Telecom giant Ericsson sought permission from the terrorist group known as the Islamic State to work in an ISIS-controlled city and paid to smuggle equipment into ISIS areas on a route known as the “Speedway,” according to a leaked internal investigation report obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

The report reveals that the Swedish-based firm made tens of millions of dollars in suspicious payments over nearly a decade to sustain its business in Iraq, financing slush funds, trips abroad for defense officials and payoffs through middlemen to corporate executives and possibly terrorists.

The internal investigation describes a pattern of bribery and corruption so widespread, and company oversight so weak, that millions of dollars in payments couldn’t be accounted for – all while Ericsson worked to maintain and expand vital cellular networks in one of the most corrupt countries in the world. The review, which has not been made public, covers the years 2011 to 2019.

Ericsson’s business in Iraq relied on politically connected fixers and unvetted subcontractors. It was marked by sham contracts, inflated invoices, falsified financial statements and payments to “consultants” with nebulous job descriptions. In one instance, a member of a powerful Kurdish family, the Barzanis, collected $1.2 million for “facilitation to the chairman” of a mobile phone operator — also a Barzani, the report says.

Most of the corrupt conduct came after Ericsson, a key actor in the West’s battle with China over the future of global communications, acknowledged in 2013 that it was cooperating with U.S. authorities investigating bribery allegations elsewhere. The U.S. probe resulted in a $1 billion bribery settlement in 2019 with the U.S. Justice Department and the Securities and Exchange Commission. The settlement does not mention Iraq.

ICIJ shared the leaked records with The Washington Post, SVT in Sweden and 28 other media partners in 22 countries as part of a project known as the Ericsson List. ICIJ and its partners verified the records’ authenticity and spent months examining other documents and interviewing ex-employees, government officials, contractors and other industry insiders in Iraq, London, Washington, Jordan, Lebanon and elsewhere.

The leaked documents include 73 pages of a 79-page report on Ericsson’s Iraq business, including summaries of 28 witness interviews and 22.5 million emails.

ICIJ and partnering news organizations sent detailed questions to Ericsson about the secret internal review. Instead of answering, Ericsson issued a public statement on Feb. 15 acknowledging “corruption-related misconduct” in Iraq and possible payments to ISIS.

Ericsson CEO Börje Ekholm also granted interviews to news outlets not in possession of the leaked documents. He said that Ericsson may have made illicit payments, but that the company had often struggled to identify the final beneficiary.

“We can’t determine where money sometimes really goes, but we can see that it has disappeared,” Ekholm told a Swedish newspaper.

Ericsson cited its “commitment to transparency” in its recent disclosures. But the company made no mention of other internal probes described in the leaked documents.

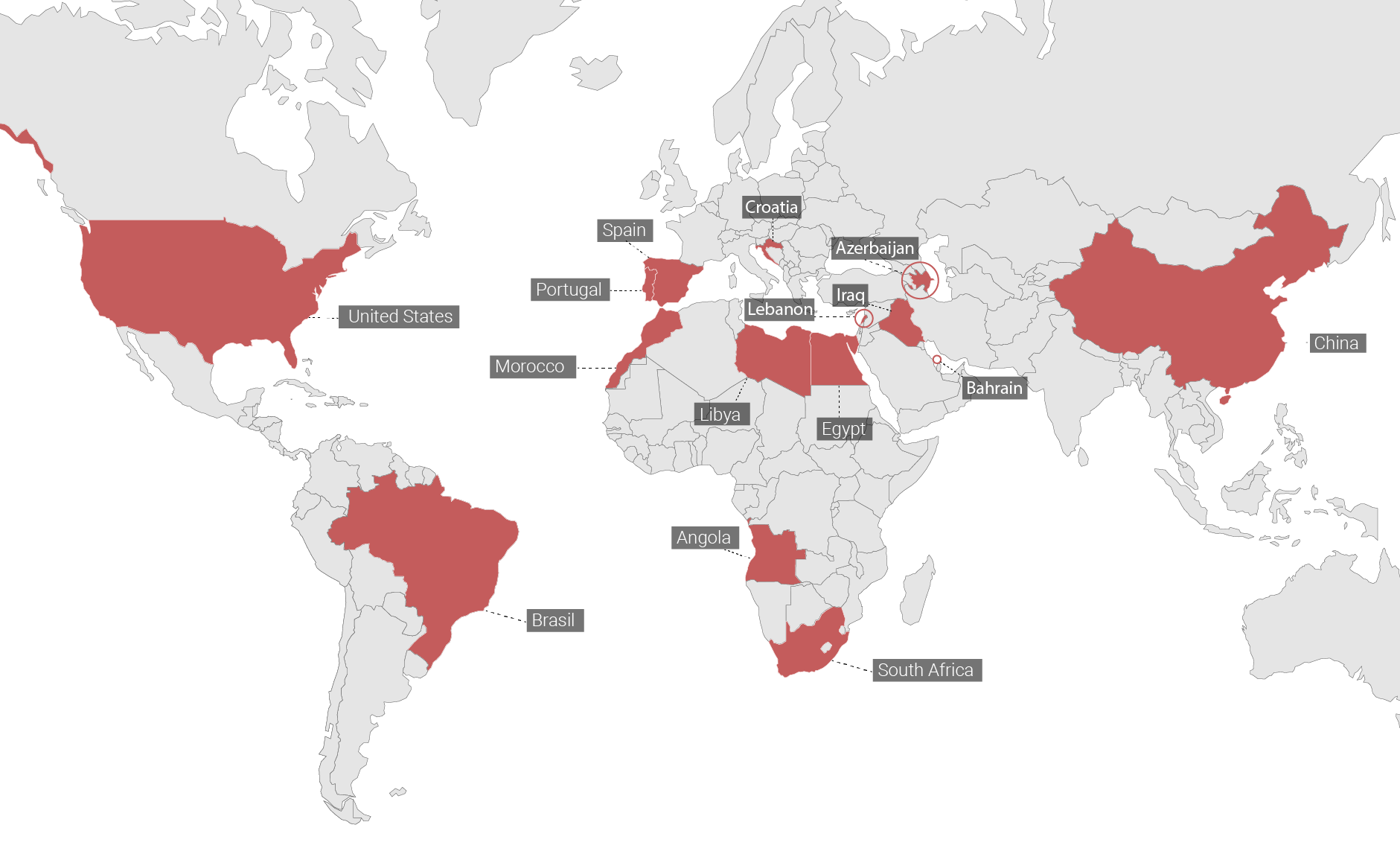

The records show that besides Iraq, the company examined alleged misconduct in Lebanon, Spain, Portugal and Egypt. In addition, a spreadsheet lists company probes into possible bribery, money laundering and embezzlement by employees in Angola, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brazil, China, Croatia, Libya, Morocco, the United States and South Africa. These probes have not been previously disclosed.

