Emily Spell heard the screams from outside her parents’ red brick home.

She found her brother, Joseph Williams, 31, splayed on a mattress in the basement. His eyes, half open, were yellow. His lips were blue. His wife, Kristina, was pounding on his chest.

“Joe, wake up! Joe, wake up!” Kristina hollered.

Spell, a nursing student, started CPR. Each time she pressed down on his chest, white foam spluttered from Joe’s mouth and onto his favorite Batman pajamas.

Joe’s mother, who’d raced home from work at Piggly Wiggly, a regional grocery store in Garland, North Carolina, tore into the room. She lay down beside her only son.

“It’s OK, baby, you can go ahead and sleep,” Susan Williams said. “Do you want a cigarette? Are you cold?”

“I thought my mama had lost her mind,” Emily remembers. “Of course he was cold. Because he was dead.”

Joe’s family didn’t know what killed him. They had no idea that he was one of the first of tens of thousands of Americans who would be felled by fentanyl, the deadliest narcotic in the world. And even after they saw the autopsy report, it wasn’t until much later that they learned of the global forces responsible for Joe’s death.

It took a network of traffickers stretching back to China, relying on the easy movement of dirty money through brand-name financial institutions, to deliver lab-designed opioids to rural North Carolina and across the U.S.

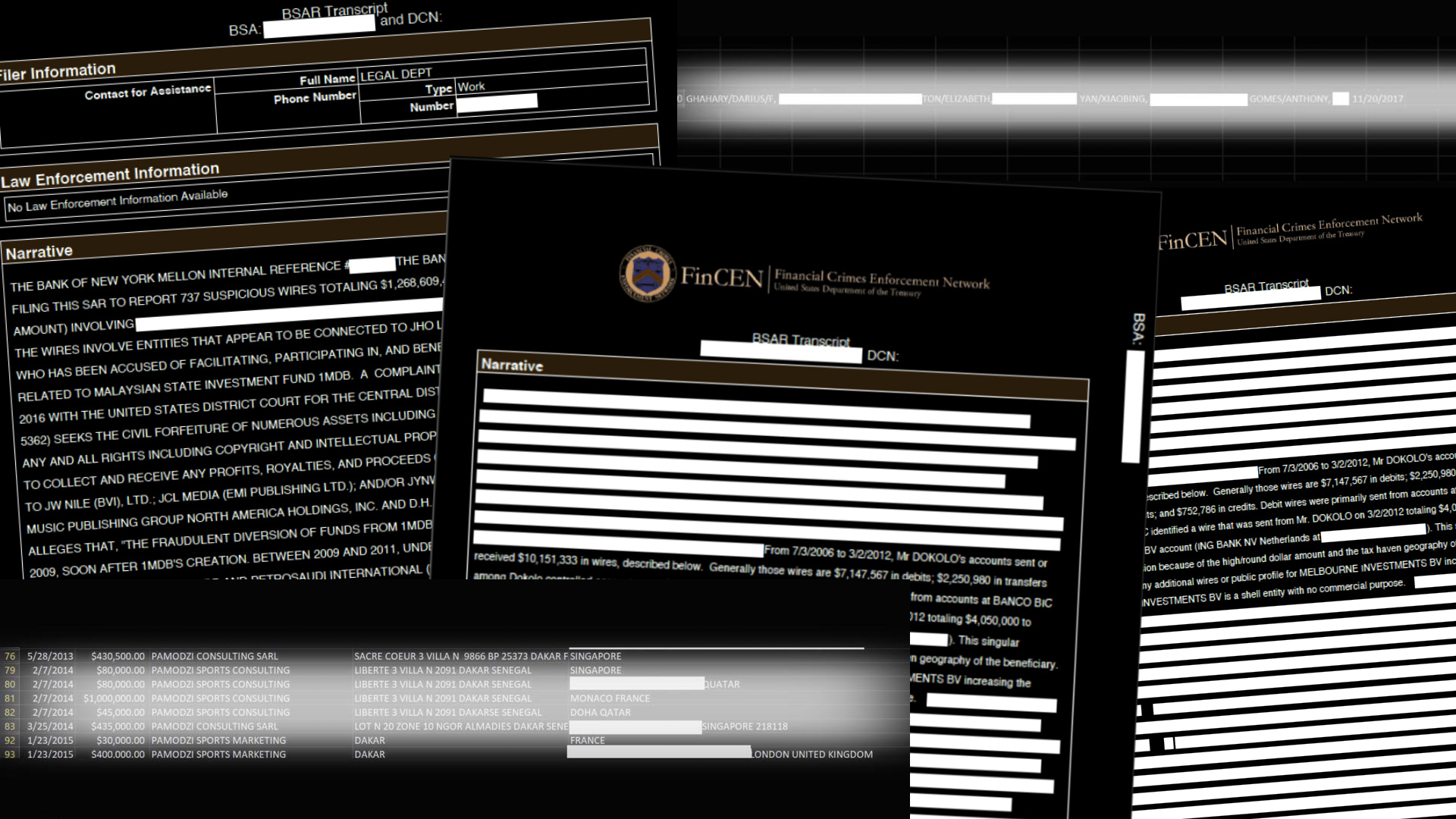

New details about how money that powered the fentanyl drug ring and more than $2 trillion in other suspect funds sloshed around the globe are contained in a cache of secret financial records obtained by BuzzFeed News and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

The files, known as suspicious activity reports, or SARs, provide a worldwide tour of crime, corruption and inequality, with starring roles played by politicians, oligarchs and honey-tongued swindlers, and crucial roles by the bankers who serve them all. The SARs show how the failure of banks and other financial institutions to thwart illicit money flows promotes criminality and suffering on a grand scale.

In a world beset by headline-grabbing crises, including a coronavirus pandemic that is destroying lives and economies, the unchecked piping of dirty money may not register as an immediate threat. But the consequence is profound: narcotraffickers and Ponzi schemers shift profits beyond the reach of authorities. Despots and corrupt captains of industry swell ill-gotten fortunes and consolidate power. Governments, starved of revenue, can’t afford medicine to treat the sick.

