Sydney — Not long after Oleg Deripaska was named Russia’s richest man for 2008, his company’s Australian chairman wrote to the Department of Climate Change in Canberra with a dire warning: The oligarch’s considerable investment in Australia was being threatened by the plan to tackle global warming being advanced by the government of Prime Minister Kevin Rudd.

Deripaska had built his fortune, estimated then at over U.S.$28 billion, by becoming the major shareholder in RUSAL, an aluminum empire that reaches across the globe from Siberia to Australia. Along with mining and minerals giant Rio Tinto, the world’s largest aluminum producer, Deripaska owns the Queensland alumina refinery in Gladstone, a plant that employs 1,050 workers and each year churns out around four million metric ton of alumina, which in turn is made into aluminum (or as it known in Australia, aluminium). Like aluminum, alumina is made by using vast quantities of electricity. And in Gladstone, electricity comes cheaply — from burning black coal that spews greenhouse gas into the atmosphere.

In his climb to the top, Deripaska has survived a stand-off with the Russian mafia, developed a close friendship with Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, and fought the U.S. State Department when it revoked his visa. Characteristically, he also managed to hire one of the canniest lobbyists in Australia as RUSAL’s local chairman when he bought into the Queensland refinery. The chairman, John Hannagan, had worked a decade ago with the Australian Aluminium Council to shield the industry from climate change laws. He was now putting his extensive industry experience to work for Deripaska’s refinery, warning the government that its plans to cut Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions would be “destructive for jobs, destructive for existing and new investment, and destructive in terms of global energy efficiency”.

Hannagan is just one of the scores of influential lobbyists, business executives, and union leaders who have fought over the last year to weaken or “brown down” Australia’s first comprehensive plan to cut its greenhouse gas emissions. The carbon pollution-reduction scheme, which failed to pass the Senate in August, is now under consideration again, and the lobbying has resumed in earnest. The centerpiece of the plan is an emissions trading program that would for the first time put a price on carbon emissions in Australia.

A Host of Lobbyists

The stakes for Australia could not be higher. As the hottest and driest inhabited continent on earth, the country is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Without a global effort to reign in greenhouse gases, warns the country’s leading scientific body, declining rainfall and resulting drought could slash food production by almost half in the nation’s main agricultural region. Australia is currently amid a years-long drought that is believed to be the worst in a century. Its reach has extended from the agricultural heartland to cosmopolitan Sydney, where the air was reddened in September when high winds swept dust from the continent’s parched interior to the coast. If worldwide greenhouse gases are not reduced, people who live along the coasts also would experience increasingly severe storms and flooding compounded by a rise in sea levels. And in rural areas, more ferocious and frequent bushfires would likely take a heavy toll in property damage and human lives.

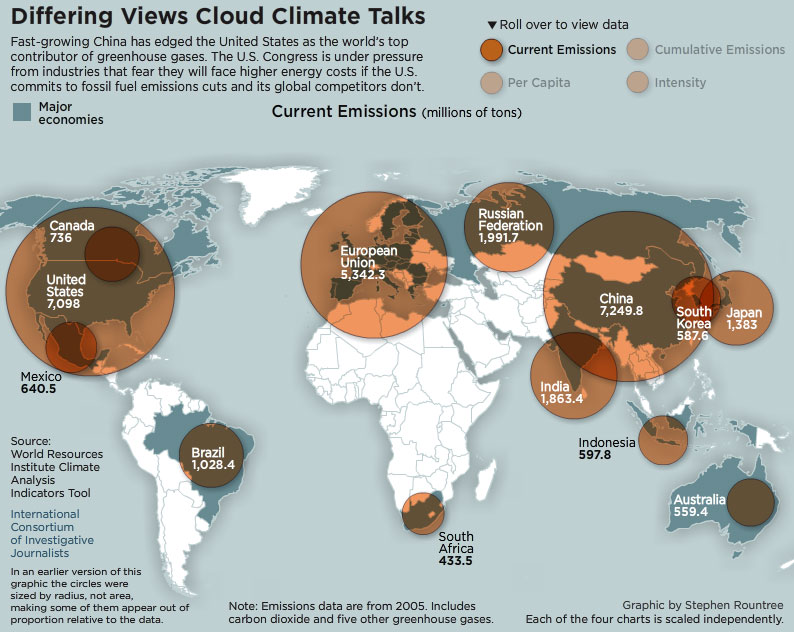

Despite this catastrophic outlook, many Australians, especially those in business, are not gripped by an urgency to change their ways. Australia’s heavy reliance on cheap coal-fired electricity for its homes and businesses makes it per capita the highest greenhouse gas emitter in the developed world. But cheap power also underpins the country’s enviable national wealth. As Australia grapples over who should bear the cost of cutting greenhouse emissions, some of the biggest polluters are making the case that the burden shouldn’t fall too heavily on them. And as players on the global business stage, they are making the same case internationally..

