Guo Jian took notes as Khenpo Sonam Tenphel, speaker for the Tibetan parliament-in-exile, met with pro-democracy activists in 2017 in Dharamshala, India, and discussed China’s repressive policies against the Tibetan minority.

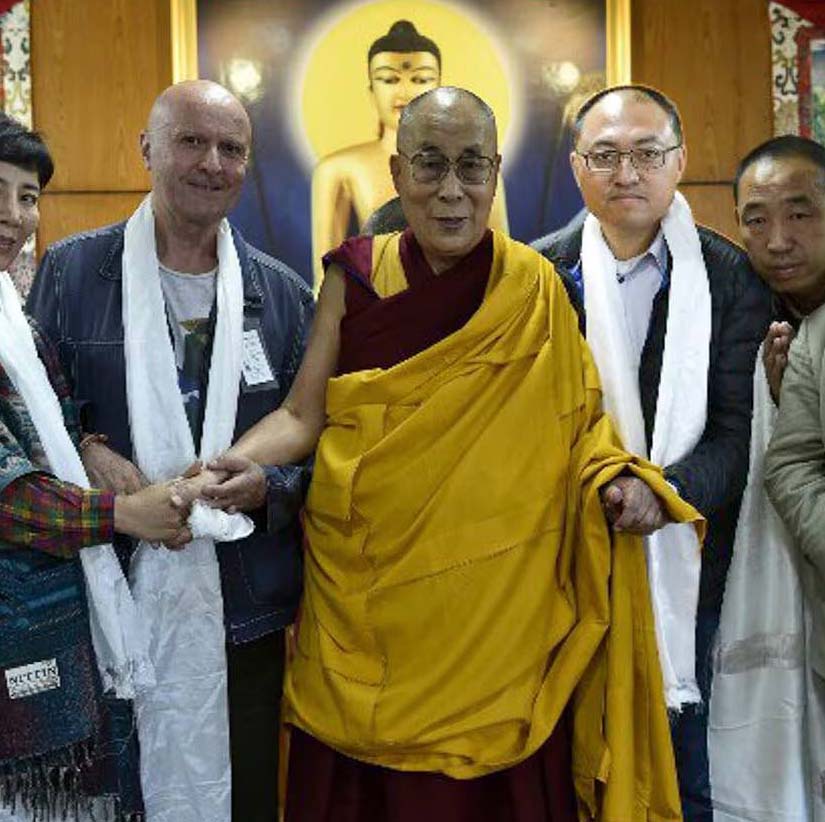

A naturalized German, Guo, then 36, wearing glasses and a traditional white khata scarf, his hair in a buzz cut, was part of a delegation of Chinese democracy advocates from Europe.

Over a few days, Guo met and took photos with the leader of a Tibetan women’s association, the Tibetan parliamentarian and even the Dalai Lama, who’s considered a spiritual leader by Buddhists worldwide and a “separatist” by the Chinese government.

Tibetan media celebrated the activists as “Chinese supporters of the Tibet campaign.” But in the weeks following Guo’s return to Germany, where he lived, some Chinese dissidents who often organized pro-democracy events with him began to grow suspicious about his behavior.

Chinese dissidents overseas typically take precautions to protect their identities from potential government surveillance. They often use nicknames, don’t share private information with strangers, and communicate only through secure, encrypted channels.

Guo began to break these unspoken rules. He became unusually deferential toward some of the activists in his circle, insisting on visiting them at their private residences, Tienchi Martin-Liao, a human rights advocate from Taiwan, told the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Guo also inquired about the Dalai Lama’s health and details of the spiritual leader’s upcoming trips to Europe, said Martin-Liao, who, like Guo, is part of the Federation for a Democratic China and was in contact with Tibetan government representatives. “So we [became] a little bit alert,” she said.