A 2014 decision stands as pivotal for Ericsson in Iraq. As ISIS conquered towns, pillaged homes and beheaded hostages, two employees proposed halting operations in Mosul and elsewhere in the country. Senior regional executives rejected the recommendation. Leaving would “destroy our business,” the report quotes the executives as saying.

Less than a month later, Ericsson asked a regional partner, Asiacell Communications, to seek “permission from ‘local authority ISIS’” to continue work in Mosul, leading to gun-toting ISIS fighters kidnapping a crew chief with an Ericsson subcontractor, according to the report and the kidnap victim. Asiacell didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment.

Ericsson’s investigators said they could not rule out the possibility that the company financed terrorism through its subcontractors, though they couldn’t identify any Ericsson employee as “directly involved.”

Ericsson’s compliance department, which monitors the transnational company’s activities, prepared the confidential records with the help of Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, a high-powered New York law firm, which handled its defense in the U.S. bribery probe.

The internal review, while damning, often fails to reach specific conclusions and suggests an incomplete investigation into some of the most explosive allegations, including that payments were made to terrorists. Internal investigators didn’t interview officials of either the main transport firm moving Ericsson equipment through ISIS territory or the subcontractors the company relied on to work in ISIS-held Mosul, for example.

Questions from ICIJ and its partners that Ericsson has refused to address include why a regional executive was promoted during the corruption probe and why workers’ lives were put at risk by company operations in Iraq.

It is not clear how much the U.S. Justice Department and Securities and Exchange Commission knew about abuses in Iraq or whether Ericsson fully disclosed its internal findings to the agencies. The Justice Department and SEC declined to comment on any aspect of the Ericsson case. Simpson Thacher did not respond to requests for comment.

Ekholm told Reuters the 2019 settlement “limits our ability to comment on what is disclosed or not disclosed.”

He said the company chose not to disclose the Iraq probe because “the materiality of our findings did not pass our threshold to make a disclosure.”

Ericsson’s share value plunged $4.4 billion, or more than 10%, the day after Ekholm’s admission that the company might have paid ISIS.

Law firms soon began to solicit Ericsson investors for a possible lawsuit alleging that the company withheld “material information” about possible payments to militants.

In a news release, the company said that it was “committed to conducting business in a responsible manner, applying ethical standards in anti-corruption, humanitarian and human rights terms.”

‘Bribes, kickbacks and embezzlement’

The internal report alleges that at least 10 current and former employees violated Ericsson’s ethics code. Among the “breaches” identified by the report were bribery, fraud, money laundering and obstruction of the investigation.

Ericsson showered clients with artwork, clothes and other perks like iPads, watches and Mont Blanc pens, the report says. It paid for trips to Spain and Sweden for 10 Iraqi defense ministry officials.

In its recent news release, Ericsson said that it had taken disciplinary actions and that several employees had left the company as a result of the investigation. But other employees implicated in misconduct remain at Ericsson. At least one was promoted.

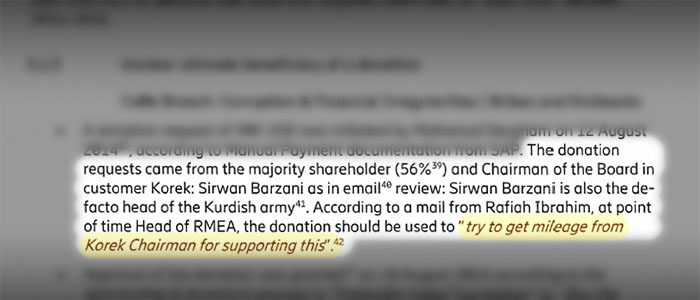

Investigators found that Elie Moubarak, Ericsson’s account manager for Korek Telecom, a mobile phone carrier and the company’s largest customer in Iraq, engaged in “corruption and financial irregularities.”

In one instance, Moubarak asked for a $50,000 “donation” to Kurdistan’s Peshmerga forces “for fighting ISIS,” the report says. The militia was led by Sirwan Barzani, also a major shareholder of Korek and board chairman at the time. The official request indicated that the donation was to benefit refugees and displaced children in Kurdistan, the report says.

Rafiah Ibrahim, the company executive in charge of the Middle East and Africa, endorsed the donation to “try to get mileage from the Korek chairman,” the report says. Ericsson funneled the money through a charitable group. Internal investigators couldn’t identify the ultimate beneficiaries.

Ibrahim was named a senior vice president and member of the executive team under Ekholm in 2017, and she became an adviser to Ekholm in 2019. Moubarak was promoted to country manager of Iraq in 2019. Neither Ibrahim nor Moubarak responded to requests for comment.

A business vulnerable to bribery

Ericsson’s problems in Iraq illustrate the risk of corruption in the $1.6 trillion telecom industry. Large profits can flow from government licenses and telecom equipment contracts, and anti-bribery enforcement is weak. Conducting business in Iraq “may in itself pose significant political, financial and legal risks and requires diligent controls,” the internal review says.

