GREENWASHING

As new EU law looms, researchers find many ‘green labels’ fall short of sustainability promises

For decades, businesses have promoted their sustainability credentials based on voluntary certifications, but a new study identified gaps in such schemes, including some that previously came under scrutiny from ICIJ.

Voluntary certifications used by companies to tout their green credentials are not fully in line with a new European Union law banning the trade of goods linked to forest destruction, according to a new academic study.

Producers and traders of timber, palm oil and other forestry or agricultural commodities often use so-called green labels to show customers and shareholders that their operations and products do not harm the environment or violate human rights.

However, a study recently published in the Forest Policy and Economics journal found that some sustainability certification schemes awarding such labels “fell short in providing a comprehensive prohibition of deforestation and forest degradation.” The study cautioned companies not to rely on the schemes to prove compliance with the upcoming EU Deforestation Regulation.

The EUDR will go into effect at the end of 2024, requiring most European companies importing certain commodities to be able to prove the products did not originate from deforested land or contribute to forest degradation.

As part of the study, researchers at the University of Padova, in Italy, compared the requirements imposed by the new law with the standards five organizations used to certify the sustainability of timber, soy, palm oil, coffee, rubber and cocoa. Their study did not cover beef because there is no related voluntary certification scheme, the researchers said.

The EUDR makes clear that voluntary sustainability certifications are not mandatory nor sufficient to prove compliance.

Some trade organizations have urged lawmakers to recognize the schemes but the study raises questions about the industry’s position, likening the green labels to “marketing tools” that should be used in tandem with stricter legal requirements.

The “voluntary initiatives can provide on-the-ground information periodically assessed by an independent third party” and “facilitate the implementation of the EUDR,” the study said, but companies “must be cautious when incorporating these schemes into their due diligence systems.”

For instance, the researchers found that certification organizations don’t require companies to precisely geolocate the land where commodities originate from, allow deforestation and conversion of natural forests in some cases, and are lenient toward companies that violate voluntary standards.

“The evidence collected suggests that conducting deforestation, forest degradation, or non-compliance with legislation, does not result in certificate suspension, cancelation [or] withdraw,” the study said.