At the heart of these stories are real people hurt in real ways: families that have lost savings to predatory financial schemes, Olympic athletes cheated of victories by crooked officials, parents mourning sons and daughters fallen in battle, a mother crushed at work and a brother taken by drugs.

Joe Williams’ family and other victims often don’t know that their pain is, in part, the product of financial crime, or a violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 1956, “laundering of monetary instruments.”

“People may not be aware of issues like money laundering and offshore companies, but they feel the effects every day because these are what make large-scale crime pay — from opioids to arms trafficking to stealing COVID-19- related unemployment benefits,” said Jodi Vittori, a corruption expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

But criminal networks and the law enforcement officials trying to stop them understand that an untamed tide of dirty cash is the single most important requirement of a successful criminal enterprise.

Brandon Hubbard, in prison for life for importing fentanyl in the scheme that killed Joe, remembers that the police who arrested him seemed more interested in where the cash went than the powder known as China White. “That’s the first thing they asked me when they came in the door,” Hubbard said in an interview from prison. “‘Where’s the money?’” Hubbard denied that he knew or distributed drugs to Joe Williams.

The leaked documents, known as the FinCEN Files, include more than 2,100 suspicious activity reports written by banks and other financial players and submitted to the U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. According to BuzzFeed News, some of the records were gathered as part of U.S. congressional committee investigations into Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, while others were gathered following requests to FinCEN from law enforcement agencies.

The reports — dense, technical information bulletins — are the most detailed U.S. Treasury records ever leaked. They disclose payments processed by major banks, including HSBC, Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan Chase and Barclays. They describe journeys of dirty money that zigzag inexplicably around the world; from a kleptocrat’s spoils or a front company on the Atlantic coast, for example, via Wall Street bank to a sun-kissed tax haven in the Caribbean, a Singapore tower block or a financier in Damascus.

SARs are not evidence of wrongdoing. They reflect views by watchdogs within banks, known as compliance officers, reporting past transactions that bore hallmarks of financial crime, or that involved clients with high-risk profiles or past run-ins with the law.