The top 20 companies that are expected to receive assistance from the Australian government to reduce emissions employ 28 lobbying firms, according to a Sydney Morning Herald analysis of the government’s lists of registered lobbyists. Nearly half the lobbyists working for these firms are former politicians, senior government bureaucrats, or political advisors. They include John Dawkins, a former federal treasurer is now a director of lobbying firm Government Relations Australia that represents BP, Peabody Resources, and The National Generators Forum, a power industry trade group. Rio Tinto’s executives have also joined the fight against the Rudd government plans, along with senior figures from the world’s wealthiest coal, gas, aluminum, and power companies — all aided by armies of lobbyists.

The cumulative result of the business campaign has been to soften the impact of the emissions trading scheme on their bottom line. Government assistance to help 20 major greenhouse gas emitting companies affected by the scheme is estimated at over AU$11.7 billion. A study by corporate consultants RiskMetrics, commissioned by the Australian Conservation Foundation, estimates that over the first five years of the scheme, Rio Tinto would get AU$2.7 billion in assistance, while U.S. aluminum giant Alcoa would get AU$1.7 billion. Among the other top 20 recipients of assistance are oil and gas companies Shell, Chevron, Woodside, BHP Billiton, and Caltex. The companies’ arguments made much of the 13,800 people who work in the industry, but this does not convince everyone. “I think the aluminium sector has done particularly well,” says Paul Toni, a climate campaigner for environmental group WWF. “I think it was excessive.”

It is this kind of concession-making, as the emissions trading bill moves forward, that has put even the government’s supporters in the environmental movement on the verge of walking away. Bearing the brunt of much of the industry lobbying is Australia’s Climate Change minister, Penny Wong. A skilled lawyer who worked with the forestry and construction union before she became a Labor Party minister, Wong argued forcefully with many corporate chief executives during the initial negotiations over the climate bill. The crux of her argument was that the scheme had to be credible and financially responsible. The more concessions went to one industry, she argued, the less compensation there would be for households and other businesses.

But when the global financial crisis hit last year, bringing job losses and threats of even more unemployment, pressure from the country’s labor unions intensified. Paul Howes, the head of the country’s largest blue collar union, the Australian Workers’ Union, was a crucial player. Representing workers in the aluminum, steel, and gas industries, Howes echoed industry arguments that the government’s original emissions-reduction plan would cost local jobs without saving the planet. “The global financial crisis was my greatest ally,” Howes told colleagues.

Industry has another big ally in Australia’s opposition Liberal Party, which includes many global warming skeptics. The government can’t get climate change legislation through the Senate without support from the opposition, whose leader, Malcolm Turnbull, is under intense pressure from members of his own party to demand more concessions for business. He continues to do so, while also promising to cut greenhouse emissions.

Battle over Emissions Trading

The idea of the emissions trading scheme is that companies must pay to pollute, buying one permit for each metric ton of carbon dioxide they release into the atmosphere. Permits are expected to cost around AU$25 a metric ton after July 2012. The cost is supposed to be passed on to the consumer, pushing both businesses and consumers toward making and buying goods that are less polluting.

Companies like Rio Tinto and Alcoa have argued strenuously that their competitors overseas don’t yet have to pay for their emissions, putting them at a disadvantage. So the government has offered businesses like aluminum smelters almost 95 percent of their permits free for the first five years of the scheme to allow them to adjust to the new requirements and to save jobs.

The free permits would slash the costs to business of cutting greenhouse gases. Martin Parkinson, the senior bureaucrat in the federal Department of Climate Change, estimates that companies like aluminum producers would face a carbon cost of just AU$2 per metric ton in 2012. To put this in perspective, the price of aluminum peaked on the London Metals Exchange at U.S.$3,300 per metric ton before the global financial crisis, and it is still trading around U.S.$1,900 per metric ton.

Minister Wong has tried to hold the support of environmental groups by promising that the government will periodically review the free permits and gradually reduce the amount. The government has also made a qualified offer to put a tough limit on Australia’s greenhouse emissions for 2020. If a strong agreement to cut greenhouse gases emerges from the United Nations climate talks in Copenhagen next month, the government has promised to cut emissions by 25 percent from levels in the year 2000. Without such an agreement, Australia’s target is a cut of as low as five percent..