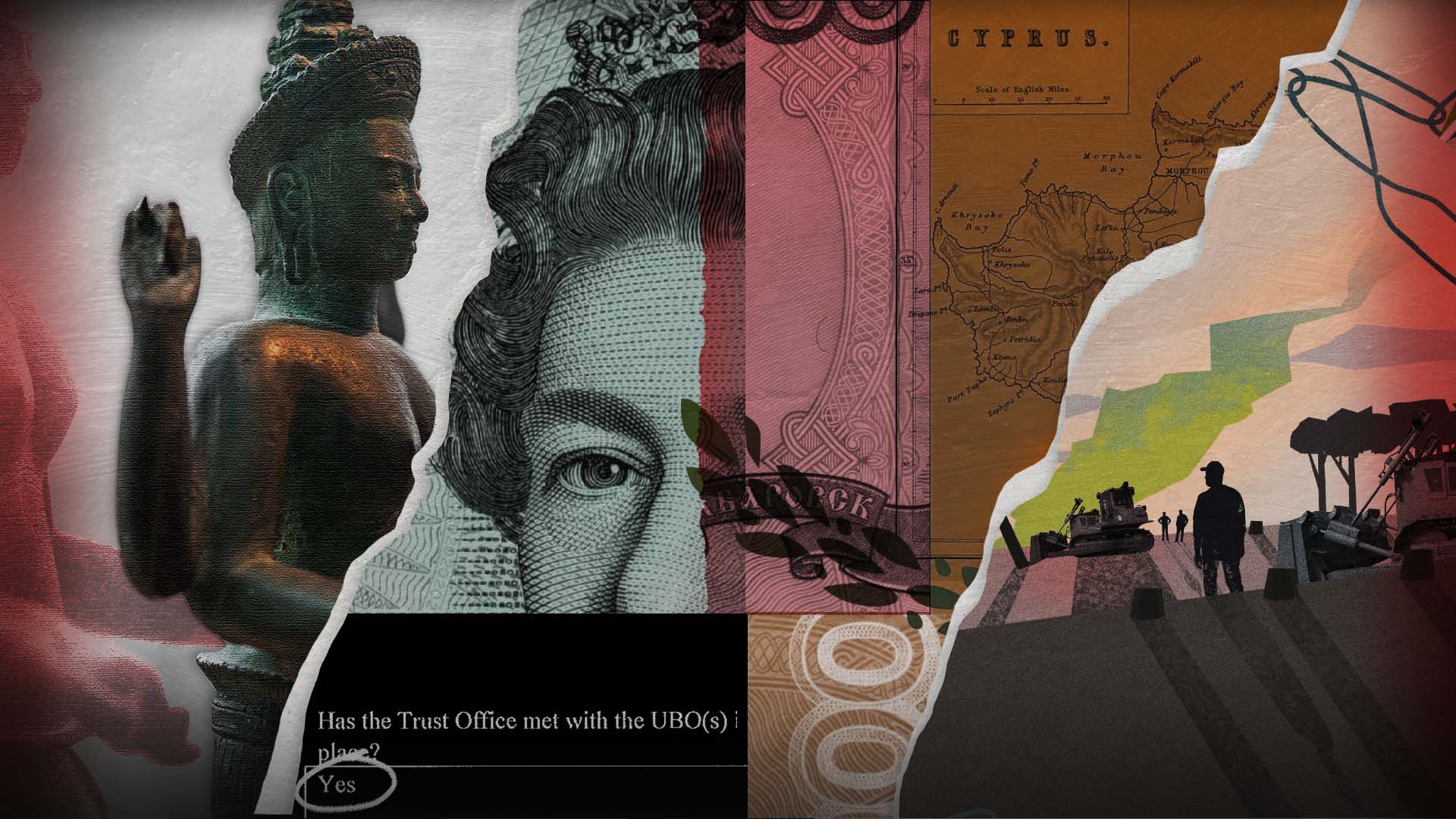

The researchers’ findings add to reporting by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and others exposing flaws in a lightly regulated sustainability industry that overlooks environmental harm and human rights violations when granting sustainability certifications.

In 2023, ICIJ’s Deforestation Inc. investigation revealed that certification firms frequently validate products linked to deforestation, logging in conflict zones and other abuses. Certification helped the firms’ clients produce and promote teak yacht decks, high-end furniture and other products in markets around the world.

An ICIJ analysis of records in at least 50 countries showed that, since 1998, more than 340 certified companies in the forest products industry were accused of environmental crimes or other wrongdoing by local communities, environmental groups, and government agencies, among others. About 50 of those firms held sustainability certificates at the time they were fined or convicted by a government agency.

‘Responsibility to keep their promises’

The researchers examined five well-known voluntary certification schemes including Forest Stewardship Council for wood, Rainforest Alliance for cocoa and coffee, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, and others. They then analyzed whether the schemes required products to be deforestation-free and have traceable supply chains, as well as whether the schemes themselves were transparent about their methods of certification and enforcement.

Mauro Masiero, one of the authors of the study, told ICIJ that he found it “surprising” that, with the exception of the FSC, most of the schemes examined in the study have some flaws in monitoring the way non-certified materials enter the supply chain of certified products.

The researchers found that “there is an inherent risk that products managed under such traceability systems are associated with deforestation and non-compliance with legislation.”

The EU law requires national authorities to conduct regular checks and act swiftly against companies that don’t comply; penalties include fines of at least 4% of a company’s annual turnover.

According to Masiero, effective enforcement of the regulation will be key to its success. Though sustainability certifications remain voluntary, he said that national authorities in some EU states may still view the certifications as indicators of compliance with the law. Masiero noted there were previoulsy “disparities” in the way the old European timber regulation was implemented across countries, with some having less strict controls than others.

Voluntary forest certification organizations, such as the FSC, were founded in the 1990s after environmentalists and regulators failed to agree on an international legal framework for forest conservation. Since then, more than a dozen such organizations and many affiliated programs have been established around the world — each with its own criteria and label.

Experts say that in countries where deforestation is widespread and forestry governance is weak, such as Brazil, voluntary certification can be a better alternative to poorly enforced laws on forest management and supply chains.

However, as more brands became willing to pay for green certifications, some organizations relaxed their standards, and the process became less effective, auditors and forestry experts told ICIJ.

According to Earthsight, an international environmental charity that has long warned about the flaws in the sustainability certification sector, the University of Padova study the first independent examination of “the interplay between these schemes and the EUDR.”

Voluntary certification schemes should not be taken as gospel, Masiero said. “We are aware that there may be mistakes or conditions that can be improved. It is important to acknowledge that and intervene whenever possible,” he said.

The researchers acknowledged that some certification organizations were seeking to change their standards to align with the new EU law, and said that the study will continue.

Masiero warned that consumers should be aware of what green labels mean as well as their limitations. “At the same time, these labels have the responsibility to keep their promises,” he said.