FinCEN told BuzzFeed News and ICIJ that it does not comment on “the existence or non-existence of specific SARs.” It released a statement about unnamed “media outlets” that said “the unauthorized disclosure of SARs is a crime that can impact the national security of the United States.” Days before ICIJ and its partners released the FinCEN Files investigation, the agency announced it was seeking public comments on ways to improve the U.S. anti-money laundering system.

Four hundred journalists from almost 90 countries burrowed into the leaked records, often emerging with a thin thread of just one name or one address. They spent 16 months prying additional documents from sources, reading through voluminous court and archival records, interviewing crime fighters and crime victims and reviewing data on millions of transactions that took place between 1999 and 2017.

Sparked by the secret files, reporters traced a Rhode Island drug dealer’s dollars to a chemist’s lab in Wuhan, China; explored scandals that crippled economies in Africa and Eastern Europe and tracked tomb raiders who looted ancient Buddhist artifacts that were sold to New York galleries.

The dozens of political figures who feature in the documents include Paul Manafort, the former Donald Trump campaign manager who was convicted of fraud and tax evasion. JPMorgan reported that it moved money between Manafort and his associates’ shell companies as recently as September 2017, long after his ties to Russian-connected Ukrainian officials and suspected money laundering had been widely reported.

Often, the person tied to a suspect transaction was one step removed from the boldfaced name: a child, an associate, or, in the case of Atiku Abubakar — a former Nigerian vice president accused of diverting $125 million from an oil development fund — a wife. Years after corruption allegations against her husband surfaced, Rukaiyatu Abubakar moved more than $1 million of his money through Habib Bank to a company in the United Arab Emirates to buy an apartment in Dubai. (Atiku Abubakar has not been tried in court and denies wrongdoing).

Dozens of stories across the FinCEN Files investigation trace money transfers like these, from foreign capitals to companies that exist only on paper, handled by global banks that have long catered to oligarchs and despots and have felt little real pressure to stop. This system has had lasting consequences that ravage the lives of people like those you may know.

An Australian aromatherapist sent $50,000 to a cryptocurrency scam run out of the United States, Bulgaria and Thailand. A Texas retiree thought that he had found true love with an Austin college student he met online and paid into a Bank of America account owned by a failed Nigerian politician. Russian parents who needed to ferry their sick child to a hospital in St. Petersburg wired $15,000 to a used-car salesman in New Jersey who promised, but never delivered, a second-hand Honda.

And a North Carolina man nursing a secret addiction paid a few dollars for a white powder that traversed three countries and ended his life.

An overdose in Garland

“Emily, what the hell is fentanyl?”

Joe Williams’ mother was standing in her daughter’s kitchen holding the toxicology report that had arrived in the mail that day in 2014.

Emily Spell had heard of the opioid in nursing school. “Like, a pain medication they give to cancer patients,” she responded.

Williams, a father of four, lived on the eastern border of Garland, home to just over 600 people, blueberry fields and hog farms. “Greatness Grows in Garland” is a town slogan, but evidence of that greatness has been harder for some people of Joe’s generation to find. No new homes have been built in years, and local leaders recently disbanded the police force due to budget constraints. The town has been hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic.

On a recent summer day, locals, some wearing face masks, refilled propane canisters outside the bustling Piggly Wiggly and ordered cheesy sandwiches from Subway. The Curiosity Shop and other businesses in the center of town were closed. Weeds shot up out of cracks in the empty asphalt car park outside the shuttered Brooks Brothers shirt factory.

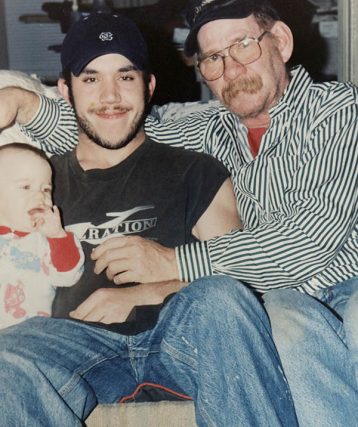

Emily knew that her brother used drugs; he was arrested in 10th grade for bringing marijuana to school and, more recently, had pawned his father’s work tools to buy cocaine. But the family didn’t realize how much and how often the healthy-looking, six-foot, 200 pound-plus Joe Williams used. Emily’s Joe was a guy who pulled funny faces in family photos; who, when they were kids, placed her in gentle choke holds as they watched professional wrestling and sneaked into her room at night to sleep because he was scared of the dark.

