The United Nations’ human rights office has accused China of committing serious human rights violations against Muslim minorities in Xinjiang that “may” amount to crimes against humanity.

“The extent of arbitrary and discriminatory detention of members of Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim groups … may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity,” the long-awaited report by the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights says.

China had urged the U.N. to not release the report, describing it as a “farce” promoted by Western powers to smear its reputation. The report accuses Beijing of using vaguely worded national security laws to crack down on minority rights. More than a million Uyghurs and members of other Turkic minorities have been detained in Xinjiang camps as part of a forced-assimilation policy, according to human rights groups.

The United States and other Western governments have referred to China’s repression of Muslim minorities in Xinjiang as a form of “genocide.”

The U.N. agency, which had delayed releasing the report for months, concluded that allegations of torture and sexual violence suffered by detainees inside the camps were “credible,” and urged the Chinese government to investigate the abuses and release all those kept in arbitrary detention.

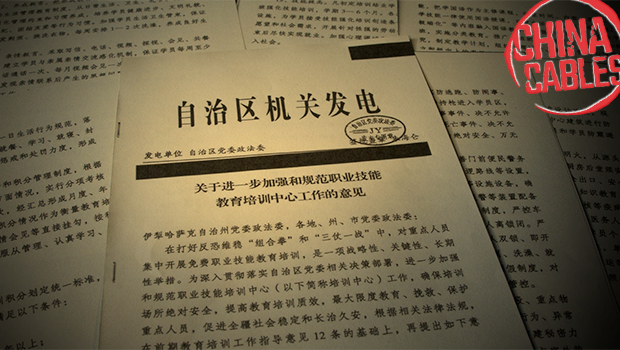

The assessment is based on the agency’s analysis of available judicial data and other records, reports by news media and international researchers, satellite images, China’s official statements and first-hand accounts by former detainees and family members of Uyghurs and other minorities imprisoned for alleged terrorism and other offenses. It cites the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ 2019 China Cables investigation, based on leaked government documents that included the operations manual for running the detention camps in the Xinjiang region and exposed the mechanics of the region’s system of mass surveillance.

Speaking on behalf of 60 Uyghur organizations, the Munich-based World Uyghur Congress, released a statement welcoming the U.N. findings and calling for concrete action by the international community to end human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

“This UN report is extremely important. It paves the way for meaningful and tangible action by member states, UN bodies, and the business community,” said Dolkun Isa, president of the organization of Uyghers in exile. “Accountability starts now.”

China, which has defended its mass detention of Muslim minorities in Xinjiang as a skills training and a counter-terrorism initiative designed to thwart violence and ideological infiltration by religous extremists and separatists, condemned the U.N. findings.

“The assessment is a patchwork of false information that serves as political tools for the U.S. and other Western countries to strategically use Xinjiang to contain China,” Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin said at a press conference today. “It again shows that the U.N. Human Rights Office has been reduced to an enforcer and accomplice of the U.S. and other Western countries.”

‘Patterns of torture’

Reporting by ICIJ, international watchdogs and prominent scholars had previously documented the mass detention program in China’s Northwestern region. Witnesses also told of widespread torture, rape and forced sterilization, forced labor and destruction of Muslim cultural and religious sites in Xinjiang.

Earlier this year, ICIJ and 14 other news organizations published the Xinjiang Police Files investigation based on a leak of records from the public security bureaus of two Xinjiang counties and obtained by German scholar Adrian Zenz.

