WASHINGTON, D.C. — The first sign of trouble came as Bill Rogers was mowing his lawn one morning in January 2007. “As I would go back and forth with the mower, I would run out of air,” says Rogers, 67, of Palm Bay, Fla.

Rogers went to the doctor and learned that his right lung was full of fluid. Three days later he was diagnosed with mesothelioma, a lethal tumor that occurs in the lining of the chest or the abdomen and is almost always associated with asbestos exposure. “I’d heard of it, but I didn’t really know what it was,” he says. “They told me it’s not a good cancer to get.”

That Rogers is alive more than three years after his diagnosis is something of a miracle. To him, the source of his illness is clear: He worked on or around asbestos-containing automobile brakes, mostly at General Motors dealerships, for 44 years. He and his co-workers had used compressed-air hoses to clean out brake drums, where debris from worn asbestos brake shoes would collect, and had filed and sanded the shoes when installing new brakes. Although he routinely wore a respirator while sanding plastic filler during body work, he says, no one ever told him he needed one for brake work.

Rogers sued GM, Ford, Chrysler, and seven manufacturers and suppliers of brakes and clutches in 2008 and settled with the last of them in 2009. He is among hundreds of former mechanics and body shop employees known to have developed mesothelioma after working on brakes, clutches and gaskets, which contained the most common form of the mineral —chrysotile, or white, asbestos – well into the 1990s.Many have sued auto manufacturers and parts makers, litigation that reflects the unceasing burden of asbestos disease in the United States.

Asbestos has decimated the ranks of miners, millers, factory workers, insulators and shipyard workers, some of whom began filing workers’ compensation claims as far back as the 1930s. The modern era of asbestos lawsuits began the 1970s with claims from these same groups of workers. Many took in massive doses of fiber and died of diseases such as asbestosis, which can develop within a decade of initial exposure. Some of the cases involved mixtures of amosite, or brown, asbestos, which is no longer used, and chrysotile.

In court now, aside from a few heavily exposed workers, are mechanics, teachers from asbestos-filled schools, and wives and children of workers who brought home asbestos on their clothing. Most of these people had relatively light exposures and developed mesothelioma, a disease that can take 30, 40 or even 50 years to appear.

Although asbestos use in the U.S. plummeted from a peak of 803,000 metric tons in 1973 to just 1,460 metric tons in 2008, the nation’s epidemic is far from over. As many as 10,000 Americans still die of asbestos-related diseases each year; one expert estimates that 300,000 or so will die within the next three decades.

A Mounting Toll

Once broadly utilized by U.S. industry — not only in brakes but also in construction, insulation and shipbuilding — asbestos was heralded for its remarkable resistance to fire and heat. Strong and inexpensive, the naturally occurring, fibrous mineral acquired a darker reputation in the 1960s as its health effects became widely known.

Internal documents showing corporate knowledge of the mineral’s carcinogenic properties began to surface, and by 1981 more than 200 companies and insurers had been sued. The following year, the nation’s biggest maker of asbestos products — Johns Manville Corp. — filed for bankruptcy protection in an effort to hold off the tide of litigation. From the early 1970s through 2002, more than 730,000 people filed asbestos claims, resulting in costs to the industry of about $70 billion, according to a 2005 study by the RAND Corp. Of this amount, about $49 billion went to victims and their lawyers, and $21 billion went toward other legal costs.

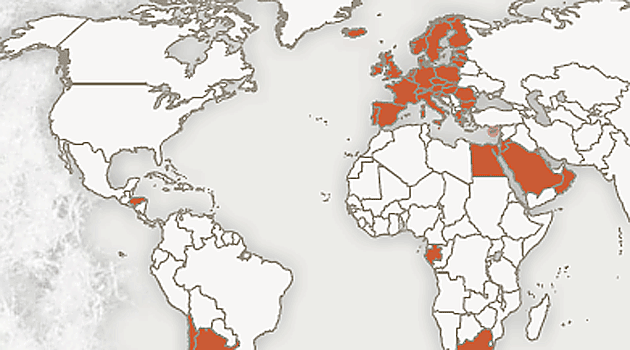

Asbestos use has largely moved overseas, fueled by an aggressive industry campaign that has pushed up chrysotile consumption in fast-growing countries like China, Brazil, and India. Banned or restricted in 52 countries, asbestos products can still be sold in the U.S. but are largely limited to auto and aircraft brakes and gaskets. China, the world’s leading consumer, used 626,000 metric tons of asbestos in 2007 — 350 times the amount used in America that year.

