PRESIDENT'S WALLET

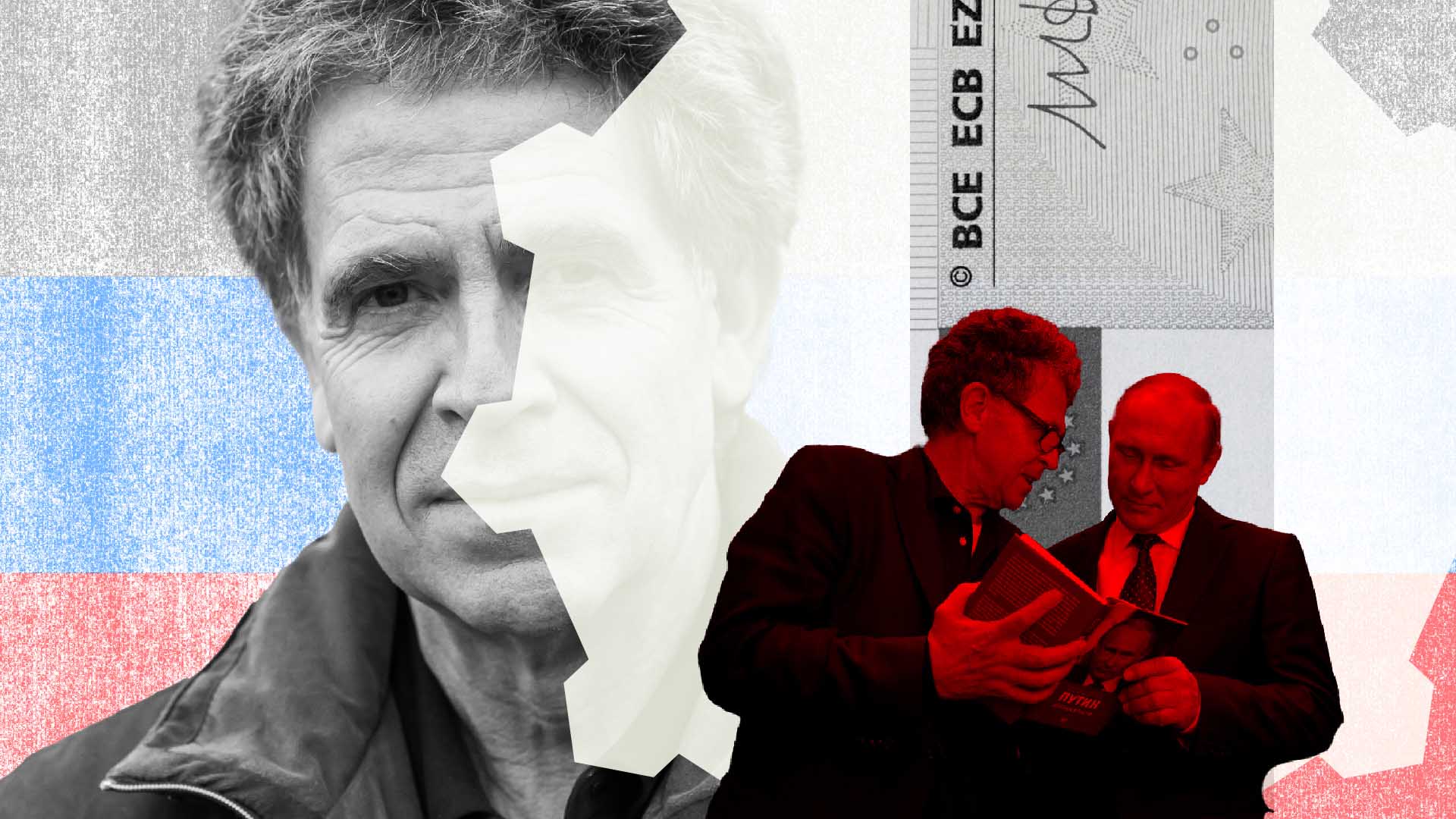

German journalist dubbed the ‘Putin connoisseur’ had secret book deal with Russian oligarch

ICIJ partners reveal that Hubert Seipel — known for his unusual access to the Russian president — agreed to receive around $700,000 from a shell company tied to steel tycoon Alexey Mordashov.

A German journalist who penned a bestseller and made an award-winning documentary about Russian President Vladimir Putin secretly agreed to be paid hundreds of thousands of dollars by middlemen close to an oligarch to write a book about the Kremlin, according to a published report.

