On a chilly afternoon in the spring of 2021, while awaiting an extradition hearing in Bordeaux, France, Businessman H. received an unexpected call from an old friend and business partner.

Jack Ma was on the line.

H. was surprised to hear from Ma, the tech titan and one of China’s richest men, according to a transcript of the call.

Ma said he was calling at the behest of Chinese authorities, who were seeking H.’s immediate return to China.

“Did they approach you?” H. asked.

“Mmh,” Ma acknowledged. “They said I’m the only one who can persuade you to return.”

A few weeks earlier, H. had been arrested by French authorities on the basis of a red notice, an alert circulated among police forces worldwide by Interpol, the international police organization that critics say is often misused by authoritarian regimes.

Ma, co-founder of the sprawling Alibaba retail and technology empire, had himself only recently reemerged into public view. He had disappeared for three months after making a scathing speech in which he criticized Chinese financial regulators. As a result, the government abruptly nixed the stock market debut of his Ant Group, a financial technology firm, and forced its restructuring. Ma told H. that top officials at China’s anti-graft agency approached him with a peculiar mission: persuade H. to return voluntarily from France, court records show.

Chinese authorities were trying to get H., a China-born naturalized citizen of Singapore, to testify in a case unrelated to anything in his red notice: a corruption case against a former vice public security minister named Sun Lijun, according to court records obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and its partners Radio France and Le Monde on the condition that H.’s real name not be used.

H. declined to comment for this story; Ma didn’t respond to ICIJ’s requests for comment.

A prominent businessman in his own right, the 48-year-old H. owned a vineyard in Bordeaux in southwestern France and frequently appeared in Chinese tabloids beside his wife, Zhao Wei, a movie star turned business tycoon. Just a month before Ma’s call, French officers had arrested H. as he stepped off a private jet at the Bordeaux airport citing a red notice issued by Interpol against him at the request of Chinese prosecutors in the southern city of Dongguan.

The notice accused H. of money laundering and complicity in an embezzlement scandal involving Tuandai, a private lending company H. had invested in. It made no mention of the high-profile government case against the vice minister, Sun Lijun.

“They’re using the Dongguan case as a pretext,” H. told Ma. “If I explain clearly what happened with Sun Lijun, they won’t pursue me anymore. Is that what they assured you? Right now I don’t believe anyone.”

“I think you don’t have any other choice,” Ma said. “Now they’re giving you a chance. If you don’t come back, they’ll definitely destroy you.”

“… I understand. I’ll think about it,” H. replied, and hung up.

H.’s case is hardly isolated. A decade ago, Chinese President Xi Jinping began publicly calling for stepped-up international law enforcement action to track down what he called corrupt citizens abroad. Since then, a cross-border investigation led by ICIJ found that China has used red notices and other Interpol tools to target not only criminals, but also businesspeople with political connections like H., along with regime critics and members of persecuted religious minority groups seeking refuge overseas.

The case of H. and many others show how, despite attempts at reforming Interpol, the organization’s secretive processes and reluctance to hold system abusers publicly accountable remain a boon for authoritarian regimes. China does not appear to be among countries currently subject to Interpol corrective measures for alleged misuse of the organization’s system, ICIJ and its Slovenian media partner Oštro found.