The decline in usage in the U.S., however, has done little for those already exposed — and for those who continue to be at risk. Long latency periods for mesothelioma and lung cancer ensure that there will be victims for years to come, health experts say. Last year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 18,068 Americans died of mesothelioma from 1999 through 2005, with the annual toll edging toward 3,000. Another 1,500 or so die each year of asbestosis, a rate that has “apparently plateaued,” according to the CDC. The number of asbestos-related lung cancer deaths is harder to pin down given theubiquity of smoking, but could be as high as 8,000 per year. Dr. Richard Lemen, a former assistant U.S. surgeon general who consults for plaintiffs in asbestos cases, has cited estimates of 189,000 to 231,000 worker deaths from all asbestos-related diseases from 1980 to 2007. “Another 270,000 to 330,000 deaths are expected to occur over the next 30 years,” he told a Senate committee in 2007.

If Lemen’s figures are correct, that would put the death toll from America’s asbestos age at a half-million people. In its 2005 study, RAND similarly projected 432,465 asbestos-related cancer deaths from 1965 through 2029; this number excludes fatal cases of asbestosis.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency tried to ban asbestos in 1989 but was stopped by an industry lawsuit. Legislation to impose a ban has failed to pass since Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash, introduced it in 2002. Murray has pointed out that imported asbestos brakes are still being sold for older vehicles, putting both professional mechanics and weekend tinkerers at risk, and that asbestos can be found in a variety of items. Laboratory tests commissioned by the Asbestos Disease Awareness Organization (ADAO), a victims’ advocacy group, have revealed the presence of asbestos in products as diverse as window glazing made in the U.S. and a toy fingerprinting kit made in China. ADAO’s CEO, Linda Reinstein, says she is hopeful that proposed revisions to the notoriously weak Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976 would close loopholes that allowed the 1989 ban to be overturned.

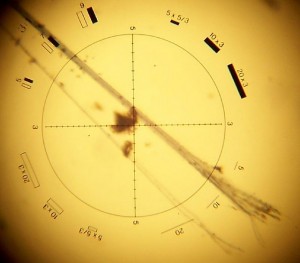

Experts say that the current U.S. workplace standard for asbestos — 0.1 fibers per cubic centimeter of air, adopted by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in 1994 — still allows a worker to inhale more than 1 million fibers over the course of a day. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) estimates that exposures at this level will produce five lung cancer deaths and two asbestosis deaths for every 1,000 workers exposed over a lifetime. Federal officials believe that 1.3 million workers in general industry and construction and 45,000 miners are still exposed to asbestos.

$43 Million of Pro-Industry Science

Mindful of their potential liability on brake linings, GM, Ford and Chrysler have fought the current round of mesothelioma lawsuits with vigor. Court records show that the three have paid nearly $43 million since 2001 to scientific experts at two consulting firms — ChemRisk and Exponent — who have testified that the amounts of chrysotile fibers released from the handling of brake shoes (used in older drum brakes) and pads (used in newer disc brakes) were either harmless or in insufficient quantities to cause disease.

Several of these experts — most notably Dennis Paustenbach, president of ChemRisk and former vice president of Exponent — have published papers in peer-reviewed journals concluding that brake mechanics are not at increased risk of developing mesothelioma or lung cancer. The papers are offered as evidence by defendants seeking to avoid financial blows like the $15 million verdict returned against Ford by a Baltimore jury on April 28. In that case, Joan Dixon, a 68-year-old grandmother, died of mesothelioma after washing her husband’s asbestos-coated work clothes for 14 years. Her husband, Bernard, had done part-time brake work in a garage that specialized in Ford vehicles. A ChemRisk toxicologist, Brent Finley, was a defense expert in the case. A Ford spokeswoman declined to comment on the verdict.