As an adult, Williams bounced between jobs, played plenty of “Call of Duty” and kept his drug addiction a secret. Days before his death, Williams received a package mailed from Canada with five painkillers and fentanyl powder.

In 2017, U.S. prosecutors named Williams — referred to only by his initials, “J.W.” — as the first American victim of a global plot to distribute deadly drugs. Next year, a federal judge in Fargo, North Dakota, will sentence Anthony Gomes who pleaded guilty to conspiring to launder money and to distribute drugs that killed Joe Williams and other Americans.

Authorities arrested Gomes near Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in 2017, not far from his $850,000, six-bedroom Tudor cottage, bought, prosecutors alleged, with drug money. Investigators seized $150,000, Gomes’ Maserati sports car and an all-terrain vehicle.

For years, Gomes and his girlfriend, Elizabeth Ton, sent bank transfers and money wires to China and Canada, where the group’s ringleader operated from his jail cell.

Prosecutors said Gomes, Ton and other members of the drug and money laundering “conspiracy” used offshore accounts, money transfers, a Bank of America account and encrypted communications to conceal their operations.

In an undated spreadsheet from the FinCEN Files, Gomes and eight others are linked to payments totaling more than $403,000 made between 2012 and 2017 via MoneyGram International, a Dallas-based money-transfer firm that in 2018 paid $125 million in penalties to U.S. authorities for violating a settlement with U.S. authorities intended to stop money laundering and fraud.

The FinCEN Files spreadsheet, a barebones list of more than 1,500 suspicious activity reports, was titled “VTB Bank Export,” referring to a state-owned Russian institution known as Russian President Vladimir Putin’s “piggy bank.” The U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned VTB Bank in 2014 in response to Russia’s annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula. It is unclear what connection VTB Bank had to the MoneyGram transfers or why the document was created.

VTB Bank said that it “operates strictly according to local and international laws and complies fully with all local and global regulatory standards.” The bank has “not received any complaints about our activities from USA authorities” and is “unable to comment on this matter as we have not been given access to the relevant documentation that the query refers to.”

Three of the eight people named with Gomes in the spreadsheet have been charged with or convicted of drug trafficking. One, Xiaobing Yan, is the first manufacturer of fentanyl to be indicted in U.S. history. Yan, 43, operated out of Wuhan, China, and is still wanted by U.S. authorities. He denies breaking Chinese laws or knowingly selling substances banned in the U.S.

The other two were Ton, Gomes’ girlfriend, and Darius Ghahary. Both were charged with fentanyl-related crimes in 2017. MoneyGram reported suspicious transfers tied to Ghahary more than a decade after New Jersey authorities fined him in a high-profile internet fraud case.

It is unclear exactly who paid whom and the exact route the fentanyl took to reach Garland. U.S. prosecutors trying Gomes’ case declined to answer ICIJ’s questions, citing ongoing litigation.

A day laborer in Turkmenistan

The flour, when it arrived at the store, smelled foul. The oil was black and bitter.

It was 2016, and Turkmenistan’s economy was spiraling downward. The poor foraged from dumpsters. Within two years, inflation would be second only to Venezuela’s.

By day, laborers lugged sacks of cement by bicycle for a few manat, the Central Asian country’s currency, which seemed to shrink in value overnight. In the evenings, husbands and fathers crowded outside black plastic doors of government-owned supermarkets, where shelves were empty except for overpriced imports.

“There was never enough to eat,” one Turkmen, a day laborer from the southern oasis town of Mary, told ICIJ. He asked not to be named for fear of putting his family at risk. “People waited for flour until midnight, and the shop owners could not say when it would come.”

