SÃO PAULO — Inching along at rush hour in her battered black Chevrolet Corsa, Fernanda Giannasi joked about the pariah status she’s attained with the Brazilian asbestos industry. “I have no name,” she said. “I’m just ‘That woman.’”

No wonder. Giannasi, an inspector with the federal Ministry of Labor and Employment, has been trying to shut down the industry for the past quarter-century. She says that white asbestos — mined in the central Brazilian state of Goiás, turned into cement and other domestic products and increasingly sent abroad — has taken countless lives and will take countless more unless it is banned nationwide. The idea that it can be used safely, she says, is “a fiction.”

The 52-year-old Giannasi has many admirers in the global public health community. One local doctor calls her the “Brockovich of Brazil,” a nod to Erin Brockovich, the California file clerk who blew the whistle on water pollution by Pacific Gas & Electric and inspired a feature film. Giannasi’s true constituency, however, lies in places like Osasco, a graffiti-scarred, blue-collar city west of São Paulo and home to Brazil’s most notorious asbestos cement factory for 54 years.

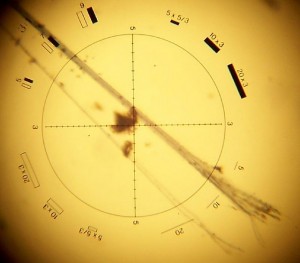

The factory, owned by a company called Eternit, opened in 1939 and was, for most of its existence, thick with asbestos fibers, former workers say. Eliezer João de Souza, 68, worked there from 1968 to 1981, cutting asbestos sheets and corrugated tiles into various sizes. “It was full of dust everywhere,” de Souza says. “You could see it through the sunlight.” Workers had no respiratory protection until 1977, when they were given cheap paper masks, says de Souza, who had small tumors removed from his pleura — the thin membrane that covers the lungs and lines the chest cavity — in 2000. At one point “they called the workers in and took X-rays, but they never showed us the results,” he says. “It was always a game of lies.”

João Batista Momi, 81, spent 32 years at the plant — “It was dirty the whole time,” he says — and developed asbestosis. He sued his former employer in 1998 and won but, because of a company appeal languishing in the Brazilian Supreme Court, has yet to receive any compensation. José Antonio Domingues, 71, had his cancerous right lung removed in 2008, 17 years after he left the plant. He had worked there for 15 years. “It was black inside,” he says. “I’m happy I’m still alive.”

A Top User and Exporter

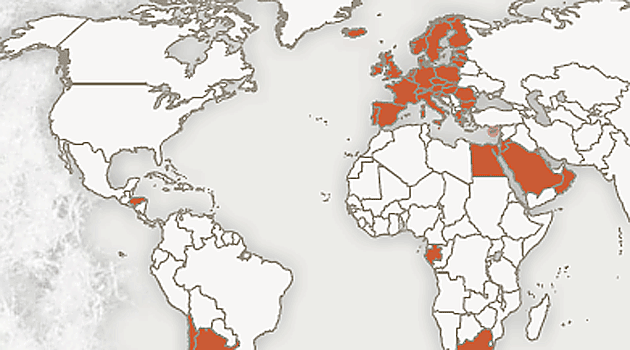

The three men belong to the Associação Brasileira dos Expostos ao Amianto (ABREA) — the Brazilian Association of People Exposed to Asbestos. It is one of more than 70 victims’ groups that have formed around the world, mostly in the past two decades, as the use of asbestos has spread to fast-growing countries and its dangers have become better known. Once widely used in the U.S. and Europe for construction materials and insulation, asbestos is now banned in the European Union and limited to a handful of products, such as automobile brake linings, in the United States. Fifty-two countries have banned or sharply restricted use of the fibrous mineral, long valued for its heat and fire resistance.

Fueled by an aggressive industry campaign, however, the use of chrysotile, or white, asbestos use has grown markedly in the developing world, led by such countries as China, India, and Brazil. With the mineral’s new life in emerging markets, the cumulative death toll from asbestos may reach 10 million by 2030, experts say.

Thousands of those deaths are expected in Brazil, now the world’s third-biggest producer of asbestos. Brazil is also the world’s third largest exporter — shipping mainly to Asia as well as to countries like Colombia and Mexico. And it is the world’s fifth largest user, consuming 94,000 metric tons in 2007 — more than 50 times the amount used in the United States that year. The Brazilian asbestos industry claims to generate 2.5 billion reais — about $1.3 billion — for the nation’s economy each year. The 11 companies that mine asbestos and make asbestos-containing products in Brazil directly employ 3,500 but say they account for 200,000 jobs when one includes construction workers, dealers, and others.

