ACCOUNTABILITY

U.S. Treasury faces a wave of criticism over faltering push to unmask anonymous companies and track dirty money

Transparency activists warn that delays to U.S. reforms designed to thwart illicit money flows have grave global implications.

A landmark U.S. reform to stamp out anonymous companies that hide dirty money is in danger of effectively dying at the hands of the federal agency tasked with implementing it, advocates of the effort warn.

For months, the U.S. Treasury Department’s quest to build a database of company owners — which would lift the veil on millions of abuse-prone shell companies in the U.S. — has been beset by delays and multiplying disagreements.

The database itself stemmed from a rare moment in American policy life in which pretty much everyone agreed that there was a problem that needed to be solved. A group of lawmakers, industry representatives and advocates united to push through the Corporate Transparency Act, which was signed into law in early 2021. But that’s where the harmony ended.

In the years since, multiple flashpoints have flared, stemming from the often mundane process of officials drafting rules to implement the database. The same people who celebrated the passing of the legislation are now calling key aspects of the law’s implementation “misguided,” “fatal,” and “disastrous.”

The arguments center on core, complex questions over how the database will be operated, including who will be able to access the data, how rigorous the collection will be and whether the data will be verified.

“Not getting this right undermines anti-corruption efforts not just in the U.S. but has far-reaching impacts on the global fight against corruption,” Lakshmi Kumar, Policy Director of Global Financial Integrity, told ICIJ. Advocates for more transparency have consistently flagged the U.S. financial system as opaque and vulnerable to money laundering, and say the creation of a registry of company owners is crucial for combating illicit cash.

Not getting this right undermines anti-corruption efforts not just in the U.S. but has far-reaching impacts on the global fight against corruption. — Lakshmi Kumar, Global Financial Integrity

In September 2020, ICIJ, BuzzFeed News and more than 100 media partners published the FinCEN Files, exposing more than $2 trillion in suspicious transactions flowing through the global financial system via U.S.-based banks. Citing the public outcry that followed, U.S. lawmakers advanced a landmark anti-money-laundering bill named the Anti-Money Laundering Act, which included the Corporate Transparency Act. The law tasked the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network — FinCEN — with setting up the new database and writing the detailed regulations that would undergird the system.

Kumar attributes the bumpy rollout, in part, to FinCEN being badly underfunded and understaffed. The most recent point of contention arose after the Treasury published a draft version of the questionnaire in January that companies would use to report their ownership; the draft form would have allowed companies to say company ownership is “unknown” — apparently giving anonymous firms an easy way to opt out of the system.

“I can’t imagine what was going through the minds of the people drafting this form,” Gary Kalman, the director of Transparency International’s U.S. office, told ICIJ. “This is a roadmap for bad guys to avoid passing on their information.”

This concern prompted Democrats and Republicans in both the House and Senate to send a joint letter to the Treasury Department last week warning that the draft questionnaire’s box would “degrade” the law by providing criminals and other bad actors an “escape hatch.” The letter, dated April 3, not only criticized FinCEN form as undermining the database but also asserted that the agency’s move was contradicting the law it was tasked with implementing.