This year, the nonprofit Freedom House ranked Turkmenistan more repressive than North Korea and one of the four “Worst of the Worst” countries in the world for political and civil rights. Experts say that nothing happens without the approval of the president, Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov.

In Ashgabat, the capital, citizens cannot withdraw more than $23 a day from the bank. They cannot open a window along an avenue along which Berdymukhamedov may pass. This year, the president reportedly banned the word “coronavirus.”

The capital’s name, Ashgabat, means “City of Love.” Because of the hunger, police-state repression and corruption, many know it by another name: City of the Dead.

Corruption in Ashgabat, as in many of the world’s capital cities, is sustained by the surreptitious movement of money through offshore outposts — and, often, through some of the world’s richest banks.

Nearly three dozen suspicious activity reports reviewed by ICIJ describe payments linked to Turkmenistan and totaling $1.4 billion between 2001 and 2016. “Suspicious” does not necessarily mean illicit, but bank compliance officers watching the transfers determined that they deserved more scrutiny.

“The wires appear suspicious because they were often sent in a repetitive nature and typically involved suspected shell-like entities,” an employee in Bank of New York Mellon’s legal department wrote off nearly $100 million in transfers during the last three months of 2016.

Some U.K.-based companies received money from Turkmenistan even though they had reported to regulators that they weren’t actively engaged in any business, according to an ICIJ analysis.

In one case, Turkmenistan’s trade ministry sent $1.6 million to a company in Scotland called Intergold LP, according to leaked records. The bank’s records indicated that the payment was for “confectionery” — or sweets. The payment left the ministry’s bank account in Ashgabat, passed through Deutsche Bank in New York and arrived in a Latvian bank account held by Intergold.

Intergold LP was created 10 months before its transactions with the Turkmenistan government, records show. Its listed address is a store called Mail Boxes Etc. in Glasgow, Scotland. “MAKE THIS YOUR BUSINESS ADDRESS,” the storefront suggests.

Intergold has since been renamed SL024852 LP. It’s not clear who owns the business or whether it has any legitimate purpose.

James Dickins, who signed official registration documents at the time of Intergold’s creation, also signed off on accounts for at least 200 other companies in England, according to an ICIJ analysis of companies in the FinCEN Files. British companies have emerged in recent years as popular tools to hide crooks’ and corrupt officials’ bounties.

ICIJ was unable to reach Dickins. Daniel O’Donoghue, who also signed Intergold’s registration application, told ICIJ that his corporate work is supervised by U.K. anti-money laundering regulators and meets the required high standards of due diligence. “Re: Intergold LP if you have evidence of a crime you should pass it to law enforcement,” O’Donoghue said.

“This definitely sounds like a case where a shell company has been used to stash funds from state coffers,” said Annette Bohr, a research analyst at London’s Chatham House think tank who specializes in Central Asian kleptocracies. “They were likely thinking that putting down ‘confectionery’ will not ring any bells.”

Turkmenistan’s trade ministry did not respond to questions sent via its embassy in U.S.. The ministry’s online contact form did not work.

In documents seen by ICIJ, Deutsche Bank did not explain why it found the transactions suspicious. The bank declined to discuss its relationship with Turkmenistan. It told ICIJ that, in general, “discussing potential SARs … would be a criminal violation of US (and other) law.” Banks file SARs regularly and “thus help the authorities to catch and prosecute those engaged in criminal activity,” the bank said. “Deutsche Bank is actively monitoring for suspicious conduct and shares relevant findings with the authorities.”

Deutsche Bank’s role in the transactions was as a correspondent bank — meaning that it enabled the Turkmen banks used by ministries and well-connected entrepreneurs to convert manats into dollars and pay into other accounts around the world.

It’s a familiar role: the German institution was the international vault of choice for Turkmenistan during the murderous regime of former president-for-life Saparmurat Niyazov.

Deutsche Bank held up to one-third of the country’s revenue in accounts accessible only by Niyazov, according to Global Witness, an anti-corruption group. One former chairman of the country’s central bank told the group that the billions of dollars at Deutsche Bank were effectively Niyazov’s “personal pocket money.”

