A dozen blocks from the nearest subway stop and a world away from posh cafes, the apartment building on 44th Street in Queens was for decades the sort of New York City building that would attract little attention. The ground floor had a pizza-by-the-slice shop with red walls, a $5 lunch special and a neon sign advertising “hot pizza.” Upstairs, the building had been home to a construction worker, a union doorman who worked late shifts in Manhattan lobbies and someone who worked at a small bank down the street.

The block is lined mostly with two-story brick row houses, making it sunnier than many spots deeper into the city. There’s the constant soundtrack of planes taking off from nearby LaGuardia Airport.

The life of an apartment building is always about change of one kind or another, but what was about to happen to the four-story building on 44th Street spoke to darker activities of war and covert finance happening a world away.

It had come under close scrutiny of a private equity firm working with overseas investors quietly buying rental buildings in the New York area via shell companies — the faceless entities that move billions in secretive funds through the U.S. economy every year. The firm had completed a painstaking analysis of the modest 44th Street building and concluded that under new ownership, its tenants could be charged far more in rent, making it far more in profit.

On its face, the building’s sale in 2014 was unremarkable: just another anonymous limited liability corporation entering a hot real estate market, raising rents and driving longtime tenants out. But a trove of leaked records provides a rare view into the secret forces profiting from this deal and many like it.