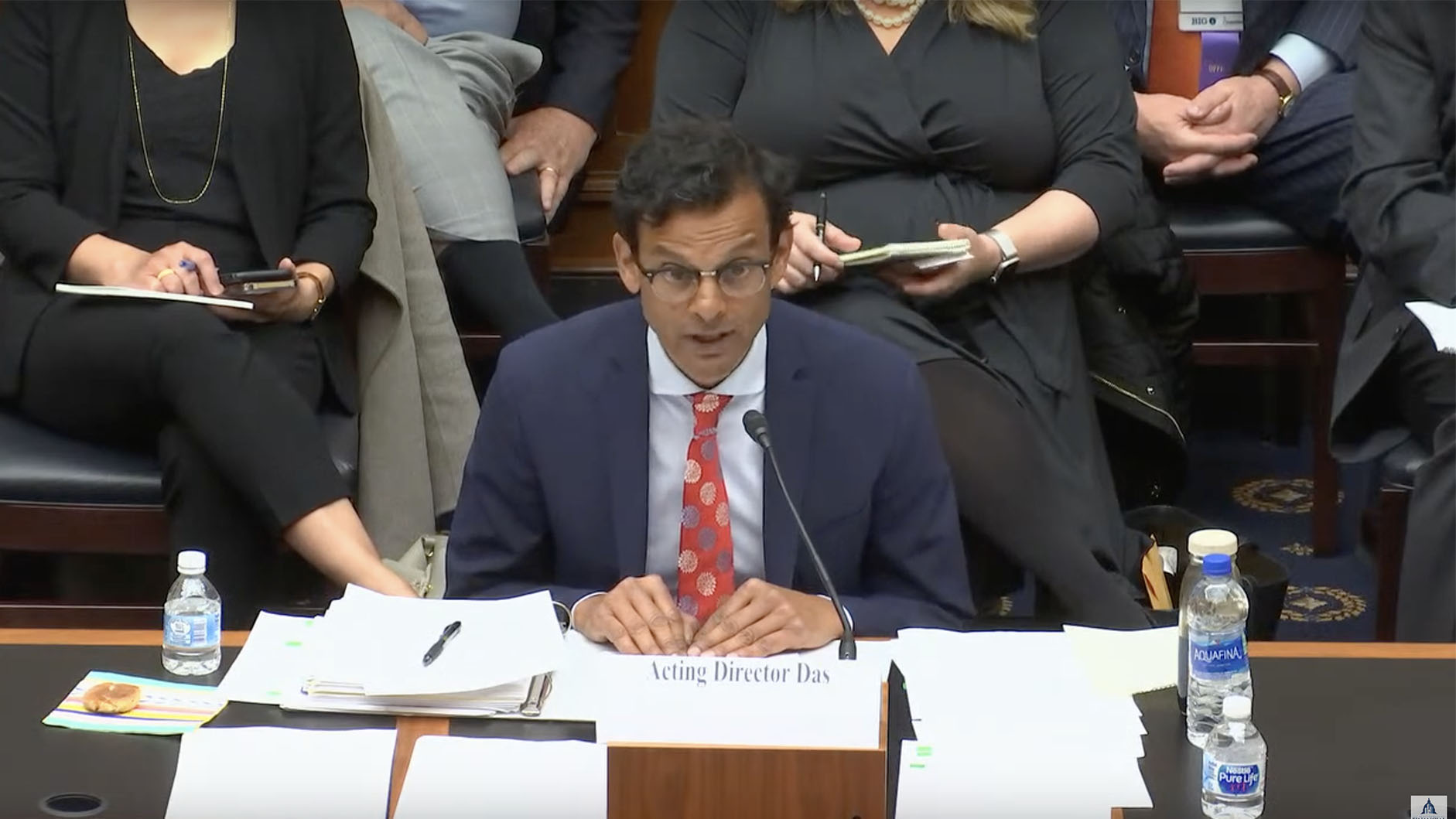

Late last month, FinCEN acting director Himamauli Das said that the draft questionnaire would be rewritten. A Treasury spokesperson wrote in an email to ICIJ that “the ‘unknown’ checkbox was not intended to provide any exception to the reporting obligation.” The Treasury official told ICIJ that the agency intends to make “clear that the reporting company is required to ensure that reports are correct and complete and all information is submitted.”

Advocates say they are cautiously optimistic that FinCEN’s revised form will remove the portion allowing companies to opt out of providing ownership data. But a more difficult challenge for advocates may lie in FinCEN’s proposed rules that limit who can access the database — rules that critics say could deal a devastating blow to the database’s workability.

The Corporate Transparency Act already excludes the general public from accessing the database, leaving the information restricted to law enforcement and financial firms. Although this limited access was a compromise that transparency-minded advocates grudgingly accepted, now even the banking and law enforcement agencies could struggle to access the data.

The access rules, released in December, state that local law enforcement officials would have to secure permission from a court each time they accessed a company’s beneficial ownership data. This would be a significant hindrance to investigators who often work on fast-moving cases and who, in many instances, would need to examine numerous company ownership records. Requiring “local law enforcement to obtain a court order goes against the legislative intent of the CTA,” said Kumar.

An added irony, advocates point out, is that other countries, including the United Kingdom, make this same type of company ownership data openly accessible to the general public via an easy-to-use online browser.

A slew of complaints, a sign of progress

FinCEN’s access rules would also restrict bankers’ ability to view the ownership data even more sharply. The rules would require compliance officials to ask for a bank client’s consent to seek their ownership information in the database. Once a client approves, the bank would also have to submit a request to be reviewed by Treasury Department officials each time they wanted to access ownership information.

In a letter submitted in February, the American Bankers Association, a major trade group of U.S. banks, said the Treasury’s latest proposed rule for the registry would so dramatically restrict bankers’ access to company ownership data and be “so limited that it will effectively be useless.”

ICIJ’s reporting has shown the difficulties bank-compliance officers grapple with in attempting to understand a profusion of secretive shell companies sending wires through their accounts. The FinCEN Files repeatedly showed compliance officers searching through their files on the shell companies in vain to determine who was behind firms or what their true purpose was. In one case, bankers couldn’t figure out whose money was behind a $100 million wire transfer between two shell companies and surmised incorrectly that it involved a British merchant that “deals in fruits and vegetables.” In reality, it was part of a vast offshore empire associated with Suleiman Kerimov, a Russian billionaire and politician close to Vladimir Putin.

The banking industry association’s comments, co-signed by 51 state-level banking associations, reveal a stark reversal for a group that had previously been a key supporter of the law mandating the database’s creation. Ross Delston, a Washington, D.C.-based attorney and anti-money laundering specialist, told ICIJ that requiring bankers to attain customers’ consent before accessing ownership data is one of the most egregious flaws of the Treasury’s proposed management of the database.

“This can only be thought of as an attempt to limit the utility of the registry and is not found in any of the registries around the world that are actually useful and publicly accessible,” Delston told ICIJ.

Advocates also worry that once the database’s users are able to access company data, the information may be incomplete or inaccurate. Advocacy group Transparency International cited the U.K. as an example, which, after years of neglecting to verify ownership information in its own public registry, has made an about-face. “The UK is now moving to verify reported information,” the organization said in a recent letter submitted to the Treasury Department, “and the U.S. must learn from their experience by doing the same.”

FinCEN has not yet proposed a rule that lays out a verification process for ownership information, but the Biden Administration signaled recently this is likely in the works. On March 29, the U.S. signed an anti-corruption commitment that included a pledge to “develop appropriate verification measures” regarding company ownership information.

Advocates say this is a sign that the Treasury will in fact pursue quality control on company ownership data.

“This is a huge step forward,” Erica Hanichak, government affairs director of the Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency (FACT) Coalition, told ICIJ of the commitment. “[It] showed promise.”