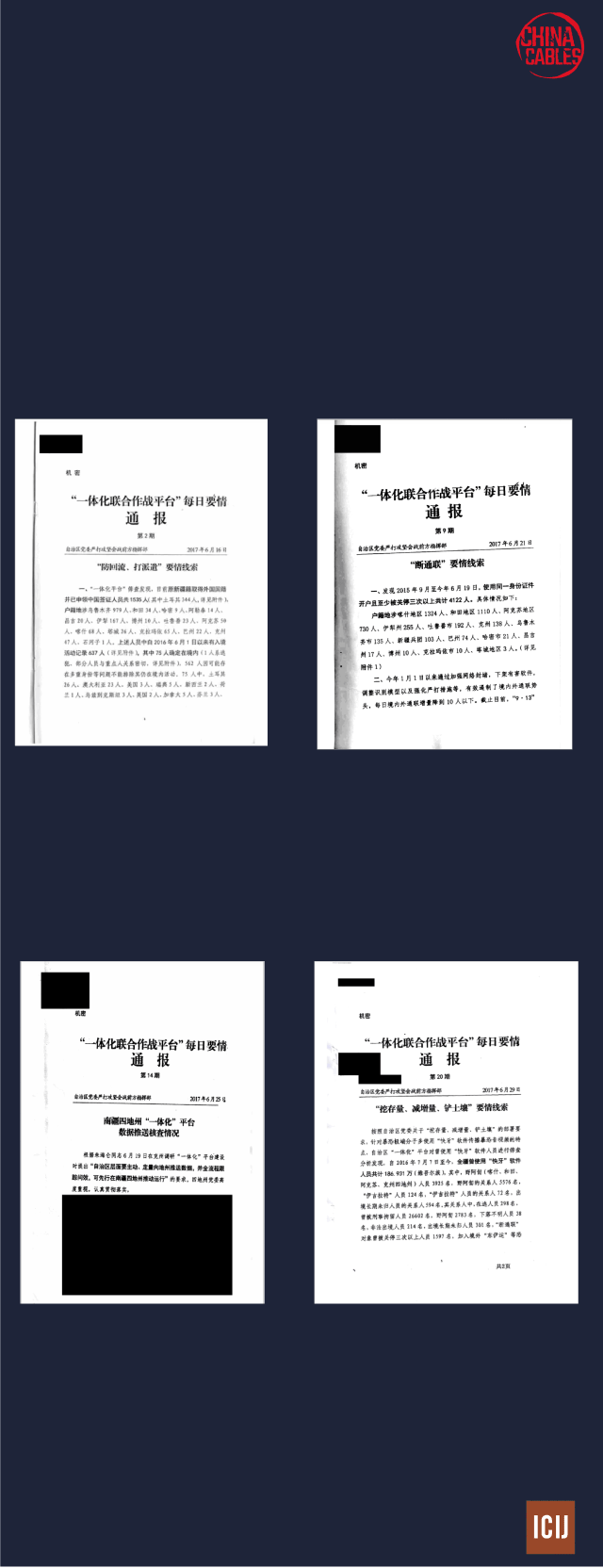

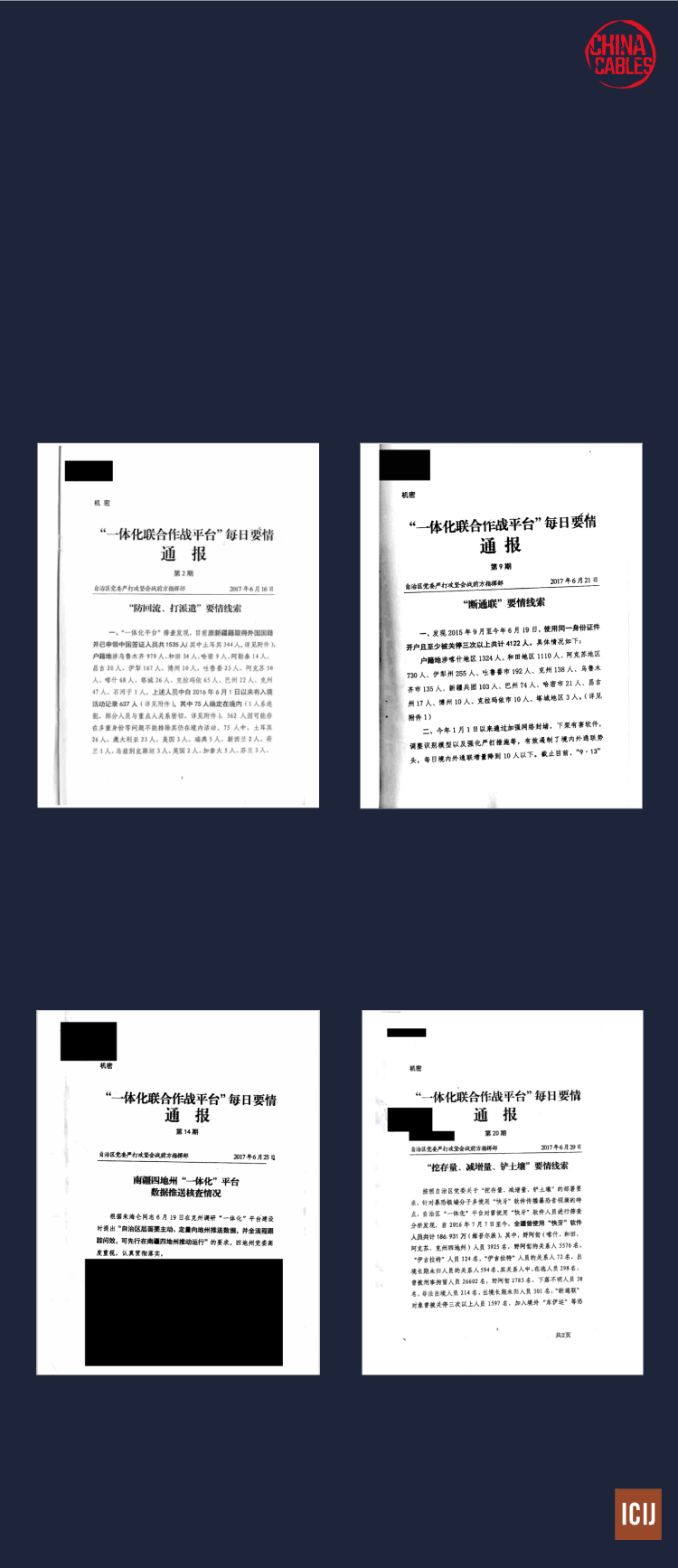

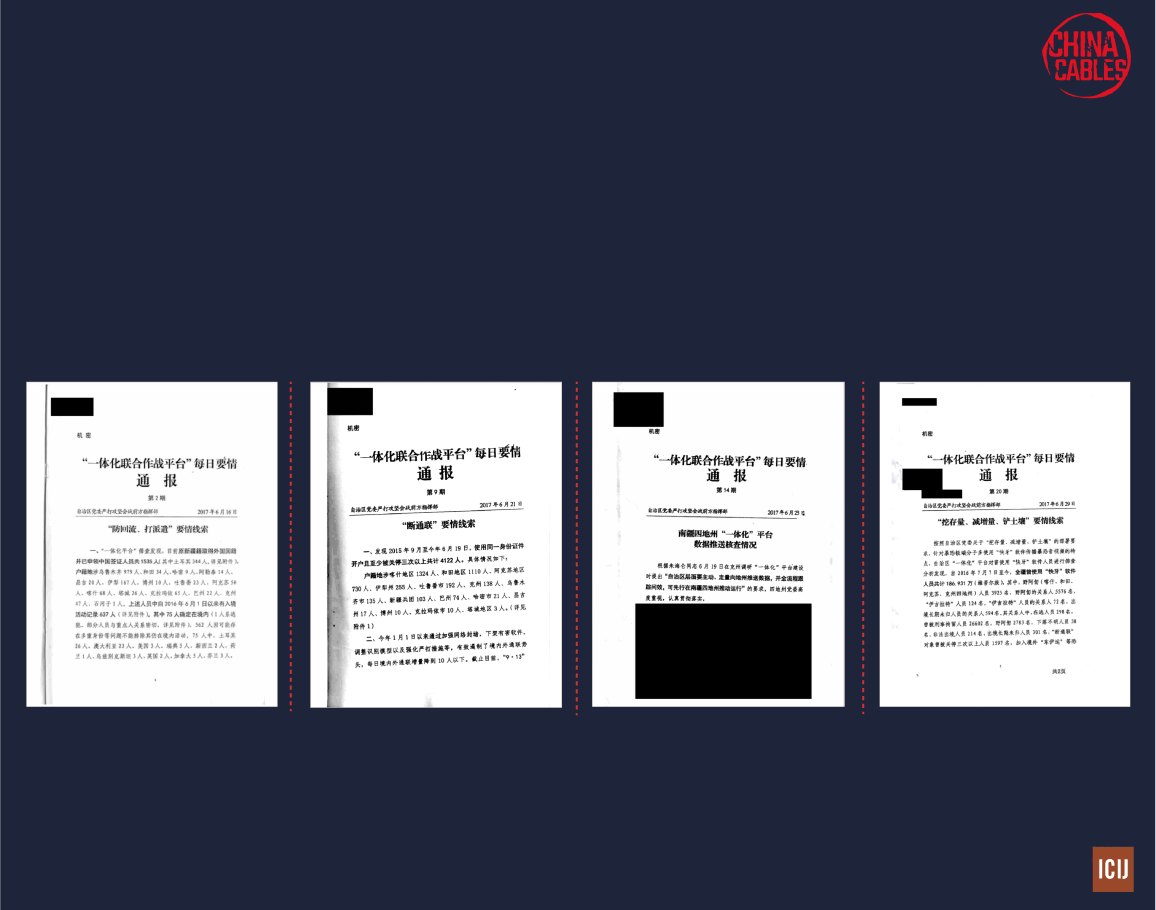

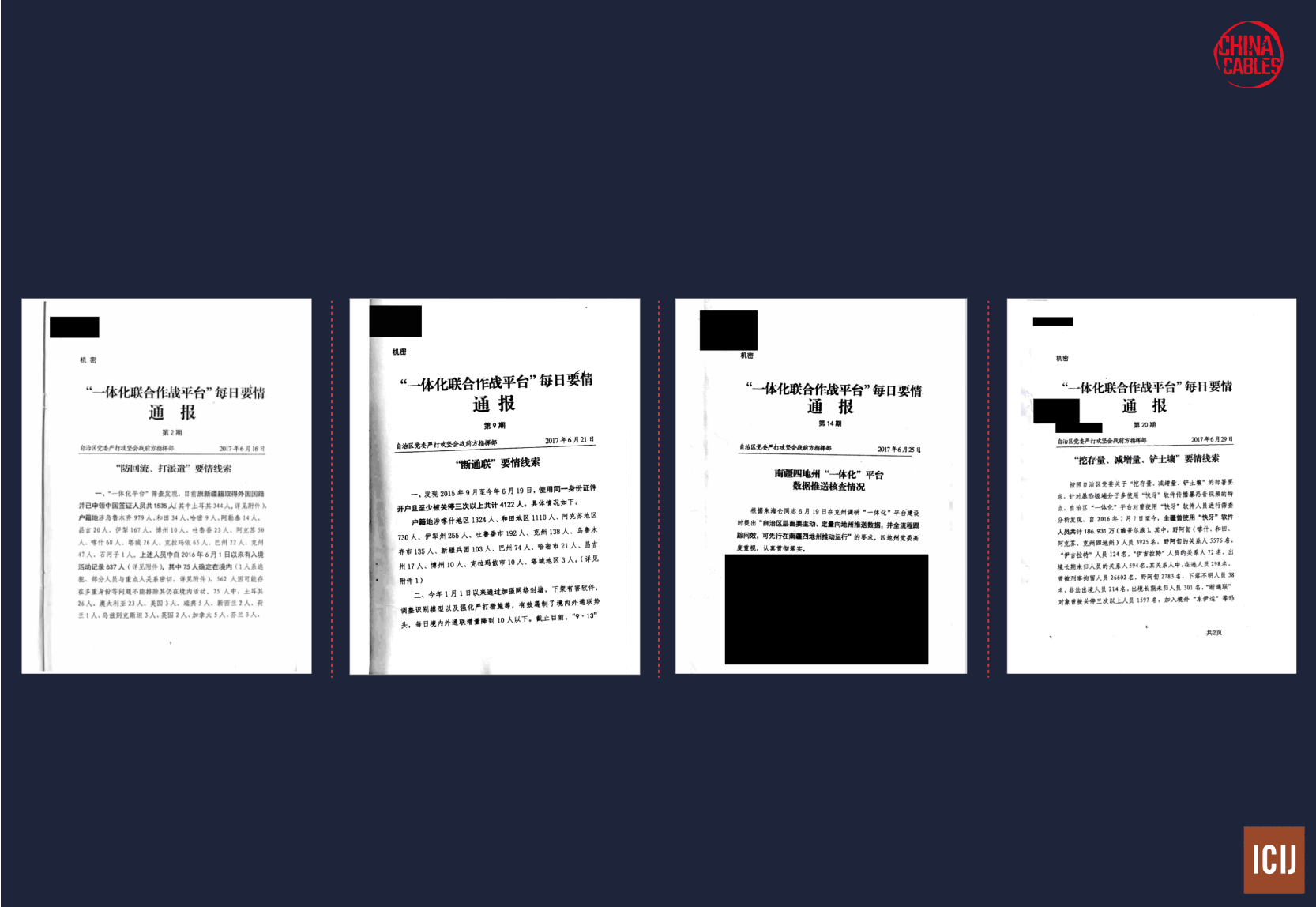

Four “bulletins”

These four “bulletins,” written in Chinese, are secret government intelligence briefings from the Integrated Joint Operation Platform, a centralized data collection system. The bulletins – for the first time – lay out the connection between mass surveillance and the Xinjiang camps.

Bulletin #2

Bulletin #9

Bulletin #14

Bulletin #20

Four “bulletins”

These four “bulletins,” written in Chinese, are secret government intelligence briefings from the Integrated Joint Operation Platform, a centralized data collection system. The bulletins – for the first time – lay out the connection between mass surveillance and the Xinjiang camps.

Bulletin #2

Bulletin #9

Bulletin #14

Bulletin #20

Four “bulletins”