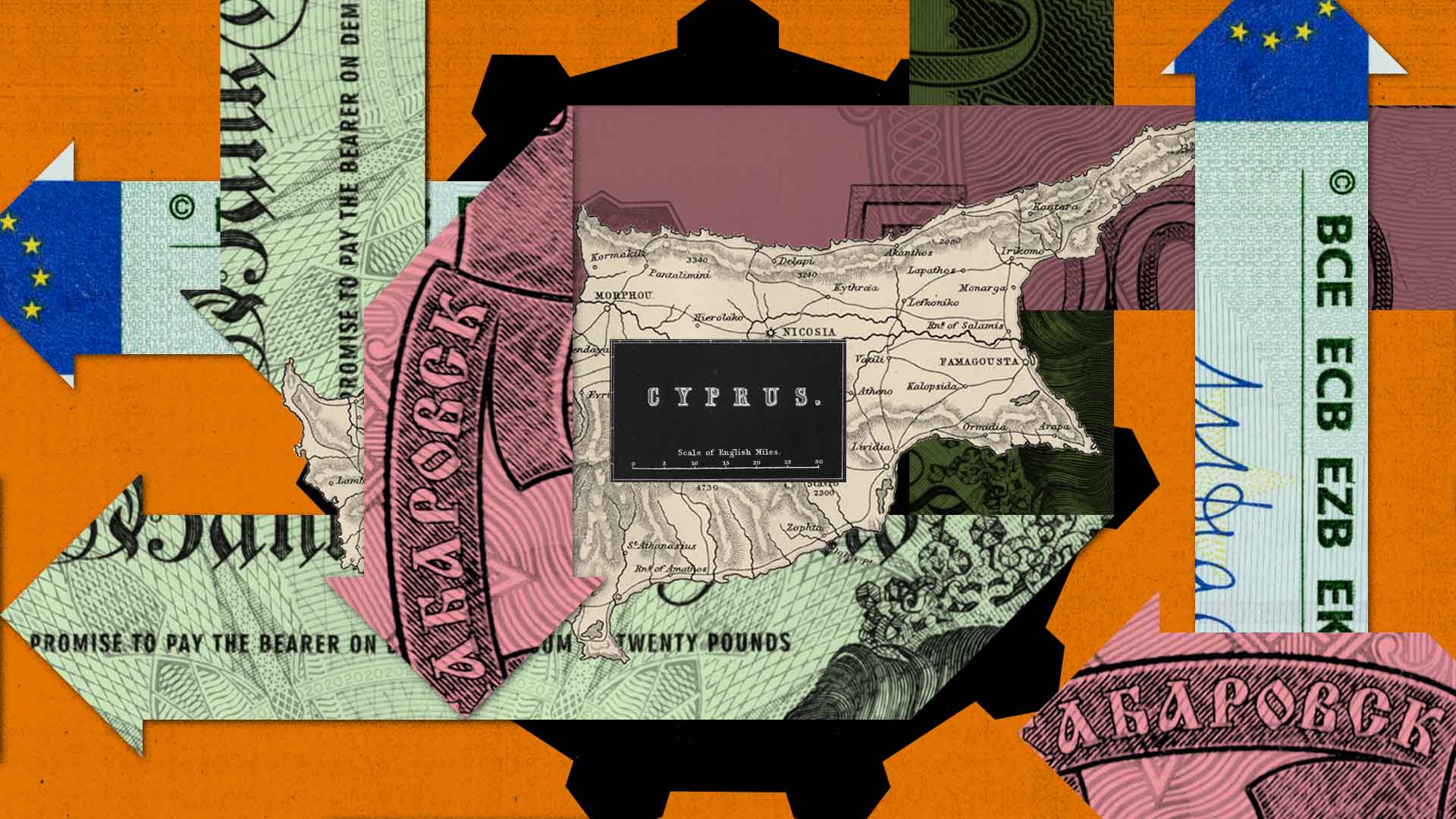

Behind the sale was a financial firm applying a highly analytic approach to profit-making, and a now-sanctioned financial fixer in Cyprus who made his wealth hiding money for billionaires in Vladimir Putin’s inner circle. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year, the United Kingdom targeted the Cypriot offshore services provider, Demetris Ioannides, in a crackdown on financial professionals “who knowingly assisted sanctioned Russian oligarchs to hide their assets in complex financial networks.”

The records provide vivid detail of a phenomenon affecting many millions of renters around the world, the extent to which secretive global investment structures have permeated the real estate market well beyond the luxury condos and beachfront mansions of the rich. These days, an increasingly hot investment for the ultrawealthy are modest homes and apartment buildings like the one on 44th Street in Queens.

This shift not only poses new challenges for authorities tracking money linked to Putin’s enablers, but has also raised complaints from tenants feeling the squeeze of a new breed of aggressive corporate landlord and from prospective home buyers who can’t navigate a market that feels out of whack. In 2017, a United Nations report warned that the “expanding role and unprecedented dominance of financial markets and corporations in the housing sector” were contributing to increases in poverty, evictions and homelessness around the world. Years later, those increases have continued at a daunting pace.

The leaked documents detailing the Queens building are part of Cyprus Confidential, a cache of 3.6 million documents at the heart of a global investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and 68 media partners. Hundreds of thousands of these records come from Ioannides’ own firm, MeritServus.

About the Cyprus Confidential files

The 3.6 million leaked files at the heart of the Cyprus Confidential investigation come from six financial services providers and a website company.

Ioannides’ investment in the New York building was part of a wave of purchases since the 2008 financial crisis that swept millions of rental homes under the control of aggressive financial firms. The financial industry’s rush on U.S. housing has been aided by the country’s deep level of financial secrecy, which allows investors with checkered histories or questionable sources of income to invest millions in the country without any public disclosure. After years of lobbying, activists won a major victory in 2021 with Congress’s passage of the Corporate Transparency Act, promising to lift the veil of secrecy from U.S. shell companies. The implementation of the law, however, has been marred by loopholes, delays and infighting that call into question the law’s practical effect.

ICIJ previously reported on major secret investments in U.S. real estate facilitated by sophisticated investment firms. In 2021, ICIJ focused on apartment buildings in Florida owned in part by offshore trusts holding hundreds of millions of dollars for the Legion of Christ, a wealthy Roman Catholic order disgraced by an international pedophilia scandal. As part of that series, ICIJ also reported on the secret billionaire investors who quietly bought into a massive scheme to buy up thousands of foreclosed suburban homes in the wake of the 2008 crisis.

The big profits that investment funds advertise can lead to tenants getting squeezed, according to David Szakonyi, an assistant professor of political science at George Washington University.

“These are investors who are really concerned with extracting maximum revenue from their leases,” Szakonyi said. “It does not bode well for renters.”

The New York squeeze

Demetris Ioannides started in Cyprus’ growing wealth management industry in 1988, founding the Cyprus office of the accounting giant Deloitte. Over the next two decades, Ioannides made a name for himself among an elite group of Cypriot lawyers and accountants that have helped to move vast fortunes — many of questionable origin — out of Russia and into Europe and elsewhere. In 2005, he set up MeritServus, and managed to bring some of Russia’s wealthiest citizens to his firm, including media magnate Konstantin Malofeyev and oil-trading billionaire Roman Abramovich. According to an ICIJ analysis, MeritServus appears to have worked closely with Abramovich, helping to administer a web of more than a dozen offshore trusts in Cyprus and the Channel Island of Jersey — several of which he would pass on to his children in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and more than 200 companies, mainly in Cyprus, the British Virgin Islands, Jersey and the Isle of Man. Abramovich, a close Putin ally, gained celebrity status in Europe after purchasing U.K.’s Chelsea Football Club in 2003.

MeritServus did not respond to a request to comment on this story.

