The British Virgin Islands, a popular tax haven where secrecy rules have long attracted criminals, will introduce a public register of owners of companies created on the island.

The BVI, an overseas territory of the United Kingdom located east of Puerto Rico, has a well-documented history of being misused by drug traffickers, corrupt politicians, and tax evaders. Successive scandals, including exposés by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, have placed the BVI under pressure to increase transparency.

Andrew Fahie, BVI’s premier and minister of finance, told the island’s House of Assembly in September that his government would work “towards a publicly accessible register of beneficial ownership for companies,” albeit “subject to reservations.” Liz Sugg, the U.K. minister with responsibility for territories like the BVI, later tweeted that the public register would be adopted by 2023.

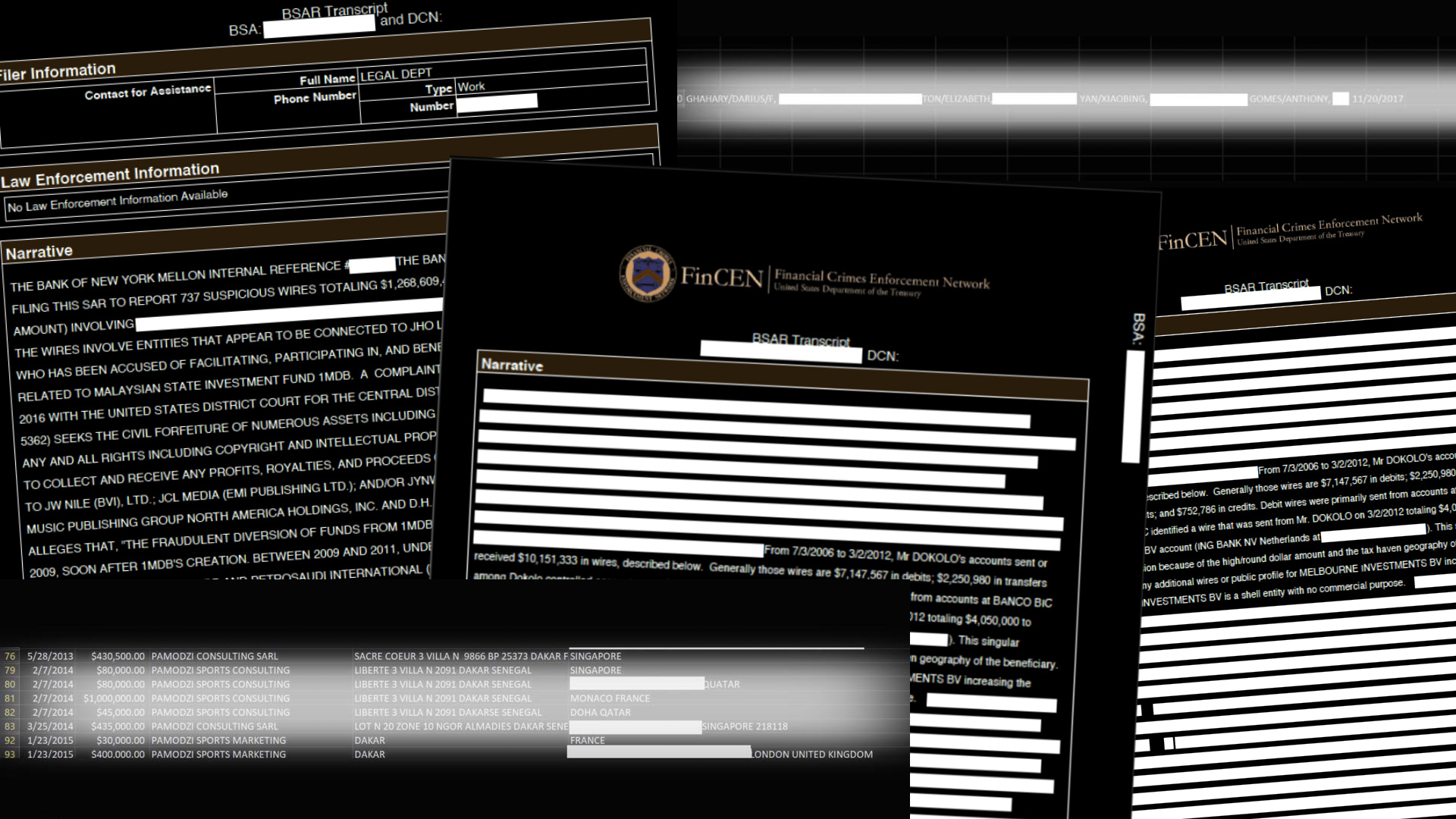

“Every time that there’s a global exposé on illicit finance, the BVI’s name comes up,” said Ava Lee, anti-corruption campaign leader from the nonprofit Global Witness. “The recent leak of files from FinCEN showed that at least 20% of the occasions when banks in the US raised suspicions of money laundering involved BVI companies, and half the companies exposed by the Panama Papers were registered there.”

There is currently no simple way for members of the public, journalists, or lawyers to identify a BVI company’s owner. Knowing a company’s owner can be key to determining whether laws have been broken and help trace money, homes or other assets in a divorce or other dispute. Countries and law enforcement can officially request information from the BVI. However, not all countries can make such requests and, even if they can, information can take significant time to arrive.

BVI, and secretive companies created there, have played an outsized role in major ICIJ investigations since 2014.

In 2014, reporters identified the oldest daughter of the late Philippine dictator, Ferdinand Macros, as a beneficiary of a BVI trust as part of the Offshore Leaks investigation. Officials later said that they would examine whether assets exposed by ICIJ were part of the estimated $5 billion her father amassed through corruption. ICIJ also revealed BVI companies owned by the sons of a former South Korean president embroiled in a tax evasion scandal and of China’s former ruler, Wen Jiabao.

The 2015 Swiss Leaks investigation revealed that HSBC Private Bank in Switzerland helped customers set up shell companies in BVI to skirt a new tax law. Many of those with secretive Swiss bank accounts protected their identity further by using the bank account under the name of a BVI company instead of in their own name, ICIJ revealed.