At the heart of the industry is the Brazilian Chrysotile Institute. Public records show that the institute, based in Goiás, has taken in more than $8 million from the industry since 2006, funding used to promote asbestos use across Brazil. A prosecutor in the state is seeking dissolution of the institute, a self-described public interest group with tax-exempt status. The prosecutor charges in a court pleading that the institute is a poorly disguised shill for the Brazilian asbestos industry, which provides virtually all of its budget. Having inflicted “social damage stemming from [its] illegal practices,” the institute should pay 1 million reais (about US$550,000) in damages and a fine of 5,000 reais (US$2,800) for every day it remains open, the pleading says. In a statement to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a spokesman for the institute denied the allegations, saying the group “ensures the health and security of workers and users, protection of the environment and [providing of] information to society.”

Eternit and “The Bill Gates of Switzerland”

When ABREA was formed in 1995, it had about 470 members, mostly from the Eternit plant in Osasco. “At least 30 percent have died in the last 14 years,” says its president, de Souza. At least 10 have died of mesothelioma, a rare cancer that often starts in the pleura and is virtually always tied to asbestos exposure. The factory relied mainly on white asbestos, Giannasi says, though it also may have used “very small amounts” of blue into the mid-1960s. Industry representatives and some scientists maintain that blue and brown asbestos – no longer mined or used – are more lethal than white, a position disputed by many health experts.

Fuming about what they believe to have been gross corporate misconduct, de Souza and his fellow retirees are following a criminal trial in Turin, Italy, where two former shareholders in the Swiss Eternit Group — including onetime chairman Stephan Schmidheiny, a philanthropist dubbed “The Bill Gates of Switzerland” by Forbes magazine for his billion-dollar commitment to poor entrepreneurs in Latin America — stand accused of precipitating an environmental disaster. The charges stem from conditions at an Eternit asbestos cement factory in the Italian town of Casale Monferrato; some 2,000 people who worked in or lived near the plant have died of asbestos-related diseases. “Considering that hazardous exposures experienced in Italy were replicated elsewhere, there must be hundreds of thousands of people who have died from their exposures to this company's asbestos products,” says Laurie Kazan-Allen, coordinator of the International Ban Asbestos Secretariat in London.

In an e-mail, spokesman Peter Schuermann wrote that Schmidheiny “cannot understand why he should be made responsible for the entire 80-year history of the Italian Eternit as one of the main defendants.” The Swiss Eternit Group was the biggest shareholder in the Italian plant for only its last 10 years, Schuermann wrote, and implemented “workplace safety measures which were in accordance with the highest standards.” According to Schuermann, the Swiss group sold its shares in the Osasco plant more than 25 years ago. He declined to comment on the ex-workers’ allegations but noted that “Stephan Schmidheiny himself worked as a trainee in the Brazilian Eternit under the same working conditions as the other employees.”

Giannasi has little sympathy for Schmidheiny, who claims on his own website that he was “dangerously exposed to asbestos fibers during my training period in Brazil.” Her disgust with the running of the Osasco plant motivated her to co-found ABREA. She continues to attend its monthly meetings, keeping the ailing members and their families apprised of developments in the asbestos wars. They seem to relish her stories: She’s held up asbestos shipments at ports and on highways and barged into businesses suspected of illegally selling asbestos products. She’s received death threats and been sued by the asbestos industry. For a time she was exiled to a tiny office at the Labor Ministry with no computer, no telephone and no responsibilities. She routinely defies her bosses, who view her as a headline-seeking provocateur; they’ve restricted her inspection activities to São Paulo state even though she is a federal official. “Every day is a problem,” Giannasi says.

The Brazilian asbestos industry has proved to be a fierce opponent. SAMA, which operates the Cana Brava mine in Goiás, and Eternit S.A., which operates four plants that make asbestos and non-asbestos roof sheets and other products, collectively gave more than 2 million reais (US$1.1 million) to federal, state, and local candidates from 2002 to 2008, records show. “They have many tentacles, like an octopus,” Giannasi says. Only four of Brazil’s 26 states, including São Paulo, have enacted asbestos bans. Asked about Giannasi’s campaign, a SAMA official addressed only the company’s own processes, saying fiber levels at the mine are “20 times lower than what the law requires” and that “workers have no physical contact with the mineral.”A spokeswoman for Eternit S.A., which has no connection to the Swiss Eternit Group, declined to comment.

Giannasi vs. Asbestos, Inc.

Raised during Brazil’s right-wing military dictatorship in the 1960s, Giannasi recalls hearing the screams of accused subversives being tortured at the army headquarters across from her family’s house in northeastern São Paulo state. The repression that defined that era and the progressive leanings of her parents, both public school teachers, steered Giannasi to her eventual role as an advocate for workers with asbestos-related diseases, whom she compares to genocide victims. She made her first visit to the Eternit plant in Osasco in 1986, judging its hygiene to be poor and its medical records inadequate. By 1991 she had inspected hundreds of other dusty plants and concluded that controlled use of asbestos was impossible. She was transferred from São Paulo to Osasco — “a place for troublemakers” — where she promptly made trouble for Eternit, halting the demolition of its factory in 1995 until a plan was in place to contain decades of asbestos waste. By 1998 she was a nationally known activist, referring to the asbestos industry as a “mafia” and accusing it of “blackmailing” sick workers with paltry settlement offers. Eternit sued her for defamation, but a judge threw the case out.