These four “bulletins,” written in Chinese, are secret government intelligence briefings from the Integrated Joint Operation Platform, a centralized data collection system. The bulletins – for the first time – lay out the connection between mass surveillance and the Xinjiang camps.

Bulletin #2

Bulletin #9

Bulletin #14

Bulletin #20

Four “bulletins”

These four “bulletins,” written in Chinese, are secret government intelligence briefings from the Integrated Joint Operation Platform, a centralized data collection system. The bulletins – for the first time – lay out the connection between mass surveillance and the Xinjiang camps.

Bulletin #2

Bulletin #9

Bulletin #14

Bulletin #20

Detention by algorithm

The shorter “bulletins,” meanwhile, provide a chilling look inside the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP), which collects vast amounts of personal information on citizens from a range of sources, and then uses artificial intelligence to formulate lengthy lists of so-called suspicious persons based on this data.

According to Human Rights Watch, the New York-based rights group, the sources include Xinjiang’s countless checkpoints, closed-circuit cameras with facial recognition, spyware that the police require some Uighurs to install in their phones, “Wi-Fi sniffers” that collect identifying information of smartphones and computers, and even package deliveries. Police and other authorities use a mobile app to run background checks and communicate with IJOP in real time, Human Rights Watch says.

“The Chinese have bought into a model of policing where they believe that through the collection of large-scale data run through artificial intelligence and machine learning that they can, in fact, predict ahead of time where possible incidents might take place, as well as identify possible populations that have the propensity to engage in anti-state anti-regime action,” said Mulvenon, the SOS International document expert and director of intelligence integration. “And then they are preemptively going after those people using that data.”

Mulvenon said IJOP is more than a “pre-crime” platform, but a “machine-learning, artificial intelligence, command and control” platform that substitutes artificial intelligence for human judgment. He described it as a “cybernetic brain” central to China’s most advanced police and military strategies.

That’s how state terror works. Part of the fear that this instills is that you don’t know when you’re not OK. – Samantha Hoffman

Such a system “infantilizes” those tasked with implementing it, said Mulvenon, creating the conditions for policies that could spin out of control with catastrophic results.