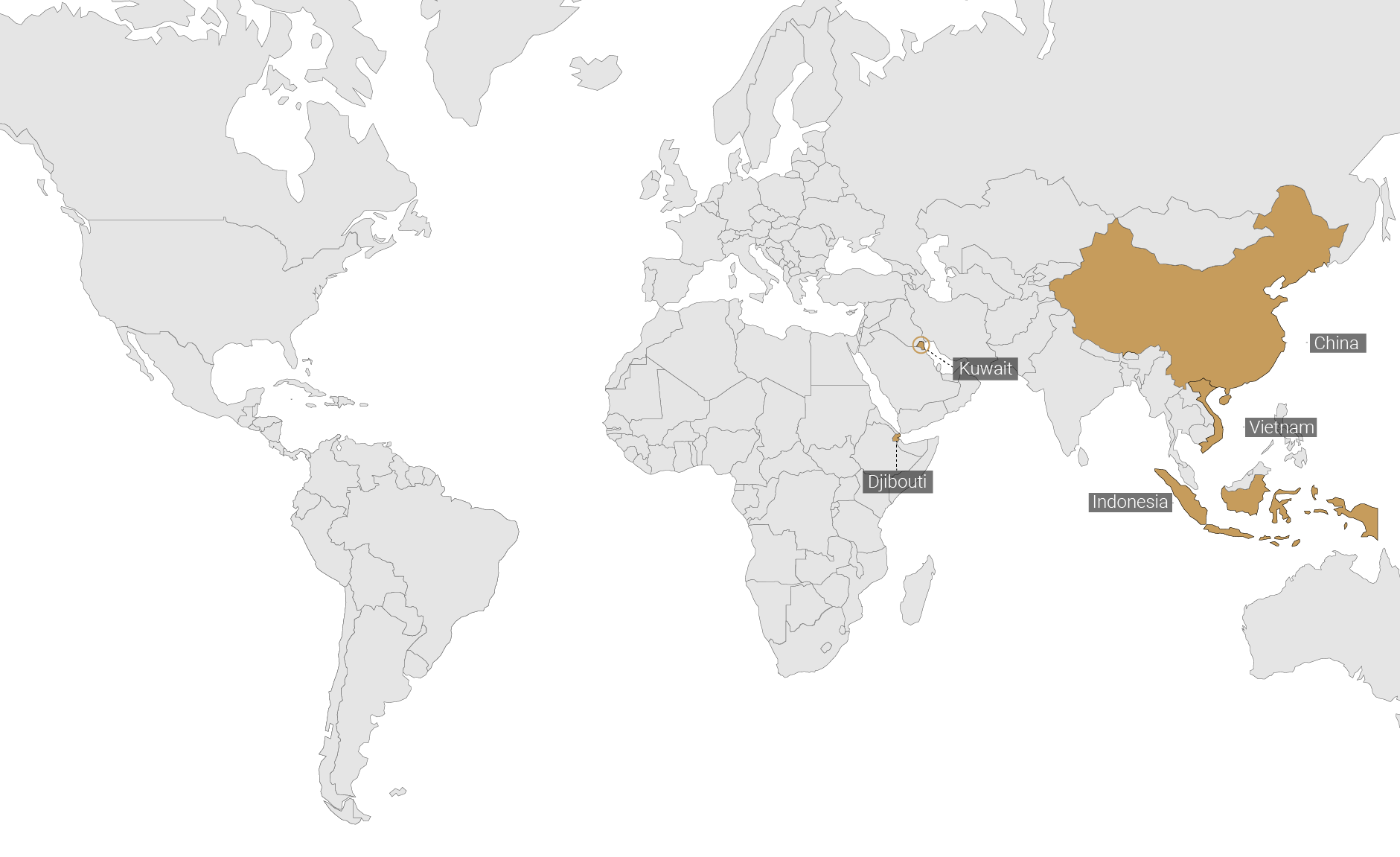

The investigation also calls attention to the Justice Department’s handling of corporate crime. The billion-dollar settlement with Ericsson in 2019 was one of the largest ever, and the company admitted to engaging in bribery and other misconduct in Djibouti, China, Vietnam, Indonesia and Kuwait from 2000 to 2016.

Under the deal, known as a deferred prosecution agreement, Ericsson avoided a criminal trial, and none of its top executives were held accountable. The U.S. government reserves the right to bring charges if it decides that Ericsson hasn’t lived up to the terms of the deal, including disclosing allegations of wrongdoing.

Critics say such deals, negotiated by prosecutors and corporate defense lawyers behind closed doors, protect top executives from criminal prosecution and do not provide effective punishment. Innocent shareholders suffer, they say, instead of guilty executives.

In October, Ericsson said it received notice from the Justice Department that it had violated its plea deal “by failing to provide certain documents and factual information.” Ekholm told a Swedish newspaper that the violation wasn’t related to Iraq.

Local start, global battleground

Officially known as Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson, the company generates annual revenue of $25 billion and has roughly 100,000 employees in more than 140 countries. It is a leading supplier of towers, radio base stations and mobile switching centers — the foundation of modern communications.

Ericsson traces its origins to 1876, when Lars Magnus Ericsson, a farmer’s son, opened a telegraph repair shop in Stockholm. The company went on to pioneer automated telephone switching, international calling, mobile telephones and, in the 1990s, the mobile internet.

After a string of corporate scandals and bad business bets in the 2000s, Western telecom companies, including Ericsson, lost ground to new Chinese equipment giants, including Huawei Technologies Co.

Ericsson tried to keep up by outsourcing work to local sales agents and other middlemen, distancing itself from the sometimes dirty business of securing contracts and doing business in developing countries. In the case that led to the 2019 settlement, the U.S. described slush funds, inflated costs, false invoices, rigged bidding, unvetted middlemen and bribery in five countries — the same pattern of behavior the internal review describes in Iraq.

In 2010, Hans Vestberg, a longtime Ericsson manager, became the company’s chief executive. Vestberg left in 2016 amid corruption investigations into the company and was replaced by the current chief executive, Börje Ekholm.