But the government’s critics say most of the expected cuts in greenhouse emissions will not be made by companies in Australia. The Rudd government’s emissions trading scheme allows private businesses and the federal government to buy an unlimited number of carbon permits on the world market, so it is likely that Australian companies would be making lower-cost investments in greenhouse gas-cutting projects in countries like India and Indonesia rather than taking the more costly route of reducing their own emissions.

Indeed, figures buried in the Treasury Department’s modeling of the emissions trading scheme show that the 2020 target would only be achieved through large purchases of international carbon credits by business or the government. Companies or countries earn these permits, verified by the U.N., when they fund a project to cut greenhouse gases in poorer nations.

Wong rejects the claim that most of Australia’s cuts will be bought overseas. But her argument relies on measuring the proposed emissions cuts against the big increase in Australian emissions that would occur by 2020 if industry carried on business as usual.

The unlimited purchasing of emissions cuts overseas deeply concerns some environmentalists who believe that rich countries should make most of their own emissions cuts at home. Without domestic cuts, they argue, these countries have little incentive to switch to cleaner fuels from heavily polluting coal-fired power. “You have got to walk the talk,” says Paul Toni of WWF. “We can’t credibly go overseas and say that we will reduce emissions but in fact we outsource the whole lot to other countries when you are talking about such fundamental issues as energy infrastructure.”

Power Games

In Australia, coal-fired power generators are expected to stay in business well beyond 2020. But the owners of the generators are arguing that they will be penalized under the emissions trading scheme and are lobbying hard for more assistance above the AU$3.5 billion offered by the government. Leading the argument are the foreign owners of the power generators in Victoria, the country’s most urbanized state, and they are exerting enormous political pressure on the state government to get concessions. CLP Holdings, formerly China Light and Power, is chaired by Hong Kong’s fourth wealthiest man, billionaire Sir Michael Kadoorie. The company’s Australian arm, TRUenergy, operates a coal plant in Victoria that has been one of the most heavily polluting power stations in Australia, according to emissions analyst Dr. Hugh Saddler. The chief executive of TRUenergy in Australia, Richard McIndoe, kicked off his campaign by writing to Victorian Labor Premier John Brumby and Prime Minister Rudd, warning of “supply failures” if the power companies were not given more assistance under the emissions trading scheme.

Last summer, after Victoria experienced its worst heatwave in history, the generators’ demands took on more prominence and packed far more political punch. One of the state’s main electricity networks was forced to shut down as temperatures soared, surpassing 46 C or 115 F in Melbourne and reducing power supplies. Rail lines buckled in the heat, disrupting commuters, and hospitals recorded 374 additional deaths. Within days of the heatwave, the devastating “Black Saturday” bushfires engulfed large areas of the state, killing 173 people. After the horrific summer, any threat to the state’s power supply became difficult for the state’s politicians to ignore.

The federal government’s current offer to the generators is in the form of AU$3.5 billion in free permits for the first five years of the emissions trading scheme. The bulk of the assistance would go to the foreign-owned generators, including Kadoorie’s company. The giant U.K.-based company International Power was expected to get around AU$1.15 billion. International Power’s coal plant in Victoria, Hazelwood, holds the dubious honor of being the biggest greenhouse gas-emitting generator in Australia. But in February, International Power’s Australian chief, Tony Concannon, dismissed the government’s offer to the industry as completely inadequate, asking Rudd for triple the amount of assistance. He also later suggested Hazelwood could be bought out by the government.

One of the power generators’ complaints is that the value of their more polluting brown coal generators will drop under the emissions trading scheme. A loss of value combined with their already high debt obligations, they argue, will make banks wary of refinancing them unless they get more free permits. Indeed, they contend that the current debt crisis could result in the closure of some generators.

In June, the industry trade lobby, the National Generators Forum, wrote to all members of Parliament painting a bleak picture of the “systemic failure of the electricity market” unless the generators got more compensation. Some generators would be left “technically insolvent,” the letter claimed. At the heart of the generators’ claim is a demand for AU$10 billion in government compensation, an argument that has won support from the opposition party.

Neither Concannon nor McIndoe agreed to be interviewed for this article, but they have both briefed financial reporters on the threat of power shortages. The threat was also repeatedly raised with Victoria’s energy minister, Peter Batchelor. One power industry figure described the pressure on Batchelor as being “of the steamroller type.”

Prime Minister Rudd has dismissed the notion of threats to energy security, relying on advice from the national energy regulator. But wide media coverage of the generators’ warning persuaded Rudd to set up a task force chaired by his most senior bureaucrat, Terry Moran, the head of the office of Prime Minister and Cabinet. The task force hired the investment banking firm Morgan Stanley to examine the financial records of several generators and report back on their claims of insolvency. The appointment delighted the generators. As one director put it, “The guys at Morgan Stanley who did that report have bought and sold more power stations in the country than anyone”. The Morgan Stanley review remains secret. But media leaks suggest it backs the power generators’ arguments for a rise in their compensation, despite Wong’s insistence that the generators’ compensation was “both appropriate and well-targeted”. Any additional compensation is likely to come from taxpayers.