The program collects and interprets data without regard to privacy, and flags ordinary people for investigation based on seemingly innocuous criteria, such as daily prayer, travel abroad, or frequently using the back door of their home.

Perhaps even more significant than the actual data collected are the grinding psychological effects of living under such a system. With batteries of facial-recognition cameras on street corners, endless checkpoints and webs of informants, IJOP generates a sense of an omniscient, omnipresent state that can peer into the most intimate aspects of daily life. As neighbors disappear based on the workings of unknown algorithms, Xinjiang lives in a perpetual state of terror.

The seeming randomness of investigations resulting from IJOP isn’t a bug but a feature, said Samantha Hoffman, an analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute whose research focuses on China’s use of data collection for social control.

“That’s how state terror works,” Hoffman said. “Part of the fear that this instills is that you don’t know when you’re not OK.”

The four China Cables bulletins obtained by ICIJ, totaling 11 pages, focus on the details of IJOP’s implementation, discussing problems and offering possible solutions. Dated June 2017, they are titled, “ ‘Integrated Joint Operations Platform’ Daily Essentials Bulletin” and comprise issues No. 2, 9, 14 and 20.

“Bulletin No. 14,” for instance, provides instruction on how to conduct mass investigations and detentions after IJOP has generated a lengthy list of suspects. It notes that in a seven-day period in June 2017, security officials rounded up 15,683 Xinjiang residents flagged by IJOP and placed them in internment camps (in addition to 706 formally arrested).

The bulletin goes on to note that IJOP had actually produced 24,412 names of “suspicious persons” that week and discusses the reasons for the discrepancy: Some couldn’t be located, others had died but their ID cards were being used by third parties, and so on. The bulletin notes that some students and government officials were “difficult to handle.”

Last year, Human Rights Watch obtained a copy of the IJOP mobile app and reverse-engineered it to learn how it is used by police and what data it collects. The group found that the app prompts police officers to enter detailed information about everyone they interrogate: height, blood type, license plate, education level, profession, recent travel, household electric-meter readings and much more. IJOP then uses an as-yet-unknown algorithm to create lists of people deemed suspicious.

Maya Wang, senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch, said IJOP’s purpose extends far beyond identifying candidates for detention. Its purpose is to screen an entire population for behavior and beliefs that the government views with suspicion, including signs of strong attachment to the Muslim faith or Uighur identity. “It’s a background check mechanism, with the possibility of monitoring people everywhere,” Wang said.

Dragnet extends abroad

For two years, news organizations have provided increasingly alarming accounts of China’s efforts to shut down Uighur travel and target Uighurs abroad. In November 2016, news organizations reported that officials were confiscating the passports of Xinjiang’s Muslim residents. In July 2017, at China’s request, Egypt deported at least 12 Uighur students studying at Al-Azhar University, a well-known institution for religious studies, and detained dozens more. In early 2018, Uighurs living abroad reported that security bureaus in Xinjiang were systematically collecting detailed personal information about them from relatives still living there.

“Bulletin No. 2” reveals that such acts were part of a broad policy initiative. Dated June 16, 2017, the two-and-a-half page bulletin deals with foreign citizenship and Uighurs who have spent time abroad. It categorizes Chinese Uighurs living abroad by their home regions within Xinjiang and instructs officials to collect personal information about them. The purpose of this effort, the bulletin says, is to identify “those still outside the country for whom suspected terrorism cannot be ruled out.” It declares that such people “should be placed into concentrated education and training” immediately upon their return to China.

The bulletin instructs officials to arrange to deport anyone who has given up, or “canceled,” Chinese citizenship. “For those who haven’t canceled their citizenship yet and for whom suspected terrorism cannot be ruled out, they should first be placed in concentrated training and education and examined,” the bulletin adds.

“Bulletin No. 20” directs local security officials to screen all Xinjiang-based users of mobile phone app Zapya — almost 2 million people — for affiliations with the Islamic State and other terrorist organizations.

Throughout the China Cables, the threat of “terrorism” and “extremism” is cited as grounds for detention, but nowhere in the leaked documents is “terrorism” or “extremism” defined. News reports have indicated that detentions have at times targeted intellectuals, Uighurs with ties abroad and the overtly religious. Yet many others outside these categories have also been swept up. Experts say the campaign is targeting not just specific behavior but also an entire ethnic and religious group.