The U.S. has favored Western mobile companies in their rivalry with Huawei, warning that the Chinese company’s links to the Communist Party make it a national security threat. The race for dominance in the next generation of mobile communications, known as 5G, has raised the stakes. An adversary in control of the network could shut down vital systems during times of conflict, U.S. officials say.

In 2020, two months after Ericsson’s corruption settlement, then-U.S. Attorney General William Barr gave an unusual speech in which he suggested that the U.S. government consider buying a stake in Ericsson or another Western telecom firm, Nokia. He did not mention the Ericsson case.

With contracts in many developed countries locked up, the battleground for global dominance is playing out in the Middle East, Africa and other fast-growing markets.

Ericsson has been a presence in Iraq since the 1960s when it helped install a telephone system in Baghdad. The dictator, Saddam Hussein, restricted possession of mobile phones to a tiny elite. After the U.S. invasion in 2003, Iraq emerged as one of the world’s few virgin mobile phone markets.

Ericsson won lucrative post-Iraq War contracts to supply the state-run Iraq Telecommunication and Post Co. with new technology. Ericsson also won contracts to supply towers and to upgrade equipment and networks for Iraq’s three main mobile operators: Asiacell, a Qatari-owned firm; Zain Iraq, part of a Kuwaiti telecom group; and Korek, controlled by Sirwan Barzani, who is also a nephew of the former president of Iraq’s semiautonomous Kurdistan region.

Ericsson sales in Iraq totaled about $1.9 billion from 2011 to 2018, the internal report says.

The Barzanis are a family of Kurdish oligarchs, and the U.S. considers them top allies in the fight against ISIS. The internal report details several suspect transactions between Ericsson and members of the family. In one deal, the report says, Rasech Barzani, had “no clear role” as a consultant who collected $1.2 million for offering “business intelligence and facilitation to the chairman of Korek.”

Ericsson’s report shows that Korek evaded taxes and fees amounting to $375 million and threatened to “demolish rival company towers in Kurdish territory.”

Rasech Barzani did not respond to requests for comment. Sirwan Barzani didn’t respond to questions about Korek’s relationship with Ericsson. In a statement, a spokesman emphasized Barzani’s history of fighting ISIS, also known as Daesh.

“After Daesh took Mosul in 2014, Sirwan Barzani rejoined the Peshmerga — stepping back from Korek — to return to the frontline to defend his country and the Western world from the threat that Daesh posed,” the spokesman said.

‘Close ties pull strings’

As Ericsson’s sales agent, Jawhar Surchi helped the company navigate Iraq’s bureaucracy for 15 years. Through his firm, Al-Awsat Telecommunication Services, Surchi secured contracts for Ericsson with government agencies and the mobile operators Asiacell and Zain.

Surchi told internal investigators that his “close ties” to people in power allowed him to “pull strings” for Ericsson and that he did “many favors” for the company, helping it win contracts in “extreme times.” Ericsson couldn’t have succeeded in Iraq without his company, Surchi said.

Al-Awsat, which means “the middle” in Arabic, was a conduit for tens of millions of dollars in suspicious payments, the internal review found. Among these: $10.5 million to an Al-Awsat-linked company, where the ultimate beneficiary could not be identified; and $27 million for consultancy services, for which investigators found “deficient proof of work.” An audit showed that most of the money went to Surchi’s personal account in Jordan.

According to the report, Al-Awsat also secretly paid for air fares for executives at Iraq’s state-owned telephone company. Al-Awsat steered work to firms owned by family members and friends, the report says.

Ericsson empowered Al-Awsat to sign contracts on its behalf.

The report says Surchi’s firm over time came to be known simply as “Ericsson.”

Two senior employees told investigators that Ericsson directed $500,000 in “commission” payments through Al-Awsat to Asiacell’s chief executive to win a network upgrade contract known as the Peroza Project. The project included replacing and expanding Asiacell’s network, assembling telecom towers in a warehouse, testing them and sending them to be installed across Iraq.

The report says Ericsson’s top Iraq executive, Tarek Saadi, approved the payment, which was routed through Al-Awsat using two sham purchase orders, each for $250,000, marked as for “security services.” The report calls the Peroza Project bidding a “manipulated” selection process.

Saadi, an American-educated engineer, pushed his staff to issue purchase orders to Al-Awsat every month, “regardless of whether there were deliveries ongoing or not,” the report says.

Saadi declined to comment, referring questions to Ericsson, which he left in 2017. He became an adviser to Korek.

In two interviews with ICIJ partner The Washington Post, Surchi acknowledged that his extensive political connections helped foreign companies compete in Iraq. “My strength was, I knew the people, knew all the prime ministers,” he said, and he listed the prime ministers by name.

He denied winning contracts through bribery or engaging in any sort of corruption, and he said he never saw Ericsson do so. Of the allegations, he said, “Somebody is trying to discredit” the company. “Whatever is said is from jealousy.’’

A new problem: The rise of ISIS

In 2013, Ericsson acknowledged that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission had opened an investigation into its business practices in Romania. A former Ericsson executive had alleged that the company used a slush fund to win contracts there by paying off officials. Over time, the investigation broadened to include other countries, attracting the attention of the Justice Department, which joined the probe two years later.

Ericsson hired the Simpson Thacher law firm to monitor the company’s internal corruption investigations. The legal team was composed of three former U.S. officials, including Cheryl Scarboro, who previously served as chief of the SEC’s anti-bribery unit.

According to Swedish court records, the law firm told U.S. prosecutors about a whistleblower’s allegations that Ericsson may have improperly paid more than $2 million to win a contract also sought by Huawei in Djibouti, in the Horn of Africa. As the investigation progressed, Ericsson’s attorneys also provided a list of the company’s outside consultants in 10 countries, including Iraq, according to documents reviewed by ICIJ’s Swedish partner SVT. The documents included Ericsson contracts with Al-Awsat.

As U.S. authorities ramped up the bribery probe, Ericsson and its customers grappled with a new problem: the rise of ISIS, a terrorist group notorious for its massacres of religious and ethnic minorities, its use of chemical weapons and its public beheadings. At its peak, the group ruled more than 8 million people in parts of Iraq and Syria. It also made extensive use of mobile phone technology to spread images of beheadings and to traffic sex slaves.