Despite uncertainties about Guo’s motives, the members of the group appointed him secretary general, as the group’s older generation of activists hoped he would join its leadership one day, Martin-Liao said. Described by the more senior activists as “low key” and “quiet,” and as “aggressive” and “confident” by younger ones, Guo helped during their conferences, taking care of the logistics, picking up international guests at the airport and buying food for the event participants.

“We wanted him to belong to the core [of the organization] but, after a certain time, we noticed that his behavior was not quite right,” Martin-Liao said.

They weren’t the only ones with doubts. In 2023, when Guo tried to persuade younger activists to help him organize pro-democracy events, he insisted on knowing their real names, increasing their suspicions about him, sources familiar with the events told ICIJ.

Their fears materialized last year when German authorities arrested Guo, accusing him of being a Chinese government spy since 2002.

Unbeknownst to Martin-Liao and other activists, months after the trip to Dharamshala, Guo had accompanied far-right German politician Maximilian Krah to China, German media reported, and later became an aide to the member of the European Parliament in Brussels.

Guo, who denied wrongdoing, told the German news website t-online, that, “as a native Chinese” he cares about “German-Chinese friendship.” ICIJ’s attempts to contact Guo through email and phone were unsuccessful.

In the aftermath of Guo’s arrest last year, Krah said in a statement on social media that he was not aware of the aide’s alleged links to the Chinese intelligence services. He has also denied wrongdoing.

As part of the ongoing case, German federal prosecutors allege that Guo leaked more than 500 documents, including classified files on European Parliament proceedings, to China’s intelligence services for years and gathered information on political figures and dissidents in 2023 and 2024. Belgian authorities said they are also investigating the matter.

Guo is one of many Chinese nationals to be accused by Western authorities of working for China’s spy agencies and infiltrating anti-Communist Party groups around the world. Authorities in the U.S, Canada and other democratic nations have also accused former law enforcement officers and private investigators from those countries of actively collaborating with the alleged spies and enabling their surveillance and intimidation efforts.

