BEHIND THE SCENES

From a global fentanyl ring to a grieving family in Garland, a reporter’s FinCEN Files diary

By investigating four names behind a mysterious $400,000 transaction, an ICIJ reporter chased dirty money flows and uncovered victims of a failed anti-money laundering system.

“Hello Will, this is Brandon Hubbard, you sent me a letter.”

The last thing I expected when reporting on the FinCEN Files investigation was a nighttime reply from a convicted drug dealer.

“Texting because this jail provides iPods to do so but if you want to set up a phone call that is fine,” Hubbard wrote me at 9:10 p.m. on July 28 from his cell in Grand Forks, North Dakota.

I had contacted Hubbard a week earlier. He was easy to find; he’s locked up for life for his role in a scheme that imported fentanyl into the U.S. He’s also a convicted money launderer.

“I’m reporting on fentanyl and how people in the USA buy it and pay for it,” I told Hubbard in my letter. “I’d really like to talk to you about what you know about how fentanyl is ordered and paid for … No worries if you don’t feel like you know much about this – anything you can tell me would be really interesting.”

I knew it was a long shot, but Hubbard had already spoken to Keegan Hamilton, a VICE journalist who aired an excellent podcast on deadly opioids. Keegan had focused on fentanyl’s route from China to the United States, where it kills tens of thousands of Americans each year.

I was interested in something else. As a reporter with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, my bread and butter is complex financial documents, bank transfers, and secretive shell companies. I was in Jerry McGuire mode: “Show me the money.”

Hubbard told me all about how he paid for fentanyl from China and through a jailed middleman in Canada and his vast cryptocurrency operation.

“That’s the first thing they asked me when they came in the door, ‘Where’s the money?’” Hubbard told me in our first interview about his recollection of the night he was arrested by the FBI.

Texting and speaking to Hubbard in two interviews was one of the most unexpected episodes in my reporting on the FinCEN Files, a global exposé of how the world’s largest banks, politicians and shadowy characters move money around the world with few constraints. BuzzFeed News obtained thousands of secretive bank documents from the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, the financial crimes watchdog agency known as FinCEN inside the U.S. Department of Treasury. BuzzFeed News shared the documents with ICIJ and we gathered a world-class team of more than 400 journalists. For over 16 months, reporters traced how dirty money flows freely through major banks, swamping a broken enforcement system. They are the kind of documents that no journalist is ever supposed to see.

But the FinCEN Files investigation was about so much more than leaked files.

Hubbard’s name doesn’t appear anywhere in the FinCEN documents. Yet he was one of dozens of people I spoke to – or tried to speak to – whose stories helped ICIJ connect one of the driest, most complicated set of documents ICIJ has ever tackled to one grieving family in Garland, North Carolina.

It started with a few words in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet that formed part of the thousands of records shared by BuzzFeed News. Four other people jailed in the same global fentanyl probe that sent Hubbard to prison were listed in a document, probably prepared by FinCEN, titled “VTB Bank Export.” VTB is a Russian state-owned bank. VTB denied wrongdoing and it’s unclear why this document was created.

The spreadsheet showed that, from 2012 to 2017 (the exact years that U.S. authorities alleged Hubbard and others imported fentanyl into the U.S.), the four people and others had moved more than $400,000 through MoneyGram, the world’s second largest money transmitter.

All we had to work with were the names of these four. Armed with that, I dived into court records where many of them had been charged. I read indictments, sentencing hearing transcripts, FBI affidavits and more. I learned when they were arrested and how fancy their homes were.

But, most importantly, the court records opened a window onto the victims of this drug trafficking ring and the money sent around the world that allowed it to happen.

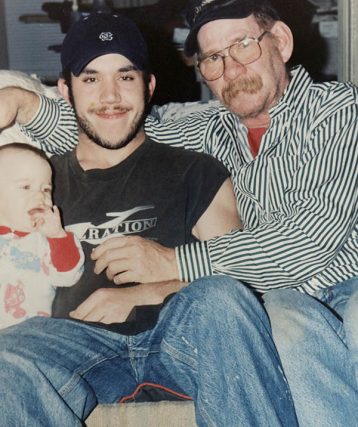

On page seven of one of the longer court documents, a plea agreement by one of the alleged drug ring participants, I read that U.S. prosecutors believed that the first person to die from this scheme was “J.W. in Garland, North Carolina, on or about January 19, 2014.” Others had died in North Dakota and Oregon. More still were injured.

Garland is a small place. It didn’t take me long, using the online obituary legacy.com, to identify Joseph Williams as the likely “J.W.”

But I had my doubts. In a court document, one of hundreds that I read, U.S. prosecutors also mentioned “James Williams”. Was I barking up the wrong tree? After a quick email and phone call, the U.S. attorney’s office in North Dakota told me that they had made a filing error. It was Joseph, not James, after all. (They wouldn’t answer any of my other questions, by the way).

Once I confirmed that Joseph Williams was the victim of a fentanyl trafficking ring whose key players were listed in our leaked documents, I tried to contact the family.

The Williams had moved since Joe’s death, so that didn’t help. I called the Garland post office, which confirmed that the Williams family still lived in town. I eventually contacted Joe’s sister, Emily Spell, through Facebook. Emily works mad hours as a nurse, so it wasn’t always easy to find time to speak, especially during the summer peak of COVID-19.

I eventually spoke to Emily on the phone. Emily told me everything she remembered about the day Joe died and what has happened since.

I promised to try to visit Emily, hoping that the COVID-19 lockdown would be lifted. I wanted to meet the family and I wanted to see Garland with my own eyes, a tiny town of fewer than 700 people, better known for its blueberries than for its connection to a vast money laundering ring.

I spoke to Garland’s mayor. Welcoming and friendly, she suggested that I postpone my visit. Garland was a COVID-19 hotspot, she said. The town is surrounded by hog farms, which have seen high infection rates among workers.

I waited. And waited. And waited. The FinCEN Files deadline was approaching.

After getting a COVID-19 test at my local fire station and assuring my editors that I would take all necessary precautions, I drove to Garland. I explored for a day, trying the local vinegar barbecue, strolling through the Piggly Wiggly supermarket, taking some photos in front of the shuttered Brooks Brothers store.

To be honest, it wasn’t where I thought my FinCEN Files reporting would take me. Before COVID-19, I had planned a trip to Turkmenistan and toyed with visiting a gold mine in Liberia to investigate other leads in the documents.

Instead, I met Emily, her mother and one of Joe’s kids at the family’s local Methodist church. We avoided sitting inside their home out of an abundance of caution due to the pandemic.

Emily and her mom laid out Joe’s photos before me, describing a boy and a man who was good at heart but, like all of us, had his fair share of problems. We talked about the music that had played at Joe’s funeral.

I had spent months at my desk in Washington D.C. reading through suspicious activity reports, Excel spreadsheets that didn’t always make sense, and putting into order what happened, when.

Now, in Garland, I was speaking to the people for whom the FinCEN Files were not an abstraction. The free flow of dirty money had contributed to their family member’s death. What if banks, MoneyGram or U.S. officials had acted earlier? Could Joe’s death have been prevented?

I asked Brandon Hubbard, in jail, if he knew the Williams family. He swears he doesn’t and that he had nothing to do with Joe’s death. But, there they were, one family in North Carolina and one felon in North Dakota, bound together by an ICIJ investigation that exposed the broken global anti-money laundering system. One used the system to his advantage, the others were victims of it.

It wasn’t easy for Joe’s family to share their story. But they were generous with their time and with their patience. “If it helps one person, I’m glad to have done it,” Joe Williams’ mother said.