Ericsson and its subcontractors kept working. The day after ISIS swept into Mosul in 2014, the company was searching for contractors to work on Asiacell’s Peroza Project upgrade, the internal report said.

Some employees thought that Iraq was becoming so unsafe that the company should invoke the so-called force majeure clause in its contracts. Force majeure would provide a legal defense if Ericsson stopped work because of events beyond the parties’ control.

Tom Nygren, then vice president and general counsel for Ericsson in the Middle East, made a “strong recommendation” to his supervisors to invoke force majeure, according to the report.

Roger Antoun, an Ericsson manager for Asiacell’s Peroza Project, said the proposal to invoke force majeure was “escalated” to the executive office. “I raised it verbally as well,” he told investigators.

Antoun would become a key figure in the internal probe after investigators determined that he had embezzled $308,000 through an “uncontrolled slush fund” set up through subcontractors. The revelation triggered a wider investigation into potential payments to terrorists.

Antoun later paid the money back. Ericsson said it fired him in January 2019. Antoun declined to comment.

Saadi, the company’s top Iraq executive, and Rafiah Ibrahim, head of the Middle East and Africa region, opposed invoking force majeure, the report says.

‘Abandoned’ to ISIS

A month after Ericsson’s decision to press ahead in Mosul, an engineer conducting tests of cell towers as part of the Peroza Project delivered a letter to an office where ISIS had set up operations, according to the engineer, who asked to be identified only by his first name, Affan. The letter from Ericsson and Asiacell sought permission from the terrorist group to continue working in the area, he said.

In interviews, the engineer, who worked for a subcontractor called Orbitel Telecommunication said the three companies insisted that work continue even after ISIS detained several of his colleagues for a time. Ericsson and his supervisor told him to deliver the letter in person, Affan said. Orbitel declined to comment.

Affan said an ISIS militant later called and summoned him to a bridge overpass, where men with scarves hiding their faces put a hood over his head, shoved him into the back seat of a Toyota pickup and took off.

One assailant, a sheikh, forced him to call a senior Ericsson manager in the northern city of Sulaymaniyah and then, shouting at the manager, threatened to blow up Ericsson’s offices, Affan said. The sheikh demanded millions of dollars “for every month we worked without ISIS notification,” Affan said.

The internal review confirmed the kidnapping, the phone call, and the demand for money.

Affan said ISIS ordered him to remain at his Mosul home until Ericsson made the payments. He said that Ericsson and the other companies abandoned him and that company employees almost immediately stopped answering his calls. A few weeks later, ISIS told him that he was free to leave his house.

Emails obtained by ICIJ’s German media partner NDR confirm several details of Affan’s account.

In an interview with internal investigators, an Ericsson manager said Asiacell “made arrangements to obtain the release of the hostage and to let Ericsson continue the work in Mosul.”

The report doesn’t say what the arrangements were.

In interviews with ICIJ and media partners NDR and Daraj, telecom employees and contractors in Iraq said it was common knowledge that before ISIS companies paid protection money to militants to prevent attacks on their equipment and to allow workers to do their jobs.

“If your business involves money, you have to pay,” Affan said. “If you don’t pay, they will come after you.”

‘The legal way or the Speedway’