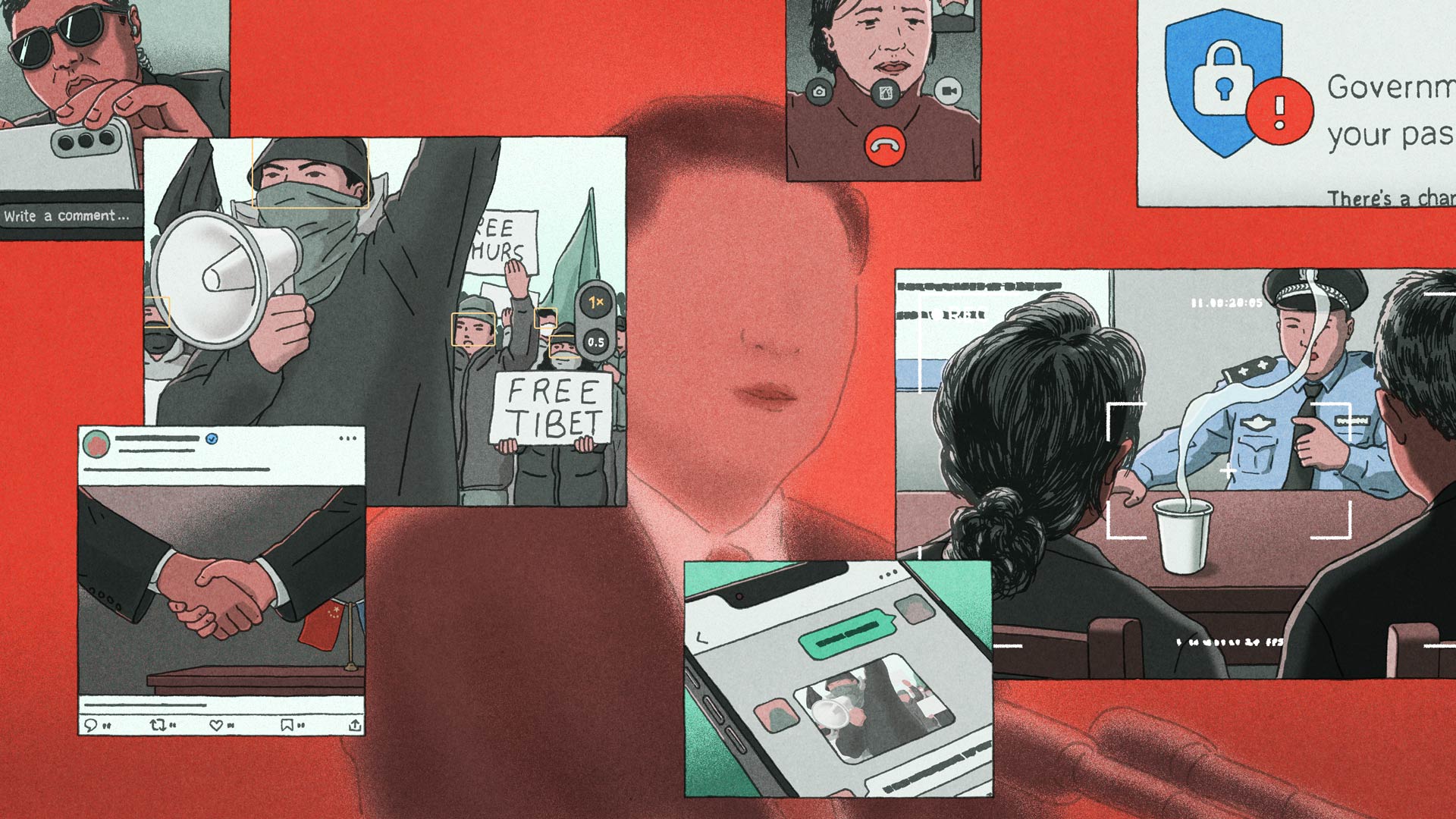

The findings are part of China Targets, an ICIJ investigation in collaboration with 42 media partners, which details Chinese authorities’ tactics to monitor, intimidate and threaten political opponents and the failure of inter-governmental institutions in countering state-sponsored repression.

ICIJ and its partners found that Beijing’s strategy to silence regime critics also relies on right-wing social media groups in foreign countries, professional hackers, staff of Chinese nongovernmental organizations with access to United Nations proceedings and members of China’s diaspora connected to the CCP-linked United Front Work Department.

The alleged use of civilians like Guo, the activist and businessman-turned-political aide, is yet another tool in the Chinese government repression playbook, experts say.

It also shows the “tremendous” extent of China’s repression efforts, according to Nicholas Eftimiades, a retired U.S. intelligence officer and author of the book “Chinese Espionage Operations and Tactics.”

“They’re reaching out globally in every way to try and destroy opposition, and intelligence is one of them,” Eftimiades said.

At a news conference in Beijing last year, a spokesman for China’s Foreign Ministry, Wang Wenbin, dismissed the espionage allegations against Guo as “media hype” intended to smear China. “The so-called ‘threat of Chinese spies’ is not a new thing in Europe,” Wang said. “Let me stress that China carries out cooperation with European and all other countries on the basis of mutual respect and non-interference in each other’s internal affairs.”

German prosecutors declined to answer ICIJ’s questions and clarify why they accused Guo of spying on Chinese pro-democracy advocates only during the year prior to his arrest. ICIJ has examined websites of groups he was involved with and spoken to several activists who organized pro-democracy events with him as well as others who met him briefly. They confirmed that his involvement with critics of the Chinese Communist Party goes back more than a decade.

Now, dissidents who attended conferences Guo helped organize fear that he may have used those events to gather participants’ private details and pass them to Chinese authorities.

“I worried about this, because when you do preparations for a conference you have everyone’s information,” said a Canada-based activist who goes by the name Sheng Xue, who met Guo at several events. “He was very careful, very quiet, very alert. During conferences he stayed on the side, looking at people.”

Martin-Liao, the activist who participated in events alongside Guo, said that while his behavior was alarming, they had no evidence that he could be a secret agent.