The arrangement, uncovered in a new leak of financial records by German reporters working for Paper Trail Media, Der Spiegel and ZDF, provides a striking example of the breadth and sophistication of Russia’s propaganda machine abroad.

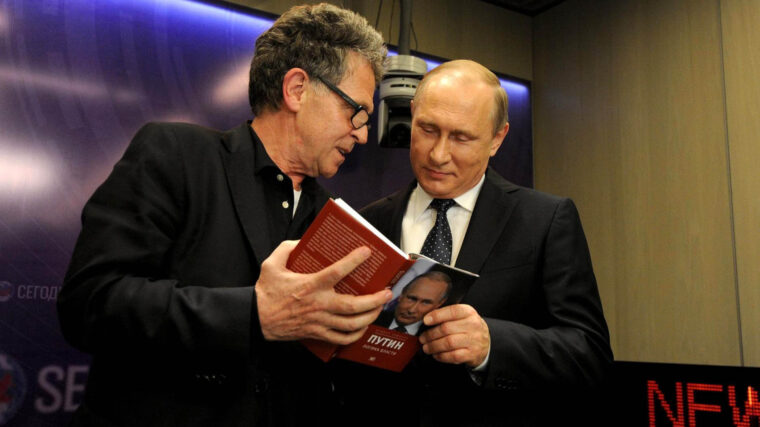

The latest book by veteran journalist Hubert Seipel, “Putin’s Power,” describes the author as “the only Western journalist to have direct, personal access” to the president. “Hardly anyone knows Vladimir Putin as well as Hubert Seipel,” a summary on the publisher’s website reads.

Leaked documents from a Cypriot financial services provider now reveal that, in the past five years, Seipel agreed to receive about $700,000 as a “sponsorship” from a shell company linked to Alexey Mordashov, a Russian oligarch currently under sanction in the U.S. and Europe for his allegedly close ties to the Kremlin. Dmitry Fedotov, a lawyer working for Mordashov’s steel conglomerate, Severstal, served as a witness to the agreement on behalf of the sponsor, the records show.

A handwritten note on a 2018 document says the sponsorship was “for writing a book on [the] political environment in the Russian Federation.” Another note on the same record also referred to a 2013 agreement for “Putin biography.” In 2015, Seipel published a German book with a title that can be translated as “Putin: Inner Views of Power.”

Asked whether he had disclosed to his publishers his relationship with the oligarch, Seipel said that none of the people who worked with him had questioned whether he was “working on behalf of foreign powers.”

Seipel rejected any idea that he is “some kind of Putin agent” and said Mordashov “is by no means from the Russian security or state apparatus,” or connected to the government.

The journalist acknowledged Mordashov’s sponsorship of his books but defended the legitimacy of his work. “Mordashov is an entrepreneur who sponsors projects with private money” and his “support was only meant for the book projects” that were intended to add to the public debate, Seipel said. “The books have led to lively discussions and ideological battles,” he told Paper Trail Media. “Nevertheless, no specific factual errors were found in any of the books.”

Seipel, who is also known in Germany for an exclusive interview with Putin produced for public broadcaster Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR) in 2014, said he has not received any payments from third parties for his documentaries or televised interviews.

“The idea that the broadcasters should have asked me every time whether I had ulterior motives is absurd, to say the least,” Seipel said.

Seipel’s publisher, Hoffmann und Campe Verlag, told Paper Trail Media it had “no knowledge” of the sponsorship agreement. “If these [allegations] prove to be true, we reserve the right to take further steps” in connection with Seipel’s books, the publishing company said in a statement.

NDR told the reporters that it takes the allegations seriously and that Seipel should have disclosed any potential conflict of interest to the broadcaster.

Mordashov and Fedotov did not comment on the deal.

The findings on Seipel’s secret book deal are part of Cyprus Confidential, a cross-border investigation led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and Paper Trail Media, a Munich-based news organization.

The investigation, based on a leak of 3.6 million files from six Cypriot financial services providers and a Latvian firm, shows how complicit operators have helped members of the Russian elite hide billions of dollars in assets from the threat of sanctions. It also sheds light on the role of Cyprus as a key financial and secrecy hub for Putin’s cronies.

About the Cyprus Confidential files

The 3.6 million leaked files at the heart of the Cyprus Confidential investigation come from six financial services providers and a website company.