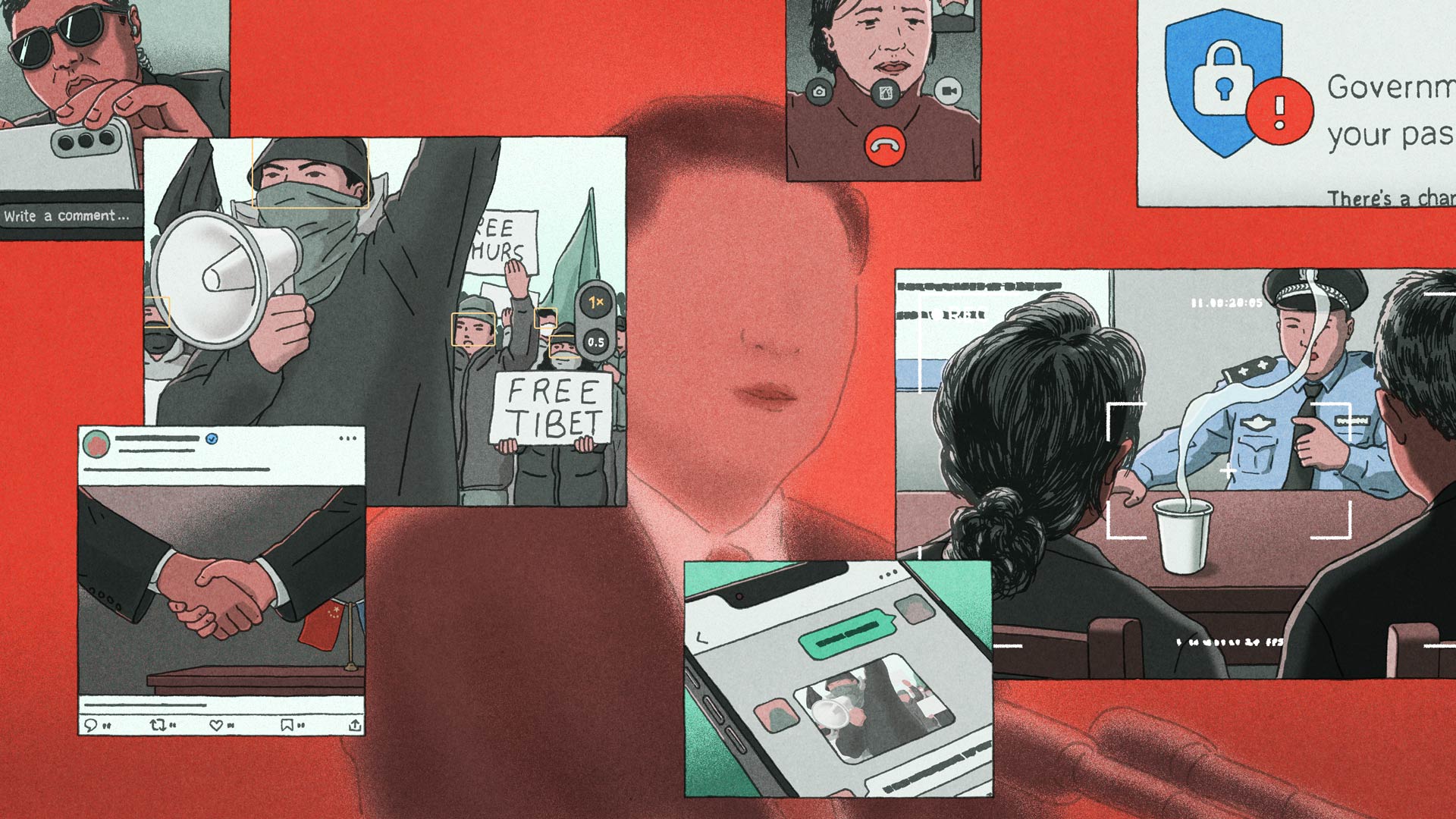

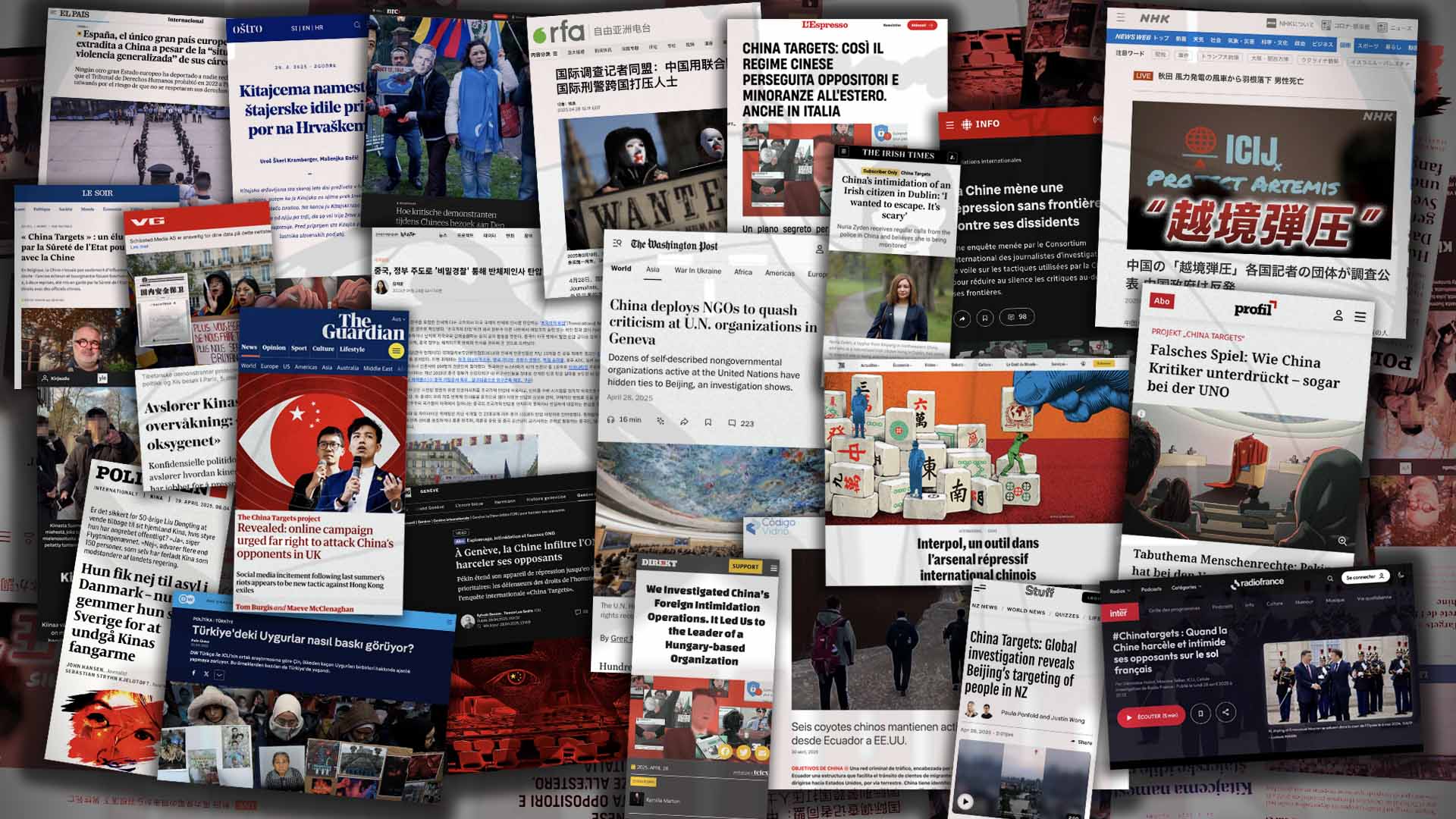

The findings are part of ICIJ’s China Targets investigation, a collaboration of 43 media partners in 30 countries that exposes the mechanics of the Chinese government’s global repression campaign against its perceived enemies and the governments and international organizations that allow it. The investigation found that China’s misuse of Interpol is part of a well-organized effort to silence and coerce anyone that the Chinese Communist Party deems as a threat to its rule, including those no longer on Chinese soil. Chinese authorities also use surveillance, hacking, financial asset seizure and intimidation of targets’ relatives in China and other measures to neutralize regime critics beyond its borders.

The investigation is based on interviews with more than 100 targets of China’s transnational repression who now live in 23 countries, as well as secret video and audio recordings of police interrogations, confidential Chinese documents and other evidence.

Ted Bromund, a strategic studies specialist and expert witness in legal cases involving Interpol procedures, says Interpol has become central to China’s campaign of transnational repression, a vital “tool” to put pressure on targets abroad. In particular, China uses red notices “like a pin through a butterfly,” he said. “It holds someone down, locks them in place so they can’t get away.”

In a statement to ICIJ Liu Pengyu, a spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., said that “the Chinese government strictly abides by international law and the sovereignty of other countries.” Liu did not address specific questions about China’s use of Interpol. China’s Public Security Ministry did not respond to ICIJ’s comment request.

‘We must bring them back’

In November 2014, representatives of international police forces gathered in Monaco to celebrate 100 years since a group of lawyers and police officials from 24 countries first came up with the idea of creating Interpol. The organization, whose mission is to assist local law enforcement agencies around the world and boost police cooperation, now has 196 member countries.

While other high-ranking officials had delivered soaring speeches praising the organization’s accomplishments and urging further cooperation between police forces, Meng Hongwei, then China’s vice public security minister, got on stage with a special message from the Chinese government.