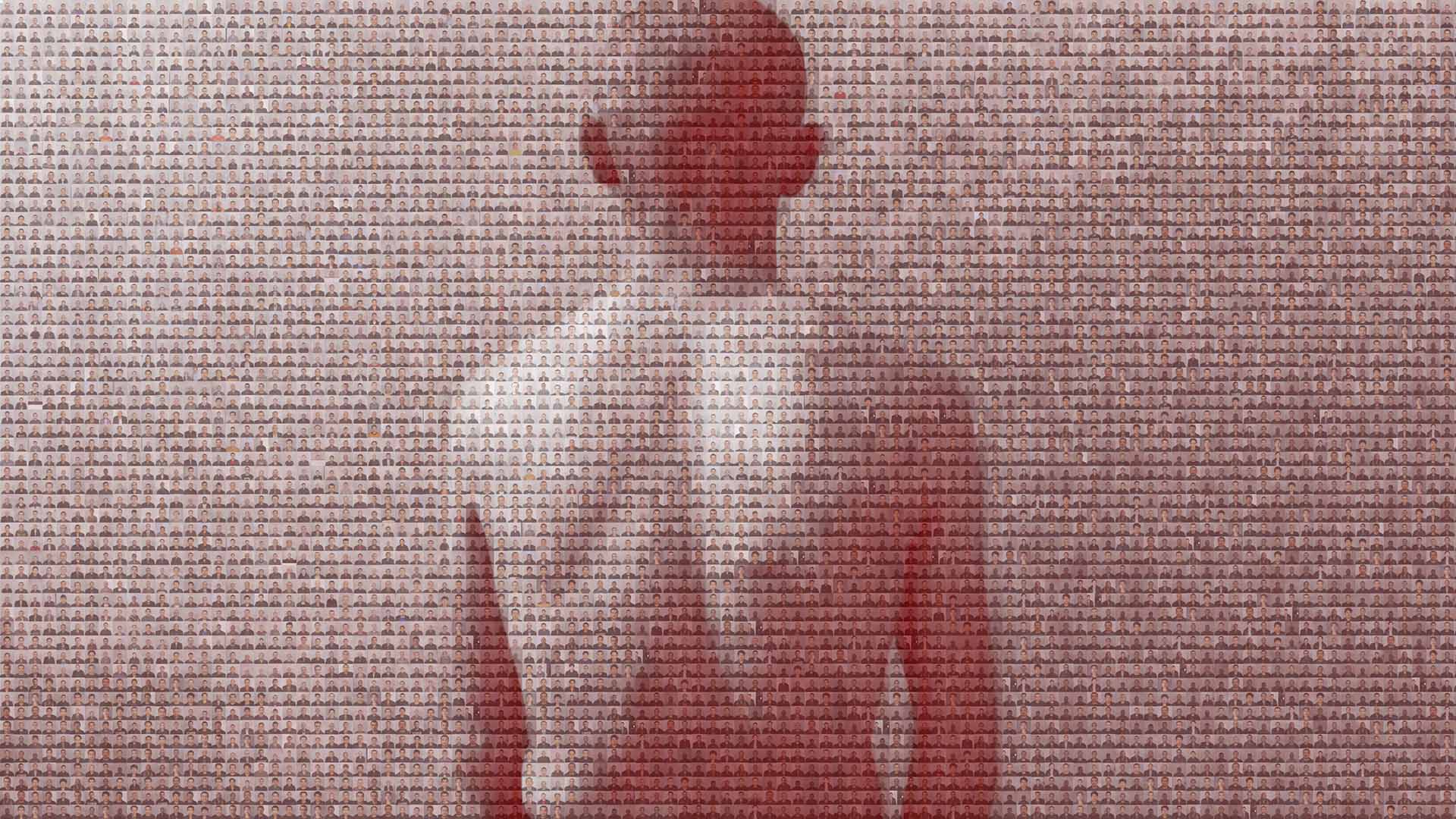

The trove contained confidential government documents, including speeches by high-ranking Chinese officials and more than 5,000 photographs including the mugshots of about 2,900 Uyghur detainees. The photographs of dazed children, men, women and elderlies staring blankly at the camera, in addition to images of drills of police in full riot gear, provided irrefutable evidence of the highly militarized nature of the camps and presented a stark contrast with previously published images that were taken on government-organized press tours.

The U.N. agency’s fresh examination, based in part upon in-depth interviews with 26 former detainees, confirmed many elements of ICIJ’s investigations.

The U.N. report says two-thirds of the former detainees “reported having been subjected to treatment that would amount to torture and/or other forms of ill-treatment” either in captivity or in the process of being referred to the detention centers.

Former detainees interviewed by U.N. investigators also said they were administered medicines that made them “feel drowsy,” and suffered hunger and severe health effects due to the living conditions in the centers.

Based on those accounts the report identified “patterns of torture or other forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, other violations of the right of persons deprived of their liberty to be treated humanely and with dignity.”

The report was released just as High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet is leaving office after a tenure marked by controversy. Human rights groups had accused her of not taking a tough enough stance on China over the persecution of Muslim minorities and having avoided hard questions durign a visit to Xinjiang last May.

At a news conference last week, Bachelet told reporters that her office was “under tremendous pressure” and that she had received a letter signed by countries including North Korea, Venezuela and Cuba “asking for the non-publication” of the report.

China has long defended the program as part of its anti-terrorism policy. However, U.N. analysts found that the policy “is based on vague and broad concepts,” after examining a sample of available judicial decisions in cases alleging terrorism or “extremism” against defendants from ethnic communities in Xinjiang from 2014 to 2019.

The agency’s analysis found “relatively minor infractions apparently punished severely,” and that “judgments referring to conduct being ‘extremist’ despite none of the formal charges being related to terrorism or ‘extremism.’”

The report acknowledges limitations such as the lack of data on sentencing and convictions and the availability of official statistics only until 2019. The Chinese government has not provided data for 2020 and beyond, the report says.