The records for all of the transactions involved in the book deal were prepared by an officer at PwC Cyprus, the leaked files show. The accounting giant’s Cypriot unit had been working for Mordashov and other oligarchs for at least two decades, helping them shuffle their riches and undermine Western sanctions designed to cut off Putin’s war funding, ICIJ found.

“Cyprus has run out of credibility,” says Alexander Apostolides, an anti-money laundering expert and researcher at the European University Cyprus. “The problem we see is that consistently companies related with this business service sector that are supposed to be regulated … seem to find ways to avoid [oversight] and do the things that are either illegal or at least unethical,” Apostolides told ICIJ’s German media partners.

In a statement to ICIJ, PwC said that “following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, PwC Cyprus has terminated relationships with approximately 150 client groups.” PwC did not answer ICIJ’s specific questions about the firm’s clients, citing confidentiality reasons.

The ‘Putin connoisseur’

Russia’s war on Ukraine and subsequent attempts by the Kremlin to shape the narrative about the conflict, at home and abroad, have put a spotlight on the Putin regime’s strategy to influence foreign media and opinion.

Most recently, Italian TV shows saw an influx of pro-Putin commentators and Russian propagandists seeding doubts about the extent of the brutality of Russia’s operations, including the killing of Ukrainian civilians at the hands of Russian soldiers in the village of Bucha. Early this year, the U.S. government-funded media outlet Voice of America declined to renew the contracts of two Russian journalists accused by VOA staff of supporting “all Russia’s propaganda narratives.” In Latin America, the Kremlin has been spreading anti-Ukraine and anti-NATO messages across the region using influencers on Spanish-language social media, according to a study by the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab.

In Germany, Seipel, who has worked as a foreign correspondent for prominent German outlets, including Stern magazine and Der Spiegel,and as a freelance television author for public broadcaster NDR, has cultivated an image of a “Putin connoisseur.” Now in his 70s, he has boasted of having met the Russian autocrat many times and even played billiards with him during the shooting of his 2012 documentary, “I Putin, a Portrait.” In the film ー criticized by some local media as a microphone-holding exercise rather than objective journalism ー the two converse in German, a language Putin mastered in the 1980s when he worked as a KGB officer in Dresden, then part of East Germany. The documentary was viewed by nearly 2 million people and broadcast 51 times, according to NDR.

In 2021, Seipel’s unusual access to Putin led a radio commentator to ask the journalist during an interview whether he had ever received any payments from the Kremlin.

“Have you received any honoraria, if I may ask so directly, from Russia?” the radio host, Wolfgang Heim, asked.

“No!” Seipel replied.

But the leaked documents tell a different story.

According to the sponsorship agreement included in Cyprus Confidential, in 2018 and 2019, Seipel was supposed to receive two payments from a British Virgin Islands company named De Vere Worldwide Corp.

The leaked records show that De Vere Worldwide belonged to Igor Voskresensky,who has served as a director for a power equipment manufacturing firm owned by Russian billionaire Mordashov, according to the company’s website. In 2018 and 2019, two Mordashov companies transferred roughly $709,000 in total to De Vere Worldwide. After each money transfer, De Vere Worldwide paid Seipel, the records show.

Mordashov was sanctioned by the European Union and the U.S. in 2022 for his allegedly close ties to Putin. Though he has repeatedly denied being involved in politics, Mordashov is also a shareholder in Bank Rossiya, which was sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department because of its alleged role as the personal bank for Russian senior officials.

The purpose of the payments to Seipel was a book that was “expected to be published in 2019,” the sponsorship agreement said. The sponsoring company was “to support the development of the [book] and to make this political and historical development available to a wider audience.” It would also provide the author “with reasonable logistical and organizational support during his research in Russia,” the document said.

In 2021, he published the German-language book “Putin’s Power.”

Reached on the phone by Paper Trail Media, Voskresensky denied any links with De Vere Worldwide and hung up. He did not respond to a written request for comments.

In an appearance on an Austrian TV show in February, Seipel said he is writing a book about the war in Ukraine and that he has met Putin in Moscow once since the beginning of the conflict. Seipel said he asked the Russian president why he had started the war. Putin didn’t give him a direct answer. Instead, he asked more questions.

Sophia Baumann, Maria Christoph, Carina Huppertz, Bastian Obermayer, Frederik Obermaier and Timo Schober (Paper Trail Media/Der Spiegel), Marta Orosz and Hans Koberstein (ZDF) contributed to this report.