Although the People’s Republic of China did not become an Interpol member until 1984, Meng said Interpol had become an “important channel for the Chinese police to have assistance in investigation and cooperation on cross-boundary cases.”

It was time for member countries to step up their game, he added, and “make the best use of Interpol’s resources” to hunt for terrorists and fugitives worldwide — two categories that critics say China often uses for political opponents and members of the Uyghur ethnic minority.

Xi himself had mentioned “police cooperation” more than once in speeches while traveling to meet world leaders, according to a provincial anti-corruption agency’s website, and made the priority clear to officials at a plenary session of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, China’s anti-graft agency.

“We must not allow foreign countries to become a ‘haven for criminals’ for some corrupt elements,” Xi told the officials, according to a state news agency. “Even if corrupt elements flee to the ends of the Earth, we must bring them back and bring them to justice. We must pursue them for five, 10 or 20 years and cut off the escape routes of corrupt elements.”

The government soon after launched two large-scale anti-corruption campaigns known as Fox Hunt and Sky Net, vowing to go after what it described as corrupt officials who had fled overseas. The Ministry of Public Security set up a special unit in charge of international cooperation and incentivized police bureaus to use Interpol.

China’s bureaucracy was gearing up for a global clampdown.

Provincial records reviewed by ICIJ show how public security bureaus competed to show the central government the number of “cracked” cases — targets of red notices and other suspects intercepted and repatriated.

Chinese local media and websites affiliated with the Communist Party’s Central Committee began to routinely cast Chinese police officials hunting criminals overseas as heroes. One article in a site linked to the party spotlighted an officer in his early 30s, nicknamed “Boss,” who reportedly found the location of a suspect by analyzing pictures posted on the suspect’s social media account and magnifying an image reflected in a cat’s eyes. A piece in a Wuhan newspaper glowingly describes another officer’s methods — “warmly praise the other party, give small gifts, invite them to dinner” — to convince a judge in the Philippines to issue an arrest warrant against a suspect.