“We know that some people are really suspicious,” and could be working for the Chinese government to “find out what happens, who is who and so on,” Martin-Liao said. “But we are just normal people, we are not police or security [officers].”

“If somebody is collecting information for the Chinese government, they join our conference and get all the information, who was there, who is the main host,” she said. “The Chinese government wants to know everything.”

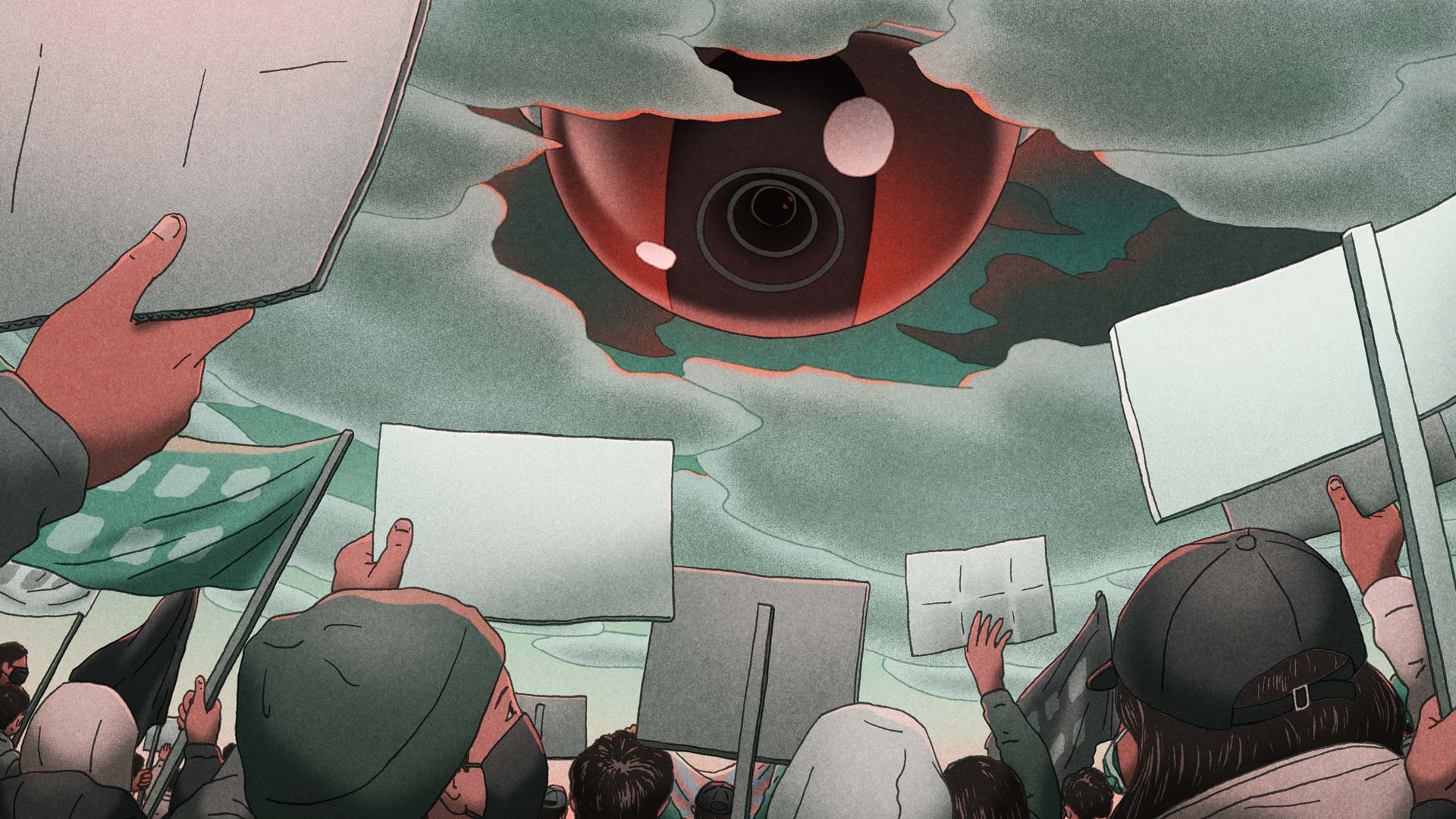

Several governments, including the U.S., New Zealand, Sweden, Turkey and Australia, have investigated dozens of suspects allegedly involved in Chinese covert operations targeting dissidents in recent years. In some cases authorities found that the targets of espionage later ended up in prison or had family members threatened.

Last week, the leaders of the Group of Seven meeting in Kananaskis, Canada, issued a joint statement condemning transnational repression “as an important vector of foreign interference” and pledged to boost cooperation to protect their sovereignty and the targeted communities.

“It has real life consequences,” Eftimiades said. “China is effective in destroying opposition, simply because they inspire that type of fear and distrust within those communities.”

Work for us or ‘we’ll destroy you’

The Chinese government has also turned victims into perpetrators.

Shadeke Maimaitiazezi, a 60-year-old textile trader from Kargılık, Xinjiang, is currently sitting in an isolation cell in Istanbul, where he was recently convicted of spying on fellow Uyghurs on behalf of the Chinese state. He has denied the allegations and accused Turkish authorities of forcing him to give a statement under duress, his lawyer Fatih Davut Ejder told ICIJ’s media partner Deutsche Welle Turkey.

Maimaitiazezi, a Muslim, has five children, including three who still live in Xinjiang, the Chinese province where many Uyghurs live and where Beijing has implemented mass-detention and other repressive policies targeting the local minority which may constitute “crimes against humanity,” according to the United Nations.

Maimaitiazezi moved to Turkey in 2017 after losing his business due to the worsening trade relationship between the two countries. He claimed he became involved with Chinese agents years later, when an officer from his hometown forced him to become a spy by threatening his family.