A Senegalese in Paris, a Tunisian steeplechaser

On a mild June day this year, Lamine Diack, an octogenarian from Senegal who was once the most powerful man in international athletics, appeared in a courtroom in northwest Paris to face corruption charges.

“I am starting to become an old nail,” Diack told the courtroom as he struggled to remember details of the graft during his watch as president of the International Association of Athletics Federations.

Diack, in glasses and a blue and white dotted tie, faced prosecutors miles from Hotel California on the Champs-Elysées.

It was at the four-star art deco marvel that Diack’s son and alleged partner in crime, Papa Massata Diack, made a final splurge before their arrest in 2015, according to bank records sent to FinCEN.

The younger Diack’s $30,000 hotel booking was among 112 payments flagged as suspicious in 2016 by Citibank, according to records. For years, the bank had witnessed payments — to London, Singapore, Doha, Moscow, Beijing and elsewhere — that experts say should have alerted diligent bankers much earlier.

“If money is going to consulting firms with no employees, luxury stores, that raises red flags,” sports governance expert Roger Pielke told ICIJ. “It’s not necessarily the money going around the world that’s the problem, it’s the combination of the money and the destination.”

As IAAF president, the elder Diack joined a vast bribery apparatus that enabled what prosecutors allege to be one of the most audacious doping schemes in sports history.

Lamine Diack and his son solicited $3.8 million in bribes, mainly from Russia’s sports ministry, to hide the results of drug tests showing that Russian athletes had taken performance-enhancing substances, French prosecutors allege.

After the scandal broke, the World Anti-Doping Agency found that the elder Diack “sanctioned and appeared to have had personal knowledge of the fraud and the extortion of athletes.” It also stripped several Russians of medals won in the 2012 Olympic games.

Diack also skimmed $1.5 million from Russian sponsorship and television deals to finance an election campaign in Senegal, according to prosecutors. French authorities are investigating whether bribes were paid to influence the selection of host cities for the Olympics and world championships.

Diack did not reply to ICIJ’s questions. Days before publication of the FinCEN Files, the Paris court sentenced Diack to four years in prison for corruption and breach of trust. His lawyers called the decision “unfair” and “bewildering.” Papa Massata Diack was sentenced to five years in prison for complicity in acts of corruption and fined more than $1 million. On Twitter, Papa Massata Diack said he was innocent and “surprised by the verdict,” which he said was based on “inadequacies” by prosecutors. Both men were cleared of money laundering. They will appeal.

Diack’s trial unfolded in Paris; the alleged financial chicanery that put him in the dock was global.

Over 72 hours in February 2013, for example, a Senegalese company, Pamodzi Consulting, scattered $1.25 million to a network of unusual clients: a Paris-based jeweler, Lamine Diack, a Russian sports federation and a retailer selling luxury watches, perfume and beauty products.

“The involvement of this French company in a sports marketing consultancy contract seems to be inconsistent with its declared sector of activity — namely the ‘retail perfume and beauty products trade,’” France’s financial intelligence agency, Tracfin, wrote to prosecutors about the Paris boutique, according to documents seen by ICIJ.

It was a lot of cash for a business in downtown Dakar with no obvious website.

It took two years for Citibank to realize that it had approved transactions that were part of a major sports bribery scandal.

Accounts at Standard Chartered, Deutsche Bank, Barclays, JPMorgan Chase and UBS also sent or received suspicious payments reported to French investigators, according to confidential documents reviewed by ICIJ.

Nearly a year after Diack’s arrest in 2015, Citibank reported 112 wire transfers worth $55.7 million dating back to 2007. One of the most recent suspicious payments – the $30,000 reservation down payment to Hotel California in Paris — was sent a few months before Diack’s arrest. A $45,000 wire transfer went to a car dealer in Qatar and another, for $435,000, to a Singapore company, Black Tidings, based in a public housing complex.

The money reported to FinCEN was only part of a torrent of dollars, francs, rubles, renminbi and euros that allegedly went into the pockets of coaches, doctors, administrators and government ministers in one of sports’ grubbiest scandals.