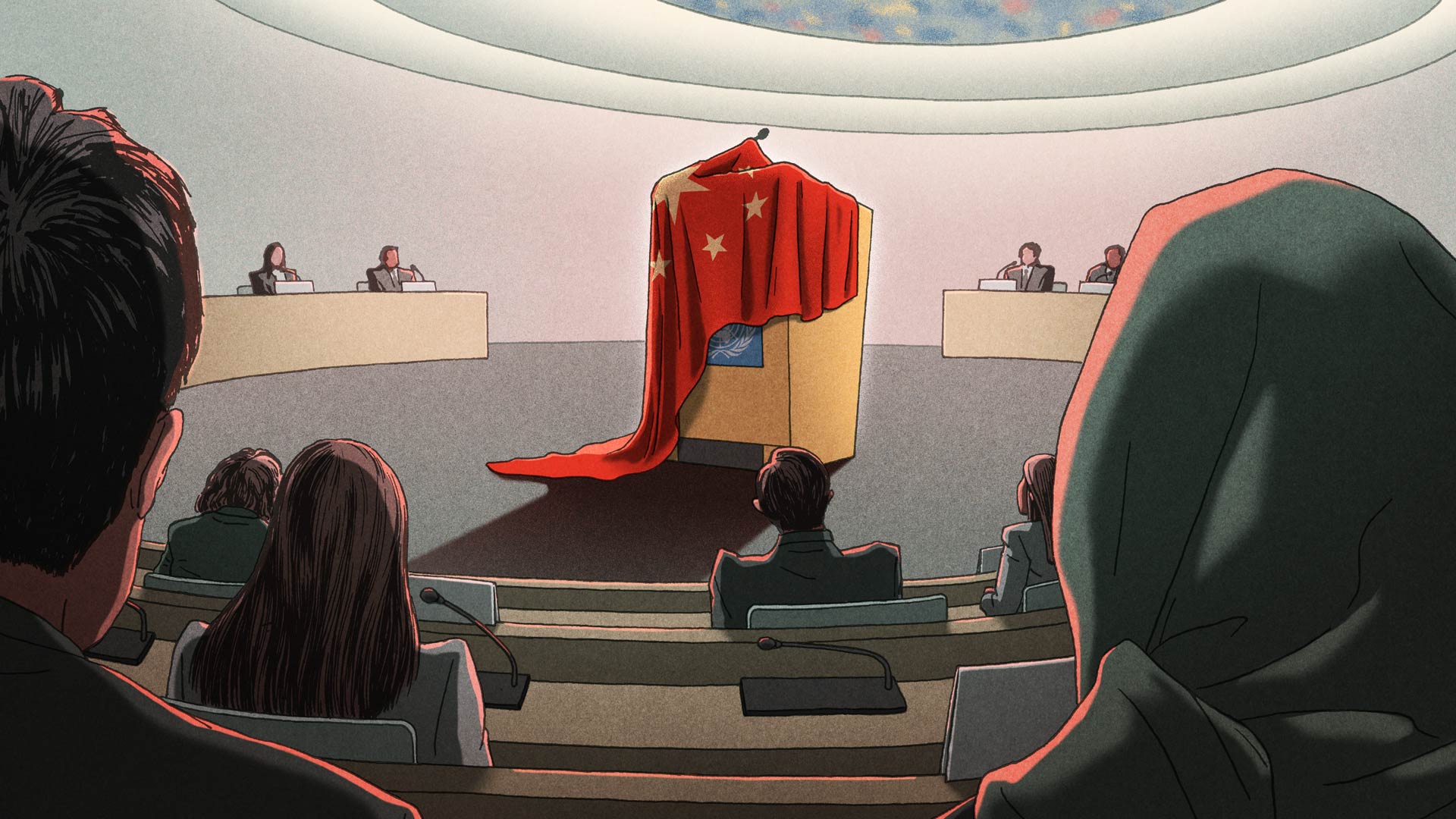

For two consecutive terms a high-ranking Chinese police official has been elected as a member of Interpol’s executive committee, and Meng was named Interpol’s president in 2016. (His presidency ended abruptly less than two years later after authorities detained him on corruption charges during a trip back to China and later sentenced him to 13 years in prison.)

China is Interpol’s second largest contributor, an obligation calculated according to members’ economic weight, spending $13.7 million in 2024, behind the U.S. at $19.8 million. China, which posted 11 officers at Interpol’s General Secretariat in 2023, regularly finances special operations, including some that targeted telecommunication fraud and the trafficking of illegal weapons.

The Chinese government says it has used Interpol to locate, arrest and repatriate at least 479 suspected criminals in the last decade. It also says they have repatriated 62 of “100 Top Red Notice” targets that the government began to publicize in 2015.

In countries that have signed an extradition treaty with China, a red notice can lead to arrest, extradition and deportation. The U.S. does not arrest people solely on the basis of a red notice. Other countries do, including Italy, Albania and France.

By 2016, just two years after Meng’s speech, China was among the top 10 countries that were the subjects of new complaints and information requests by red notice targets and other individuals, according to a report by the Commission for the Control of Interpol’s Files. Also known as the CCF, the commission is made up of international jurists and legal experts and ensures that the data processed through the organization’s system complies with its rules.

‘A black box’

Interpol has no police force of its own. Instead, it draws on police data from democracies and autocratic regimes to compile massive databases that member nations use to share information on wanted criminals and to cooperate on cross-border crimes such as terrorism, human trafficking, financial crime and drug smuggling.

About a decade ago, after human rights advocates and news organizations including ICIJ exposed how Iran, Russia and other authoritarian regimes misused Interpol to round up political opponents and refugees, the organization announced what it said were sweeping reforms.

In 2016, it created the Notices and Diffusion Task Force, made up of lawyers, police officers and other specialists who screen red notices before authorizing their publication in Interpol’s databases. But the task force’s review is limited to information that is publicly available and what is already in Interpol’s databases, as well as data from the authorities who submit the notice requests. It doesn’t investigate the merits of a case and relies on the requesting government’s good faith to ensure information is both accurate and apolitical. If a red notice target doesn’t have much of a public profile, the task force likely will approve a request, lawyers representing suspects told ICIJ. “Politically motivated red notice requests can slip through,” said Charlie Magri, a lawyer who worked as a legal officer for the CCF oversight body.

As part of its reforms, the organization gave more powers and resources to the CCF. The commission — which meets four times a year — reviews, and may even revoke, Interpol’s notices if a subject demonstrates it violated Interpol’s apolitical mission or other rules.