Ominously, Bulletin No. 2 points to the role of China’s embassies and consulates in collecting information for IJOP, which is then used to generate names for investigation and detention. It cites an IJOP-generated list of 4,341 people found to have applied for visas and other documents at Chinese consulates or who applied for “replacements of valid identification at our Chinese embassies or consulates abroad.” The bulletin includes instructions for those people to be investigated and arrested “the moment they cross the border” back into China.

News organizations have already reported that camp inmate populations included some foreign nationals. Now Bulletin No. 2 shows that their presence in the camps was not accidental but rather an explicit policy objective.

Bulletin No. 2 mentions an IJOP-generated list of 1,535 people from Xinjiang “who obtained foreign nationality and also applied for Chinese visas.” IJOP provided a remarkable level of detail. It determined that 75 were in China, and broke them down by their citizenship: “26 are Turkish, 23 are Australian, 3 are American, 5 are Swedish, 2 from New Zealand, 1 from the Netherlands, 3 from Uzbekistan, 2 from the United Kingdom, 5 are Canadian, 3 are Finnish, 1 is French, and 1 is from Kyrgyzstan.” The bulletin directed officials to find and investigate as many of them as possible, without apparent concern for any diplomatic fallout that might result from placing foreign citizens in extrajudicial internment camps.

‘Extreme thoughts’: Praying and opposing pornography

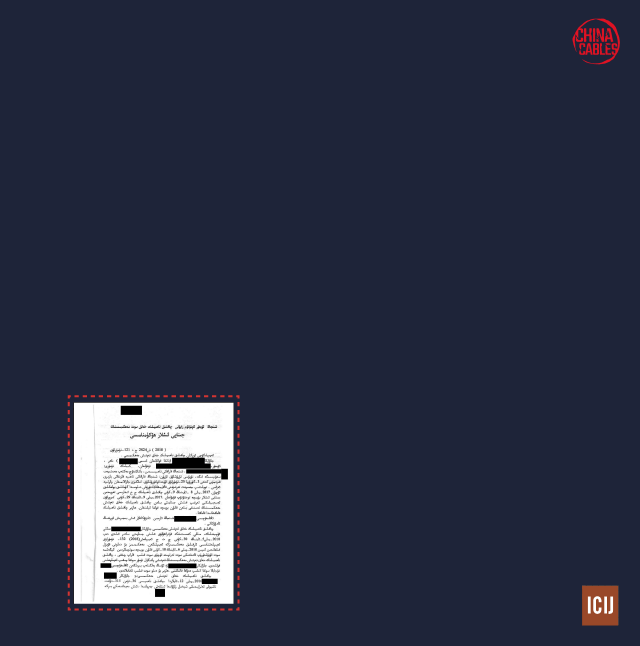

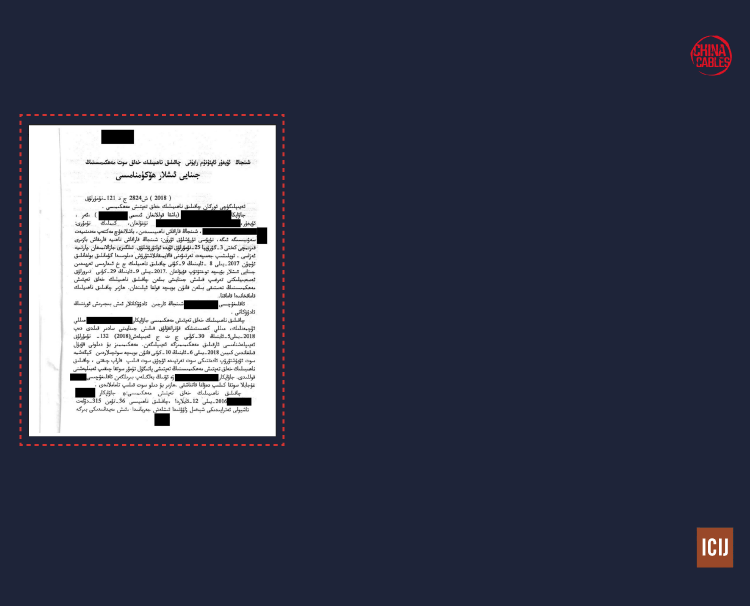

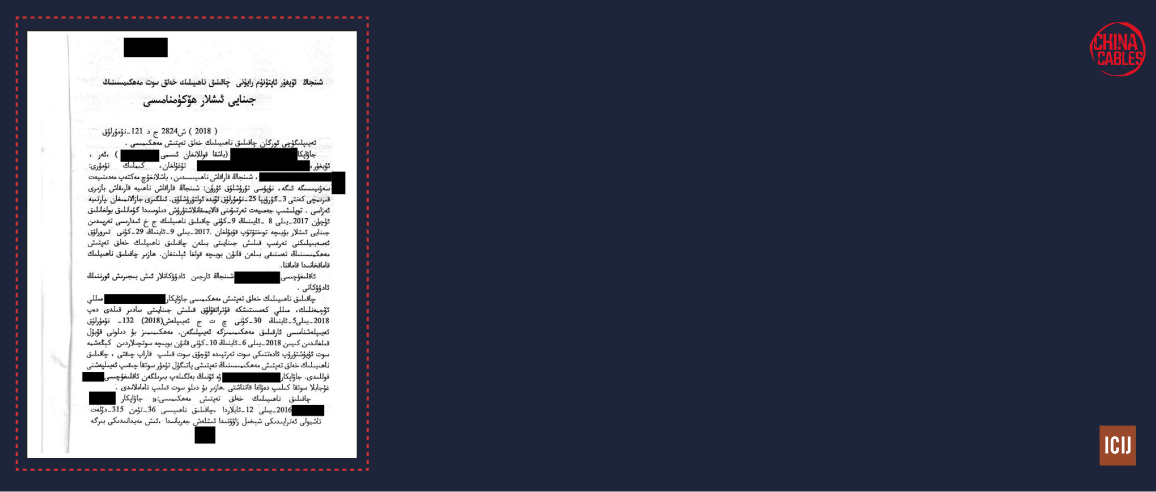

The final document — not classified but of a sort rarely seen outside Chinese government circles — is from a 2018 court case in the Qakilik County People’s Procuratorate in southern Xinjiang. It details, in the Uighur language, allegations against a Uighur man detained in August 2017 and formally arrested the next month on a charge of “inciting extreme thoughts.” Eight months later, he received an additional charge of “incitement of ethnic hatred and ethnic discrimination.”

Court Document