Along the way, athletes were cheated out of lifelong dreams.

Russian Yuliya Zaripova accepted a gold medal for the 3,000 meter steeplechase at the 2012 London Olympics before a cheering crowd and a global television audience of millions.

Tunisian runner Habiba Ghribi finished second.

Zaripova was stripped of her victory in 2016 after a retest of a urine sample showed that a drug test’s positive result had been concealed as part of the Russian doping scheme. Ghribi was later awarded the gold during a small, ad hoc Sunday night ceremony near Tunis on the margins of an athletics tournament for young adults.

Losing to a drug cheat cost Ghribi tens of thousands of dollars in winnings and sponsorship deals, she told ICIJ reporting partner Inkyfada.

“A champion and a runner-up — it isn’t the same thing,” she said.

Cave-in in Ukraine, head-scratching on Wall Street

“We sat expecting a miracle,” Olha Prykhodko said, remembering the day nine years ago she prayed in church to see her mother one last time. “And every time they would bring out a new human being in a black plastic bag, that hope would vanish.”

Prykhodko described how her mother, Nadezhda Kulinich, looked at the funeral. Kulinich’s dislocated jaw was wrapped in white bandages. Her fingers were smashed and her arms were blue — signs of a futile attempt to protect her face as tons of rock, metal and concrete rained down on her.

On July 29, 2011, Kulinich was one of 11 killed at a state-owned coal mine in eastern Ukraine when a tower collapsed onto the building where employees sorted coal from rock.

“Mom kept complaining that everything was falling apart,” Prykhodko told ICIJ partner Kyiv Post. Kulinich even told a visiting safety commission before the accident that “bricks kept falling on their heads,” Prykhodko said.

Employees grumbled that the collapsed tower hadn’t been replaced in 50 years.

Prykhodko, now with a daughter of her own, blames the “whole chain of guilt going all the way up to the government in Kyiv.” From her house window, she can see the spot where her mother died.

Ukrainian miners say rampant corruption puts them at risk.

Many of the country’s coal mines, including Bazhanov, where Kulinich died, are state-owned. They have long been the favorite source of plunder for kleptocrats, according to anti-corruption campaigners, employees and officials.

Across the industry, equipment failures are a constant concern. Mines have reported having barely more than half the masks needed to keep miners breathing in the event of a collapse. The miners’ union complained in an interview with a Ukrainian magazine that old equipment is taken from idle mines countrywide and simply repainted before being reassigned.

The Bazhanov tower collapse, in the city of Makiivka, was one of three mine accidents in Ukraine that week that together killed at least 39 men and women. All occurred in the country’s coal-rich east, near the Russian border, where today two rogue “people’s republics” operate with Kremlin backing.

An official commission identified aging equipment as a possible factor in the Bazhanov tower collapse and recommended changing how and when towers are inspected.

Supplying the Bazhanov mine was an obscure Cyprus company called Tornatore Holdings Ltd. Months after Kulinich’s funeral and 5,000 miles away, Peggy McGarvey, Deutsche Bank’s top Wall Street compliance officer, tried to figure out who owned Tornatore.

What caught McGarvey’s attention wasn’t the deadly accident but warning signs the bank noticed after processing two large payments on Tornatore’s behalf.

In December 2011, Tornatore received $5.5 million from a Ukrainian mine equipment subsidiary called LLC Gazenergolizing. The next day, Tornatore sent $999,994 to a large Russian leasing company, partially owned by the Kremlin.

The high-value payments, some rounded almost to the nearest thousand or million in what experts consider a “fingerprint” of fraud, capped off a year of Deutsche Bank concerns about Tornatore. The company had made suspicious payments and had no obvious home or “line of business,” bankers wrote in reports beginning in March 2011, a few months before the accident at the Bazhanov mine that summer.

McGarvey’s team saw that the leasing company described the latest wire transfers as presents and a loan repayment, but the bankers wanted more information, according to the bank’s report from February 2012. The leasing company’s Russian bank, Globex, had assured Deutsche Bank, in response to earlier concerns, that “the client didn’t make suspicious operations.” But McGarvey’s colleagues had persisted, asking Globex: “Please provide the business information for Tornatore.”