Amid the alarming stories about the generators’ financial crisis, the companies’ profit reports for the first six months of the year went relatively unnoticed in the media. Earnings from CLP’s Australian coal-fired generators were up 77 percent, jumping to AU$29 million, while International Power’s Australian profits jumped 71 percent to AU$212 million.

The Coal War

Just as the power generators’ campaign climaxed in August, executives from the world’s largest coal companies held a strategy meeting behind closed doors. Australia is the world’s largest coal exporter, a trade valued at AU$55 billion last year. After weeks of debate, the executives representing the United States’ Peabody Energy, British-South African giant Anglo-American, Swiss-based Xstrata, Australian-British BHP-Billiton, British-Australian Rio Tinto, and other companies unanimously agreed to fund a multi-million-dollar attack on the government’s proposed treatment of coal under the emissions trading scheme.

Under the banner “Let’s cut emissions, not jobs,” the Australian Coal Association is churning out big coal’s message on local television, radio, and in newspapers. It warns workers that the emissions trading scheme will close mines and “cut thousands of jobs,” slashing property values and causing families to abandon coal towns. A website directs workers to e-mail their local member of parliament to protest against the scheme.

The campaign is running in coal-mining towns in Queensland and New South Wales, both dominated by MPs from the left-of-center Labor Party. Ralph Hillman, head of the Australian Coal Association, denies that the industry is deliberately targeting Labor’s marginal seats. “It so happens one of my advisors noted that half of the seats may be marginal, but we are not targeting marginal seats. We are not targeting Labor seats”.

The industry used two of Australia’s top political strategists to advise on the campaign: Neil Lawrence, who worked on Rudd’s successful election in 2007, and Linton Crosby, a veteran of past Liberal Party victories. The team also includes Tim Duncan, the one-time head of Rio Tinto’s media unit, and Paul White, who worked for stevedore company owner Chris Corrigan during a bitter labor dispute with the waterside workers union a decade ago. Wong’s assistant minister, Greg Combet, a former trade union leader, helped run the workers’ campaign against Corrigan and is so far not convinced by the industry case. The coal executives say Combet is not listening.

The coal executives’ complaint is with the government plan to include methane released by coal mining in the proposed trading scheme. Methane is one of the most potent greenhouse gases, and it makes up a significant five percent of Australia’s total emissions. Under the emissions trading scheme, the owners of methane-emitting — or “gassy” — mines will be forced to buy permits for these emissions if they want to continue mining.

The government has promised the coal industry AU$750 million in compensation for the most gassy mines. But Combet, an engineer and an economist by training, says most coal companies won’t be significantly affected by the proposed legislation and can afford to buy their permits. Half the industry, he says, will pay 80 cents or less per metric ton of coal for their emissions. “Given that coal is currently selling for between around AU$70 and AU$150 per metric ton in exports markets, it is simply misleading to suggest, as some have done, that carbon costs of this magnitude will lead to decisions to close mines,” says Combet.

But Hillman rejects that argument, saying that one company told him it will be forced to pay up to $7 per metric ton. The coal companies want the same level of free permits granted to the gas industry, which under the plan would get about 65 percent of their emissions covered.

Australia’s leading environmental groups are warning Rudd that they will withdraw their support for the emissions trading scheme if the coal industry and the power generators get any more compensation. “It’s not effective or responsible to give windfall gains to booming coal miners or to give billions extra to businesses who bought brown coal-fired generators knowing a carbon price was coming,” says the Climate Institute’s John Connor.

Connor underscores the arguments that government ministers were making just a few weeks ago. If companies keep avoiding actions that shift Australia away from its heavily polluting ways, he says, the nation will face a much higher cost of doing so in the future.

The problem is that many of chief executives from the biggest polluting companies appear to be more focused on the bottom line. It leaves politicians like Wong a tough choice: either accept their arguments and give more compensation, or persuade her political opponents that the government’s proposal is the best outcome business is likely to get as pressure mounts globally to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

“It is important for all of us to remember this: The chance for us to avoid any climate change at all is gone, it is lost to us,” Wong told senators in August “What we do have is a window to lessen its impact. We have a window to reduce the risk, and this is a window of opportunity which is closing.”

Marian Wilkinson is environment editor of the Sydney Morning Herald. Ben Cubby is the Herald‘s environment reporter. Flint Duxfield is a free-lance journalist and an intern at the Herald.