This sentencing document is from a regional criminal court and describes the sentencing of a Uighur man to 10 years for such ideological “crimes” as telling co-workers “not to say dirty words” or watch pornography — lest they would become “non-believers.” It is written in the Uighur language and is not classified, but is a type of document rarely seen.

Court Document

This sentencing document is from a regional criminal court and describes the sentencing of a Uighur man to 10 years for such ideological “crimes” as telling co-workers “not to say dirty words” or watch pornography — lest they would become “non-believers.” It is written in the Uighur language and is not classified, but is a type of document rarely seen.

Court Document

This sentencing document is from a regional criminal court and describes the sentencing of a Uighur man to 10 years for such ideological “crimes” as telling co-workers “not to say dirty words” or watch pornography — lest they would become “non-believers.” It is written in the Uighur language and is not classified, but is a type of document rarely seen.

Court Document

This sentencing document is from a regional criminal court and describes the sentencing of a Uighur man to 10 years for such ideological “crimes” as telling co-workers “not to say dirty words” or watch pornography — lest they would become “non-believers.” It is written in the Uighur language and is not classified, but is a type of document rarely seen.

The case provides a glimpse into how China’s court system has criminalized routine expressions of Islamic belief.

Among the acts deemed unlawful were the man’s urging of co-workers to avoid pornography, to pray and to avoid socializing with those who don’t pray, including “Han Chinese kafirs” (kafir is an Arabic word meaning infidel or nonbeliever). The witnesses to the alleged offenses were co-workers, with Uighur names, with whom he had spoken.

The court document indicates the defendant’s lawyer asked the court for leniency, stating that this was the man’s first offense and that because of his “low legal awareness and education level, he was easily susceptible to being misguided and committing crimes.”

He was sentenced to 10 years in prison.