Maimaitiazezi told Turkish investigators that the officer said, “you have relatives and loved ones here,” according to interrogation records reviewed by ICIJ. “He threatened and frightened me by telling me to think about their fate,” Maimaitiazezi told Turkish investigators.

In early 2023, Maimaitiazezi flew to Hong Kong to meet the officer but he was detained for 15 days, he said. When the officer and a colleague showed up, he said, they had a deal for the Uyghur trader: “China is a very big country, and if you work for us you will be saved,” they allegedly told Maimaitiazezi. “Otherwise we will destroy you and everyone you love.”

Maimaitiazezi claimed that the two Chinese officers then told him there was an international arrest warrant against him, but it could be voided if he returned to Turkey to spy on dissidents involved in activities related to East Turkistan, the name Uyghurs use for Xinjiang. According to the indictment, in the following months, they allegedly paid him more than $100,000 through intermediaries to provide information on activists. One of the alleged surveillance targets was Abdulkadir Yapchan, a Uyghur rights advocate who’s wanted by China on terrorism charges — allegations that a Turkish court has dismissed as politically motivated. The officers also asked Maimaitiazezi to find information on Uyghurs who had joined terrorist groups in Syria; he didn’t find any, he said.

In his defense, his lawyer Ejder said the evidence against Maimaitiazezi is thin. He did not have any secret information on political dissidents because he was not one of them, Ejder said, adding that the only information Maimaitiazezi gave Chinese officers is publicly available on Facebook and media reports.

Maimaitiazezi’s alleged target, Yapchan, also dismissed the alleged spying attempt. “Everyone is threatened by China,” Yapchan told ICIJ.

A Turkish court recently sentenced Maimaitiazezi to 12 years and six months in prison. He is appealing the verdict. In the meantime, the long isolation and harsh prison conditions are weighing on Maimaitiazezi, his lawyer said. “Psychologically, he is now very worn out.”