But authoritarian governments, with legal systems under political control, continue to pose a special problem for Interpol, which, experts and human rights advocates say, seeks to navigate its rules while maintaining relationships with the member states who provide financial support.

Because most Interpol procedures are secret, determining whether a red notice is politically motivated or a legitimate attempt to catch a criminal is difficult, these advocates say.

“It’s like a black box,” said Ben Keith, a London-based human rights lawyer who has represented many Chinese nationals, including businesspeople wanted for fraud and Uyghurs accused of terrorism.

An Interpol spokesperson said in a statement to ICIJ that the organization “knows Red Notices are powerful tools for law enforcement cooperation and is fully aware of their potential impact on the individuals concerned, which is why we have robust – and continuously assessed and updated – processes for ensuring our systems are used appropriately.”

The spokesperson, however, said the task force’s original decision to authorize a red notice “can only be based on the information available at the time of publication.”

The targets

ICIJ and its media partners have spoken with eight of China’s red notice targets and reviewed extradition records, confidential CCF decisions and other documents concerning a total of nearly 50 suspects pursued by China through Interpol after the 2016 reforms.

Many suspects discovered they were wanted only after being stopped at a border control. Among the targets were wealthy businesspeople who said they were wanted for criticizing government policies; Uyghur rights advocates who said they had been falsely accused of terrorism after opposing Beijing’s oppression of minorities; a small-town politician who said he was blacklisted after exposing Communist Party corruption; and three entrepreneurs who said authorities were after them for being followers of the Falun Gong spiritual movement, which is banned in China. The most common pretext used by China to obtain a red notice is a financial crime, advocates say.

“If someone accuses someone of murder, there needs to be a body,” said Bromund, the Interpol critic, who is policy director of the Pursuit, a nongovernmental organization that opposes transnational repression. “If someone accuses someone of financial crimes, it is literally ones and zeros in the wrong ledger somewhere.”

Lawyers for red notice targets said they found a range of flaws common to Chinese-requested red notices, including discrepancies between arrest warrants and other documents and thin evidence to substantiate the allegations.

If someone accuses someone of murder, there needs to be a body. If someone accuses someone of financial crimes, it is literally ones and zeros in the wrong ledger somewhere. — Strategic studies specialist Ted Bromund

For example, a court in Southern France recently rejected the extradition of Tang Hao, a major shareholder of a U.S. tech company bidding to acquire the popular Chinese app TikTok. The court stated that the authenticity of the arrest warrant was “questionable,” and cited Tang’s allegation that Chinese authorities requested the red notice after he refused to give part of his profits to a provincial Chinese public security official. Through his lawyers, Clara Gerard-Rodriguez and Pierre-Oliver Sur, Tang declined to comment, as did the U.S. company.

In some cases, targets have also alleged that Chinese authorities used unethical tactics and “psychological warfare” to pressure them.

Turkish police records show that in 2023, Chinese state security officials allegedly paid more than $100,000 to a Uyghur textile trader to spy on Abdulkadir Yapchan, a Muslim Uyghur activist wanted by Beijing for two decades, and others. The records say officials allegedly told the trader to look for a house to buy near Yapchan’s residence as a way to monitor him closely, according to interrogation records obtained by ICIJ’s media partner Deutsche Welle Turkey. China first requested Interpol to issue a red notice against Yapchan in 2003 when the government accused him and 10 other Uyghurs of terrorism and other crimes, charges he vehemently denies. A Turkish court rejected a Chinese request to extradite Yapchan in 2019, finding it politically motivated.

Gao Jianhuan, a political activist who said he moved to Vietnam after witnessing human rights abuses in his native Zhejiang province, was accused by Chinese authorities of defrauding three Chinese citizens in 2017. While en route to Ecuador in early 2023, he was arrested and held at a police station in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, on the basis of a red notice. Gao, a 43-year-old travel agent at the time, was later released after Chinese authorities failed to pursue an extradition request against him, UAE judicial records show. Fifteen months later, Gao was arrested again, in Benin, on the basis of the same red notice, while Interpol’s CCF was reviewing his petition to have his name removed from the organization’s database. While Gao was held in a crowded cell in Cotonou, his lawyer alleged in court filings that “this detention was prolonged as a result of a request made outside the formal extradition procedure” by the Chinese authorities. Gao was eventually deported to China.