Several of these experts — most notably Dennis Paustenbach, president of ChemRisk and former vice president of Exponent — have published papers in peer-reviewed journals concluding that brake mechanics are not at increased risk of developing mesothelioma or lung cancer. The papers are offered as evidence by defendants seeking to avoid financial blows like the $15 million verdict returned against Ford by a Baltimore jury on April 28. In that case, Joan Dixon, a 68-year-old grandmother, died of mesothelioma after washing her husband’s asbestos-coated work clothes for 14 years. Her husband, Bernard, had done part-time brake work in a garage that specialized in Ford vehicles. A ChemRisk toxicologist, Brent Finley, was a defense expert in the case. A Ford spokeswoman declined to comment on the verdict.

In a separate amicus brief filed with the Michigan Supreme Court in 2007, more than 50 physicians and scientists took aim at industry consultants retained in the brake litigation. “It is in no way surprising that the experts and papers financed by these manufacturers conclude that asbestos in brakes can never cause mesothelioma,” the brief says.

The brief contends that Paustenbach’s work on asbestos follows a “business model” under which he publishes exculpatory papers on compounds – such as hexavalent chromium, the groundwater pollutant at the center of the Erin Brockovich case in California – that are the subject of lawsuits. Paustenbach strongly denies the charge. Records show that his firm, ChemRisk, was paid almost $12 million by the three automakers from 2001 to 2009.

In an e-mailed statement, Paustenbach maintained that he is an impartial scientist and pointed to a pair of studies on radiation and an industrial chemical in which he delivered bad news to his funders. “Our thorough and independent research and analysis stand on their own merits,” he wrote of his work on asbestos, “and there has been no specific credible challenge to the conclusions we drew.”

A scientist with Exponent, which received $31 million from the automakers, agreed with Paustenbach. Epidemiological studies “have shown quite convincingly that neither lung cancer nor mesothelioma risks are increased among workers engaged in automotive, including brake, repair,” Dr. Suresh Moolgavkar wrote in a statement.

Ford said in a statement that the “vast majority of money” it has spent on consultants like ChemRisk “is directly related to expert costs incurred in defending the Company against meritless lawsuits … and is not related to the funding of scientific studies.” A spokesman forChrysler declined to comment; a GM spokesman did not respond to requests for comment.

Sixty Years of Warnings

Government warnings about asbestos in brakes go back decades and remain in effect. As long ago as 1948, a National Safety Council newsletter cautioned, “Asbestos used in the formulation of brake lining is a potentially harmful compound.”

A bulletin issued by NIOSH in 1975 warned that brake work could produce “significant exposures” to asbestos and recommended that employers put dust-control measures in place; nearly one million workers were at risk, the institute said. NIOSH held meetings on the subject in 1975 and 1976; among those present were representatives of Ford, GM and Johns Manville, then the nation’s biggest manufacturer of asbestos products.

The message never filtered down to people like Bill Rogers. “There were no warning labels on the [brake shoe] boxes that said it was harmful to you,” he says. “Nobody ever seemed to talk about it.” Gary DiMuzio, a lawyer who has represented about 200 mesothelioma victims, says that the automakers and brake lining manufacturers did not give mechanics and vehicle owners “a realistic appraisal of the risks they were facing and how to minimize those risks.” Techniques to limit asbestos exposure — ventilation, the use of water to curb dust — were “widely discussed in the 1930s,” DiMuzio says. “It wasn’t rocket science. This was basic engineering and they just didn’t want to do it." No warnings appeared on brake products until well into the 1970s, he adds, “and those warnings were inadequate.”

As a mesothelioma sufferers go, Rogers is doing well. The tumor appears to be contained. Still, he says, “The thought of having cancer and knowing there’s no cure for it works on your mind.”

Mesothelioma “sort of creeps and crawls,” creating a sense of gradual suffocation, says Dr. Alice Boylan, a critical care specialist at the Medical University of South Carolina. The average life expectancy for a victim after diagnosis is nine months to year, a sobering statistic for someone conditioned to save lives. “It’s really wrenching,” Boylan says. “You can help people die to some degree, but not to save one person is pretty hard.”