According to Haiyuer Kuerban, a Berlin-based advocate with the World Uyghur Congress, cases like that of Maimaitiazezi are part of Beijing’s “massive and strategic” approach to infiltrate Uyghur communities and quash dissent outside China.

“It’s unrealistic that a few diplomatic staff can control China’s vast diaspora,” Kuerban told ICIJ. “A fire is burning outside China, and they are using every possible means to put it out.”

An internal government document obtained by Abduweli Ayup, a former political prisoner and Norway-based advocate who documents human rights abuses against Uyghurs, shows that the use of civilians and community leaders to provide information to the authorities has been a common practice in Xinjiang for years.

The document, a “registration form for public security informants,” lists three types of informants: individuals who voluntarily provide information, those who gather information covertly and others who work under the direction of a police officer or security bureau staff member.

Confidential domestic security guidelines reviewed by ICIJ as part of China Targets also revealed that the use of what Chinese authorities called the “covert struggle” is part of security officers’ strategy to control and stop any individuals deemed a threat to the Chinese Communist Party rule — regardless of whether they are inside or outside China.

Now advocates fear that the government’s use of informants in the Uyghur diaspora has become common overseas.

Swedish authorities recently arrested a Uyghur advocate who worked for the World Uyghur Congress, accusing him of spying on fellow Uyghurs for the Chinese government. The man denied the allegations and was released pending trial; the case is ongoing. It is the second time since 2009 that Swedish prosecutors have brought such charges against a Uyghur refugee.

ICIJ’s reporting partner in Switzerland, Tamedia, also identified a Swiss academic who boasted of contact with Chinese security forces, and asked Uyghurs living in the country to reveal private information, such as their full names and addresses. Sources told Tamedia journalists that they have reported the academic to the Swiss intelligence agency as a potential spy. The academic admitted to the reporters that he does have contacts with members of the security services in China but denied allegations of intelligence gathering. The Swiss agency did not comment on the matter.

From dissident to spy

One summer day in 2008, Eric, then an activist in his early 20s, heard a knock on the door of his Chongqing apartment. Four police officers were there to arrest him for joining the China Social Democracy Party, a U.S.-based political group that opposes the CCP.

They took him to the police station, where they interrogated and threatened him, Eric, who asked not to reveal his real name for security reasons, told ICIJ. The officers later offered him a way out: “They said either work for them, or things could get very serious — which meant that I would have to go to jail,” Eric said in a recent interview. “I was very hesitant, but I agreed. In addition to not wanting to go to jail, because I had nothing to betray.”

Eric yielded to authorities’ pressure and began to use his political activism as a cover for infiltrating dissident groups, working for Chinese police until 2023, when he defected to Australia. Eric revealed part of his story for the first time in an interview with ABC Australia last year. After Xi Jinping became president in 2013, resources for overseas intelligence operations increased, he said, and his handlers sent him to South Asia.

In 2016, Eric said he obtained the praises of senior officers when he managed to infiltrate an event in India with the Dalai Lama and prominent political activists from China and Hong Kong. Years later, he used a temporary stint as a planning supervisor of a Cambodian conglomerate’s subsidiary to hire a famous Chinese political cartoonist and lure him to Southeast Asia where Chinese police planned to arrest him. He also set up a fake anti-CCP militia complete with a YouTube channel with the aim of befriending a Chinese activist who eventually fled to Canada, where he was later found dead. (Canadian authorities said his death was not suspicious.)

Eric used four different communication apps to exchange messages with his China-based handlers and discuss targets’ locations and weak points, as well as surveillance technology, such as a sophisticated laser beam able to secretly intercept conversations, according to confidential messages and documents that Eric shared with ABC Australia and ICIJ.

“The more important the person is, the greater their influence [is], and the more critical of the Communist Party and Xi Jinping they are, the more likely it is that he or she may be included in the entrapment list,” Eric said. “Most of the time, the method is the same: approach the target, establish contact, and deepen trust.”