Malofeyev was placed under sanctions by the EU and the U.S. after Russia’s invasion of eastern Ukraine in 2014. U.S. authorities described him as both a key propagandist for Putin’s war effort and a major funder of Russia-aligned paramilitary forces that have been fighting in eastern Ukraine for years. More recently, Malofeyev called Russia’s invasion of Ukraine a “holy war.” MeritServus appears to have worked with Malofeyev until spring 2017, assisting with millions of dollars in transactions even while he was under sanctions in the U.S. and EU, according to the Guardian.

While helping to oversee business deals by Abramovich and his other clients valued at hundreds of millions of dollars, Ioannides and two of his family members were looking for investments in New York real estate. In March 2014, Triena Capital Partners, a low-key private equity firm that lists its address at a Manhattan P.O. box, sent the Ioannides family a document describing the 44th Street apartment building in Queens as an “under-utilized asset with the opportunity to significantly increase rental income.”

The document assured investors that the building’s rents could be swiftly raised by 62%, breaking out the exact percentage jump for each unit. This would be carried out partly by renovating a handful of apartments and updating the lobby and intercom system. The document said rent hikes could also come from eliminating rent control — a hallmark policy of affordable housing in New York — in certain units in order to increase tenants’ fees without restraint, according to the document. In some cases, Triena could pay rent-stabilized tenants to leave, a tactic known as a “buy-out.” Triena said it could also deploy “private investigators” and surveillance cameras to determine whether tenants had violated rent stabilization policies by subletting their apartments. “The benefit, of course, is an increase in rent,” the document said.

The plan called for selling the building after just a few years for a big profit.

Triena Capital Partners did not respond to requests for comment.

In mid-2014, Ioannides and his family members became the largest investors in the building. Although unaware that portions of their rents were now being funneled to Cyprus, tenants say they noticed a change in the life of the building. Under the ownership of Ioannides and other investors, rapidly rising rents drove out some of the building’s original tenants, according to two people with long-term knowledge of the building.

The ongoing ease of secrecy

Before 2014, Jimmy Rodriquez, a 19-year resident of the building, frequently saw the previous owner with whom he was on a first-name basis. After Ioannides invested in the building, he had no idea to whom he was paying rent.

In records ICIJ reviewed, the Ioannides family bought into New York’s real estate market as early as 2010, purchasing an upscale apartment building in Lower Manhattan. In that deal, they also used a set of shell companies registered in the British Virgin Islands and Delaware to make the purchase. (The British Virgin Islands has consistently ranked as a top jurisdiction of financial secrecy and money laundering, while Delaware has long served as the classic entranceway into the U.S. market for those seeking to conceal their business.) A review of filings for the Delaware firm that helped invest in the building on 44th Street shows no clue of the Cypriot family’s ownership of the firm.

“You get an opaque slate when you try to search for information on a Delaware firm,” Lakshmi Kumar, the former policy director of Global Financial Integrity who reviewed records detailing the Ioannides deal, told ICIJ. In that state, “the secretary of state’s office collects almost nothing of use about a company. There’s an enabling environment of laws in Delaware that supports people looking for secrecy.”

The 2021 Corporate Transparency Act mandated that U.S. authorities collect ownership information on all domestically registered companies, including those in Delaware. However, the database would remain secret to all but law enforcement agents and some banking officials. Even those authorized users would have such strictly limited access that the database would be nearly useless, according to critics of the law’s implementation.

In March of 2022, just weeks after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the building at 44th Street transferred ownership again. Ioannides and his co-investors sold it to a large real estate firm for $7.3 million — even more than what the detailed investment strategy had projected seven years earlier.

The previous year, Ioannides and other co-investors bought another apartment building in New York, this one on Downing Street in the Clinton Hill neighborhood of Brooklyn — through a shell company in Delaware, which owned a shell company in New York. Residents told ICIJ they’ve noticed big changes at the building.

There’s an enabling environment of laws in Delaware that supports people looking for secrecy.

— Lakshmi Kumar, former policy director of Global Financial Integrity

One Downing Street resident recently pleaded with management to reconsider a $600 monthly rent increase this year, in part due to complaints regarding water leaks and a partially collapsed ceiling. The building’s management was unmoved. “The owners hired a market analyst to determine each unit’s price, and so that is their decision,” the building’s manager told the renter in an email in June.

A 30-year resident of the Downing Street building who spoke on the condition of anonymity said he would often see the previous owner of the building, whom he referred to by his first name. “He was very responsive to everyone’s needs — we had his cell on speed dial,” said the resident, who says it’s become difficult to get management’s attention for repairs. “It’s a little tricky. You feel like you’re kind of lost.”

The resident said the new ownership parallels what he’s been seeing throughout the neighborhood.

“This block has had its ups and downs over the years,” he said. “A lot of buildings are owned by investment funds now.”

Brenda Medina contributed to reporting.