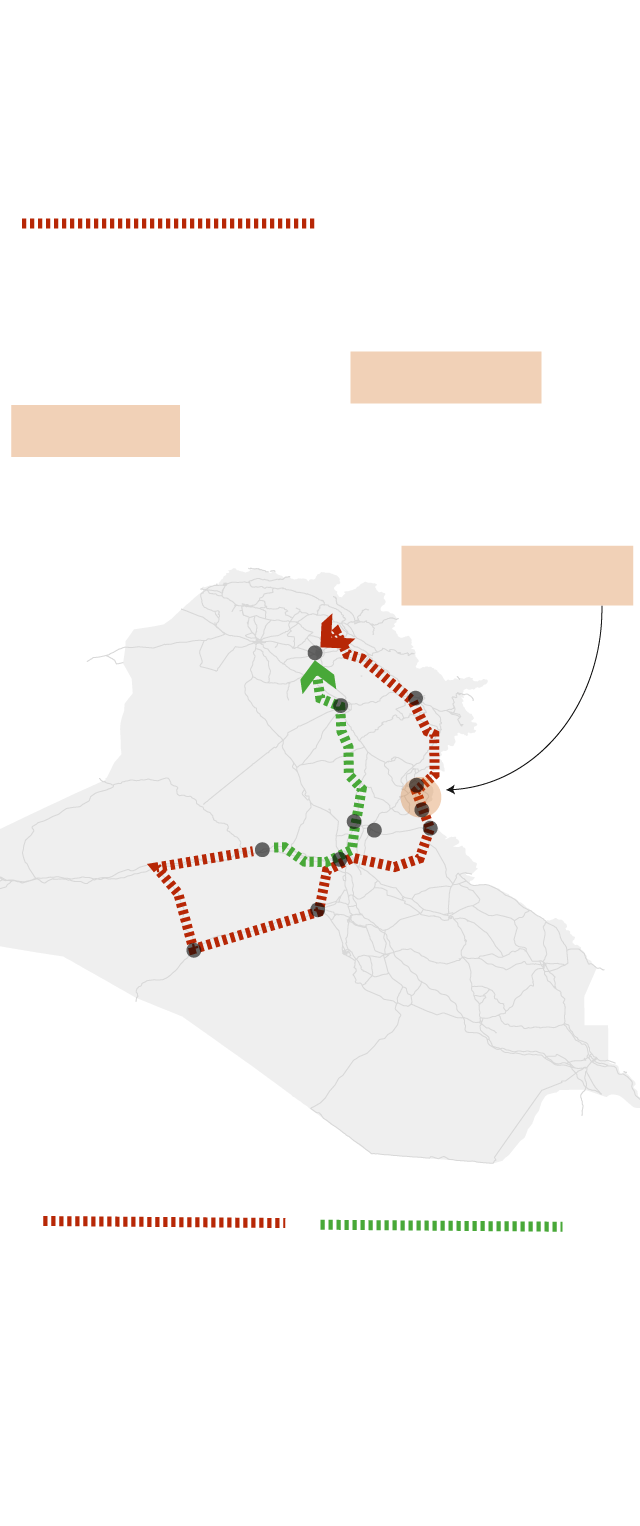

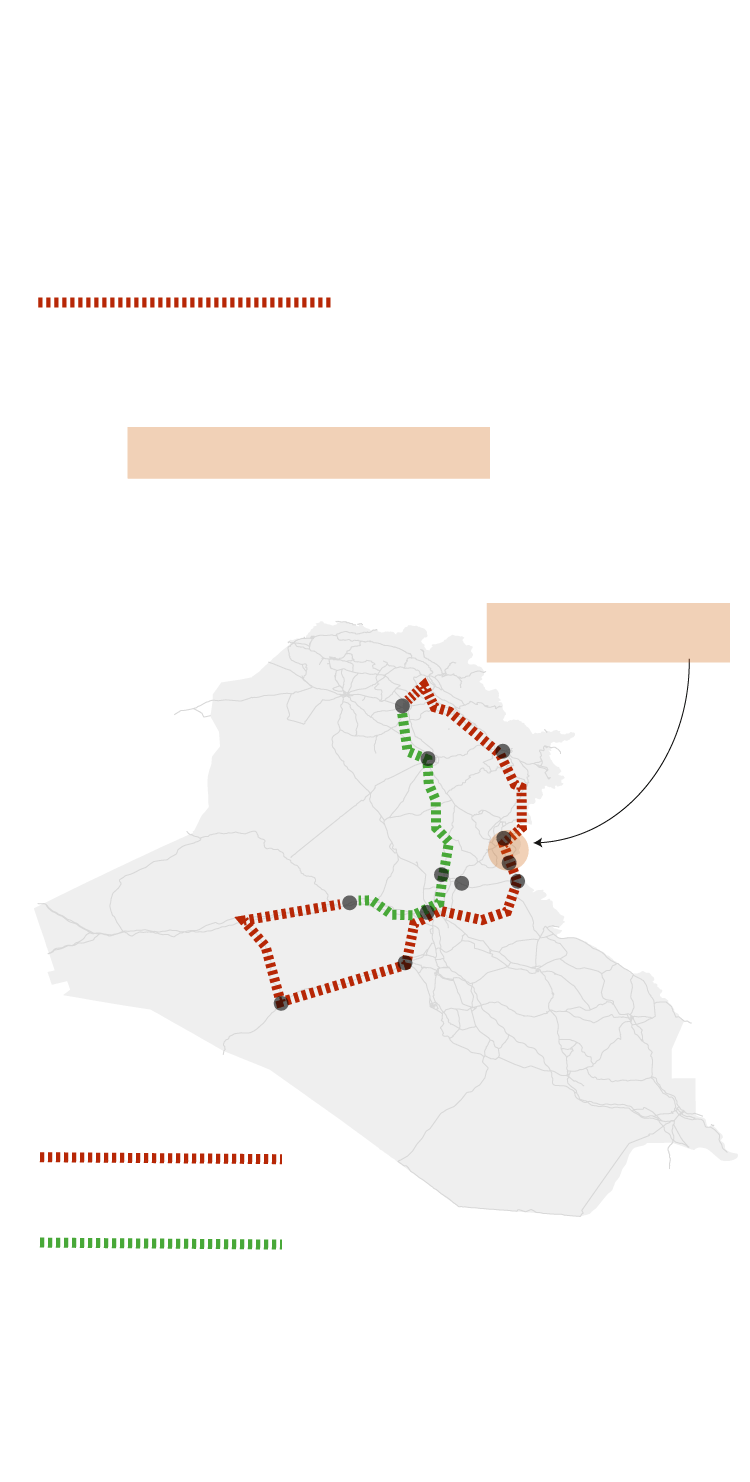

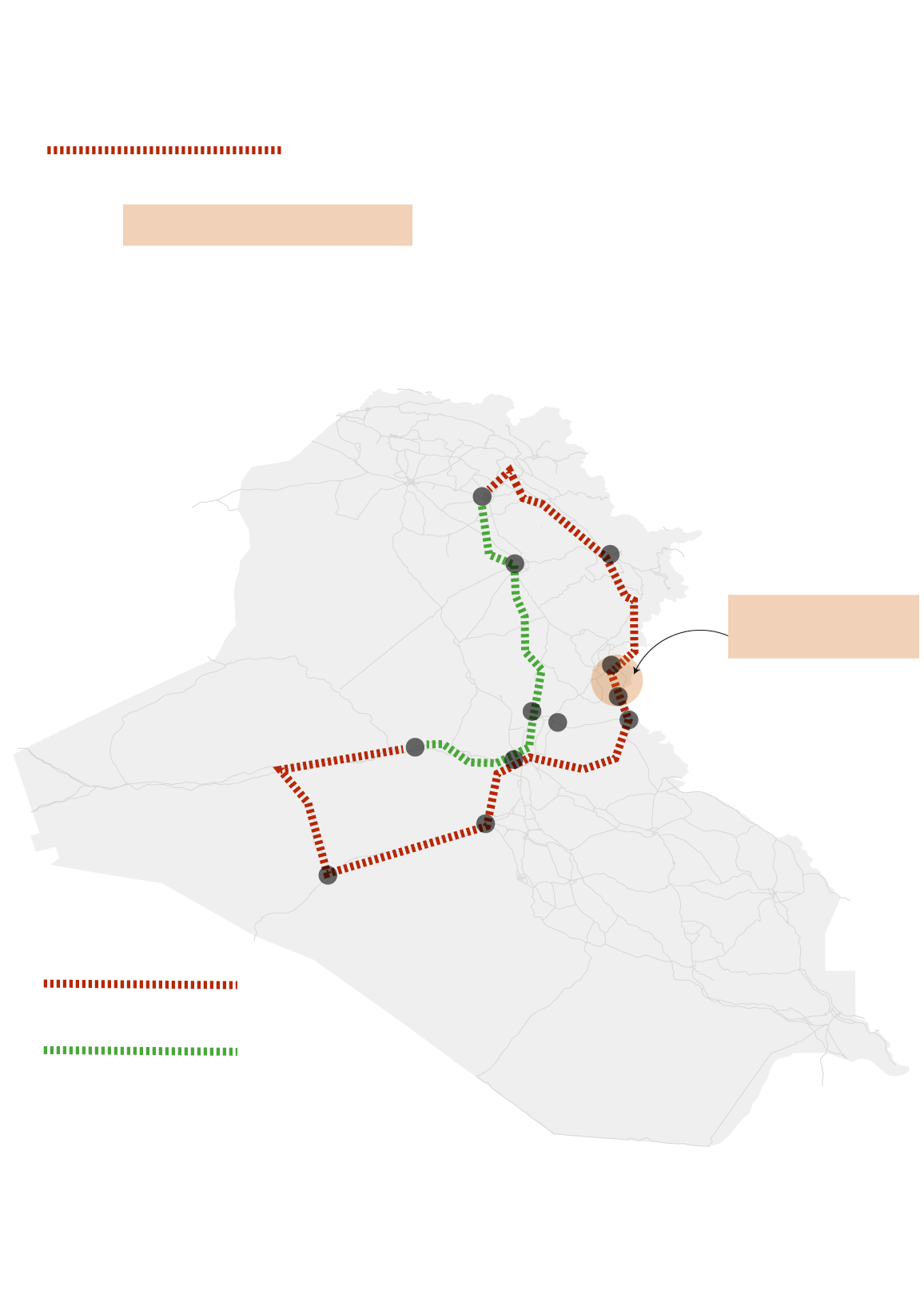

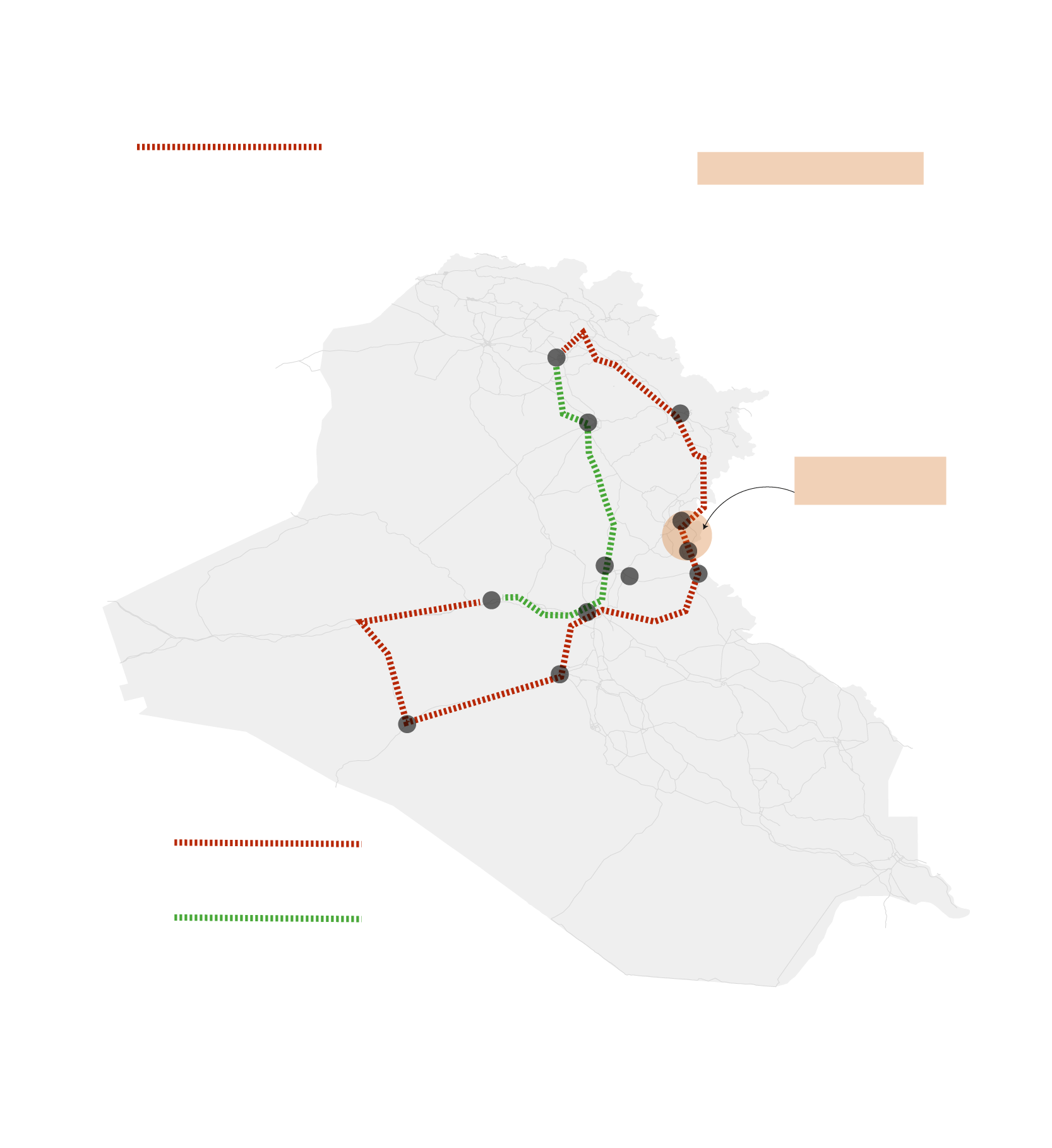

As part of the Peroza expansion, Ericsson and its partner Asiacell needed to haul cell towers and equipment from Erbil, in northern Iraq, to Ramadi, in the middle of the country. A transportation contractor, Cargo Iraq, offered two options, according to the report: the “legal way” and the “Speedway.”