Eric told ICIJ that even if he worked as a spy, he remained a dissident at heart and didn’t feel bad that his missions often failed. He admits his role in China’s effort to crush dissent worldwide: “My activities overseas can be considered transnational repression,” he said.

To stay in Thailand, Eric obtained a visa in 2019 as a business planning manager for a small company that ran a room-rental business in central Bangkok.

Days after Eric started his job at the company, one of his handlers sent him a message to remind him of his important mission. “Cover work is also very important,” the officer wrote in the message viewed by ICIJ. “It not only plays a role in covering up, but also helps you truly integrate into Thai society.”

The officer continued: “As the saying goes, it takes a thousand days to raise soldiers. You and I have been in the incubation period in the past few years. Now it’s time to work hard.”

Leaving them vulnerable

Guo moved to Germany as a student in 2002. He joined pro-democracy movements while working as a director for a company that traded electrical products and a firm providing “consulting service for intercultural communication between Germany and China,” according to corporate records. Both companies were based in Dresden, where he reportedly met Krah, the Alternative for Germany Party politician and lawyer.

German media reported that Guo approached the country’s foreign intelligence agency in 2007 offering to work as an informant but was turned down. According to the media reports, he later began to cooperate with the domestic security services in the eastern state of Saxony, providing information on Beijing’s activities against regime critics living in Germany. The agency, which never gave him assignments, later dismissed him and he was allegedly put under surveillance on suspicions of being a double agent, the media reports said. In early 2024, authorities arrested Guo after obtaining evidence that he had secretly passed confidential European Parliament information to the Chinese government.

According to Eftimiades, the expert on China’s intelligence activities, it’s not unusual for authorities in democratic nations to take time in developing cases involving Chinese covert operations — and sometimes they can miss the clues altogether until it’s too late.

Eftimiades said he has trained hundreds of police officers and intelligence agents in the U.S. and other countries about the basics of the Chinese security apparatus as well as “operational methodologies of China’s covert influence operations,” including notions of transnational repression and its implications for dissidents overseas.

“The reaction I get consistently from law enforcement and others is [about] the breadth and scale of China’s actions, because they don’t know all these things are happening,” he said. “When you put it in front of them and show them all the cases and the specific acts — that’s the most impactful moment for them.”

ICIJ and its media partners have interviewed 105 people in 23 countries who have been targeted by Chinese authorities in recent years for criticizing the government’s policies publicly and privately. The targets included Chinese and Hong Kong political dissidents as well as members of oppressed Uyghur and Tibetan minorities.

Forty-eight targets of China’s transnational repression said they believe they have been spied on, were asked to spy on others or know of people in their communities who were asked to become informants.

Though studies by the Center for Strategic International Studies, a U.S. think tank, show that reported cases of Chinese espionage are increasing, law enforcement education about Chinese repression tactics is not growing at the same pace, experts said.

Law enforcement responses across [EU] Member States are inconsistent, and specialized victim support is largely missing. — European Parliament lawmaker Hannah Neumann

In Europe, where the case involving Guo has been unfolding, lawmakers interviewed by ICIJ said that authorities’ responses to such threats remain inadequate.

Hannah Neumann, a lawmaker from the Greens party who took over Krah’s office inside the European Parliament building after the elections last year, told German magazine Der Spiegel that she and other parliamentarians had “long wondered about this employee [Guo] who only appeared when it was about Chinese interests.”

As a politician who has called for stronger measures against authoritarian regimes’ reach over their diasporas, Neumann told ICIJ that the European Union “still lacks the tools to address interference by proxy actors operating under civilian cover.”

“Law enforcement responses across Member States are inconsistent,” she said, “and specialized victim support is largely missing.”

Eftimiades said forces in other democratic nations have the same challenges.

“It’s just now we’re starting to pay attention to it,” he said. “If someone comes and says: ‘Hey, I’m being threatened or, you know, so-and-so is working for the Chinese state,’ there’s no guarantee that the government is going to do anything. And that leaves that person in a very vulnerable position.”