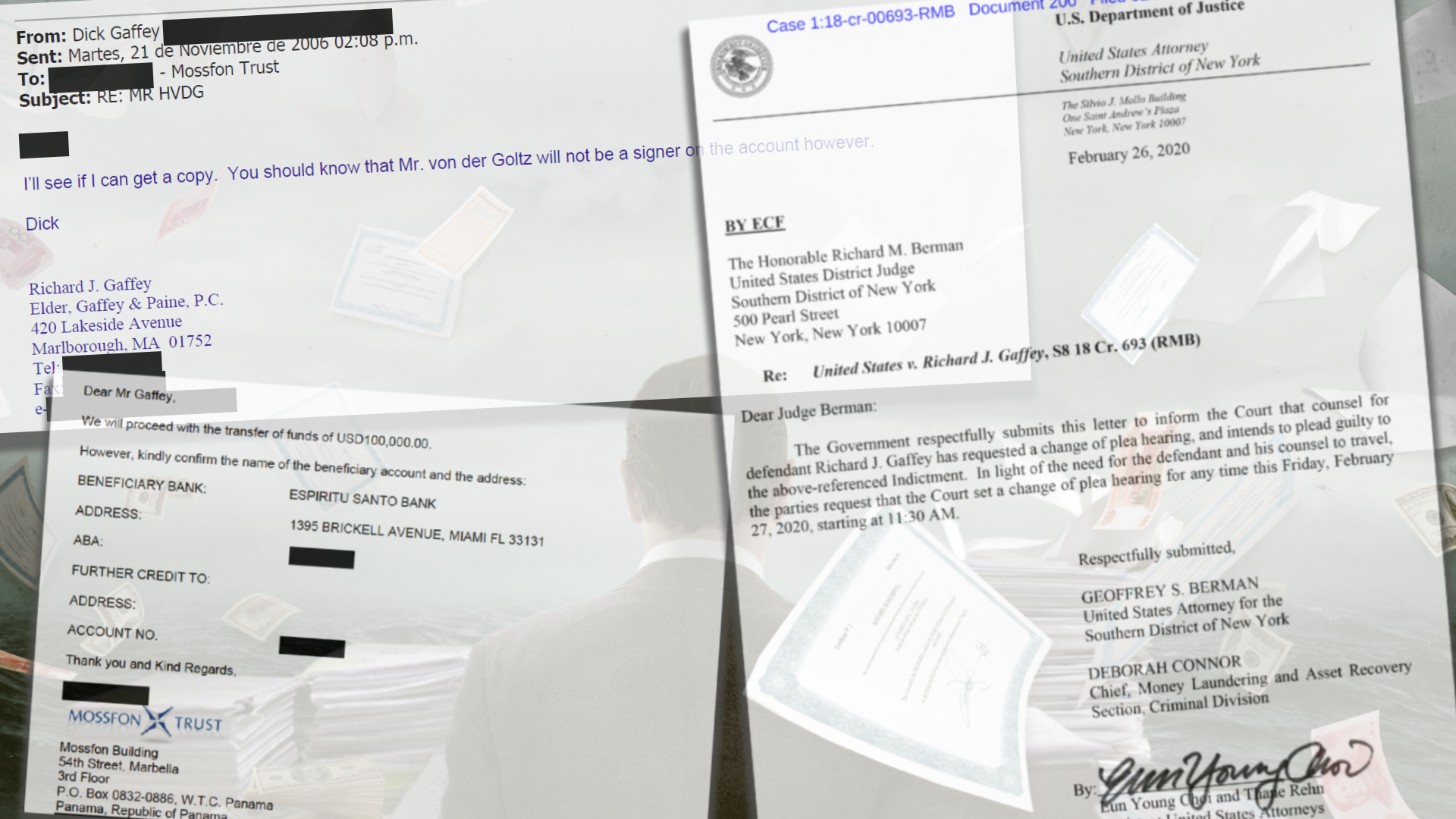

The BVI was the secrecy jurisdiction of choice for customers of the Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca, according to an ICIJ analysis of leaked files that formed the basis of the 2016 Panama Papers investigation. Mossack Fonseca created more than 113,000 BVI companies, outstripping Panama as the most popular tax haven.

In 2017, ICIJ also revealed flaws at top-tier law firm Appleby, which has an office in the BVI. Internal reviews found holes in the law firm’s paperwork and imperfect knowledge of high-risk customers, according to documents obtained by ICIJ as part of the Paradise Papers investigation.

ICIJ’s most recent investigation, the FinCEN Files, revealed that some of the world’s most profitable banks routinely process money for companies in tax havens whose owners are unknown. One in every five suspicious activity reports filed by banks and reviewed as part of the FinCEN Files investigation contained a client with an address in the BVI, according to an ICIJ analysis.

Other U.K. tax havens received mixed news this month.

Anguilla, a tiny island of 17,000 people, was placed on the European Union’s blacklist of countries and territories that fail to meet standards of transparency, fair taxation and commitments to global norms. Last month, ICIJ reported that Anguilla, whose officials once had a close relationship with scandal-tainted law firm Mossack Fonseca, had slipped further down a separate global transparency index.

In the same E.U. announcement, European ministers delisted the Cayman Islands, which has a zero corporate tax rate and has welcomed tens of billions of dollars in profits from the U.S., including from brand name companies like Coca-Cola and Pfizer. The territory is the “largest enabler of financial secrecy in the world,” according to the nonprofit Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index.

Experts and members of the European parliament expressed disbelief at the decision to give the Cayman Islands a clean bill of health and concern that the use of lists to punish smaller tax havens exempts countries like Switzerland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

“Blacklists, gray lists or white lists – lists of any kind – are divisive and counter-productive,” said Afton Titus, law professor at the University of Cape Town. “This process is less about ensuring global tax transparency and global tax fairness and more about creating a mechanism by which to publicly defend the interests of industrialized and developed countries like the EU countries,” Titus told ICIJ.

“How credible is a ‘tax haven blacklist’ that includes small countries such as Fiji, Samoa, Trinidad and Tobago and excludes or exempts some of the world’s biggest tax havens at the centre of recent major tax scandals highlighted by the Paradise Papers and Panama Papers?” said Liliane Mouan, a lecturer at Coventry University in the U.K.. “The blacklist process is yet another example of powerful nations wanting to play judge and jury while at the same time protecting the status quo.”