The Speedway was actually longer — and more expensive — but it had the advantage of avoiding Iraqi customs checkpoints, which were often backed up for days, if not weeks.

The problem: Parts of the Speedway passed through ISIS territory.

In interviews, Iraqi truck drivers and local journalists said the route was perilous. ISIS militants set up checkpoints, attacking and kidnapping travelers to extort money along a 100-kilometer stretch, they said.

A trucker in his 40s with two children told NDR that he transported food and other commodities via the Speedway with its ISIS checkpoints. He said he once saw a man who had been fatally shot. Nearby a truck was on fire.

“The road is isolated and terrifying and not safe,” he said.

Dodging government checkpoints

An alternative route between Ramadi and Erbil avoided delays and high tariffs at government checkpoints and instead passed through some ISIS areas in 2016-2017, according to drivers and other locals interviewed by ICIJ and NDR.

ISIS checkpoints

Erbil

Sulaymaniyah

Kirkuk

Khanaqin

Naft Khana

Al Khalis

Ramadi

Mandali

Baqubah

Baghdad

Karbala

Al-Nukhib

Alternative route

Legal route

Map showing an alternative route between Erbil and Ramadi in Iraq.

Dodging government checkpoints

An alternative route between Ramadi and Erbil avoided delays and high tariffs at government checkpoints and instead passed through some ISIS areas in 2016-2017, according to drivers and other locals interviewed by ICIJ and NDR.

ISIS checkpoints

Erbil

Sulaymaniyah

Kirkuk

Khanaqin

Naft Khana

Al Khalis

Ramadi

Mandali

Baqubah

Baghdad

Karbala

Al-Nukhib

Alternative route

Legal route

Map showing an alternative route between Erbil and Ramadi in Iraq.

Dodging government checkpoints

An alternative route between Ramadi and Erbil avoided delays and high tariffs at government checkpoints and instead passed through some ISIS areas in 2016-2017, according to drivers and other locals interviewed by ICIJ and NDR.

Erbil

Sulaymaniyah

Kirkuk

ISIS checkpoints

Khanaqin

Naft Khana

Al Khalis

Ramadi

Mandali

Baqubah

Baghdad

Karbala

Al-Nukhib

Alternative route

Legal route

Map showing an alternative route between Erbil and Ramadi in Iraq.

Dodging government checkpoints

An alternative route between Ramadi and Erbil avoided delays and high tariffs at government checkpoints and instead passed through some ISIS areas in 2016-2017, according to drivers and other locals interviewed by ICIJ and NDR.

Erbil

Sulaymaniyah

Kirkuk

ISIS checkpoints

Khanaqin

Naft Khana

Al Khalis

Ramadi

Mandali

Baqubah

Baghdad

Karbala

Al-Nukhib

Alternative route

Legal route

Map showing an alternative route between Erbil and Ramadi in Iraq.

The review identified 30 trucks — mostly 40-foot rigs — that paid $3,000 to $4,000 per load to carry Ericsson equipment across areas held by ISIS and other militias. One table in the report shows that in March 2017, Ericsson paid $22,000 per truck for three loads on a single day.

“By avoiding official customs by transporting through areas controlled by militias, including ISIS, it cannot be excluded that Cargo Iraq engaged in facilitation payments (to official Customs officers), bribery and potential illicit financing of terrorism to carry out transportation operations for Ericsson,” the report says.

Bahez Abbas, owner of Cargo Iraq, denied in an interview that his company paid ISIS.

According to the report, Asiacell recommended that Ericsson hire Cargo Iraq. “Evidence suggests that Asiacell have engaged in smuggling and potential illegitimate payments directly and through Ericsson,” the report says.

‘Collateral consequences’

Ekholm and the company have cited the company’s commitment to integrity, ethical conduct and “doing business the right way.” At an earnings call in January, for example, the chief executive spoke about how the company was building a “world class compliance program” and “culture of integrity.”

Keeping wraps on an internal report describing widespread corruption appears at odds with that rhetoric, experts say. Ericsson “seems to have fallen short of its own and investors’ standards on anti-corruption,” said Joachim Nahem, a partner at The Governance Group, an Oslo based research and advisory group.

As part of the deal struck with the U.S. government in 2019, the company is obligated to be more transparent — with government officials, at least. Ericsson promised to report wrongdoing and submit to audits and to the scrutiny of an outside monitor for three years.

At the plea hearing, a prosecutor said the U.S. didn’t indict Ericsson, and allowed an Egyptian subsidiary to plead guilty instead, to avoid unspecified “collateral consequences.” Ericsson remains eligible to bid on U.S. government contracts.

Only one Ericsson employee has been charged in the U.S. case. Afework Bereket was indicted last year, charged with arranging more than $2 million in bribes to three officials to beat out Huawei in the competition for a contract in Djibouti. He remains at large. Bereket and three other former Ericsson employees face a criminal trial in Sweden on charges related to the Djibouti matter.

Ekholm said the company would continue to investigate what happened in Iraq.

Contributors: Dean Starkman, Delphine Reuter, Gerard Ryle, Fergus Shiel, Richard H.P.Sia, Emilia Díaz-Struck, Agustin Armendariz, Jelena Cosic, Ben Hallman, Karrie Kehoe, Nicole Sadek, Hala Nasreddine (Daraj, Lebanon), Greg Miller and Louisa Loveluck (Washington Post), Per Agerman and Fredrik Laurin (SVT, Sweden), Mohammed Komani (ARIJ), Benedikt Strunz and Jennifer Johnston (NDR, Germany), Joe Hillhouse, Scilla Alecci, Caroline Desprat, Tom Stites, Asraa Mustufa, Hamish Boland-Rudder, Antonio Cucho Gamboa, Whitney Awanayah, Pierre Romera.