“No information,” the Russian bank replied. Months later, McGarvey, too, was none the wiser.

McGarvey, who remains Deutsche Bank’s head of suspicious activity reporting in the United States, did not respond to questions for this story.

It took Ukrainian journalists to connect Tornatore to the Makiivka accident.

In 2011, Tetiana Chernovol and Yuriy Nikolov reported that Tornatore was linked to Yuriy Ivanyushchenko, a politician close to then-President Viktor Yanukovych. It was the vehicle for controlling Gazenergolizing, which had a monopoly to supply the country’s mines with equipment.

Nikolov and Chernovol, who was a member of Ukraine’s parliament from 2014 to 2019, wrote that the state-owned mine had bought replacement gear from Gazenergolizing before the collapse, but they couldn’t determine if gear had been delivered or even if the order was legitimate.

But Ukraine’s state auditing agency published a report in 2011 that painted a bleak picture of the mine’s operations. It found $21 million worth of damaged equipment at the Bazhanov mine’s headquarters, miles from the accident, and identified $205 million in “shortcomings in accounting, gross violations of financial and budgetary discipline.”

Ivanyushchenko fled after Ukraine’s 2014 revolution and is under investigation by authorities in Ukraine and Switzerland for allegedly embezzling millions of dollars earmarked for energy projects. Through Swiss lawyer Vincent Solari, Ivanyushchenko denied owning or holding shares in Tornatore or Gazenergolizing. “The alleged ‘informations’ on which you seem to refer are wrong,” Solari said.

‘Anyone can be a trafficker’

Brandon Hubbard, the drug trafficker now in a North Dakota prison, didn’t see himself as a financial crook.

“I think of money launderers as people who invest in car washes or restaurants” to make dirty money legitimate, Hubbard told ICIJ, or who do “what Russian oligarchs do in getting their money out of Russia into American real estate.”

Then he became one himself. Hubbard, a former high school wrestler who grew up in Portland, Oregon, said he was shocked when the police told him that he was charged not only with distributing deadly drugs but with financial crime, too.

“I never considered anything I did as money laundering,” Hubbard said. “But, you know, I was sentenced to eight years for it.“

More than 31,000 Americans died from synthetic opioids, including fentanyl, in 2018. Fentanyl and other laboratory-made drugs, some 10,000 times more potent than morphine, now kill more Americans than any other opioid. The U.S. Treasury Department says that financial crime makes it all possible.

The department last year issued an advisory to financial institutions to raise their awareness of schemes that enable the flood of opioids. Financial and court data show that fentanyl traffickers range from hardened criminals with networks of intermediaries to a Pittsburgh resident who paid via MoneyGram to have 100 grams of fentanyl delivered to an address under the name Avon Barksdale, a fictional character from the HBO series “The Wire.”

“Anyone can be a trafficker now because of smartphones,” said Donald Im, an assistant special agent in charge with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.“If anyone can be an Uber driver, anyone can be a drug trafficker.”

Traffickers use “all methods of the economy and the financial system,” said Im, who worked on Operation Denial, an ongoing investigation into the trafficking of fentanyl and other drugs. Hubbard’s and Anthony Gomes’ convictions were the results of the operation.

A few months ago, police called Emily Spell’s home with an update. They’re having trouble nabbing the “main drug lord” from China, Emily remembers from the call.

“As small as this town is and as rural as this town is,” she said, “for my brother to have gotten drugs that ended up coming from all over the world, it’s really mind-blowing.”

Contributors: Agustin Armendariz, Simon Bowers, Wahyu Dhyatmika, Emilia Diaz-Struck, Momar Dieng, Abdelhak El-Idrissi, Azeen Ghorayshi, Adebayo Hassan, Karrie Kehoe, Mohammed Komani, Tanya Kozyreva, Malek Khadhraoui, Vlad Lavrov, Andrew W. Lehren, Anna Myroniuk, Toshi Okuyama, Delphine Reuter, Mago Torres, Tom Warren, Amy Wilson-Chapman, Farruh Yusupov