The years since have been marked by sporadic conflicts with the industry and her own ministry, and disappointment with the administration of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a former union leader. Asbestos production in Brazil fell during the early 1990s and then gradually increased until 2002, when Lula was elected. In the years since, production has accelerated. Giannasi made her displeasure known and in early 2004 was stripped of her inspection duties for 45 days. Her authority was restored only after she went to the press, she says. Giannasi today seems close to exhaustion, her frenetic pace unsustainable. Her ultimate aim — a federal ban on asbestos — appears out of reach.

Still, “the situation here would be far worse if she wasn’t working on it,” says Dr. Eduardo Algranti, chief of the division of medicine at Fundacentro, a São Paulo foundation that helps sick workers. “She’s very tough, very consistent in her actions. She’s absolutely committed.”

“A Mesothelioma Time Bomb"

Dr. Ubiratan de Paula Santos, a pulmonologist at the University of São Paulo Medical School, says he sees about 20 cases of mesothelioma a year, a number that has been slowly climbing. Most, but not all, of his patients were asbestos workers; one woman developed mesothelioma after sanding and painting her asbestos tile roof for Christmas over a period of years. “It’s not important how intense the exposure is,” de Paula Santos says. “Some people were exposed only for one month.” On average, victims survive 12 to 16 months after diagnosis, enduring extreme pain and the terrible knowledge that their condition is incurable. “They know they have their necks in the guillotine,” the doctor says.

It’s for these people that Giannasi forges ahead. Last fall she allowed an ICIJ reporter to accompany her and a colleague, Antonio Carlos Rodrigues Pimentel, on surprise inspections of two gasket shops in São Paulo alleged to be selling asbestos products in violation of state law. At the first shop, on the northern fringe of the city, she and Pimentel were met by a scowling, pot-bellied man who tried to deny them entry. Giannasi held up her government badge and demanded to be buzzed in.

It’s for these people that Giannasi forges ahead. Last fall she allowed an ICIJ reporter to accompany her and a colleague, Antonio Carlos Rodrigues Pimentel, on surprise inspections of two gasket shops in São Paulo alleged to be selling asbestos products in violation of state law. At the first shop, on the northern fringe of the city, she and Pimentel were met by a scowling, pot-bellied man who tried to deny them entry. Giannasi held up her government badge and demanded to be buzzed in.

Once admitted, she and Pimentel quickly found asbestos gaskets scattered among the shop’s inventory. Defiant at first, the shop’s owner grew deferential when Giannasi threatened to close the place unless every shred of the toxic mineral was thrown out. The owner promised to comply and ordered her workers to begin rounding up the prohibited items. “They all follow the same script: ‘We don’t use asbestos, we disposed of it.’” Giannasi says. “You always find something.”

Four days earlier, Giannasi had traveled in an unofficial capacity with Pimentel and Kazan-Allen, the anti-asbestos activist, to Poços de Caldas, a city in the mountains about 150 miles north of São Paulo. The American aluminum giant Alcoa, which has operated a plant there since 1970, had just been hit with its first mesothelioma lawsuit in Brazil, filed by a 58-year-old former employee. The case had caused something of a scandal in the company town, but Giannasi saw it as an opportunity to take her message to a new audience in Minas Gerais, a state in which she is forbidden to inspect. Having contacted the local media, she appeared at the town hall on a Friday afternoon and gave her standard presentation with evangelical fervor, showing slides of dying cancer victims, handing out brochures on the dangers of asbestos, and conducting an impromptu hallway news conference. Kazan-Allen stepped up to the microphone and warned that “Brazil is at the beginning of a very big curve. A mesothelioma time bomb is about to go off.”

That evening, Giannasi visited the former Alcoa worker, Dante Untura, at his home. Untura had performed maintenance at the factory, which makes aluminum powder, ingots and other items, from 1970 to 1987. He had cut and drilled sheets of Marinite insulation, which likely contained brown asbestos and was made in the United States by Johns Manville Corp. “We had no masks,” Untura said. He was diagnosed with mesothelioma in August 2009; after this, he said, “Everything changed. I lost track of life. There’s no more color. It’s all gray.”

On this warm night in mid-November, Untura did not look especially ill or seem to be in pain.His house wasdecorated for Christmas. His partner and stepdaughter served coffee and cake and tried hard to pretend that nothing was wrong. Untura became emotional only when discussing his family; it was for them, he said, that he had sued Alcoa in Brazil and was planning to sue in an American court.

The U.S. case was filed on Jan. 20. Seventeen days later, Untura was dead. Alcoa declined to comment on his lawsuit.