Z., a 39-year-old former chairwoman of an online lending firm, spent more than 200 days in an Italian prison after authorities arrested her at the Ancona airport on the Adriatic coast in 2022. Z., who was accused by Chinese prosecutors of “illegally absorbing public deposits,” has alleged in court records that authorities detained her brother in China to force her to return. An Italian court later ordered her release and rejected China’s extradition request, ruling that she could face inhumane and unjust treatment. The businesswoman obtained about $52,000 in compensation from the Italian government for unjust imprisonment, her lawyer Enrico di Fiorino told ICIJ. Through her lawyer, the businesswoman asked her name not be published to protect her relatives in China.

Politically motivated

In the days after his arrest in Bordeaux, H. was bombarded by calls from China. Besides Ma, two other friends and three top security officials all called with the same message: The Chinese government was ready to withdraw the red notice, abandon the extradition request and potentially drop the money laundering charges if H. agreed to return to China and cooperate on the high-profile case against the politician, according to the court records.

While still in a Bordeaux jail, H. learned his family was coming under pressure.

“I had a chat with your wife,” Wei Fujie, then a deputy director of the unit assigned to the Sun Lijun case led by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, said in one of the calls.

“Believe me, I’m speaking as a representative of the supreme power that I can represent,” the official continued. “No prosecution now, plus cancellation of the red notice. …You will not be held criminally liable, will be free to enter and exit [the country], and have bank accounts unblocked. …”

In another call, Erick Tsang, a high-ranking Hong Kong official and a friend, told H.: “They always use the same two tricks. … The first one is to freeze all your money … the second one is to threaten your family.”

“They’re actually unreasonable,” H. later told his friend Ma during their phone conversation. “You see, they even arrested my elder sister in order to threaten me.”

On another recorded call, H. pleaded with Li Jiangzhou, an official sanctioned by the U.S. government for his role in “eviscerating the freedoms” of Hong Kong people, to release his sister.

“No, this is not a condition,” replied Li, the deputy director of Hong Kong’s Office for Safeguarding National Security. “If you return to Hong Kong, your red notice will be canceled. After you meet [the investigators,] I can ask them to process any remaining business.”

In the end, H. chose not to return.

They always use the same two tricks. … The first one is to freeze all your money … the second one is to threaten your family. — Erick Tsang, a high-ranking Hong Kong official and H.’s friend

One month after the call with Ma, in May 2021, Chinese authorities formally asked the French government for H.’s extradition. At the same time, a representative of the Chinese Embassy in France contacted Bordeaux prosecutors three times to “advance” the request, a source familiar with the matter told Radio France reporters, describing such a move as “unprecedented” for an extradition proceeding in Bordeaux.

French authorities began investigating the merits of the extradition request — and soon found problems.

First, the Bordeaux prosecutor asserted the acts alleged by the Chinese authorities would not be considered criminal offenses in France and asked the court to reject the request.

H.’s lawyers, Gerard-Rodriguez and Sur, then told the court that “a certain number of terrifying elements occurred outside the proceedings, ‘off the record’ on China’s initiative: blackmail and threats, false promises to withdraw the charges and the Red Notice, arrest and detention of members of [the businessman’s] family.”

The extradition request, they added, “is just one of the many means (legal or illegal) used by China to obtain the return (voluntary or forced)” of the businessman.

In their statement, the lawyers explained that H.’s only tie to Sun, the defendant in the corruption case, dated to an unrelated business deal in 2018. At the time, Sun asked H. to invest about $5 million in a security company that hired Hong Kong police officers accused of abusing protesters during the pro-democracy movement in the city, the statement said.

In another call, H. told Tsang, the Hong Kong official and friend, that he had made the investment because he didn’t feel he had a choice.

Li and Tsang did not respond to ICIJ’s requests for comment.

In July 2021, the Bordeaux Court of Appeal rejected China’s request to extradite H. A few months later, CCF approved his request to have his name — and red notice — deleted from the Interpol database, though it argued Interpol had done nothing wrong.

In a confidential decision dated January 2022 and reviewed by ICIJ, the CCF said it wasn’t its responsibility to “examine evidence and make a judgment on the guilt or innocence of a subject of a national court.” At the same time, it said Dongguan prosecutors had provided “concrete information” and details on H.’s involvement “to a satisfactory degree.”

However, the Bordeaux court’s conclusions on the “political character of the case” and risks faced by H. if he is sent back to China “cannot be ignored,” the commission said.

Documents and sources behind the China Targets investigation

ICIJ’s China Targets investigation is based on interviews with 105 victims of China’s transnational repression in 23 countries, as well as documents from multiple sources.

H.’s case was one of nearly 300 in which the CCF that year decided to remove a red notice from its systems after finding subjects’ data in violation of Interpol’s rules, an ICIJ analysis of CCF reports shows. In recent years, the number of red notices published every year has stayed about the same, going from 10,718 in 2014 to 12,260 in 2023. Meanwhile, complaints for correction or deletion have surged a whopping 350% in the last decade, according to an ICIJ review of CCF reports.

In its reports, the commission itself has lamented “increased workload and complexity” of applicants’ requests, few resources and other challenges. Lawyers representing applicants have complained of long waiting times, little communication and poor explanations while their clients remain in prison or are stuck in a foreign country waiting to go home.

“The difference between Interpol and other international organizations is [that] the things they do have immediate impact on people’s lives,” said Keith, the London lawyer. “Somebody’s arrested and they’re in prison and that’s it.”

Human rights advocates as well as former Interpol officers who talked with ICIJ also said that Interpol’s lack of transparency and its reluctance to sanction countries that misuse its system have undermined the organization’s credibility.

In 2017, CCF stopped releasing information identifying the countries responsible for the highest number of complaints about red notices and other data included in Interpol’s databases, arguing that the information lacked context and was “potentially ambiguous and could lead to misinterpretations,” the commission told ICIJ.

“The absence of a country-specific breakdown makes it impossible to identify patterns of misuse by individual member countries — an essential step in addressing politically motivated abuse,” said Magri, who had reviewed red notice cancellation requests while a legal officer with CCF’s secretariat from 2017 to 2023. “This is not about shaming countries but about promoting transparency and responsibility.”

According to its charter, Interpol can impose corrective measures on member countries responsible for abusing its system, including enhanced scrutiny of red notice requests as well as a temporary suspension or long-term exclusion from Interpol’s network.

But the organization only rarely makes sanctions public, fearing that targeted governments would be less willing to cooperate with Interpol and its members, Magri said. Interpol has said it imposed corrective measures on several countries since 2012, but named only two so far, Russia and Syria.

China is not on Interpol’s list of six countries currently subject to corrective actions, according to Slovenia’s Interior Ministry in a statement earlier this month to ICIJ’s reporting partner Oštro. The revelation came in response to a series of questions about a red notice case brought by China in that Central European country. Interpol didn’t have a comment.

Magri said Interpol should release the names of all sanctioned member states.

“Public disclosure would enhance trust in Interpol’s processes and reassure the public that steps are being taken to prevent abuse,” he said.

In exile

After the Bordeaux court rejected H.’s extradition, the businessman became engulfed in debts totaling about $135 million, according to Chinese media.

The Chinese government, meanwhile, ordered the removal of all films and television dramas featuring his famous wife, Zhao, from video streaming sites and social media platforms in China. The couple, once celebrated as one of the world’s wealthiest, quietly filed for divorce. ICIJ’s attempts to contact Zhao were unsuccessful.

Zhao was rarely seen in public for three years.

Resurfacing this past December, Zhao posted a message on Weibo, the popular social media platform where she has 83 million followers. She said she no longer wanted to be associated with her ex-husband, H.

Contributing reporters: Géraldine Hallot and Maxime Tellier (Radio France); Simon Leplâtre (Le Monde); Sophia Stahl (paper trail media/ZDF/DER SPIEGEL); Pelin Ünker (DW Turkey); Echo Hui (Australian Broadcasting Corporation); Tobias Andersson Åkerblom (Göteborgs-Posten); Mašenjka Bačić and Uroš Škerl Kramberger (Oštro); Justin Wong (The Post/Stuff); Jelena Cosic, Sam Ellefson, Jesús Escudero, Agustin Armendariz, Delphine Reuter, Jane Tang, Dean Starkman and Whitney Joiner (ICIJ)